Imagine a city ablaze, not from invading armies, but from its own furious heartbeat. Chants echoing through marble halls, turning sport into sedition, and a single woman's words tipping the scales between empire's fall and its fiery rebirth. This isn't the plot of a blockbuster epic—it's the raw, riveting reality of the Nika Riots that ignited on January 13, 532 AD, in the heart of Constantinople, the glittering jewel of the Byzantine Empire. On that fateful day, what began as a routine chariot race spiraled into one of history's most explosive urban upheavals, nearly toppling Emperor Justinian I and reshaping the course of an empire. But from the ashes of this chaos emerged lessons in resilience, strategy, and unyielding spirit that echo across centuries. Dive with me into this whirlwind of history, where we'll unpack the intricate web of politics, passion, and power plays that defined the event. Then, we'll bridge the gap to today, showing how you can harness that ancient grit to conquer your own modern battles—because history isn't just dates and dust; it's a blueprint for boldness.

Let's set the stage properly, because to grasp the Nika Riots, you need to understand the Byzantine world of the 6th century. The Byzantine Empire, often called the Eastern Roman Empire, was the enduring remnant of Rome's glory after the Western half crumbled under barbarian invasions in 476 AD. Centered in Constantinople—founded by Constantine the Great in 330 AD on the ancient site of Byzantium—this empire blended Roman law, Greek culture, and Christian faith into a powerhouse that dominated the Mediterranean for over a millennium. By 532, it was ruled by Justinian I, a man whose ambitions burned as brightly as the fires that would soon engulf his capital.

Justinian, born Flavius Petrus Sabbatius around 482 AD in a modest village in what is now North Macedonia, rose improbably to the throne. His uncle, Justin, a illiterate soldier from the same rural roots, had climbed the military ranks to become emperor in 518 AD after the death of Anastasius I. Justin adopted Justinian, educating him in Constantinople and grooming him as successor. When Justin died in 527, Justinian ascended, bringing with him a vision of *renovatio imperii*—the restoration of the Roman Empire's lost territories. He dreamed of reconquering the West, from North Africa to Italy, and unifying the realm under a single legal code and Christian doctrine. But dreams come at a cost, and Justinian's policies sowed seeds of discontent that would erupt on January 13.

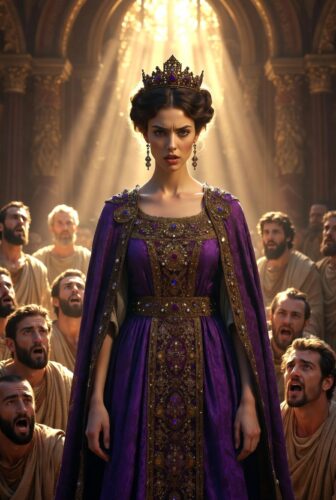

Central to Byzantine society were the demes—factions originally tied to chariot racing in the Hippodrome, a massive U-shaped stadium that could seat up to 80,000 spectators. These weren't mere fan clubs; they were powerful social and political entities. By the 6th century, the four original colors—Blues (Veneti), Greens (Prasini), Reds (Russati), and Whites (Albati)—had consolidated into two dominant rivals: the Blues and the Greens. The Blues often represented the aristocracy, orthodox Christians, and landowners, while the Greens drew support from merchants, tradespeople, and those with Monophysite leanings (a Christian sect emphasizing Christ's divine nature over his human one, at odds with the official Chalcedonian creed). Emperors like Justinian used these factions to gauge public opinion, rally support, or even suppress dissent. Justinian himself had initially favored the Blues, perhaps due to his wife Theodora's early connections with them, but by 532, he sought to curb their influence, enacting laws against their violent excesses. Theodora, Justinian's empress, is a figure who leaps from the pages of history like a force of nature. Born around 500 AD into poverty, her father Acacius was a bear trainer for the Greens at the Hippodrome, and her mother an actress and dancer. After Acacius's death when Theodora was about four, her family faced destitution. Legend has it that her mother paraded the three daughters—Comito, Theodora, and Anastasia—before the crowd, begging for patronage. The Greens turned them away, but the Blues took them in, shaping Theodora's lifelong allegiance. As a young woman, Theodora worked as an actress, a profession synonymous with scandal in Byzantine eyes—often involving risqué performances and associations with prostitution. Contemporary historian Procopius, in his scathing *Secret History*, painted her as a courtesan of insatiable appetites, recounting salacious tales of her stage acts, including one where geese pecked barley from her body in a mimicry of Leda and the Swan. While Procopius's work is laced with bias (he despised Justinian's regime), it underscores the elite's disdain for Theodora's lowborn origins.

Theodora's path crossed Justinian's around 522, when she returned to Constantinople after travels that took her to Alexandria and Antioch, possibly deepening her sympathy for Monophysite Christians. Justinian, then heir apparent, fell deeply in love, but Roman law forbade senators from marrying actresses. He petitioned his uncle to change the law, and in 525, they wed. When Justinian became emperor, Theodora was crowned Augusta, becoming his equal in influence if not title. She wasn't just a consort; she attended councils, advised on policy, and wielded power ruthlessly. Her intelligence, forged in hardship, made her a formidable ally—and a dangerous enemy.

Tensions simmered in Constantinople by late 531. Justinian's wars against the Sassanid Persians had drained the treasury; a defeat at Callinicum in 531 stung his pride. At home, his quaestor Tribonian and praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian enforced harsh taxes to fund ambitions, alienating the aristocracy and common folk alike. Corruption scandals swirled, with John accused of extortion and brutality. The demes, meanwhile, had grown bolder under Justin's lax rule, engaging in street brawls, murders, and vandalism. Justinian's 527 decree banning stone-throwing and weapons at races aimed to rein them in, but enforcement was spotty.

Theodora, Justinian's empress, is a figure who leaps from the pages of history like a force of nature. Born around 500 AD into poverty, her father Acacius was a bear trainer for the Greens at the Hippodrome, and her mother an actress and dancer. After Acacius's death when Theodora was about four, her family faced destitution. Legend has it that her mother paraded the three daughters—Comito, Theodora, and Anastasia—before the crowd, begging for patronage. The Greens turned them away, but the Blues took them in, shaping Theodora's lifelong allegiance. As a young woman, Theodora worked as an actress, a profession synonymous with scandal in Byzantine eyes—often involving risqué performances and associations with prostitution. Contemporary historian Procopius, in his scathing *Secret History*, painted her as a courtesan of insatiable appetites, recounting salacious tales of her stage acts, including one where geese pecked barley from her body in a mimicry of Leda and the Swan. While Procopius's work is laced with bias (he despised Justinian's regime), it underscores the elite's disdain for Theodora's lowborn origins.

Theodora's path crossed Justinian's around 522, when she returned to Constantinople after travels that took her to Alexandria and Antioch, possibly deepening her sympathy for Monophysite Christians. Justinian, then heir apparent, fell deeply in love, but Roman law forbade senators from marrying actresses. He petitioned his uncle to change the law, and in 525, they wed. When Justinian became emperor, Theodora was crowned Augusta, becoming his equal in influence if not title. She wasn't just a consort; she attended councils, advised on policy, and wielded power ruthlessly. Her intelligence, forged in hardship, made her a formidable ally—and a dangerous enemy.

Tensions simmered in Constantinople by late 531. Justinian's wars against the Sassanid Persians had drained the treasury; a defeat at Callinicum in 531 stung his pride. At home, his quaestor Tribonian and praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian enforced harsh taxes to fund ambitions, alienating the aristocracy and common folk alike. Corruption scandals swirled, with John accused of extortion and brutality. The demes, meanwhile, had grown bolder under Justin's lax rule, engaging in street brawls, murders, and vandalism. Justinian's 527 decree banning stone-throwing and weapons at races aimed to rein them in, but enforcement was spotty. The spark came on January 10, 532. After a race riot, city prefect Eudaemon arrested several Blues and Greens for murder. Seven were sentenced to hang, but the scaffold malfunctioned twice: five died, but one Blue and one Green survived, dangling until cut down. The crowd saw it as divine intervention and demanded pardon. The survivors sought sanctuary in the church of St. Lawrence, guarded by soldiers. Faction leaders petitioned Justinian, but he ignored them, preoccupied with Persian peace negotiations.

On January 13, 532—the Ides of January in the Roman calendar—the powder keg exploded. The Hippodrome races commenced, with Justinian presiding from the kathisma, his imperial box connected to the palace. The crowd, a mix of Blues and Greens, began with typical chants supporting their colors. But frustration boiled over. By the 22nd race, the chants unified: instead of "Blue!" or "Green!", they shouted "Nika!"—Greek for "Conquer!" or "Victory!"—a rallying cry from the races now turned against the emperor. The mob surged, assaulting the praetorium (prefect's headquarters) and freeing prisoners. Fires broke out, consuming the Chalke Gate (the palace's bronze entrance), parts of the Senate house, and the original Hagia Sophia cathedral, a wooden-roofed basilica built by Theodosius II.

The riots weren't spontaneous anarchy; they had organization. Faction members, armed like militias, coordinated attacks. Senators, sensing opportunity, fueled the flames, hoping to depose Justinian, whom they viewed as a lowborn upstart. By nightfall on January 13, the city was in pandemonium. Flames lit the sky, and chants of "Nika!" reverberated through the streets. Justinian's guards clashed with rioters, but the imperial response was hesitant. The emperor, advised by his council, considered concessions but underestimated the threat.

January 14 brought escalation. Rioters demanded the dismissal of John the Cappadocian, Tribonian, and Eudaemon, blaming them for injustices. Justinian complied, appointing new officials, but it was too late. The mob, now a unified force, proclaimed Hypatius—nephew of the late Emperor Anastasius I—as emperor. Hypatius, a senator with imperial blood, was dragged from his home against his will (according to Procopius) and crowned with a golden necklace in the Forum of Constantine. Crowds paraded him to the Hippodrome, where he assumed the kathisma.

Inside the palace, panic reigned. Justinian prepared to flee by sea, loading ships with treasures. His generals, including the famed Belisarius (fresh from Persian campaigns) and Mundus (a Gepid commander), urged action, but the emperor wavered. It was here, in this council of desperation, that Theodora delivered her immortal speech. As recounted by Procopius in *Wars of Justinian*: "My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud."

Her words—evoking dignity over dishonor, empire over exile—galvanized Justinian. He resolved to fight. Narses, a trusted eunuch chamberlain, was dispatched unarmed to the Hippodrome with bags of gold. Approaching the Blues' section, he reminded them of Justinian's past favoritism and Theodora's loyalty to their faction, sowing division. The Blues wavered, then turned on the Greens, sparking internal clashes.

Seizing the moment, Belisarius led imperial excubitors (elite guards) and bucellarii (private troops) from the palace, but the main gate was barred. He circled to the northern entrance, known as the Gate of Death, and stormed in. Mundus entered from the west, and their forces converged on the 30,000-40,000 trapped rioters. What followed was a massacre: swords and spears cut down men, women, and children indiscriminately. Procopius estimates 30,000 dead, though some modern scholars suggest up to 35,000 or more, with bodies piled high and blood staining the sand.

The spark came on January 10, 532. After a race riot, city prefect Eudaemon arrested several Blues and Greens for murder. Seven were sentenced to hang, but the scaffold malfunctioned twice: five died, but one Blue and one Green survived, dangling until cut down. The crowd saw it as divine intervention and demanded pardon. The survivors sought sanctuary in the church of St. Lawrence, guarded by soldiers. Faction leaders petitioned Justinian, but he ignored them, preoccupied with Persian peace negotiations.

On January 13, 532—the Ides of January in the Roman calendar—the powder keg exploded. The Hippodrome races commenced, with Justinian presiding from the kathisma, his imperial box connected to the palace. The crowd, a mix of Blues and Greens, began with typical chants supporting their colors. But frustration boiled over. By the 22nd race, the chants unified: instead of "Blue!" or "Green!", they shouted "Nika!"—Greek for "Conquer!" or "Victory!"—a rallying cry from the races now turned against the emperor. The mob surged, assaulting the praetorium (prefect's headquarters) and freeing prisoners. Fires broke out, consuming the Chalke Gate (the palace's bronze entrance), parts of the Senate house, and the original Hagia Sophia cathedral, a wooden-roofed basilica built by Theodosius II.

The riots weren't spontaneous anarchy; they had organization. Faction members, armed like militias, coordinated attacks. Senators, sensing opportunity, fueled the flames, hoping to depose Justinian, whom they viewed as a lowborn upstart. By nightfall on January 13, the city was in pandemonium. Flames lit the sky, and chants of "Nika!" reverberated through the streets. Justinian's guards clashed with rioters, but the imperial response was hesitant. The emperor, advised by his council, considered concessions but underestimated the threat.

January 14 brought escalation. Rioters demanded the dismissal of John the Cappadocian, Tribonian, and Eudaemon, blaming them for injustices. Justinian complied, appointing new officials, but it was too late. The mob, now a unified force, proclaimed Hypatius—nephew of the late Emperor Anastasius I—as emperor. Hypatius, a senator with imperial blood, was dragged from his home against his will (according to Procopius) and crowned with a golden necklace in the Forum of Constantine. Crowds paraded him to the Hippodrome, where he assumed the kathisma.

Inside the palace, panic reigned. Justinian prepared to flee by sea, loading ships with treasures. His generals, including the famed Belisarius (fresh from Persian campaigns) and Mundus (a Gepid commander), urged action, but the emperor wavered. It was here, in this council of desperation, that Theodora delivered her immortal speech. As recounted by Procopius in *Wars of Justinian*: "My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud."

Her words—evoking dignity over dishonor, empire over exile—galvanized Justinian. He resolved to fight. Narses, a trusted eunuch chamberlain, was dispatched unarmed to the Hippodrome with bags of gold. Approaching the Blues' section, he reminded them of Justinian's past favoritism and Theodora's loyalty to their faction, sowing division. The Blues wavered, then turned on the Greens, sparking internal clashes.

Seizing the moment, Belisarius led imperial excubitors (elite guards) and bucellarii (private troops) from the palace, but the main gate was barred. He circled to the northern entrance, known as the Gate of Death, and stormed in. Mundus entered from the west, and their forces converged on the 30,000-40,000 trapped rioters. What followed was a massacre: swords and spears cut down men, women, and children indiscriminately. Procopius estimates 30,000 dead, though some modern scholars suggest up to 35,000 or more, with bodies piled high and blood staining the sand. By January 19, the riots were crushed. Hypatius and his brother Pompeius (a former consul) were captured, protesting innocence—Hypatius claimed he acted under duress. Justinian, influenced by Theodora's reported insistence on no mercy, had them executed the next day, their bodies thrown into the sea. Senators suspected of collusion were exiled, their properties confiscated, though some were later pardoned. The city smoldered: nearly half of Constantinople lay in ruins, including the Hagia Sophia, the Baths of Zeuxippus, the Hospice of Samson, and countless homes and churches. The human toll was staggering, with families shattered and the demes decimated.

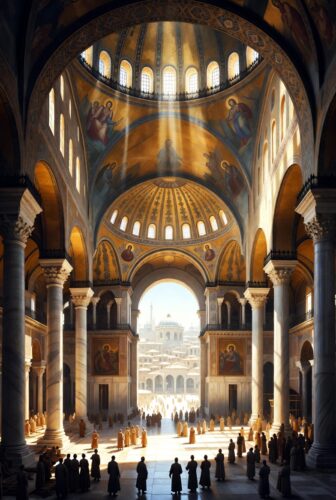

In the aftermath, Justinian turned destruction into opportunity. He rebuilt Constantinople on a grander scale, commissioning the new Hagia Sophia—a architectural marvel with its massive dome, designed by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. Completed in just five years (532-537), it cost 20,000 pounds of gold and symbolized divine favor, its interior gleaming with mosaics and marble. Other projects included fortified walls, aqueducts, and the Basilica Cistern. The riots also purged opposition, allowing Justinian to reinstate John the Cappadocian and Tribonian, accelerating his legal reforms.

The *Corpus Juris Civilis*, begun in 528, culminated in 534 with the Code, Digest, and Institutes— a monumental codification of Roman law that abolished outdated statutes, harmonized contradictions, and influenced legal systems for centuries, from medieval Europe to modern civil codes. Justinian's wars flourished post-riots: Belisarius reconquered Vandal Africa in 533-534, then Ostrogothic Italy in 535-554, though plagues and overextension plagued the empire. The 541-542 Plague of Justinian, possibly bubonic, killed millions, including nearly a third of Constantinople's population, but the emperor survived.

Theodora's role extended beyond the riots. She championed women's rights, enacting laws against forced prostitution, allowing actresses to marry freely, and protecting divorcees' dowries. Her Monophysite sympathies balanced Justinian's Chalcedonian policies, fostering religious tolerance in a divided empire. She died in 548, likely of cancer, leaving Justinian bereft; he never remarried and honored her memory in laws and buildings.

By January 19, the riots were crushed. Hypatius and his brother Pompeius (a former consul) were captured, protesting innocence—Hypatius claimed he acted under duress. Justinian, influenced by Theodora's reported insistence on no mercy, had them executed the next day, their bodies thrown into the sea. Senators suspected of collusion were exiled, their properties confiscated, though some were later pardoned. The city smoldered: nearly half of Constantinople lay in ruins, including the Hagia Sophia, the Baths of Zeuxippus, the Hospice of Samson, and countless homes and churches. The human toll was staggering, with families shattered and the demes decimated.

In the aftermath, Justinian turned destruction into opportunity. He rebuilt Constantinople on a grander scale, commissioning the new Hagia Sophia—a architectural marvel with its massive dome, designed by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. Completed in just five years (532-537), it cost 20,000 pounds of gold and symbolized divine favor, its interior gleaming with mosaics and marble. Other projects included fortified walls, aqueducts, and the Basilica Cistern. The riots also purged opposition, allowing Justinian to reinstate John the Cappadocian and Tribonian, accelerating his legal reforms.

The *Corpus Juris Civilis*, begun in 528, culminated in 534 with the Code, Digest, and Institutes— a monumental codification of Roman law that abolished outdated statutes, harmonized contradictions, and influenced legal systems for centuries, from medieval Europe to modern civil codes. Justinian's wars flourished post-riots: Belisarius reconquered Vandal Africa in 533-534, then Ostrogothic Italy in 535-554, though plagues and overextension plagued the empire. The 541-542 Plague of Justinian, possibly bubonic, killed millions, including nearly a third of Constantinople's population, but the emperor survived.

Theodora's role extended beyond the riots. She championed women's rights, enacting laws against forced prostitution, allowing actresses to marry freely, and protecting divorcees' dowries. Her Monophysite sympathies balanced Justinian's Chalcedonian policies, fostering religious tolerance in a divided empire. She died in 548, likely of cancer, leaving Justinian bereft; he never remarried and honored her memory in laws and buildings. The Nika Riots' significance can't be overstated. They marked the bloodiest urban revolt in Byzantine history, highlighting the volatile mix of sport, politics, and social grievance. Faction unity was rare; their militarization turned a protest into a near-coup. Historians debate causes: was it senatorial conspiracy? Justinian's provocation to expose enemies? Or genuine outrage over taxes and justice? Procopius's accounts—praising in *Wars*, vilifying in *Secret History*—offer dual lenses, but the event underscored imperial fragility. It also showcased women's agency: Theodora's speech, whether verbatim or embellished, immortalized her as a symbol of resolve.

Fires faded, but the riots reshaped Byzantium. Justinian's reign peaked, with territories stretching from Spain to Syria, but strains foreshadowed decline. The demes persisted but under tighter control; future emperors like Maurice and Heraclius faced similar unrest. In broader history, the Nika episode illustrates how internal divisions can threaten even mighty states, a cautionary tale echoed in later revolts like the French Revolution or modern uprisings.

Shifting from the smoke-filled streets of 532 to your life in 2026, the Nika Riots offer more than trivia—they're a masterclass in turning crisis into catalyst. At its core, this event teaches unyielding resolve: Justinian and Theodora didn't flee; they faced the storm, divided their foes, and rebuilt stronger. In today's world of economic uncertainties, personal setbacks, and relentless change, channeling that Byzantine backbone can transform obstacles into opportunities. Imagine applying Theodora's "royalty is a good burial-shroud" mindset—not literally, but as a metaphor for standing firm in your principles, refusing to abandon your "throne" whether it's a career goal, relationship, or self-improvement quest. The benefit? Greater confidence, faster recovery from failures, and a life built on intentional victories rather than reactive retreats.

Here's how this historical grit translates to your daily grind, with specific ways it benefits you individually:

- **Boosted Decision-Making Under Pressure**: In the riots, Justinian's hesitation nearly cost everything, but Theodora's clarity saved the day. Today, when facing a high-stakes choice—like negotiating a salary raise or confronting a toxic colleague—emulate her by pausing to affirm your core values. Benefit: You'll make choices aligned with long-term success, reducing regret and building mental toughness, leading to promotions or healthier work environments.

- **Enhanced Relationship Resilience**: The Blues' defection via Narses's persuasion shows how dividing opposition works. In personal ties, if dealing with family conflicts or partnership strains, identify shared interests to bridge divides. For instance, during a heated argument with a spouse over finances, highlight mutual goals like family security instead of escalating. Benefit: Stronger bonds, less isolation, and emotional stability, fostering deeper connections that support your well-being and happiness.

- **Improved Goal Achievement Through Rebuilding**: Post-riots, Justinian reconstructed Hagia Sophia grander than before. After a setback, like a failed business venture or fitness plateau, assess the "ruins" and rebuild bigger—revise your plan with lessons learned. Benefit: Accelerated progress toward ambitions, turning losses into launches, resulting in achievements like landing a dream job or hitting personal milestones faster.

- **Greater Financial Savvy from Resource Management**: Justinian's taxes fueled riots, but his post-crisis reforms stabilized the empire. Apply this by auditing your budget during tough times, cutting waste while investing in growth areas. For example, if inflation bites, redirect funds from impulse buys to skill-building courses. Benefit: Financial security, reduced stress, and freedom to pursue passions, leading to a more fulfilled, independent life.

- **Heightened Self-Awareness and Empathy**: Theodora's humble origins informed her empathy for the marginalized, influencing policies. Reflect on your background to fuel compassion in interactions, like mentoring a junior colleague or volunteering. Benefit: Richer social networks, personal growth, and a sense of purpose that combats loneliness and boosts overall life satisfaction.

The Nika Riots' significance can't be overstated. They marked the bloodiest urban revolt in Byzantine history, highlighting the volatile mix of sport, politics, and social grievance. Faction unity was rare; their militarization turned a protest into a near-coup. Historians debate causes: was it senatorial conspiracy? Justinian's provocation to expose enemies? Or genuine outrage over taxes and justice? Procopius's accounts—praising in *Wars*, vilifying in *Secret History*—offer dual lenses, but the event underscored imperial fragility. It also showcased women's agency: Theodora's speech, whether verbatim or embellished, immortalized her as a symbol of resolve.

Fires faded, but the riots reshaped Byzantium. Justinian's reign peaked, with territories stretching from Spain to Syria, but strains foreshadowed decline. The demes persisted but under tighter control; future emperors like Maurice and Heraclius faced similar unrest. In broader history, the Nika episode illustrates how internal divisions can threaten even mighty states, a cautionary tale echoed in later revolts like the French Revolution or modern uprisings.

Shifting from the smoke-filled streets of 532 to your life in 2026, the Nika Riots offer more than trivia—they're a masterclass in turning crisis into catalyst. At its core, this event teaches unyielding resolve: Justinian and Theodora didn't flee; they faced the storm, divided their foes, and rebuilt stronger. In today's world of economic uncertainties, personal setbacks, and relentless change, channeling that Byzantine backbone can transform obstacles into opportunities. Imagine applying Theodora's "royalty is a good burial-shroud" mindset—not literally, but as a metaphor for standing firm in your principles, refusing to abandon your "throne" whether it's a career goal, relationship, or self-improvement quest. The benefit? Greater confidence, faster recovery from failures, and a life built on intentional victories rather than reactive retreats.

Here's how this historical grit translates to your daily grind, with specific ways it benefits you individually:

- **Boosted Decision-Making Under Pressure**: In the riots, Justinian's hesitation nearly cost everything, but Theodora's clarity saved the day. Today, when facing a high-stakes choice—like negotiating a salary raise or confronting a toxic colleague—emulate her by pausing to affirm your core values. Benefit: You'll make choices aligned with long-term success, reducing regret and building mental toughness, leading to promotions or healthier work environments.

- **Enhanced Relationship Resilience**: The Blues' defection via Narses's persuasion shows how dividing opposition works. In personal ties, if dealing with family conflicts or partnership strains, identify shared interests to bridge divides. For instance, during a heated argument with a spouse over finances, highlight mutual goals like family security instead of escalating. Benefit: Stronger bonds, less isolation, and emotional stability, fostering deeper connections that support your well-being and happiness.

- **Improved Goal Achievement Through Rebuilding**: Post-riots, Justinian reconstructed Hagia Sophia grander than before. After a setback, like a failed business venture or fitness plateau, assess the "ruins" and rebuild bigger—revise your plan with lessons learned. Benefit: Accelerated progress toward ambitions, turning losses into launches, resulting in achievements like landing a dream job or hitting personal milestones faster.

- **Greater Financial Savvy from Resource Management**: Justinian's taxes fueled riots, but his post-crisis reforms stabilized the empire. Apply this by auditing your budget during tough times, cutting waste while investing in growth areas. For example, if inflation bites, redirect funds from impulse buys to skill-building courses. Benefit: Financial security, reduced stress, and freedom to pursue passions, leading to a more fulfilled, independent life.

- **Heightened Self-Awareness and Empathy**: Theodora's humble origins informed her empathy for the marginalized, influencing policies. Reflect on your background to fuel compassion in interactions, like mentoring a junior colleague or volunteering. Benefit: Richer social networks, personal growth, and a sense of purpose that combats loneliness and boosts overall life satisfaction. To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Nika-inspired resolve into your life over the next 30 days. Think of it as your personal "renovatio"—a restoration of your inner empire:

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Nika-inspired resolve into your life over the next 30 days. Think of it as your personal "renovatio"—a restoration of your inner empire:

**Day 1-3: Assess Your Battlefield**: Journal about current challenges, mirroring the riots' causes. List "factions" in your life—conflicting priorities like work vs. family—and identify unifying "Nika" moments where they erupt. Goal: Gain clarity, preventing small issues from becoming revolts.

**Day 4-10: Channel Theodora's Speech**: Craft a personal mantra, like "I won't flee my throne; resolve is my shroud." Recite it during stress, such as before a tough meeting. Practice by role-playing scenarios, building confidence to stand firm.

**Day 11-20: Divide and Conquer**: Tackle one challenge by breaking it down. For career stagnation, "bribe" your doubts with small wins—update your resume, network on LinkedIn. Track progress to see divisions weaken.

**Day 21-25: Suppress and Secure**: Act decisively on a key issue, like ending a draining habit. Use tools like apps for habit-tracking to "massacre" procrastination, securing your "palace" of productivity.

**Day 26-30: Rebuild Grandly**: Invest in growth—enroll in a course, plan a trip, or renovate a skill. Celebrate with a "Hagia Sophia" moment: something symbolic of your triumph, like treating yourself to a meaningful purchase.

By weaving these threads from 532 into your tapestry, you'll not only honor history but ignite your potential. The Nika Riots remind us that from the brink of collapse comes the chance for conquest. So, stand tall—your empire awaits.

Theodora, Justinian's empress, is a figure who leaps from the pages of history like a force of nature. Born around 500 AD into poverty, her father Acacius was a bear trainer for the Greens at the Hippodrome, and her mother an actress and dancer. After Acacius's death when Theodora was about four, her family faced destitution. Legend has it that her mother paraded the three daughters—Comito, Theodora, and Anastasia—before the crowd, begging for patronage. The Greens turned them away, but the Blues took them in, shaping Theodora's lifelong allegiance. As a young woman, Theodora worked as an actress, a profession synonymous with scandal in Byzantine eyes—often involving risqué performances and associations with prostitution. Contemporary historian Procopius, in his scathing *Secret History*, painted her as a courtesan of insatiable appetites, recounting salacious tales of her stage acts, including one where geese pecked barley from her body in a mimicry of Leda and the Swan. While Procopius's work is laced with bias (he despised Justinian's regime), it underscores the elite's disdain for Theodora's lowborn origins. Theodora's path crossed Justinian's around 522, when she returned to Constantinople after travels that took her to Alexandria and Antioch, possibly deepening her sympathy for Monophysite Christians. Justinian, then heir apparent, fell deeply in love, but Roman law forbade senators from marrying actresses. He petitioned his uncle to change the law, and in 525, they wed. When Justinian became emperor, Theodora was crowned Augusta, becoming his equal in influence if not title. She wasn't just a consort; she attended councils, advised on policy, and wielded power ruthlessly. Her intelligence, forged in hardship, made her a formidable ally—and a dangerous enemy. Tensions simmered in Constantinople by late 531. Justinian's wars against the Sassanid Persians had drained the treasury; a defeat at Callinicum in 531 stung his pride. At home, his quaestor Tribonian and praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian enforced harsh taxes to fund ambitions, alienating the aristocracy and common folk alike. Corruption scandals swirled, with John accused of extortion and brutality. The demes, meanwhile, had grown bolder under Justin's lax rule, engaging in street brawls, murders, and vandalism. Justinian's 527 decree banning stone-throwing and weapons at races aimed to rein them in, but enforcement was spotty.

The spark came on January 10, 532. After a race riot, city prefect Eudaemon arrested several Blues and Greens for murder. Seven were sentenced to hang, but the scaffold malfunctioned twice: five died, but one Blue and one Green survived, dangling until cut down. The crowd saw it as divine intervention and demanded pardon. The survivors sought sanctuary in the church of St. Lawrence, guarded by soldiers. Faction leaders petitioned Justinian, but he ignored them, preoccupied with Persian peace negotiations. On January 13, 532—the Ides of January in the Roman calendar—the powder keg exploded. The Hippodrome races commenced, with Justinian presiding from the kathisma, his imperial box connected to the palace. The crowd, a mix of Blues and Greens, began with typical chants supporting their colors. But frustration boiled over. By the 22nd race, the chants unified: instead of "Blue!" or "Green!", they shouted "Nika!"—Greek for "Conquer!" or "Victory!"—a rallying cry from the races now turned against the emperor. The mob surged, assaulting the praetorium (prefect's headquarters) and freeing prisoners. Fires broke out, consuming the Chalke Gate (the palace's bronze entrance), parts of the Senate house, and the original Hagia Sophia cathedral, a wooden-roofed basilica built by Theodosius II. The riots weren't spontaneous anarchy; they had organization. Faction members, armed like militias, coordinated attacks. Senators, sensing opportunity, fueled the flames, hoping to depose Justinian, whom they viewed as a lowborn upstart. By nightfall on January 13, the city was in pandemonium. Flames lit the sky, and chants of "Nika!" reverberated through the streets. Justinian's guards clashed with rioters, but the imperial response was hesitant. The emperor, advised by his council, considered concessions but underestimated the threat. January 14 brought escalation. Rioters demanded the dismissal of John the Cappadocian, Tribonian, and Eudaemon, blaming them for injustices. Justinian complied, appointing new officials, but it was too late. The mob, now a unified force, proclaimed Hypatius—nephew of the late Emperor Anastasius I—as emperor. Hypatius, a senator with imperial blood, was dragged from his home against his will (according to Procopius) and crowned with a golden necklace in the Forum of Constantine. Crowds paraded him to the Hippodrome, where he assumed the kathisma. Inside the palace, panic reigned. Justinian prepared to flee by sea, loading ships with treasures. His generals, including the famed Belisarius (fresh from Persian campaigns) and Mundus (a Gepid commander), urged action, but the emperor wavered. It was here, in this council of desperation, that Theodora delivered her immortal speech. As recounted by Procopius in *Wars of Justinian*: "My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud." Her words—evoking dignity over dishonor, empire over exile—galvanized Justinian. He resolved to fight. Narses, a trusted eunuch chamberlain, was dispatched unarmed to the Hippodrome with bags of gold. Approaching the Blues' section, he reminded them of Justinian's past favoritism and Theodora's loyalty to their faction, sowing division. The Blues wavered, then turned on the Greens, sparking internal clashes. Seizing the moment, Belisarius led imperial excubitors (elite guards) and bucellarii (private troops) from the palace, but the main gate was barred. He circled to the northern entrance, known as the Gate of Death, and stormed in. Mundus entered from the west, and their forces converged on the 30,000-40,000 trapped rioters. What followed was a massacre: swords and spears cut down men, women, and children indiscriminately. Procopius estimates 30,000 dead, though some modern scholars suggest up to 35,000 or more, with bodies piled high and blood staining the sand.

By January 19, the riots were crushed. Hypatius and his brother Pompeius (a former consul) were captured, protesting innocence—Hypatius claimed he acted under duress. Justinian, influenced by Theodora's reported insistence on no mercy, had them executed the next day, their bodies thrown into the sea. Senators suspected of collusion were exiled, their properties confiscated, though some were later pardoned. The city smoldered: nearly half of Constantinople lay in ruins, including the Hagia Sophia, the Baths of Zeuxippus, the Hospice of Samson, and countless homes and churches. The human toll was staggering, with families shattered and the demes decimated. In the aftermath, Justinian turned destruction into opportunity. He rebuilt Constantinople on a grander scale, commissioning the new Hagia Sophia—a architectural marvel with its massive dome, designed by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. Completed in just five years (532-537), it cost 20,000 pounds of gold and symbolized divine favor, its interior gleaming with mosaics and marble. Other projects included fortified walls, aqueducts, and the Basilica Cistern. The riots also purged opposition, allowing Justinian to reinstate John the Cappadocian and Tribonian, accelerating his legal reforms. The *Corpus Juris Civilis*, begun in 528, culminated in 534 with the Code, Digest, and Institutes— a monumental codification of Roman law that abolished outdated statutes, harmonized contradictions, and influenced legal systems for centuries, from medieval Europe to modern civil codes. Justinian's wars flourished post-riots: Belisarius reconquered Vandal Africa in 533-534, then Ostrogothic Italy in 535-554, though plagues and overextension plagued the empire. The 541-542 Plague of Justinian, possibly bubonic, killed millions, including nearly a third of Constantinople's population, but the emperor survived. Theodora's role extended beyond the riots. She championed women's rights, enacting laws against forced prostitution, allowing actresses to marry freely, and protecting divorcees' dowries. Her Monophysite sympathies balanced Justinian's Chalcedonian policies, fostering religious tolerance in a divided empire. She died in 548, likely of cancer, leaving Justinian bereft; he never remarried and honored her memory in laws and buildings.

The Nika Riots' significance can't be overstated. They marked the bloodiest urban revolt in Byzantine history, highlighting the volatile mix of sport, politics, and social grievance. Faction unity was rare; their militarization turned a protest into a near-coup. Historians debate causes: was it senatorial conspiracy? Justinian's provocation to expose enemies? Or genuine outrage over taxes and justice? Procopius's accounts—praising in *Wars*, vilifying in *Secret History*—offer dual lenses, but the event underscored imperial fragility. It also showcased women's agency: Theodora's speech, whether verbatim or embellished, immortalized her as a symbol of resolve. Fires faded, but the riots reshaped Byzantium. Justinian's reign peaked, with territories stretching from Spain to Syria, but strains foreshadowed decline. The demes persisted but under tighter control; future emperors like Maurice and Heraclius faced similar unrest. In broader history, the Nika episode illustrates how internal divisions can threaten even mighty states, a cautionary tale echoed in later revolts like the French Revolution or modern uprisings. Shifting from the smoke-filled streets of 532 to your life in 2026, the Nika Riots offer more than trivia—they're a masterclass in turning crisis into catalyst. At its core, this event teaches unyielding resolve: Justinian and Theodora didn't flee; they faced the storm, divided their foes, and rebuilt stronger. In today's world of economic uncertainties, personal setbacks, and relentless change, channeling that Byzantine backbone can transform obstacles into opportunities. Imagine applying Theodora's "royalty is a good burial-shroud" mindset—not literally, but as a metaphor for standing firm in your principles, refusing to abandon your "throne" whether it's a career goal, relationship, or self-improvement quest. The benefit? Greater confidence, faster recovery from failures, and a life built on intentional victories rather than reactive retreats. Here's how this historical grit translates to your daily grind, with specific ways it benefits you individually: - **Boosted Decision-Making Under Pressure**: In the riots, Justinian's hesitation nearly cost everything, but Theodora's clarity saved the day. Today, when facing a high-stakes choice—like negotiating a salary raise or confronting a toxic colleague—emulate her by pausing to affirm your core values. Benefit: You'll make choices aligned with long-term success, reducing regret and building mental toughness, leading to promotions or healthier work environments. - **Enhanced Relationship Resilience**: The Blues' defection via Narses's persuasion shows how dividing opposition works. In personal ties, if dealing with family conflicts or partnership strains, identify shared interests to bridge divides. For instance, during a heated argument with a spouse over finances, highlight mutual goals like family security instead of escalating. Benefit: Stronger bonds, less isolation, and emotional stability, fostering deeper connections that support your well-being and happiness. - **Improved Goal Achievement Through Rebuilding**: Post-riots, Justinian reconstructed Hagia Sophia grander than before. After a setback, like a failed business venture or fitness plateau, assess the "ruins" and rebuild bigger—revise your plan with lessons learned. Benefit: Accelerated progress toward ambitions, turning losses into launches, resulting in achievements like landing a dream job or hitting personal milestones faster. - **Greater Financial Savvy from Resource Management**: Justinian's taxes fueled riots, but his post-crisis reforms stabilized the empire. Apply this by auditing your budget during tough times, cutting waste while investing in growth areas. For example, if inflation bites, redirect funds from impulse buys to skill-building courses. Benefit: Financial security, reduced stress, and freedom to pursue passions, leading to a more fulfilled, independent life. - **Heightened Self-Awareness and Empathy**: Theodora's humble origins informed her empathy for the marginalized, influencing policies. Reflect on your background to fuel compassion in interactions, like mentoring a junior colleague or volunteering. Benefit: Richer social networks, personal growth, and a sense of purpose that combats loneliness and boosts overall life satisfaction.

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Nika-inspired resolve into your life over the next 30 days. Think of it as your personal "renovatio"—a restoration of your inner empire: