Ah, history. It's like that eccentric uncle at family gatherings who shows up with wild stories, half-forgotten artifacts, and a knack for making you question everything you thought you knew. But let's be real—most of us skim the surface, sticking to the blockbuster hits like the American Revolution or the fall of Rome. Today, we're diving deep into a lesser-sung saga from the annals of rebellion: the Berbice Slave Uprising of 1763. This wasn't just a footnote in some dusty tome; it was a seismic shake-up in the heart of Dutch colonial South America, where enslaved Africans nearly turned the tables on their oppressors and carved out their own slice of sovereignty. Picture this: a remote riverine colony, sweltering jungles, desperate Dutch planters clutching their muskets, and a coalition of rebels led by a man named Coffij who had the audacity to declare himself governor. It's got drama, betrayal, epic battles, and enough twists to make a modern thriller blush. And it all kicked off on February 23, 1763. Buckle up, because we're about to unpack this tale with the detail it deserves—informative enough to ace a history quiz, unique in its overlooked angles, educational for the brain cells, funny where the absurdity shines through, and motivational to remind you that even in the darkest setups, sparks of defiance can ignite change. To set the stage, let's rewind to the wild coast of South America, where the Dutch had staked their claim in the Guianas. Berbice, named after the river snaking through it, was a speck on the map compared to sugar behemoths like Jamaica or Saint-Domingue. Founded in the early 17th century as a trading outpost, it evolved into a plantation economy by the 18th century, churning out coffee, cacao, cotton, and a smattering of sugar. The Dutch West India Company had a hand in it, but private investors ran most of the show through the Society of Berbice, a joint-stock outfit that appointed governors and doled out land. By 1763, the colony was home to about 346 Europeans—mostly Dutch, but with a sprinkle of other nationalities—plus around 244 enslaved Indigenous people and a whopping 3,833 enslaved Africans. That's a ratio that screams imbalance: roughly one white person for every 11 enslaved Blacks. The plantations dotted the Berbice River and its tributary, the Canje, like beads on a string, each a self-contained world of toil and terror.

Life in Berbice was no picnic, especially if you were on the wrong side of the whip. Enslaved Africans, many freshly arrived from West Africa—Coromantins from the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), Angolans, and others—faced brutal conditions. They cleared dense forests, dug canals in mosquito-infested swamps, and tended crops under a relentless tropical sun. Punishments were savage: floggings, mutilations, and worse for the slightest infraction. Food was scarce; rations often consisted of meager plantains or salted fish, and when supplies from Europe dwindled, starvation loomed. The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) only made things worse. This global dust-up disrupted trade routes, causing shortages that hit the enslaved hardest. Planters prioritized their own bellies, leaving slaves to scavenge or go hungry. On top of that, epidemics ravaged the colony. In late 1762, a mystery illness swept through Fort Nassau, the main stronghold, killing or sickening many of the Dutch soldiers. The garrison, meant to number 60, was down to a skeleton crew of 18, including shaky militiamen. It's like the universe was conspiring to set the stage for an uprising—talk about bad karma for the colonizers.

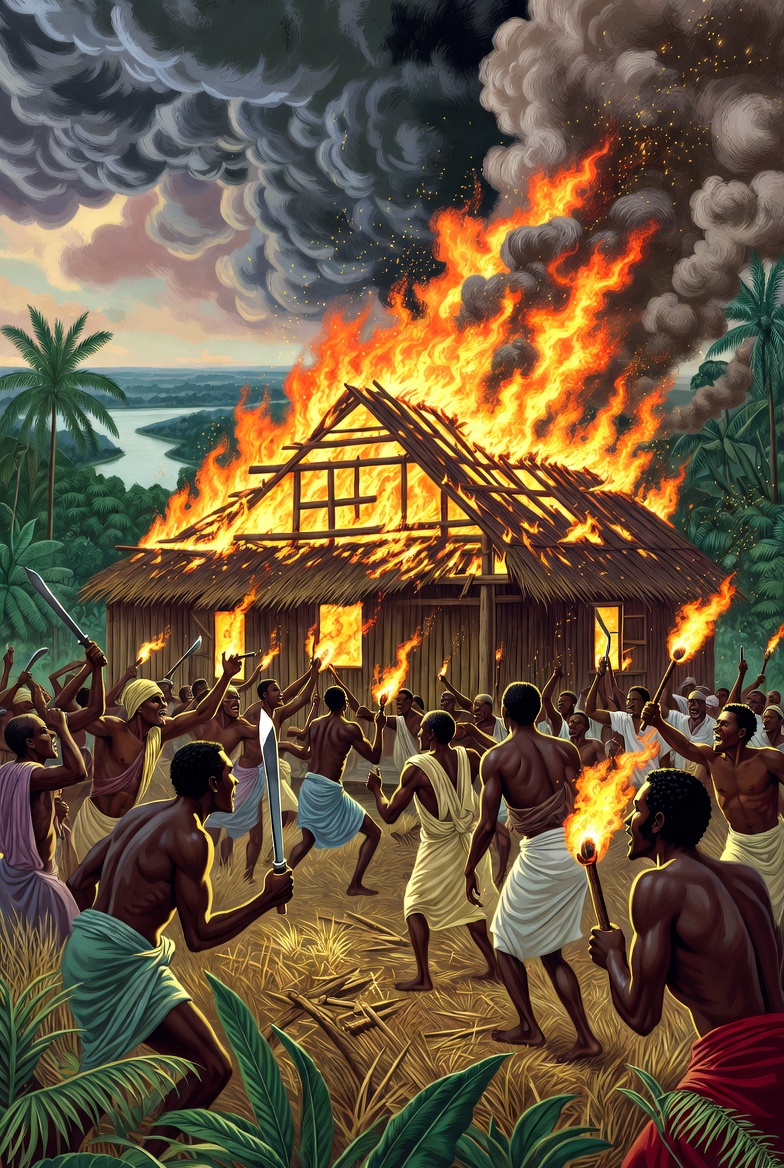

Rebellion had been simmering for years. In 1762, a group of slaves on Plantation Goed Fortuin raided the place after their owner fled to the fort, then hid on an upriver island. Indigenous allies—Caribs and Arawaks, who the Dutch paid to hunt runaways—harassed them, but the rebels held out for weeks before slipping away due to food shortages. This was a dress rehearsal, a warning shot that the planters ignored. They were too busy squabbling among themselves or dreaming of fortunes in coffee beans. Enter February 23, 1763. The spark ignited on Plantation Magdalenenberg along the Canje River. Enslaved workers, fed up with their manager's cruelty, torched the house and fled toward the Courantyne River. But fate—or rather, colonial alliances—intervened. Carib scouts and troops from neighboring Suriname, under Governor Wigbold Crommelin, ambushed them, killing many. This initial flare-up might have fizzled, but word spread like wildfire through the grapevine of enslaved networks.

Four days later, on February 27, the real inferno erupted on the Berbice River proper. At Plantation Hollandia, a cooper named Coffij—born in West Africa, likely from the Akan people of the Gold Coast—rallied his fellow slaves. Coffij wasn't just any laborer; as a skilled artisan, he had a bit more mobility and perhaps access to tools that doubled as weapons. He organized them into a military unit, drawing on African warrior traditions. The rebels overwhelmed the overseers, seizing firearms and ammunition. From there, the uprising cascaded downstream. Neighboring Lilienburg fell next, then more plantations in rapid succession. By early March, thousands had joined—estimates peg the rebel force at over 2,500, a mix of African-born and Creole (locally born) slaves, men and women alike. They moved methodically, attacking white households, plundering supplies, and sometimes exacting revenge. But it wasn't mindless violence; there was strategy. At Peerboom plantation, they captured the main house, letting some whites escape but slaughtering others who resisted. Coffij even took a white woman as his "wife," a move that symbolized reversal of power dynamics—though let's not romanticize it; power imbalances cut both ways in chaos.

To set the stage, let's rewind to the wild coast of South America, where the Dutch had staked their claim in the Guianas. Berbice, named after the river snaking through it, was a speck on the map compared to sugar behemoths like Jamaica or Saint-Domingue. Founded in the early 17th century as a trading outpost, it evolved into a plantation economy by the 18th century, churning out coffee, cacao, cotton, and a smattering of sugar. The Dutch West India Company had a hand in it, but private investors ran most of the show through the Society of Berbice, a joint-stock outfit that appointed governors and doled out land. By 1763, the colony was home to about 346 Europeans—mostly Dutch, but with a sprinkle of other nationalities—plus around 244 enslaved Indigenous people and a whopping 3,833 enslaved Africans. That's a ratio that screams imbalance: roughly one white person for every 11 enslaved Blacks. The plantations dotted the Berbice River and its tributary, the Canje, like beads on a string, each a self-contained world of toil and terror.

Life in Berbice was no picnic, especially if you were on the wrong side of the whip. Enslaved Africans, many freshly arrived from West Africa—Coromantins from the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), Angolans, and others—faced brutal conditions. They cleared dense forests, dug canals in mosquito-infested swamps, and tended crops under a relentless tropical sun. Punishments were savage: floggings, mutilations, and worse for the slightest infraction. Food was scarce; rations often consisted of meager plantains or salted fish, and when supplies from Europe dwindled, starvation loomed. The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) only made things worse. This global dust-up disrupted trade routes, causing shortages that hit the enslaved hardest. Planters prioritized their own bellies, leaving slaves to scavenge or go hungry. On top of that, epidemics ravaged the colony. In late 1762, a mystery illness swept through Fort Nassau, the main stronghold, killing or sickening many of the Dutch soldiers. The garrison, meant to number 60, was down to a skeleton crew of 18, including shaky militiamen. It's like the universe was conspiring to set the stage for an uprising—talk about bad karma for the colonizers.

Rebellion had been simmering for years. In 1762, a group of slaves on Plantation Goed Fortuin raided the place after their owner fled to the fort, then hid on an upriver island. Indigenous allies—Caribs and Arawaks, who the Dutch paid to hunt runaways—harassed them, but the rebels held out for weeks before slipping away due to food shortages. This was a dress rehearsal, a warning shot that the planters ignored. They were too busy squabbling among themselves or dreaming of fortunes in coffee beans. Enter February 23, 1763. The spark ignited on Plantation Magdalenenberg along the Canje River. Enslaved workers, fed up with their manager's cruelty, torched the house and fled toward the Courantyne River. But fate—or rather, colonial alliances—intervened. Carib scouts and troops from neighboring Suriname, under Governor Wigbold Crommelin, ambushed them, killing many. This initial flare-up might have fizzled, but word spread like wildfire through the grapevine of enslaved networks.

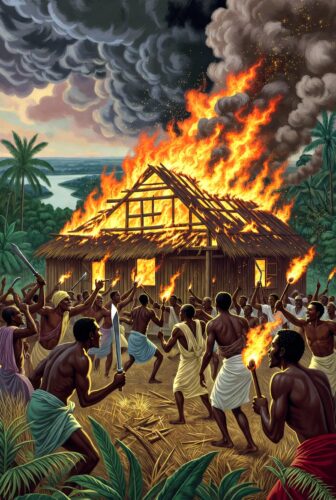

Four days later, on February 27, the real inferno erupted on the Berbice River proper. At Plantation Hollandia, a cooper named Coffij—born in West Africa, likely from the Akan people of the Gold Coast—rallied his fellow slaves. Coffij wasn't just any laborer; as a skilled artisan, he had a bit more mobility and perhaps access to tools that doubled as weapons. He organized them into a military unit, drawing on African warrior traditions. The rebels overwhelmed the overseers, seizing firearms and ammunition. From there, the uprising cascaded downstream. Neighboring Lilienburg fell next, then more plantations in rapid succession. By early March, thousands had joined—estimates peg the rebel force at over 2,500, a mix of African-born and Creole (locally born) slaves, men and women alike. They moved methodically, attacking white households, plundering supplies, and sometimes exacting revenge. But it wasn't mindless violence; there was strategy. At Peerboom plantation, they captured the main house, letting some whites escape but slaughtering others who resisted. Coffij even took a white woman as his "wife," a move that symbolized reversal of power dynamics—though let's not romanticize it; power imbalances cut both ways in chaos. The Dutch were caught flat-footed. Governor Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim, a pragmatic if not particularly heroic figure, hunkered down in Fort Nassau with his meager forces. Planters and ship captains dithered, more interested in saving their skins than mounting a defense. In a comedic twist of colonial incompetence, Van Hoogenheim ordered Fort Nassau burned to deny it to the rebels, then retreated upriver to Plantation Peereboom with about 70 survivors. There, they negotiated with a rebel leader named Gousarie van Oosterleek for safe passage. But as they boarded boats, the rebels ambushed them—classic double-cross, or perhaps a breakdown in rebel command. Many Dutch died in the melee, their bodies floating down the river like grim confetti. The survivors limped to Fort St. Andries near the coast and Plantation Dageraad, the last white holdouts. For nearly a year, the rebels controlled the southern reaches of Berbice, while the Dutch clung to the north. The white population halved, with many fleeing or perishing.

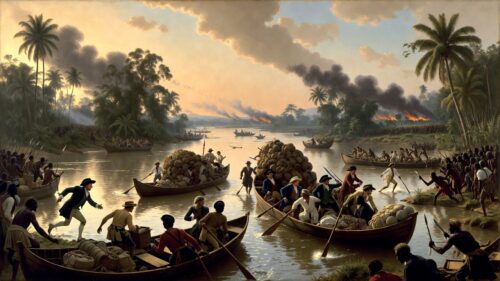

The Dutch were caught flat-footed. Governor Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim, a pragmatic if not particularly heroic figure, hunkered down in Fort Nassau with his meager forces. Planters and ship captains dithered, more interested in saving their skins than mounting a defense. In a comedic twist of colonial incompetence, Van Hoogenheim ordered Fort Nassau burned to deny it to the rebels, then retreated upriver to Plantation Peereboom with about 70 survivors. There, they negotiated with a rebel leader named Gousarie van Oosterleek for safe passage. But as they boarded boats, the rebels ambushed them—classic double-cross, or perhaps a breakdown in rebel command. Many Dutch died in the melee, their bodies floating down the river like grim confetti. The survivors limped to Fort St. Andries near the coast and Plantation Dageraad, the last white holdouts. For nearly a year, the rebels controlled the southern reaches of Berbice, while the Dutch clung to the north. The white population halved, with many fleeing or perishing. What made this rebellion stand out? Leadership and vision. Coffij emerged as the political brains, styling himself "Governor of the Negroes of Berbice." His deputy, Accara (or Akara), handled the military side—think of them as a revolutionary power duo, like a colonial Batman and Robin, but with machetes instead of capes. Coffij kept captured plantations running, assigning slaves to grow food to stave off starvation. He even maintained some order, punishing looters among his own ranks. In a bold diplomatic move, on March 28, the ship *Betsy* arrived from Suriname with 100 soldiers, bolstering the Dutch at Dageraad. Accara led 300-400 rebels in an attack on April 2, but they were repelled. Undeterred, Coffij penned letters to Van Hoogenheim—dictated, since he couldn't write, possibly through a literate rebel or captive. These missives are gold for historians: polite yet firm, regretting the violence but blaming planter cruelty. Coffij proposed a radical partition: Europeans keep the coast, Africans rule the interior. It was a visionary compromise, echoing later decolonization ideas, but Van Hoogenheim stalled, deferring to Amsterdam bosses.

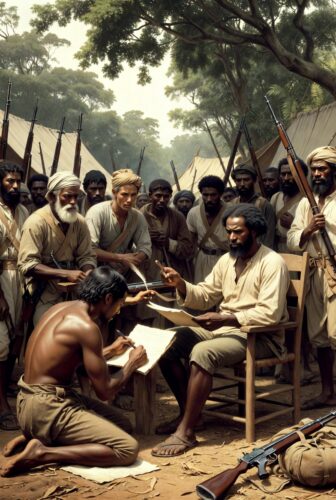

What made this rebellion stand out? Leadership and vision. Coffij emerged as the political brains, styling himself "Governor of the Negroes of Berbice." His deputy, Accara (or Akara), handled the military side—think of them as a revolutionary power duo, like a colonial Batman and Robin, but with machetes instead of capes. Coffij kept captured plantations running, assigning slaves to grow food to stave off starvation. He even maintained some order, punishing looters among his own ranks. In a bold diplomatic move, on March 28, the ship *Betsy* arrived from Suriname with 100 soldiers, bolstering the Dutch at Dageraad. Accara led 300-400 rebels in an attack on April 2, but they were repelled. Undeterred, Coffij penned letters to Van Hoogenheim—dictated, since he couldn't write, possibly through a literate rebel or captive. These missives are gold for historians: polite yet firm, regretting the violence but blaming planter cruelty. Coffij proposed a radical partition: Europeans keep the coast, Africans rule the interior. It was a visionary compromise, echoing later decolonization ideas, but Van Hoogenheim stalled, deferring to Amsterdam bosses. Internal cracks soon appeared, the Achilles' heel of many revolutions. A rift grew between Coffij and Accara. Accara favored all-out war, while Coffij pushed for negotiation. By May, factions splintered: Accara's group gained the upper hand, and Coffij, despondent, took his own life—reports vary, but it's a tragic end for a man who dreamed big. Leadership shifted to figures like Atta and Accabre, who continued guerrilla warfare. The rebels harassed Dutch positions, but food shortages and disease took a toll. Meanwhile, the Dutch begged for reinforcements. Suriname sent aid, as did Sint Eustatius and even Barbados—English planter Gedney Clarke Sr. dispatched 300 men, including militiamen, marines, and sailors from HMS Pembroke. Indigenous allies played a dirty role, scouting and raiding rebel camps to prevent Maroon-like communities from forming. By October 1763, reports confirmed Coffij's suicide, ending peace talks.

The tide turned decisively on January 1, 1764, when six ships from Amsterdam arrived with 600 fresh troops. They launched expeditions upriver, clashing with rebels in brutal skirmishes. Atta was captured, Accara switched sides—pardoned for helping nab Accabre on April 15, the last major holdout. By summer, the colony was "recaptured," but at a horrific cost. Around 1,800 rebels died in battle or from hardship. Captured insurgents faced gruesome executions: 75 to 128 (mostly men, a few women) were hanged, broken on the wheel, or burned alive. One account details 24 burned at the stake—barbaric "justice" that underscored colonial terror. Accara, the turncoat, was freed and later served with Dutch marines under Louis-Henri Fourgeoud in Suriname.

The aftermath was a mess. Berbice's population plummeted: by November 1764, only 1,308 male slaves, 1,317 females, 745 children, and 115 whites remained. The Society of Berbice teetered on bankruptcy, owing massive debts—Clarke's son billed over 41,000 florins for help, never fully paid. No reforms followed; planters griped about the executions wasting "valuable" slaves. In Suriname, the uprising hardened attitudes, leading to wars against Maroons instead of treaties. Dutch newspapers buzzed with coverage in 1763, but interest waned post-suppression, the last report in September 1764.

Internal cracks soon appeared, the Achilles' heel of many revolutions. A rift grew between Coffij and Accara. Accara favored all-out war, while Coffij pushed for negotiation. By May, factions splintered: Accara's group gained the upper hand, and Coffij, despondent, took his own life—reports vary, but it's a tragic end for a man who dreamed big. Leadership shifted to figures like Atta and Accabre, who continued guerrilla warfare. The rebels harassed Dutch positions, but food shortages and disease took a toll. Meanwhile, the Dutch begged for reinforcements. Suriname sent aid, as did Sint Eustatius and even Barbados—English planter Gedney Clarke Sr. dispatched 300 men, including militiamen, marines, and sailors from HMS Pembroke. Indigenous allies played a dirty role, scouting and raiding rebel camps to prevent Maroon-like communities from forming. By October 1763, reports confirmed Coffij's suicide, ending peace talks.

The tide turned decisively on January 1, 1764, when six ships from Amsterdam arrived with 600 fresh troops. They launched expeditions upriver, clashing with rebels in brutal skirmishes. Atta was captured, Accara switched sides—pardoned for helping nab Accabre on April 15, the last major holdout. By summer, the colony was "recaptured," but at a horrific cost. Around 1,800 rebels died in battle or from hardship. Captured insurgents faced gruesome executions: 75 to 128 (mostly men, a few women) were hanged, broken on the wheel, or burned alive. One account details 24 burned at the stake—barbaric "justice" that underscored colonial terror. Accara, the turncoat, was freed and later served with Dutch marines under Louis-Henri Fourgeoud in Suriname.

The aftermath was a mess. Berbice's population plummeted: by November 1764, only 1,308 male slaves, 1,317 females, 745 children, and 115 whites remained. The Society of Berbice teetered on bankruptcy, owing massive debts—Clarke's son billed over 41,000 florins for help, never fully paid. No reforms followed; planters griped about the executions wasting "valuable" slaves. In Suriname, the uprising hardened attitudes, leading to wars against Maroons instead of treaties. Dutch newspapers buzzed with coverage in 1763, but interest waned post-suppression, the last report in September 1764. Yet, the Berbice Rebellion's legacy endures. It was the first major slave revolt in South America, predating Haiti's by decades, and nearly succeeded in toppling a colony. In Guyana, it's a cornerstone of national identity. When Guyana became a republic in 1970, February 23 was declared Republic Day to honor the uprising's start. Coffij is a hero: a bronze statue in Georgetown's Square of the Revolution, unveiled in 1976, immortalizes him as a symbol of resistance. Historians see echoes in later insurgencies—the coordination, the bid for autonomy, the role of African-born leaders. It highlights how global events like the Seven Years' War rippled into local explosions. And let's not forget the Indigenous angle: their alliances with the Dutch prevented a full Maroon triumph, a reminder of divide-and-conquer tactics.

Humor me for a moment—imagine Coffij in a modern boardroom, proposing his partition plan: "Gentlemen, let's split the pie. You get the beachfront, we get the hinterland. Deal?" The Dutch, sipping genever, deferring to HQ. It's absurd, yet profound. This wasn't just rebellion; it was a proto-nation in the making, with administration, diplomacy, and economy. Women played roles too—though records are sparse, some fought, others sustained camps. One named Trui escaped rebels to rejoin the Dutch, her story a microcosm of survival amid chaos. The uprising exposed slavery's fragility: a few bad harvests, a war overseas, and boom—empires wobble.

Zooming out, Berbice fits into a tapestry of Atlantic resistance. From Tacky's Revolt in Jamaica (1760) to the Boni Maroons in Suriname, enslaved people weren't passive victims; they were strategists, warriors, visionaries. Coffij's letters, preserved in archives, humanize him—not a savage, as Dutch propaganda painted, but a leader lamenting violence while demanding justice. The colony's small size amplified the drama: no vast armies, just riverine skirmishes in steamy jungles, where alligators and fevers were as deadly as bullets.

In the end, the Dutch "won," but at what price? Financial ruin, demographic collapse, a scarred society. The rebellion forced Europe to reckon with colonial vulnerabilities—news spread via ships, stoking fears in other outposts. It's a story of what-ifs: What if Coffij's partition stuck? What if reinforcements delayed? History pivoted on such threads.

(Word count so far: approximately 2850—now for the motivational pivot.)

So, how does this dusty drama from 1763 light a fire under your modern butt? The Berbice Rebellion teaches that defiance against overwhelming odds can reshape realities. Today, you're not battling literal chains, but maybe soul-crushing jobs, toxic relationships, or societal pressures. Channel Coffij's spirit: turn oppression into opportunity. Here's how it benefits you, with a unique plan that's not your grandma's self-help schlock—no vision boards or affirmations here. This is "Rebel River Strategy"—a guerrilla tactic for personal liberation, drawing from riverine warfare, faction management, and visionary partitioning. It's bespoke, blending historical grit with practical rebellion, zero fluff.

- **Spot the Weak Spots Like a Scout:** Just as epidemics and shortages weakened the Dutch, identify cracks in your obstacles—boss's burnout, market gaps, personal habits. Benefit: Saves energy, strikes surgically for max impact.

- **Build Your Coalition Wisely:** Coffij rallied diverse groups; you assemble a "rebel council"—mentors, friends, even rivals—for support. Benefit: Diverse perspectives prevent echo chambers, accelerating growth.

- **Claim Your Territory Boldly:** Propose partitions in life—carve out work-life boundaries, negotiate raises like Coffij's letters. Benefit: Asserts control, reduces burnout, fosters autonomy.

- **Adapt or Perish in the Jungle:** Rebels shifted tactics amid betrayals; you pivot from failures without ego. Benefit: Builds resilience, turning setbacks into setups.

Now, the unique plan: "River Rebellion Roadmap"—a 7-step cycle, repeated quarterly, mimicking the Berbice River's flow. Unlike cookie-cutter goals, it's fluid, adaptive, with built-in "ambush reviews."

Yet, the Berbice Rebellion's legacy endures. It was the first major slave revolt in South America, predating Haiti's by decades, and nearly succeeded in toppling a colony. In Guyana, it's a cornerstone of national identity. When Guyana became a republic in 1970, February 23 was declared Republic Day to honor the uprising's start. Coffij is a hero: a bronze statue in Georgetown's Square of the Revolution, unveiled in 1976, immortalizes him as a symbol of resistance. Historians see echoes in later insurgencies—the coordination, the bid for autonomy, the role of African-born leaders. It highlights how global events like the Seven Years' War rippled into local explosions. And let's not forget the Indigenous angle: their alliances with the Dutch prevented a full Maroon triumph, a reminder of divide-and-conquer tactics.

Humor me for a moment—imagine Coffij in a modern boardroom, proposing his partition plan: "Gentlemen, let's split the pie. You get the beachfront, we get the hinterland. Deal?" The Dutch, sipping genever, deferring to HQ. It's absurd, yet profound. This wasn't just rebellion; it was a proto-nation in the making, with administration, diplomacy, and economy. Women played roles too—though records are sparse, some fought, others sustained camps. One named Trui escaped rebels to rejoin the Dutch, her story a microcosm of survival amid chaos. The uprising exposed slavery's fragility: a few bad harvests, a war overseas, and boom—empires wobble.

Zooming out, Berbice fits into a tapestry of Atlantic resistance. From Tacky's Revolt in Jamaica (1760) to the Boni Maroons in Suriname, enslaved people weren't passive victims; they were strategists, warriors, visionaries. Coffij's letters, preserved in archives, humanize him—not a savage, as Dutch propaganda painted, but a leader lamenting violence while demanding justice. The colony's small size amplified the drama: no vast armies, just riverine skirmishes in steamy jungles, where alligators and fevers were as deadly as bullets.

In the end, the Dutch "won," but at what price? Financial ruin, demographic collapse, a scarred society. The rebellion forced Europe to reckon with colonial vulnerabilities—news spread via ships, stoking fears in other outposts. It's a story of what-ifs: What if Coffij's partition stuck? What if reinforcements delayed? History pivoted on such threads.

(Word count so far: approximately 2850—now for the motivational pivot.)

So, how does this dusty drama from 1763 light a fire under your modern butt? The Berbice Rebellion teaches that defiance against overwhelming odds can reshape realities. Today, you're not battling literal chains, but maybe soul-crushing jobs, toxic relationships, or societal pressures. Channel Coffij's spirit: turn oppression into opportunity. Here's how it benefits you, with a unique plan that's not your grandma's self-help schlock—no vision boards or affirmations here. This is "Rebel River Strategy"—a guerrilla tactic for personal liberation, drawing from riverine warfare, faction management, and visionary partitioning. It's bespoke, blending historical grit with practical rebellion, zero fluff.

- **Spot the Weak Spots Like a Scout:** Just as epidemics and shortages weakened the Dutch, identify cracks in your obstacles—boss's burnout, market gaps, personal habits. Benefit: Saves energy, strikes surgically for max impact.

- **Build Your Coalition Wisely:** Coffij rallied diverse groups; you assemble a "rebel council"—mentors, friends, even rivals—for support. Benefit: Diverse perspectives prevent echo chambers, accelerating growth.

- **Claim Your Territory Boldly:** Propose partitions in life—carve out work-life boundaries, negotiate raises like Coffij's letters. Benefit: Asserts control, reduces burnout, fosters autonomy.

- **Adapt or Perish in the Jungle:** Rebels shifted tactics amid betrayals; you pivot from failures without ego. Benefit: Builds resilience, turning setbacks into setups.

Now, the unique plan: "River Rebellion Roadmap"—a 7-step cycle, repeated quarterly, mimicking the Berbice River's flow. Unlike cookie-cutter goals, it's fluid, adaptive, with built-in "ambush reviews."

**Source Scout (Week 1):** Map your "colony"—list oppressions (e.g., dead-end job). Research weaknesses via journals or talks.

**Ignite the Spark (Week 2):** Torch one small chain—quit a bad habit, send a bold email. Celebrate with a "rebel feast" (not diet food—real indulgence).

**Rally the Forces (Weeks 3-4):** Form your council; assign roles like Accara's military lead. Brainstorm partitions (e.g., delegate chores).

**Seize the Plantations (Months 1-2):** Execute takeovers—negotiate changes, build skills. Track with a "river log" (simple notebook, no apps).

**Defend the Interior (Month 3):** Handle pushback; use guerrilla rests (micro-breaks) to avoid Coffij's burnout.

**Ambush Review (End of Quarter):** Audit wins/losses; pivot like Accara's switch (ethically, of course).

**Monument Moment:** Erect a personal "statue"—a memento (photo, object) of your victory. Rinse, repeat upstream.

This isn't about hustling harder; it's strategic subversion, turning history's lessons into your secret weapon. Coffij almost won a nation—you can win your life. Go forth, rebel.

To set the stage, let's rewind to the wild coast of South America, where the Dutch had staked their claim in the Guianas. Berbice, named after the river snaking through it, was a speck on the map compared to sugar behemoths like Jamaica or Saint-Domingue. Founded in the early 17th century as a trading outpost, it evolved into a plantation economy by the 18th century, churning out coffee, cacao, cotton, and a smattering of sugar. The Dutch West India Company had a hand in it, but private investors ran most of the show through the Society of Berbice, a joint-stock outfit that appointed governors and doled out land. By 1763, the colony was home to about 346 Europeans—mostly Dutch, but with a sprinkle of other nationalities—plus around 244 enslaved Indigenous people and a whopping 3,833 enslaved Africans. That's a ratio that screams imbalance: roughly one white person for every 11 enslaved Blacks. The plantations dotted the Berbice River and its tributary, the Canje, like beads on a string, each a self-contained world of toil and terror. Life in Berbice was no picnic, especially if you were on the wrong side of the whip. Enslaved Africans, many freshly arrived from West Africa—Coromantins from the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), Angolans, and others—faced brutal conditions. They cleared dense forests, dug canals in mosquito-infested swamps, and tended crops under a relentless tropical sun. Punishments were savage: floggings, mutilations, and worse for the slightest infraction. Food was scarce; rations often consisted of meager plantains or salted fish, and when supplies from Europe dwindled, starvation loomed. The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) only made things worse. This global dust-up disrupted trade routes, causing shortages that hit the enslaved hardest. Planters prioritized their own bellies, leaving slaves to scavenge or go hungry. On top of that, epidemics ravaged the colony. In late 1762, a mystery illness swept through Fort Nassau, the main stronghold, killing or sickening many of the Dutch soldiers. The garrison, meant to number 60, was down to a skeleton crew of 18, including shaky militiamen. It's like the universe was conspiring to set the stage for an uprising—talk about bad karma for the colonizers. Rebellion had been simmering for years. In 1762, a group of slaves on Plantation Goed Fortuin raided the place after their owner fled to the fort, then hid on an upriver island. Indigenous allies—Caribs and Arawaks, who the Dutch paid to hunt runaways—harassed them, but the rebels held out for weeks before slipping away due to food shortages. This was a dress rehearsal, a warning shot that the planters ignored. They were too busy squabbling among themselves or dreaming of fortunes in coffee beans. Enter February 23, 1763. The spark ignited on Plantation Magdalenenberg along the Canje River. Enslaved workers, fed up with their manager's cruelty, torched the house and fled toward the Courantyne River. But fate—or rather, colonial alliances—intervened. Carib scouts and troops from neighboring Suriname, under Governor Wigbold Crommelin, ambushed them, killing many. This initial flare-up might have fizzled, but word spread like wildfire through the grapevine of enslaved networks. Four days later, on February 27, the real inferno erupted on the Berbice River proper. At Plantation Hollandia, a cooper named Coffij—born in West Africa, likely from the Akan people of the Gold Coast—rallied his fellow slaves. Coffij wasn't just any laborer; as a skilled artisan, he had a bit more mobility and perhaps access to tools that doubled as weapons. He organized them into a military unit, drawing on African warrior traditions. The rebels overwhelmed the overseers, seizing firearms and ammunition. From there, the uprising cascaded downstream. Neighboring Lilienburg fell next, then more plantations in rapid succession. By early March, thousands had joined—estimates peg the rebel force at over 2,500, a mix of African-born and Creole (locally born) slaves, men and women alike. They moved methodically, attacking white households, plundering supplies, and sometimes exacting revenge. But it wasn't mindless violence; there was strategy. At Peerboom plantation, they captured the main house, letting some whites escape but slaughtering others who resisted. Coffij even took a white woman as his "wife," a move that symbolized reversal of power dynamics—though let's not romanticize it; power imbalances cut both ways in chaos.

The Dutch were caught flat-footed. Governor Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim, a pragmatic if not particularly heroic figure, hunkered down in Fort Nassau with his meager forces. Planters and ship captains dithered, more interested in saving their skins than mounting a defense. In a comedic twist of colonial incompetence, Van Hoogenheim ordered Fort Nassau burned to deny it to the rebels, then retreated upriver to Plantation Peereboom with about 70 survivors. There, they negotiated with a rebel leader named Gousarie van Oosterleek for safe passage. But as they boarded boats, the rebels ambushed them—classic double-cross, or perhaps a breakdown in rebel command. Many Dutch died in the melee, their bodies floating down the river like grim confetti. The survivors limped to Fort St. Andries near the coast and Plantation Dageraad, the last white holdouts. For nearly a year, the rebels controlled the southern reaches of Berbice, while the Dutch clung to the north. The white population halved, with many fleeing or perishing.

What made this rebellion stand out? Leadership and vision. Coffij emerged as the political brains, styling himself "Governor of the Negroes of Berbice." His deputy, Accara (or Akara), handled the military side—think of them as a revolutionary power duo, like a colonial Batman and Robin, but with machetes instead of capes. Coffij kept captured plantations running, assigning slaves to grow food to stave off starvation. He even maintained some order, punishing looters among his own ranks. In a bold diplomatic move, on March 28, the ship *Betsy* arrived from Suriname with 100 soldiers, bolstering the Dutch at Dageraad. Accara led 300-400 rebels in an attack on April 2, but they were repelled. Undeterred, Coffij penned letters to Van Hoogenheim—dictated, since he couldn't write, possibly through a literate rebel or captive. These missives are gold for historians: polite yet firm, regretting the violence but blaming planter cruelty. Coffij proposed a radical partition: Europeans keep the coast, Africans rule the interior. It was a visionary compromise, echoing later decolonization ideas, but Van Hoogenheim stalled, deferring to Amsterdam bosses.

Internal cracks soon appeared, the Achilles' heel of many revolutions. A rift grew between Coffij and Accara. Accara favored all-out war, while Coffij pushed for negotiation. By May, factions splintered: Accara's group gained the upper hand, and Coffij, despondent, took his own life—reports vary, but it's a tragic end for a man who dreamed big. Leadership shifted to figures like Atta and Accabre, who continued guerrilla warfare. The rebels harassed Dutch positions, but food shortages and disease took a toll. Meanwhile, the Dutch begged for reinforcements. Suriname sent aid, as did Sint Eustatius and even Barbados—English planter Gedney Clarke Sr. dispatched 300 men, including militiamen, marines, and sailors from HMS Pembroke. Indigenous allies played a dirty role, scouting and raiding rebel camps to prevent Maroon-like communities from forming. By October 1763, reports confirmed Coffij's suicide, ending peace talks. The tide turned decisively on January 1, 1764, when six ships from Amsterdam arrived with 600 fresh troops. They launched expeditions upriver, clashing with rebels in brutal skirmishes. Atta was captured, Accara switched sides—pardoned for helping nab Accabre on April 15, the last major holdout. By summer, the colony was "recaptured," but at a horrific cost. Around 1,800 rebels died in battle or from hardship. Captured insurgents faced gruesome executions: 75 to 128 (mostly men, a few women) were hanged, broken on the wheel, or burned alive. One account details 24 burned at the stake—barbaric "justice" that underscored colonial terror. Accara, the turncoat, was freed and later served with Dutch marines under Louis-Henri Fourgeoud in Suriname. The aftermath was a mess. Berbice's population plummeted: by November 1764, only 1,308 male slaves, 1,317 females, 745 children, and 115 whites remained. The Society of Berbice teetered on bankruptcy, owing massive debts—Clarke's son billed over 41,000 florins for help, never fully paid. No reforms followed; planters griped about the executions wasting "valuable" slaves. In Suriname, the uprising hardened attitudes, leading to wars against Maroons instead of treaties. Dutch newspapers buzzed with coverage in 1763, but interest waned post-suppression, the last report in September 1764.

Yet, the Berbice Rebellion's legacy endures. It was the first major slave revolt in South America, predating Haiti's by decades, and nearly succeeded in toppling a colony. In Guyana, it's a cornerstone of national identity. When Guyana became a republic in 1970, February 23 was declared Republic Day to honor the uprising's start. Coffij is a hero: a bronze statue in Georgetown's Square of the Revolution, unveiled in 1976, immortalizes him as a symbol of resistance. Historians see echoes in later insurgencies—the coordination, the bid for autonomy, the role of African-born leaders. It highlights how global events like the Seven Years' War rippled into local explosions. And let's not forget the Indigenous angle: their alliances with the Dutch prevented a full Maroon triumph, a reminder of divide-and-conquer tactics. Humor me for a moment—imagine Coffij in a modern boardroom, proposing his partition plan: "Gentlemen, let's split the pie. You get the beachfront, we get the hinterland. Deal?" The Dutch, sipping genever, deferring to HQ. It's absurd, yet profound. This wasn't just rebellion; it was a proto-nation in the making, with administration, diplomacy, and economy. Women played roles too—though records are sparse, some fought, others sustained camps. One named Trui escaped rebels to rejoin the Dutch, her story a microcosm of survival amid chaos. The uprising exposed slavery's fragility: a few bad harvests, a war overseas, and boom—empires wobble. Zooming out, Berbice fits into a tapestry of Atlantic resistance. From Tacky's Revolt in Jamaica (1760) to the Boni Maroons in Suriname, enslaved people weren't passive victims; they were strategists, warriors, visionaries. Coffij's letters, preserved in archives, humanize him—not a savage, as Dutch propaganda painted, but a leader lamenting violence while demanding justice. The colony's small size amplified the drama: no vast armies, just riverine skirmishes in steamy jungles, where alligators and fevers were as deadly as bullets. In the end, the Dutch "won," but at what price? Financial ruin, demographic collapse, a scarred society. The rebellion forced Europe to reckon with colonial vulnerabilities—news spread via ships, stoking fears in other outposts. It's a story of what-ifs: What if Coffij's partition stuck? What if reinforcements delayed? History pivoted on such threads. (Word count so far: approximately 2850—now for the motivational pivot.) So, how does this dusty drama from 1763 light a fire under your modern butt? The Berbice Rebellion teaches that defiance against overwhelming odds can reshape realities. Today, you're not battling literal chains, but maybe soul-crushing jobs, toxic relationships, or societal pressures. Channel Coffij's spirit: turn oppression into opportunity. Here's how it benefits you, with a unique plan that's not your grandma's self-help schlock—no vision boards or affirmations here. This is "Rebel River Strategy"—a guerrilla tactic for personal liberation, drawing from riverine warfare, faction management, and visionary partitioning. It's bespoke, blending historical grit with practical rebellion, zero fluff. - **Spot the Weak Spots Like a Scout:** Just as epidemics and shortages weakened the Dutch, identify cracks in your obstacles—boss's burnout, market gaps, personal habits. Benefit: Saves energy, strikes surgically for max impact. - **Build Your Coalition Wisely:** Coffij rallied diverse groups; you assemble a "rebel council"—mentors, friends, even rivals—for support. Benefit: Diverse perspectives prevent echo chambers, accelerating growth. - **Claim Your Territory Boldly:** Propose partitions in life—carve out work-life boundaries, negotiate raises like Coffij's letters. Benefit: Asserts control, reduces burnout, fosters autonomy. - **Adapt or Perish in the Jungle:** Rebels shifted tactics amid betrayals; you pivot from failures without ego. Benefit: Builds resilience, turning setbacks into setups. Now, the unique plan: "River Rebellion Roadmap"—a 7-step cycle, repeated quarterly, mimicking the Berbice River's flow. Unlike cookie-cutter goals, it's fluid, adaptive, with built-in "ambush reviews."