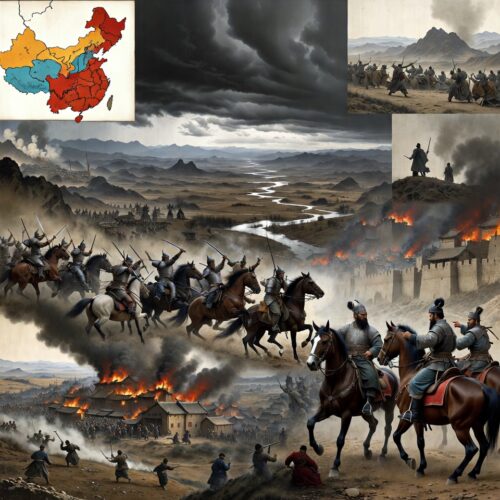

Imagine this: It's a chilly February morning in 960 AD, and a battle-hardened general named Zhao Kuangyin is nursing what must have been the mother of all hangovers. His troops, supposedly marching off to fend off invaders from the north, decide instead to throw him the ultimate surprise – draping him in a bright yellow imperial robe and yelling, "You're the emperor now!" Sounds like a scene from a bad comedy sketch, right? But this wasn't just barracks banter gone wild; it was the spark that ignited the Song Dynasty, one of China's most innovative and prosperous eras. On February 4, 960, Zhao Kuangyin officially ascended as Emperor Taizu, ending a chaotic century of warlords and kickstarting three centuries of cultural brilliance, economic boom, and inventions that still echo today. Buckle up for a deep dive into this pivotal moment – mostly history with a dash of hilarity – and stick around for how this ancient power grab can supercharge your modern life. To set the stage, we have to rewind to the messy aftermath of the Tang Dynasty's collapse in 907 AD. China, once a unified powerhouse under the Tang (618–907), had splintered into a patchwork of squabbling kingdoms. Historians call this the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960), but it might as well have been dubbed "The Era of Endless Coups and Bad Haircuts." In the north, five short-lived dynasties – Later Liang, Later Tang, Later Jin, Later Han, and Later Zhou – rose and fell like poorly stacked dominoes, each lasting about as long as a modern celebrity marriage. Down south, ten independent kingdoms popped up, from the rice paddies of the Yangtze to the mountains of Sichuan, each ruled by self-proclaimed kings who spent more time plotting against neighbors than governing.

This fragmentation wasn't just political; it was a full-blown societal meltdown. Armies roamed like rogue gangs, pillaging villages and extorting taxes. Famine stalked the land as irrigation systems crumbled from neglect. Trade routes, once buzzing with silk and spices, turned into bandit highways. And let's not forget the constant invasions from nomadic groups like the Khitans (who founded the Liao Dynasty in the northeast) and the Tanguts (who'd later form the Western Xia). It was a time when loyalty was as reliable as a chocolate teapot – generals overthrew emperors faster than you could say "dynastic cycle."

To set the stage, we have to rewind to the messy aftermath of the Tang Dynasty's collapse in 907 AD. China, once a unified powerhouse under the Tang (618–907), had splintered into a patchwork of squabbling kingdoms. Historians call this the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960), but it might as well have been dubbed "The Era of Endless Coups and Bad Haircuts." In the north, five short-lived dynasties – Later Liang, Later Tang, Later Jin, Later Han, and Later Zhou – rose and fell like poorly stacked dominoes, each lasting about as long as a modern celebrity marriage. Down south, ten independent kingdoms popped up, from the rice paddies of the Yangtze to the mountains of Sichuan, each ruled by self-proclaimed kings who spent more time plotting against neighbors than governing.

This fragmentation wasn't just political; it was a full-blown societal meltdown. Armies roamed like rogue gangs, pillaging villages and extorting taxes. Famine stalked the land as irrigation systems crumbled from neglect. Trade routes, once buzzing with silk and spices, turned into bandit highways. And let's not forget the constant invasions from nomadic groups like the Khitans (who founded the Liao Dynasty in the northeast) and the Tanguts (who'd later form the Western Xia). It was a time when loyalty was as reliable as a chocolate teapot – generals overthrew emperors faster than you could say "dynastic cycle." Enter Zhao Kuangyin, our reluctant hero. Born on March 21, 927, in Luoyang (then a faded glory of the Tang era), Zhao came from a modest military family. His father, Zhao Hongyin, was a cavalry officer, and young Zhao grew up swinging swords instead of studying classics – though he'd later prove he could handle both. By his teens, China was already in the Five Dynasties blender, and Zhao joined the fray as a soldier under the Later Tang. He was no pretty-boy scholar; descriptions paint him as tall, broad-shouldered, with a fierce gaze and a beard that could intimidate a bear. But he had brains to match the brawn: a master tactician who rose through ranks by winning battles and earning troops' respect.

Zhao's big break came during the Later Zhou Dynasty (951–960), the last of the northern five. Founded by Guo Wei, a no-nonsense eunuch-turned-emperor, the Zhou aimed to stabilize the north. Guo's successor, Chai Rong (Emperor Shizong), was a reformer who expanded territory and built a professional army. Zhao Kuangyin caught Shizong's eye, becoming a top commander of the palace guards. He led daring campaigns, like the 959 assault on the Southern Tang, where his forces captured key cities along the Huai River. Shizong trusted him implicitly, even adopting him into the imperial fold in a symbolic gesture.

But fate – or ambition – intervened. In 959, Shizong died suddenly, leaving his seven-year-old son, Guo Zongxun (Emperor Gong), on the throne. The court was a viper's nest: regents bickered, and border threats loomed. The Northern Han, allied with the Khitan Liao, smelled weakness and invaded. In early 960, the Zhou court dispatched Zhao Kuangyin with an army to repel them. He marched north from Kaifeng, the capital, with his brother Zhao Kuangyi (later Emperor Taizong) and key generals like Shi Shouxin and Wang Shenqi at his side.

Here's where it gets comically dramatic. On February 3, 960, the army camped at Chenqiao Station, about 20 miles northeast of Kaifeng. Official histories claim Zhao was blitzed drunk that night, passed out in his tent after a boozy send-off. But come dawn, his soldiers "mutinied." They burst in, waving a yellow robe – the color reserved for emperors – and forced it over his head, proclaiming him the Son of Heaven. Zhao, feigning shock (historians debate if he was really surprised), protested: "The emperor is but a child; how can I usurp?" The troops insisted, citing omens like a solar eclipse (which didn't actually happen) and a mysterious wooden tablet from Shizong's era prophesying a Zhao takeover.

Enter Zhao Kuangyin, our reluctant hero. Born on March 21, 927, in Luoyang (then a faded glory of the Tang era), Zhao came from a modest military family. His father, Zhao Hongyin, was a cavalry officer, and young Zhao grew up swinging swords instead of studying classics – though he'd later prove he could handle both. By his teens, China was already in the Five Dynasties blender, and Zhao joined the fray as a soldier under the Later Tang. He was no pretty-boy scholar; descriptions paint him as tall, broad-shouldered, with a fierce gaze and a beard that could intimidate a bear. But he had brains to match the brawn: a master tactician who rose through ranks by winning battles and earning troops' respect.

Zhao's big break came during the Later Zhou Dynasty (951–960), the last of the northern five. Founded by Guo Wei, a no-nonsense eunuch-turned-emperor, the Zhou aimed to stabilize the north. Guo's successor, Chai Rong (Emperor Shizong), was a reformer who expanded territory and built a professional army. Zhao Kuangyin caught Shizong's eye, becoming a top commander of the palace guards. He led daring campaigns, like the 959 assault on the Southern Tang, where his forces captured key cities along the Huai River. Shizong trusted him implicitly, even adopting him into the imperial fold in a symbolic gesture.

But fate – or ambition – intervened. In 959, Shizong died suddenly, leaving his seven-year-old son, Guo Zongxun (Emperor Gong), on the throne. The court was a viper's nest: regents bickered, and border threats loomed. The Northern Han, allied with the Khitan Liao, smelled weakness and invaded. In early 960, the Zhou court dispatched Zhao Kuangyin with an army to repel them. He marched north from Kaifeng, the capital, with his brother Zhao Kuangyi (later Emperor Taizong) and key generals like Shi Shouxin and Wang Shenqi at his side.

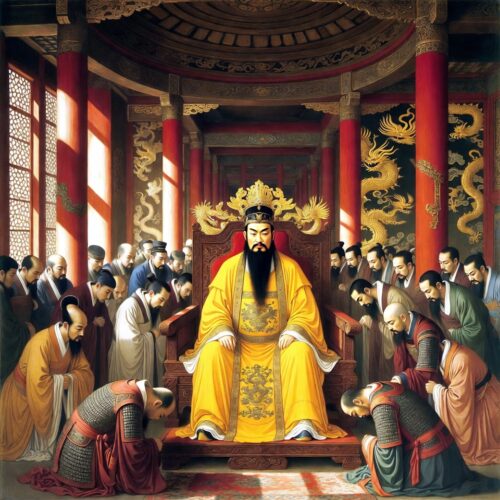

Here's where it gets comically dramatic. On February 3, 960, the army camped at Chenqiao Station, about 20 miles northeast of Kaifeng. Official histories claim Zhao was blitzed drunk that night, passed out in his tent after a boozy send-off. But come dawn, his soldiers "mutinied." They burst in, waving a yellow robe – the color reserved for emperors – and forced it over his head, proclaiming him the Son of Heaven. Zhao, feigning shock (historians debate if he was really surprised), protested: "The emperor is but a child; how can I usurp?" The troops insisted, citing omens like a solar eclipse (which didn't actually happen) and a mysterious wooden tablet from Shizong's era prophesying a Zhao takeover. Modern scholars aren't buying the "reluctant emperor" act. Evidence suggests Zhao orchestrated the whole thing. His inner circle included plotters like Zhao Pu, a cunning advisor who'd later become chancellor. The mutiny was bloodless – no massacres, no looting – unlike previous coups. It was a masterclass in PR: Zhao ordered his men to protect civilians and the young emperor, framing the takeover as a necessary stabilization. By February 4, they marched back to Kaifeng unopposed. The palace guards, commanded by Zhao's allies, opened the gates. Little Emperor Gong abdicated peacefully, and Zhao Kuangyin was coronated as Emperor Taizu, founding the Song Dynasty. He chose "Song" after his old fief in Songzhou, symbolizing a fresh start.

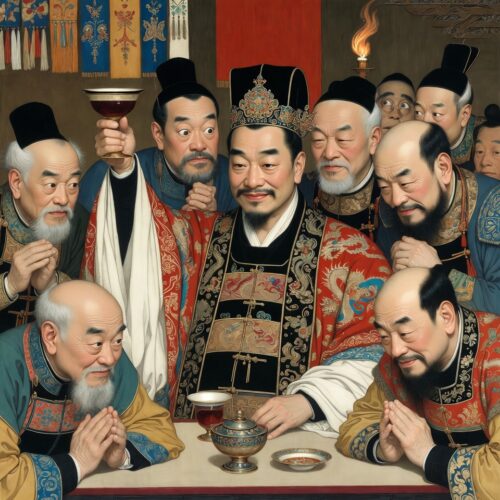

Taizu's reign (960–976) was a whirlwind of reforms that turned chaos into China's Renaissance. First, he consolidated power with style – no purges, just clever maneuvers. In a famous 961 incident called "Releasing Military Power Over a Cup of Wine," Taizu invited his top generals to a banquet. After a few rounds, he lamented how emperors feared ambitious commanders (hint, hint). The generals, sensing the vibe, resigned their posts the next day for cushy titles and pensions. Taizu replaced them with civil bureaucrats, centralizing command and ending the jiedushi (military governor) system that had fueled the Five Dynasties' instability.

Militarily, Taizu was relentless. His "southern first" strategy prioritized conquering the weaker southern kingdoms before tackling northern nomads. By 963, he'd absorbed Jingnan and Hunan. In 965, he crushed the Shu in Sichuan, capturing 30,000 troops without a fight by outflanking them. The Southern Han fell in 971 after a naval siege on Guangzhou, yielding elephant troops and exotic treasures. Wuyue surrendered peacefully in 978 (after Taizu's death, but under his plans). By then, the Song controlled most of southern China, reuniting lands fractured since the Tang.

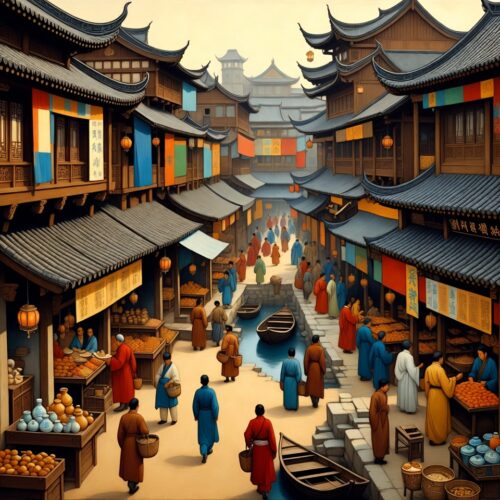

Economically, Taizu was a visionary. He promoted agriculture by distributing seeds, repairing dikes, and encouraging migration to underfarmed areas. Iron production soared – Song China produced more iron than 18th-century Europe. He standardized currency, minting bronze coins that stabilized trade. Kaifeng boomed as the capital: a metropolis of over a million, with canals linking it to the Yangtze, bustling markets, and innovations like restaurants (yes, the Song invented dining out). Taizu also fostered culture: he expanded the imperial exams, making meritocracy the path to power. Scholars flocked to court, laying groundwork for Neo-Confucianism.

Modern scholars aren't buying the "reluctant emperor" act. Evidence suggests Zhao orchestrated the whole thing. His inner circle included plotters like Zhao Pu, a cunning advisor who'd later become chancellor. The mutiny was bloodless – no massacres, no looting – unlike previous coups. It was a masterclass in PR: Zhao ordered his men to protect civilians and the young emperor, framing the takeover as a necessary stabilization. By February 4, they marched back to Kaifeng unopposed. The palace guards, commanded by Zhao's allies, opened the gates. Little Emperor Gong abdicated peacefully, and Zhao Kuangyin was coronated as Emperor Taizu, founding the Song Dynasty. He chose "Song" after his old fief in Songzhou, symbolizing a fresh start.

Taizu's reign (960–976) was a whirlwind of reforms that turned chaos into China's Renaissance. First, he consolidated power with style – no purges, just clever maneuvers. In a famous 961 incident called "Releasing Military Power Over a Cup of Wine," Taizu invited his top generals to a banquet. After a few rounds, he lamented how emperors feared ambitious commanders (hint, hint). The generals, sensing the vibe, resigned their posts the next day for cushy titles and pensions. Taizu replaced them with civil bureaucrats, centralizing command and ending the jiedushi (military governor) system that had fueled the Five Dynasties' instability.

Militarily, Taizu was relentless. His "southern first" strategy prioritized conquering the weaker southern kingdoms before tackling northern nomads. By 963, he'd absorbed Jingnan and Hunan. In 965, he crushed the Shu in Sichuan, capturing 30,000 troops without a fight by outflanking them. The Southern Han fell in 971 after a naval siege on Guangzhou, yielding elephant troops and exotic treasures. Wuyue surrendered peacefully in 978 (after Taizu's death, but under his plans). By then, the Song controlled most of southern China, reuniting lands fractured since the Tang.

Economically, Taizu was a visionary. He promoted agriculture by distributing seeds, repairing dikes, and encouraging migration to underfarmed areas. Iron production soared – Song China produced more iron than 18th-century Europe. He standardized currency, minting bronze coins that stabilized trade. Kaifeng boomed as the capital: a metropolis of over a million, with canals linking it to the Yangtze, bustling markets, and innovations like restaurants (yes, the Song invented dining out). Taizu also fostered culture: he expanded the imperial exams, making meritocracy the path to power. Scholars flocked to court, laying groundwork for Neo-Confucianism. But Taizu wasn't flawless. He obsessed over loyalty, rotating officials frequently to prevent cliques – a policy that bred bureaucracy. Northern borders remained vulnerable: in 979 (post-Taizu), the Song failed to conquer the Liao, leading to the 1005 Chanyuan Treaty, where Song paid "gifts" for peace. Still, Taizu's foundations endured.

His death on November 14, 976, is shrouded in mystery – the "axe and candle shadows" legend. Official records say natural causes at 49, but folklore claims his brother Kuangyi (Taizong) murdered him, inspired by a shadowy axe sound during a stormy night chat. Taizong succeeded, but suspicions lingered, fueling Song literature.

Under Taizong (976–997) and successors, the Song peaked. Inventions exploded: gunpowder weapons (fire lances in 969), movable-type printing (Bisheng in 1040s), the magnetic compass for navigation. Art flourished – landscape paintings by Fan Kuan captured misty mountains; poetry by Su Shi blended wit and wisdom. Economy-wise, rice yields doubled with Champa strains; paper money emerged in 1023. Population hit 100 million by 1100. But military weakness bit: the Jurchen Jin overran the north in 1127, forcing the Southern Song (1127–1279) retreat to Hangzhou. Yet even then, culture thrived until Mongol conquest in 1279.

The Song's legacy? It was China's "modern" age: urban, commercial, innovative. Without Taizu's mutiny, no porcelain explosion (exported to Europe), no Shen Kuo's scientific encyclopedia (dreaming of gears and magnets), no economic miracle that made Song GDP a quarter of the world's.

Now, for the 10% motivation: How does a 10th-century coup apply to your life? Taizu didn't just seize a throne; he pivoted from chaos to creation, turning a "mutiny" into mastery. Benefit today by channeling his strategic smarts – plan your "power grabs" (career moves, habit changes) with precision, not force. Here's a specific plan:

- **Assess Your Battlefield:** Like Taizu scanning the Five Dynasties mess, map your current chaos. Bullet points: List three "kingdoms" draining you (e.g., toxic job, cluttered home, neglected health). For each, note threats (stress, disorganization) and opportunities (new skills, decluttering apps).

But Taizu wasn't flawless. He obsessed over loyalty, rotating officials frequently to prevent cliques – a policy that bred bureaucracy. Northern borders remained vulnerable: in 979 (post-Taizu), the Song failed to conquer the Liao, leading to the 1005 Chanyuan Treaty, where Song paid "gifts" for peace. Still, Taizu's foundations endured.

His death on November 14, 976, is shrouded in mystery – the "axe and candle shadows" legend. Official records say natural causes at 49, but folklore claims his brother Kuangyi (Taizong) murdered him, inspired by a shadowy axe sound during a stormy night chat. Taizong succeeded, but suspicions lingered, fueling Song literature.

Under Taizong (976–997) and successors, the Song peaked. Inventions exploded: gunpowder weapons (fire lances in 969), movable-type printing (Bisheng in 1040s), the magnetic compass for navigation. Art flourished – landscape paintings by Fan Kuan captured misty mountains; poetry by Su Shi blended wit and wisdom. Economy-wise, rice yields doubled with Champa strains; paper money emerged in 1023. Population hit 100 million by 1100. But military weakness bit: the Jurchen Jin overran the north in 1127, forcing the Southern Song (1127–1279) retreat to Hangzhou. Yet even then, culture thrived until Mongol conquest in 1279.

The Song's legacy? It was China's "modern" age: urban, commercial, innovative. Without Taizu's mutiny, no porcelain explosion (exported to Europe), no Shen Kuo's scientific encyclopedia (dreaming of gears and magnets), no economic miracle that made Song GDP a quarter of the world's.

Now, for the 10% motivation: How does a 10th-century coup apply to your life? Taizu didn't just seize a throne; he pivoted from chaos to creation, turning a "mutiny" into mastery. Benefit today by channeling his strategic smarts – plan your "power grabs" (career moves, habit changes) with precision, not force. Here's a specific plan:

- **Assess Your Battlefield:** Like Taizu scanning the Five Dynasties mess, map your current chaos. Bullet points: List three "kingdoms" draining you (e.g., toxic job, cluttered home, neglected health). For each, note threats (stress, disorganization) and opportunities (new skills, decluttering apps). - **Orchestrate Your Mutiny:** Don't wait for a hangover surprise; stage a calculated shift. Bullet points: Choose one area; gather "allies" (friends, apps, books). Set a "Chenqiao moment" – a deadline (e.g., apply for that promotion by week's end). Feign reluctance if needed – tell yourself "I'm not ready," then do it anyway for that dramatic flair.

- **Consolidate with Wine (or Wisdom):** Post-"coup," secure gains like Taizu's banquet. Bullet points: Reward supporters (thank mentors); demote "generals" (bad habits) gently – swap scrolling for reading. Centralize control: Daily rituals (morning journal) to prevent backsliding.

- **Expand and Innovate:** Taizu unified south first; grow your empire incrementally. Bullet points: Tackle small wins (cook healthy meals thrice weekly); innovate (try a new hobby like Song inventors). Track progress in a "dynasty diary" – note inventions (personal hacks) and alliances.

Follow this four-step plan weekly: Assess Sunday, mutiny Monday-Wednesday, consolidate Thursday-Friday, expand Saturday. In months, you'll build your "Song era" – prosperous, innovative, and hilariously unstoppable. Who knew ancient history could be your life coach?

- **Orchestrate Your Mutiny:** Don't wait for a hangover surprise; stage a calculated shift. Bullet points: Choose one area; gather "allies" (friends, apps, books). Set a "Chenqiao moment" – a deadline (e.g., apply for that promotion by week's end). Feign reluctance if needed – tell yourself "I'm not ready," then do it anyway for that dramatic flair.

- **Consolidate with Wine (or Wisdom):** Post-"coup," secure gains like Taizu's banquet. Bullet points: Reward supporters (thank mentors); demote "generals" (bad habits) gently – swap scrolling for reading. Centralize control: Daily rituals (morning journal) to prevent backsliding.

- **Expand and Innovate:** Taizu unified south first; grow your empire incrementally. Bullet points: Tackle small wins (cook healthy meals thrice weekly); innovate (try a new hobby like Song inventors). Track progress in a "dynasty diary" – note inventions (personal hacks) and alliances.

Follow this four-step plan weekly: Assess Sunday, mutiny Monday-Wednesday, consolidate Thursday-Friday, expand Saturday. In months, you'll build your "Song era" – prosperous, innovative, and hilariously unstoppable. Who knew ancient history could be your life coach?

To set the stage, we have to rewind to the messy aftermath of the Tang Dynasty's collapse in 907 AD. China, once a unified powerhouse under the Tang (618–907), had splintered into a patchwork of squabbling kingdoms. Historians call this the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960), but it might as well have been dubbed "The Era of Endless Coups and Bad Haircuts." In the north, five short-lived dynasties – Later Liang, Later Tang, Later Jin, Later Han, and Later Zhou – rose and fell like poorly stacked dominoes, each lasting about as long as a modern celebrity marriage. Down south, ten independent kingdoms popped up, from the rice paddies of the Yangtze to the mountains of Sichuan, each ruled by self-proclaimed kings who spent more time plotting against neighbors than governing. This fragmentation wasn't just political; it was a full-blown societal meltdown. Armies roamed like rogue gangs, pillaging villages and extorting taxes. Famine stalked the land as irrigation systems crumbled from neglect. Trade routes, once buzzing with silk and spices, turned into bandit highways. And let's not forget the constant invasions from nomadic groups like the Khitans (who founded the Liao Dynasty in the northeast) and the Tanguts (who'd later form the Western Xia). It was a time when loyalty was as reliable as a chocolate teapot – generals overthrew emperors faster than you could say "dynastic cycle."

Enter Zhao Kuangyin, our reluctant hero. Born on March 21, 927, in Luoyang (then a faded glory of the Tang era), Zhao came from a modest military family. His father, Zhao Hongyin, was a cavalry officer, and young Zhao grew up swinging swords instead of studying classics – though he'd later prove he could handle both. By his teens, China was already in the Five Dynasties blender, and Zhao joined the fray as a soldier under the Later Tang. He was no pretty-boy scholar; descriptions paint him as tall, broad-shouldered, with a fierce gaze and a beard that could intimidate a bear. But he had brains to match the brawn: a master tactician who rose through ranks by winning battles and earning troops' respect. Zhao's big break came during the Later Zhou Dynasty (951–960), the last of the northern five. Founded by Guo Wei, a no-nonsense eunuch-turned-emperor, the Zhou aimed to stabilize the north. Guo's successor, Chai Rong (Emperor Shizong), was a reformer who expanded territory and built a professional army. Zhao Kuangyin caught Shizong's eye, becoming a top commander of the palace guards. He led daring campaigns, like the 959 assault on the Southern Tang, where his forces captured key cities along the Huai River. Shizong trusted him implicitly, even adopting him into the imperial fold in a symbolic gesture. But fate – or ambition – intervened. In 959, Shizong died suddenly, leaving his seven-year-old son, Guo Zongxun (Emperor Gong), on the throne. The court was a viper's nest: regents bickered, and border threats loomed. The Northern Han, allied with the Khitan Liao, smelled weakness and invaded. In early 960, the Zhou court dispatched Zhao Kuangyin with an army to repel them. He marched north from Kaifeng, the capital, with his brother Zhao Kuangyi (later Emperor Taizong) and key generals like Shi Shouxin and Wang Shenqi at his side. Here's where it gets comically dramatic. On February 3, 960, the army camped at Chenqiao Station, about 20 miles northeast of Kaifeng. Official histories claim Zhao was blitzed drunk that night, passed out in his tent after a boozy send-off. But come dawn, his soldiers "mutinied." They burst in, waving a yellow robe – the color reserved for emperors – and forced it over his head, proclaiming him the Son of Heaven. Zhao, feigning shock (historians debate if he was really surprised), protested: "The emperor is but a child; how can I usurp?" The troops insisted, citing omens like a solar eclipse (which didn't actually happen) and a mysterious wooden tablet from Shizong's era prophesying a Zhao takeover.

Modern scholars aren't buying the "reluctant emperor" act. Evidence suggests Zhao orchestrated the whole thing. His inner circle included plotters like Zhao Pu, a cunning advisor who'd later become chancellor. The mutiny was bloodless – no massacres, no looting – unlike previous coups. It was a masterclass in PR: Zhao ordered his men to protect civilians and the young emperor, framing the takeover as a necessary stabilization. By February 4, they marched back to Kaifeng unopposed. The palace guards, commanded by Zhao's allies, opened the gates. Little Emperor Gong abdicated peacefully, and Zhao Kuangyin was coronated as Emperor Taizu, founding the Song Dynasty. He chose "Song" after his old fief in Songzhou, symbolizing a fresh start. Taizu's reign (960–976) was a whirlwind of reforms that turned chaos into China's Renaissance. First, he consolidated power with style – no purges, just clever maneuvers. In a famous 961 incident called "Releasing Military Power Over a Cup of Wine," Taizu invited his top generals to a banquet. After a few rounds, he lamented how emperors feared ambitious commanders (hint, hint). The generals, sensing the vibe, resigned their posts the next day for cushy titles and pensions. Taizu replaced them with civil bureaucrats, centralizing command and ending the jiedushi (military governor) system that had fueled the Five Dynasties' instability. Militarily, Taizu was relentless. His "southern first" strategy prioritized conquering the weaker southern kingdoms before tackling northern nomads. By 963, he'd absorbed Jingnan and Hunan. In 965, he crushed the Shu in Sichuan, capturing 30,000 troops without a fight by outflanking them. The Southern Han fell in 971 after a naval siege on Guangzhou, yielding elephant troops and exotic treasures. Wuyue surrendered peacefully in 978 (after Taizu's death, but under his plans). By then, the Song controlled most of southern China, reuniting lands fractured since the Tang. Economically, Taizu was a visionary. He promoted agriculture by distributing seeds, repairing dikes, and encouraging migration to underfarmed areas. Iron production soared – Song China produced more iron than 18th-century Europe. He standardized currency, minting bronze coins that stabilized trade. Kaifeng boomed as the capital: a metropolis of over a million, with canals linking it to the Yangtze, bustling markets, and innovations like restaurants (yes, the Song invented dining out). Taizu also fostered culture: he expanded the imperial exams, making meritocracy the path to power. Scholars flocked to court, laying groundwork for Neo-Confucianism.

But Taizu wasn't flawless. He obsessed over loyalty, rotating officials frequently to prevent cliques – a policy that bred bureaucracy. Northern borders remained vulnerable: in 979 (post-Taizu), the Song failed to conquer the Liao, leading to the 1005 Chanyuan Treaty, where Song paid "gifts" for peace. Still, Taizu's foundations endured. His death on November 14, 976, is shrouded in mystery – the "axe and candle shadows" legend. Official records say natural causes at 49, but folklore claims his brother Kuangyi (Taizong) murdered him, inspired by a shadowy axe sound during a stormy night chat. Taizong succeeded, but suspicions lingered, fueling Song literature. Under Taizong (976–997) and successors, the Song peaked. Inventions exploded: gunpowder weapons (fire lances in 969), movable-type printing (Bisheng in 1040s), the magnetic compass for navigation. Art flourished – landscape paintings by Fan Kuan captured misty mountains; poetry by Su Shi blended wit and wisdom. Economy-wise, rice yields doubled with Champa strains; paper money emerged in 1023. Population hit 100 million by 1100. But military weakness bit: the Jurchen Jin overran the north in 1127, forcing the Southern Song (1127–1279) retreat to Hangzhou. Yet even then, culture thrived until Mongol conquest in 1279. The Song's legacy? It was China's "modern" age: urban, commercial, innovative. Without Taizu's mutiny, no porcelain explosion (exported to Europe), no Shen Kuo's scientific encyclopedia (dreaming of gears and magnets), no economic miracle that made Song GDP a quarter of the world's. Now, for the 10% motivation: How does a 10th-century coup apply to your life? Taizu didn't just seize a throne; he pivoted from chaos to creation, turning a "mutiny" into mastery. Benefit today by channeling his strategic smarts – plan your "power grabs" (career moves, habit changes) with precision, not force. Here's a specific plan: - **Assess Your Battlefield:** Like Taizu scanning the Five Dynasties mess, map your current chaos. Bullet points: List three "kingdoms" draining you (e.g., toxic job, cluttered home, neglected health). For each, note threats (stress, disorganization) and opportunities (new skills, decluttering apps).

- **Orchestrate Your Mutiny:** Don't wait for a hangover surprise; stage a calculated shift. Bullet points: Choose one area; gather "allies" (friends, apps, books). Set a "Chenqiao moment" – a deadline (e.g., apply for that promotion by week's end). Feign reluctance if needed – tell yourself "I'm not ready," then do it anyway for that dramatic flair. - **Consolidate with Wine (or Wisdom):** Post-"coup," secure gains like Taizu's banquet. Bullet points: Reward supporters (thank mentors); demote "generals" (bad habits) gently – swap scrolling for reading. Centralize control: Daily rituals (morning journal) to prevent backsliding. - **Expand and Innovate:** Taizu unified south first; grow your empire incrementally. Bullet points: Tackle small wins (cook healthy meals thrice weekly); innovate (try a new hobby like Song inventors). Track progress in a "dynasty diary" – note inventions (personal hacks) and alliances. Follow this four-step plan weekly: Assess Sunday, mutiny Monday-Wednesday, consolidate Thursday-Friday, expand Saturday. In months, you'll build your "Song era" – prosperous, innovative, and hilariously unstoppable. Who knew ancient history could be your life coach?