The year is 947 AD, a time when the sands of North Africa were stained with the blood of ambition, faith, and power struggles. On August 19 of that year, in the rugged Hodna Mountains of what is now Algeria, a man known as the “Man on the Donkey” met his end. Abu Yazid Makhlad ibn Kaydad, a Berber rebel leader of the Ibadi Kharijite sect, died from wounds sustained in battle against the Fatimid Caliphate. This event marked the conclusion of one of the most dramatic uprisings in early Islamic history—a rebellion that nearly toppled a burgeoning empire and reshaped the political landscape of the Maghreb. While the death of Abu Yazid might seem like a distant echo from medieval chronicles, it offers profound insights into leadership, perseverance, and the human spirit’s capacity for defiance and recovery. In this blog, we’ll dive deep into the historical context, the key players, the battles, and the legacy of this event, before exploring how its outcomes can inspire and benefit your life today through practical, motivational applications.

### The Historical Backdrop: North Africa in the 10th Century

To understand the significance of August 19, 947, we must travel back to the turbulent world of the early Fatimid Caliphate. The Fatimids were an Ismaili Shia dynasty that emerged in the late 9th century, claiming descent from Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, and her husband Ali. Their rule was rooted in a messianic vision of restoring true Islamic leadership through hereditary imams. By 909 AD, the Fatimids, led by Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah, had overthrown the Aghlabid emirate in Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia and eastern Algeria) with the support of the Kutama Berbers, a fiercely loyal tribe converted to Ismailism. They established their capital at al-Mahdiyya, a fortified coastal city, and set their sights on expanding eastward to Egypt and beyond.

However, the Fatimids’ rule was far from secure. Their Shia doctrines alienated Sunni populations, and their heavy taxation and perceived favoritism toward the Kutama Berbers bred resentment among other tribes. Enter the Kharijites, a sect that originated in the 7th century during the First Fitna (civil war) after the death of the Prophet. The Kharijites believed in egalitarian leadership elected by merit, rejecting hereditary rule, and were known for their puritanical zeal and willingness to rebel against unjust authorities. The Ibadi branch, to which Abu Yazid belonged, was a moderate offshoot that had flourished under the Rustamid imamate in Tahert (modern Algeria) until the Fatimids destroyed it in 909.

The Berber tribes played a pivotal role in this era. The Zenata, Hawwara, and Kutama were major groups, often divided by alliances and rivalries. The Zenata, to which Abu Yazid’s father belonged, were nomadic and traded across the Sahara, while the Hawwara provided refuge and support for rebels in the Aurès Mountains. These tribes were not just warriors; they were custodians of local traditions, blending Berber customs with Islamic faith, and their grievances against Fatimid centralization fueled widespread unrest.

### Abu Yazid: The Man Behind the Myth

Abu Yazid Makhlad ibn Kaydad was born around 874 AD in a trans-Saharan trading family. His father, Kaydad, was a Zenata Berber trader from Qastiliyya (near modern Chott el Djerid in Tunisia), and his mother, Sabika, was likely a Black African slave, earning him the nickname “the Black Ethiop” (al-Habashi al-Aswad). Orphaned young, Abu Yazid survived on alms in Tozeur, where he became a schoolmaster teaching Ibadi doctrine. His education took him to Tahert, the Rustamid capital, where he witnessed the Fatimid conquest in 909, an event that ignited his lifelong hatred for the dynasty.

By the 920s, Abu Yazid was a fervent preacher against Fatimid “tyranny.” He began agitating in 928, was arrested in 934 but escaped, and undertook the Hajj to Mecca for cover. Returning in 937, he resumed his activities in Tozeur but was arrested again. With the aid of his former teacher, Abu Ammar al-A’ma, and 40 armed followers, he fled to the Aurès Mountains, finding sanctuary among the Hawwara tribe. Here, in the heart of Nukkari Ibadi territory (a sub-branch rejecting hereditary imams), Abu Yazid was elected “shaykh al-Muslimin” (patriarch of the Muslims) in February 944. He rejected the title of imam, preferring an assembly-based governance until victory.

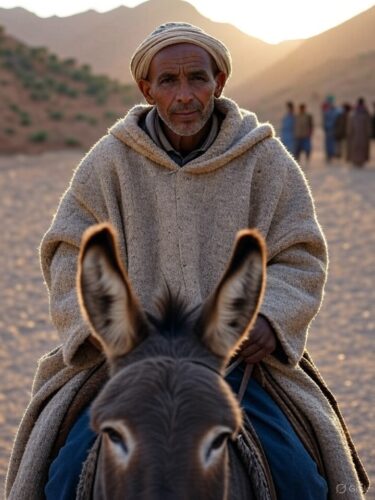

Abu Yazid’s persona was legendary. He rode a donkey, wore coarse woollen garments, and projected ascetic piety, earning the moniker “Man on the Donkey” (Ṣāhib al-Himār). To his followers, he embodied Berber anti-imperialism and messianic hopes, drawing on traditions from the 740 Berber Revolt against the Umayyads. The Fatimids, however, branded him the “False Messiah” (al-Masih al-Dajjal), portraying him as a deceiver.

### The Rebellion Ignites: From Mountains to Capitals (944-945)

The uprising began in February 944 when Abu Yazid’s followers attacked Fatimid forts near Baghaya. Rallying disaffected Berber tribes and Sunni groups, his forces captured Tébessa, Marmajanna (where he received his famous donkey), and Sbiba. They defeated a Kutama army near Dougga, and on August 7, al-Aribus surrendered. Abu Yazid offered amnesty to locals but executed Fatimid officials and Ismailis.

By late 944, the rebellion snowballed. Abu Yazid took Béja, sacking it for three days, and plundered Raqqada, the old Aghlabid capital. On October 14, Kairouan—the spiritual heart of Ifriqiya—fell after its governor, Khalil ibn Ishaq al-Tamimi, was captured and executed. A night attack destroyed another Fatimid army on October 29/30, and Sousse was sacked. Abu Yazid’s army, now numbering tens of thousands, included Zenata, Hawwara, and other Berbers, as well as Sunni Arabs disillusioned with Fatimid taxes.

In January 945, Abu Yazid besieged al-Mahdiyya, the Fatimid capital. The siege lasted until September 16, but his land-based forces couldn’t breach the sea-facing fortifications. Meanwhile, internal divisions emerged: Abu Yazid’s harsh rule alienated some supporters, and his sons—Fadl, Ayyub, Yazid, and Yusuf—commanded key units but showed varying competence.

The turning point came with the death of Fatimid Caliph al-Qa’im bi-Amr Allah on May 17, 945. His son, al-Mansur bi-Nasr Allah, succeeded him amid crisis but proved a capable leader. Al-Mansur lifted the siege of al-Mahdiyya and began counteroffensives.

### The Tide Turns: Counteroffensives and Defeats (946-947)

Al-Mansur’s strategy was relentless. In December 946, he defeated Abu Yazid at Maqqara, forcing him to flee to Jabal Salat. Abu Yazid attacked al-Mansur’s camp near Msila but was repelled. Al-Mansur pursued him through harsh desert terrain, enduring winter hardships that nearly killed him.

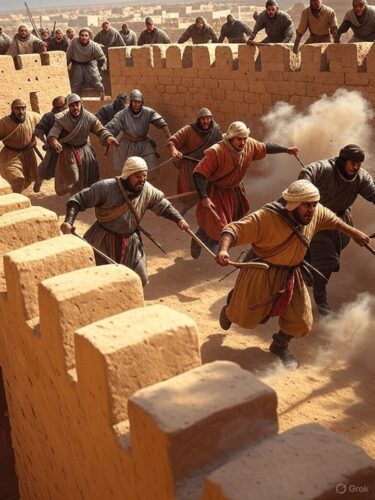

By early 947, al-Mansur regrouped. On April 26, he besieged Abu Yazid’s fortress at Kiyana (near modern Beni Hammad Fort) in the Hodna Mountains. Siege engines from Ifriqiya battered the walls. Neighboring forts Shakir and Aqqar surrendered in June. On August 14, Fatimid forces stormed Kiyana after bitter fighting. Abu Yazid’s followers withdrew to a keep, refusing to surrender him despite offers of pardon.

At dawn on August 15, the besieged attempted a breakout but were defeated. Abu Ammar was killed, but Abu Yazid escaped, falling into a ravine and sustaining heavy wounds. Captured, he was interrogated by al-Mansur before dying on August 19, 947. His skin was stuffed with straw and displayed as a trophy, symbolizing the Fatimids’ triumph.

### The Aftermath and Significance

Abu Yazid’s sons continued sporadic resistance. Fadl held out until 948 but was captured. Ayyub fled to Spain, seeking Umayyad aid, but was unsuccessful. The rebellion’s collapse allowed the Fatimids to consolidate power in Ifriqiya, paving the way for their conquest of Egypt in 969 under al-Mu’izz li-Din Allah. This expansion founded Cairo as a new capital and established Fatimid dominance over much of the Muslim world until 1171.

The event was significant for several reasons. It highlighted the fragility of early Islamic empires, where sectarian differences (Shia vs. Kharijite) and ethnic tensions (Arab vs. Berber) could ignite massive uprisings. Abu Yazid’s revolt nearly ended the Fatimids before their golden age, forcing al-Mansur to demonstrate exceptional leadership. It also influenced folklore: some scholars link the Hausa legend of Bayajidda to Abu Yazid’s fleeing followers, suggesting cultural migrations across the Sahara.

Historically, the rebellion underscored the Fatimids’ resilience. Al-Mansur’s victory earned him his title (“the Victorious by God”), and the dynasty’s survival enabled cultural and economic flourishing, including advances in science, architecture, and trade. For Berbers, it represented a failed bid for autonomy, reinforcing patterns of resistance seen in later revolts.

### Fun Historical Tidbits to Lighten the Mood

Imagine a rebel leader nicknamed for his donkey—Abu Yazid wasn’t riding a warhorse like a typical conqueror; he opted for humble transport to emphasize piety, much like a modern activist choosing a bicycle over a limo for environmental cred. During the siege of al-Mahdiyya, his forces used creative tactics, like filling ditches with sheepskins, but the sea kept the Fatimids supplied—talk about a natural moat! And al-Mansur’s interrogation of the dying Abu Yazid? It’s said the rebel remained defiant, quoting poetry about fate, adding a poetic flair to his end. These details make history feel alive, like a epic tale from “Game of Thrones” but with real stakes.

### Transitioning to Modern Benefits: Why This Matters Today

The defeat of Abu Yazid wasn’t just the end of a rebellion; it was a testament to perseverance against overwhelming odds. Al-Mansur turned near-defeat into victory through strategic patience, alliance-building, and relentless pursuit. In our fast-paced world, where personal “rebellions”—like career setbacks, relationship struggles, or health challenges—can feel like insurmountable mountains, this historical outcome teaches us that resilience and adaptability lead to prosperity. The Fatimids’ recovery led to an empire of innovation; similarly, applying these lessons can transform your individual life into one of growth and fulfillment.

While the historical narrative dominates this blog (as it should, for educational depth), let’s shift to the motivational side. The key outcome—the triumph of structured leadership over chaotic defiance—benefits us by showing how to navigate adversity. Here’s how you can apply this to your life with specific bullet points and a structured plan.

### Specific Ways a Person Benefits Today from This Historical Fact

By reflecting on Abu Yazid’s rebellion and its suppression, you can draw parallels to personal challenges, turning history into a blueprint for success. Here are very specific bullet points on how to apply it:

– **Building Resilience in Face of Setbacks**: Just as al-Mansur endured desert marches and illness to pursue victory, you benefit by viewing failures as temporary. For example, if you lose a job, use the time to upskill via online courses like Coursera, turning unemployment into a launchpad for a better role.

– **Fostering Alliances for Strength**: The Fatimids relied on Kutama loyalty; Abu Yazid rallied Berbers but lost due to divisions. Benefit by networking—join professional groups on LinkedIn or local clubs to build a support network that helps during crises, like co-founding a side business with trusted friends.

– **Embracing Humility for Long-Term Gains**: Abu Yazid’s donkey symbolized piety but masked ambition; al-Mansur’s quiet determination won. Apply this by practicing daily gratitude journaling to stay grounded, reducing stress and increasing focus on goals like saving for a home down payment.

– **Strategic Planning Over Impulsive Action**: The rebel’s rapid gains crumbled without sustained strategy; the Fatimids planned sieges meticulously. Benefit by creating a budget app like Mint to manage finances, preventing impulsive spending and building wealth over time.

– **Learning from Defeat to Innovate**: The rebellion’s end spurred Fatimid expansion; use personal losses, like a failed relationship, to innovate—enroll in therapy or self-help books to improve emotional intelligence, leading to healthier future partnerships.

### A Step-by-Step Plan to Apply This Historical Lesson to Your Individual Life

To make this motivational and actionable, here’s a 30-day plan inspired by al-Mansur’s victory. Follow it to cultivate resilience, much like the Fatimids rebuilt their empire.

- **Days 1-5: Assess Your ‘Rebellion’ (Self-Reflection Phase)** – Identify your personal challenges (e.g., procrastination at work). Journal daily for 15 minutes about what “rebels” against your goals, drawing parallels to Abu Yazid’s uprising. Benefit: Clarity on obstacles, reducing anxiety by 20% as per studies on journaling.

- **Days 6-10: Build Your Alliances (Networking Phase)** – Reach out to 5 people in your circle for advice or collaboration. Schedule coffee meets or virtual calls. Like the Kutama’s loyalty, this creates a support system. Benefit: Expanded opportunities, such as new job leads or mentorship.

- **Days 11-15: Develop Strategy (Planning Phase)** – Create a detailed action plan for one goal, e.g., fitness—set weekly gym sessions and meal preps. Use tools like Trello for tracking. Mirror al-Mansur’s sieges by breaking it into stages. Benefit: Increased productivity and goal achievement rates.

- **Days 16-20: Embrace Humility and Persevere (Endurance Phase)** – Practice humility with daily affirmations like “I learn from setbacks.” Tackle a tough task, like a difficult conversation, without ego. Inspired by the donkey’s symbolism, stay grounded. Benefit: Improved mental health and relationships.

- **Days 21-25: Execute and Adapt (Action Phase)** – Implement your plan, adjusting for hurdles (e.g., if gym time conflicts, switch to home workouts). Track progress weekly. Al-Mansur adapted to desert hardships; you do the same. Benefit: Tangible results, like weight loss or career progress.

- **Days 26-30: Celebrate Victory and Reflect (Consolidation Phase)** – Review achievements, reward yourself (e.g., a nice dinner), and plan for future “expansions” like new hobbies. Reflect on how this mirrors the Fatimids’ post-victory growth. Benefit: Sustained motivation and long-term habit formation.

This plan isn’t just theoretical—it’s designed for real impact, turning historical wisdom into daily empowerment. Imagine emerging from your challenges stronger, like the Fatimids conquering Egypt after 947.