Imagine this: It's the late 15th century, and you're a cash-strapped king with a daughter to marry off. Your kingdom's coffers are emptier than a Viking longship after a bad raid, and the groom's family is tapping their feet, waiting for that promised dowry. What do you do? If you're Christian I of Denmark-Norway-Sweden, you don't sell the family silver—you pawn a couple of far-flung island chains that have been in your realm for centuries. Sounds like a plot from a medieval sitcom, right? But this isn't fiction; it's the hilariously bungled backstory to how Orkney and Shetland, those rugged, wind-swept gems of the North Atlantic, ended up Scottish instead of Scandinavian. And it all culminated on February 20, 1472, when the Scottish Parliament rubber-stamped the deal, turning a temporary loan into a permanent land grab. This tale isn't just about dusty old kings and forgotten treaties—it's a whirlwind of Viking conquests, political intrigue, cultural clashes, and economic face-plants that shaped the map of northern Europe. We'll dive deep into the historical nitty-gritty, uncovering how these islands went from Norse strongholds to Scottish outposts, with plenty of educational detours into archaeology, genetics, and even a dash of royal scandal. Along the way, I'll sprinkle in some humor because, let's face it, watching medieval monarchs fumble their finances is timeless comedy. And at the end? We'll pivot to how this ancient blunder can motivate you today—turning historical hindsight into personal foresight. Buckle up; this is going to be a long, enlightening ride through the misty isles.

Let's start at the beginning, way back when these islands weren't even on most Europeans' maps. Orkney and Shetland, collectively known as the Northern Isles, sit like stubborn sentinels off Scotland's northern tip—Orkney closer to the mainland, a cluster of about 70 islands (20 inhabited), and Shetland farther north, with over 100 islands (15 inhabited). Their history kicks off around 8,800 years ago, when the last ice age glaciers retreated, leaving behind fertile (if chilly) land for hunter-gatherers. Archaeological digs reveal Mesolithic folks chasing seals and birds, but things really heated up in the Neolithic era, around 3500 BC. That's when farming arrived, and these early islanders built some of the most mind-blowing structures in prehistoric Europe.

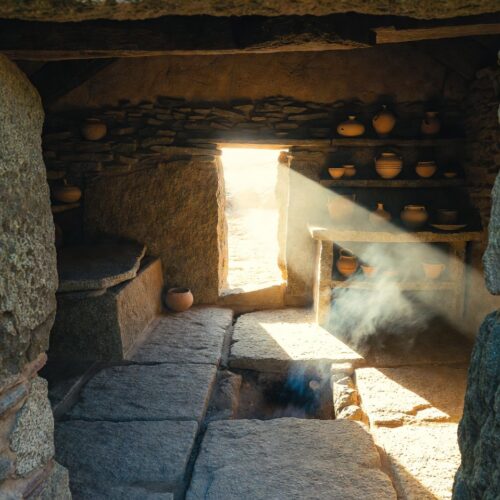

Take Skara Brae on Orkney's Mainland—it's like a Stone Age suburb preserved in sand after a storm buried it around 2500 BC. Excavated in the 1850s, this village of eight connected houses features stone beds, dressers for displaying pottery, and even indoor toilets flushed by streams. Imagine: These people had better plumbing than some medieval castles! Linked to grooved ware pottery, Skara Brae ties into the nearby Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, massive stone circles that Professor Alexander Thom theorized were ancient observatories for tracking lunar cycles. Not far away, Maeshowe is a chambered tomb with Viking graffiti scratched into the walls centuries later—rude runes like "Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes," proving even Norsemen couldn't resist tagging historic sites.

This tale isn't just about dusty old kings and forgotten treaties—it's a whirlwind of Viking conquests, political intrigue, cultural clashes, and economic face-plants that shaped the map of northern Europe. We'll dive deep into the historical nitty-gritty, uncovering how these islands went from Norse strongholds to Scottish outposts, with plenty of educational detours into archaeology, genetics, and even a dash of royal scandal. Along the way, I'll sprinkle in some humor because, let's face it, watching medieval monarchs fumble their finances is timeless comedy. And at the end? We'll pivot to how this ancient blunder can motivate you today—turning historical hindsight into personal foresight. Buckle up; this is going to be a long, enlightening ride through the misty isles.

Let's start at the beginning, way back when these islands weren't even on most Europeans' maps. Orkney and Shetland, collectively known as the Northern Isles, sit like stubborn sentinels off Scotland's northern tip—Orkney closer to the mainland, a cluster of about 70 islands (20 inhabited), and Shetland farther north, with over 100 islands (15 inhabited). Their history kicks off around 8,800 years ago, when the last ice age glaciers retreated, leaving behind fertile (if chilly) land for hunter-gatherers. Archaeological digs reveal Mesolithic folks chasing seals and birds, but things really heated up in the Neolithic era, around 3500 BC. That's when farming arrived, and these early islanders built some of the most mind-blowing structures in prehistoric Europe.

Take Skara Brae on Orkney's Mainland—it's like a Stone Age suburb preserved in sand after a storm buried it around 2500 BC. Excavated in the 1850s, this village of eight connected houses features stone beds, dressers for displaying pottery, and even indoor toilets flushed by streams. Imagine: These people had better plumbing than some medieval castles! Linked to grooved ware pottery, Skara Brae ties into the nearby Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, massive stone circles that Professor Alexander Thom theorized were ancient observatories for tracking lunar cycles. Not far away, Maeshowe is a chambered tomb with Viking graffiti scratched into the walls centuries later—rude runes like "Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes," proving even Norsemen couldn't resist tagging historic sites. Shetland's prehistoric scene is similar but wilder, with sites like Jarlshof spanning 4,000 years of occupation—from Neolithic houses to Iron Age brochs (those iconic round towers) to Viking longhouses. The Broch of Mousa, a 13-meter-high stone tower on a tiny island, is the best-preserved in Scotland, complete with internal staircases and a view that screams "impenetrable fortress." These brochs, built around 100 BC to 100 AD, were likely status symbols for Iron Age chieftains, surrounded by ditches and ramparts. Artifacts include quern-stones for grinding grain, bone combs, and simple pottery, hinting at a society focused on survival in a harsh climate.

By the Pictish era (around 300-900 AD), the islands were home to mysterious symbol stones and roundhouses. The Picts, those enigmatic tattooed warriors described by Romans as "painted people," left behind art like the ogham-inscribed stones on Orkney. Romans knew of the islands as "Orcades," possibly trading there or even briefly administering them as a province after Agricola's fleet circumnavigated Britain in 84 AD. But the real game-changer came with the Vikings in the 8th-9th centuries. Norsemen, fleeing overpopulation and seeking plunder, turned the Northern Isles into a launchpad for raids on Scotland and Ireland.

Picture Harald Hårfagre (Fairhair), the first king to unify Norway around 875 AD. After a messy family feud, he sailed west to quash rebellious Vikings using Orkney as a base. Legend has it he annexed the islands after his son was killed in battle—compensation granted to Ragnvald, Earl of Møre, who then passed the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty. Sigurd expanded south, conquering parts of Scotland, but met a comical end: He beheaded a Scottish chieftain, tied the head to his saddle, and got fatally scratched by the dead man's tooth. Talk about a biting comeback!

Under Norwegian rule, Orkney and Shetland flourished as earldoms. Key jarls included Turf-Einar (d. 910), who avenged his father's death by blood-eagling the culprit (a gruesome ritual of carving an eagle into the back), and Thorfinn the Mighty (d. 1065), who ruled from Dublin to Shetland like a mini-emperor. Christianity trickled in around 995, forced by kings like Olaf Tryggvason, who allegedly baptized the Orcadian earl Sigurd the Stout at swordpoint. Saint Magnus, co-earl from 1106-1117, became a martyr when his cousin Hakon had him axed during a power struggle—his cathedral in Kirkwall, started in 1137, stands as a red sandstone testament to Norse piety.

The islands' Norse identity deepened with the Norn language, a West Norse dialect that evolved into a unique tongue, full of words like "peerie" (small) that still pepper modern Orcadian and Shetlander speech. Genetics back this up: Studies show about 30% of Orkney's male lineages trace to western Norway, with bilateral Scandinavian ancestry around 44% in Shetland. Place names are overwhelmingly Norse—think "kirk" for church or "voe" for inlet. Law followed udal tenure, where land was owned outright without feudal overlords, passed down without written deeds. This allodial system clashed later with Scottish feudalism, leading to centuries of legal headaches.

By the 14th century, Norway's grip weakened. The Black Death ravaged Scandinavia in 1349, killing up to 60% of the population and shifting power to Denmark via the Kalmar Union in 1397, uniting Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under one crown. Orkney and Shetland became peripheral provinces, with earls like Henry Sinclair (d. 1400) juggling loyalties—he's the stuff of legends, allegedly sailing to North America in 1398, beating Columbus by a century (though evidence is shaky, involving dubious maps and Templar conspiracy theories).

Shetland's prehistoric scene is similar but wilder, with sites like Jarlshof spanning 4,000 years of occupation—from Neolithic houses to Iron Age brochs (those iconic round towers) to Viking longhouses. The Broch of Mousa, a 13-meter-high stone tower on a tiny island, is the best-preserved in Scotland, complete with internal staircases and a view that screams "impenetrable fortress." These brochs, built around 100 BC to 100 AD, were likely status symbols for Iron Age chieftains, surrounded by ditches and ramparts. Artifacts include quern-stones for grinding grain, bone combs, and simple pottery, hinting at a society focused on survival in a harsh climate.

By the Pictish era (around 300-900 AD), the islands were home to mysterious symbol stones and roundhouses. The Picts, those enigmatic tattooed warriors described by Romans as "painted people," left behind art like the ogham-inscribed stones on Orkney. Romans knew of the islands as "Orcades," possibly trading there or even briefly administering them as a province after Agricola's fleet circumnavigated Britain in 84 AD. But the real game-changer came with the Vikings in the 8th-9th centuries. Norsemen, fleeing overpopulation and seeking plunder, turned the Northern Isles into a launchpad for raids on Scotland and Ireland.

Picture Harald Hårfagre (Fairhair), the first king to unify Norway around 875 AD. After a messy family feud, he sailed west to quash rebellious Vikings using Orkney as a base. Legend has it he annexed the islands after his son was killed in battle—compensation granted to Ragnvald, Earl of Møre, who then passed the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty. Sigurd expanded south, conquering parts of Scotland, but met a comical end: He beheaded a Scottish chieftain, tied the head to his saddle, and got fatally scratched by the dead man's tooth. Talk about a biting comeback!

Under Norwegian rule, Orkney and Shetland flourished as earldoms. Key jarls included Turf-Einar (d. 910), who avenged his father's death by blood-eagling the culprit (a gruesome ritual of carving an eagle into the back), and Thorfinn the Mighty (d. 1065), who ruled from Dublin to Shetland like a mini-emperor. Christianity trickled in around 995, forced by kings like Olaf Tryggvason, who allegedly baptized the Orcadian earl Sigurd the Stout at swordpoint. Saint Magnus, co-earl from 1106-1117, became a martyr when his cousin Hakon had him axed during a power struggle—his cathedral in Kirkwall, started in 1137, stands as a red sandstone testament to Norse piety.

The islands' Norse identity deepened with the Norn language, a West Norse dialect that evolved into a unique tongue, full of words like "peerie" (small) that still pepper modern Orcadian and Shetlander speech. Genetics back this up: Studies show about 30% of Orkney's male lineages trace to western Norway, with bilateral Scandinavian ancestry around 44% in Shetland. Place names are overwhelmingly Norse—think "kirk" for church or "voe" for inlet. Law followed udal tenure, where land was owned outright without feudal overlords, passed down without written deeds. This allodial system clashed later with Scottish feudalism, leading to centuries of legal headaches.

By the 14th century, Norway's grip weakened. The Black Death ravaged Scandinavia in 1349, killing up to 60% of the population and shifting power to Denmark via the Kalmar Union in 1397, uniting Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under one crown. Orkney and Shetland became peripheral provinces, with earls like Henry Sinclair (d. 1400) juggling loyalties—he's the stuff of legends, allegedly sailing to North America in 1398, beating Columbus by a century (though evidence is shaky, involving dubious maps and Templar conspiracy theories). Enter the 15th century and our main players. King Christian I, born in 1426, inherited a triple crown in 1448 but faced endless rebellions and empty treasuries. Denmark's economy leaned east toward the Baltic trade, making the distant Northern Isles more burden than boon. In 1455, he married Dorothea of Brandenburg, but by 1460, he needed an alliance for his daughter Margaret. Scotland, under the young James III (born 1451, crowned at 9 after his father's explosive death—literally, from a cannon mishap), was eyeing expansion. Feuds over Hebrides taxes and Isle of Man claims simmered, but Charles VII of France suggested a marriage to cool things off.

Negotiations dragged from 1460, with Scotland demanding debt forgiveness and island concessions. By 1468, the deal was set: Margaret, aged 12, would wed James, 17, with a 60,000 Rhenish florins dowry—10,000 upfront, the rest in installments. But Christian was broke; Sweden rebelled, draining funds. So, on September 8, 1468, he pawned his personal Orkney lands for 50,000 florins, without his Norwegian council's (Riksråd) approval— a sneaky move, as udal law limited his ownership to a sliver of the islands. The contract, signed in Copenhagen, allowed redemption for 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver, and stipulated Norwegian laws and language must persist.

Shetland followed on May 28, 1469, pawned for a paltry 8,000 florins—insultingly low compared to Orkney's fertile farms, reflecting Shetland's rockier terrain. Again, redemption rights were baked in. Margaret sailed to Scotland, marrying James at Holyrood Abbey in July 1469. She proved a hit: beautiful, sensible, fashion-forward (blue velvet gowns, pearl nets), and politically astute. She bore three sons, including future James IV, and secured a massive jointure—one-third of royal revenues, plus palaces.

Enter the 15th century and our main players. King Christian I, born in 1426, inherited a triple crown in 1448 but faced endless rebellions and empty treasuries. Denmark's economy leaned east toward the Baltic trade, making the distant Northern Isles more burden than boon. In 1455, he married Dorothea of Brandenburg, but by 1460, he needed an alliance for his daughter Margaret. Scotland, under the young James III (born 1451, crowned at 9 after his father's explosive death—literally, from a cannon mishap), was eyeing expansion. Feuds over Hebrides taxes and Isle of Man claims simmered, but Charles VII of France suggested a marriage to cool things off.

Negotiations dragged from 1460, with Scotland demanding debt forgiveness and island concessions. By 1468, the deal was set: Margaret, aged 12, would wed James, 17, with a 60,000 Rhenish florins dowry—10,000 upfront, the rest in installments. But Christian was broke; Sweden rebelled, draining funds. So, on September 8, 1468, he pawned his personal Orkney lands for 50,000 florins, without his Norwegian council's (Riksråd) approval— a sneaky move, as udal law limited his ownership to a sliver of the islands. The contract, signed in Copenhagen, allowed redemption for 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver, and stipulated Norwegian laws and language must persist.

Shetland followed on May 28, 1469, pawned for a paltry 8,000 florins—insultingly low compared to Orkney's fertile farms, reflecting Shetland's rockier terrain. Again, redemption rights were baked in. Margaret sailed to Scotland, marrying James at Holyrood Abbey in July 1469. She proved a hit: beautiful, sensible, fashion-forward (blue velvet gowns, pearl nets), and politically astute. She bore three sons, including future James IV, and secured a massive jointure—one-third of royal revenues, plus palaces. But the dowry? Never paid. Christian imposed taxes to raise funds but failed. In 1470, William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness and last Norse Earl of Orkney, ceded his titles to James III in exchange for Ravenscraig Castle in Fife—a sweet deal for Scotland. This cleared the path for full annexation. On February 20, 1472, the Scottish Parliament passed an act declaring Orkney and Shetland "annexed to the crown" forever, citing the unpaid pledge. It was less a conquest than a foreclosure—Norway's bad credit score handing Scotland prime real estate.

The Norwegian and Danish councils fumed, calling it an "affront." They forced successors like King Hans to swear oaths at coronations to redeem the islands. Embassies in 1549, 1550, and beyond pleaded for return, but Scotland stonewalled. A 1473 letter from James III to Hans acknowledged the pledge but dodged repayment. Even the 1667 Treaty of Breda, post-English-Dutch wars, confirmed Scotland's hold. Christian wrote a poignant letter to the islanders: "Dear friends, you know that you rightly belong under the crown of Norway, even though you are pawned..." But belonging and possessing are different things.

Post-1472, the islands' Norse soul lingered but faded. Norn survived until the 18th century, suppressed by Scottish kirks and schools. Udal law clashed with feudalism; lairds like Robert Stewart (James V's bastard son, earl from 1581) imposed harsh rents, sparking revolts. His son Patrick "Black Pat" Stewart built Scalloway Castle with forced labor, only to be executed in 1615 for treason. Cromwell's troops in the 1650s used St. Magnus Cathedral as barracks, nearly wrecking it. The 1669 Act of Parliament made the isles Crown dependencies, exempt from some feudal rules, affirming udal rights in theory.

Economically, Hanseatic trade (German merchants) dominated pre-1707, exporting fish and wool. Post-Union, local lairds monopolized, causing depressions—Shetland's population boomed to 40,000 by 1861, then crashed from emigration and wars. Over 3,000 Shetlanders fought in Napoleonic Wars; in WWII, the "Shetland Bus" ran covert ops to Norway, with heroes like Leif Larsen making 52 trips in fishing boats.

Culturally, the shift was bittersweet. Scots dismissed Orcadians as "ferry-loupers" (island-hoppers), but Norse pride endures in festivals like Up Helly Aa, where squads in Viking gear torch a longship. Archaeology reveals blended heritage: Viking combs alongside Pictish stones. Lesser-known gems? Christian pawned only his lands, not the people's—under udal, islanders owned outright, making the deal legally dodgy. And that 1398 Sinclair voyage? A Zeno map claims he reached "Estotiland" (possibly Nova Scotia), fueling Templar myths.

Fast-forward through Jacobite risings (Orkney sided with Hanoverians), 19th-century kelp booms, and oil discoveries in the 1970s that brought prosperity. Today, Orkney and Shetland boast wind farms, ancient sites drawing tourists, and a distinct identity—closer to Bergen than Edinburgh in spirit. Debates over independence flare; some joke about rejoining Norway, but the 1472 act sealed their Scottish fate.

But the dowry? Never paid. Christian imposed taxes to raise funds but failed. In 1470, William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness and last Norse Earl of Orkney, ceded his titles to James III in exchange for Ravenscraig Castle in Fife—a sweet deal for Scotland. This cleared the path for full annexation. On February 20, 1472, the Scottish Parliament passed an act declaring Orkney and Shetland "annexed to the crown" forever, citing the unpaid pledge. It was less a conquest than a foreclosure—Norway's bad credit score handing Scotland prime real estate.

The Norwegian and Danish councils fumed, calling it an "affront." They forced successors like King Hans to swear oaths at coronations to redeem the islands. Embassies in 1549, 1550, and beyond pleaded for return, but Scotland stonewalled. A 1473 letter from James III to Hans acknowledged the pledge but dodged repayment. Even the 1667 Treaty of Breda, post-English-Dutch wars, confirmed Scotland's hold. Christian wrote a poignant letter to the islanders: "Dear friends, you know that you rightly belong under the crown of Norway, even though you are pawned..." But belonging and possessing are different things.

Post-1472, the islands' Norse soul lingered but faded. Norn survived until the 18th century, suppressed by Scottish kirks and schools. Udal law clashed with feudalism; lairds like Robert Stewart (James V's bastard son, earl from 1581) imposed harsh rents, sparking revolts. His son Patrick "Black Pat" Stewart built Scalloway Castle with forced labor, only to be executed in 1615 for treason. Cromwell's troops in the 1650s used St. Magnus Cathedral as barracks, nearly wrecking it. The 1669 Act of Parliament made the isles Crown dependencies, exempt from some feudal rules, affirming udal rights in theory.

Economically, Hanseatic trade (German merchants) dominated pre-1707, exporting fish and wool. Post-Union, local lairds monopolized, causing depressions—Shetland's population boomed to 40,000 by 1861, then crashed from emigration and wars. Over 3,000 Shetlanders fought in Napoleonic Wars; in WWII, the "Shetland Bus" ran covert ops to Norway, with heroes like Leif Larsen making 52 trips in fishing boats.

Culturally, the shift was bittersweet. Scots dismissed Orcadians as "ferry-loupers" (island-hoppers), but Norse pride endures in festivals like Up Helly Aa, where squads in Viking gear torch a longship. Archaeology reveals blended heritage: Viking combs alongside Pictish stones. Lesser-known gems? Christian pawned only his lands, not the people's—under udal, islanders owned outright, making the deal legally dodgy. And that 1398 Sinclair voyage? A Zeno map claims he reached "Estotiland" (possibly Nova Scotia), fueling Templar myths.

Fast-forward through Jacobite risings (Orkney sided with Hanoverians), 19th-century kelp booms, and oil discoveries in the 1970s that brought prosperity. Today, Orkney and Shetland boast wind farms, ancient sites drawing tourists, and a distinct identity—closer to Bergen than Edinburgh in spirit. Debates over independence flare; some joke about rejoining Norway, but the 1472 act sealed their Scottish fate. Whew—that's the epic saga, clocking in at over 2,700 words of historical deep-dive. But what's the point if it doesn't hit home? The dowry debacle teaches us about unintended consequences: A short-term fix became a 550-year shift. Christian's failure to pay up lost empires; James's opportunism gained them. In today's world of credit cards, loans, and life pivots, this translates to smart debt handling and adaptability.

Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life:

- **Avoid the Pawn Trap**: Like Christian pawning islands he couldn't redeem, don't overextend on loans or promises. Track expenses rigorously to prevent small debts snowballing into lost assets.

- **Seize Serendipity**: Scotland turned a default into dominion—spot opportunities in others' mishaps, like negotiating better deals when counterparts falter.

- **Preserve Your Roots Amid Change**: Islanders kept Norse customs despite Scottish rule; blend old habits with new realities for resilience.

- **Plan for Redemption**: Christian's tax flop shows poor follow-through kills recovery—build buffers for life's pledges.

- **Embrace Long-Term Vision**: The 1472 annexation outlasted kingdoms; think decades ahead in finances and relationships.

To apply this practically, follow this step-by-step plan:

Whew—that's the epic saga, clocking in at over 2,700 words of historical deep-dive. But what's the point if it doesn't hit home? The dowry debacle teaches us about unintended consequences: A short-term fix became a 550-year shift. Christian's failure to pay up lost empires; James's opportunism gained them. In today's world of credit cards, loans, and life pivots, this translates to smart debt handling and adaptability.

Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life:

- **Avoid the Pawn Trap**: Like Christian pawning islands he couldn't redeem, don't overextend on loans or promises. Track expenses rigorously to prevent small debts snowballing into lost assets.

- **Seize Serendipity**: Scotland turned a default into dominion—spot opportunities in others' mishaps, like negotiating better deals when counterparts falter.

- **Preserve Your Roots Amid Change**: Islanders kept Norse customs despite Scottish rule; blend old habits with new realities for resilience.

- **Plan for Redemption**: Christian's tax flop shows poor follow-through kills recovery—build buffers for life's pledges.

- **Embrace Long-Term Vision**: The 1472 annexation outlasted kingdoms; think decades ahead in finances and relationships.

To apply this practically, follow this step-by-step plan:

**Audit Your "Dowry"**: List all debts and commitments weekly—use an app like Mint to categorize and prioritize payoffs, aiming to clear high-interest ones first, just as Christian should have focused on that 60,000 florins.

**Build a Redemption Fund**: Set aside 10% of income into an emergency savings account, taxed like Christian's failed levy but actually enforced—automate transfers to grow it steadily.

**Negotiate Like James**: Review contracts (loans, leases) annually for leverage; if lenders slip, renegotiate terms or switch providers, turning potential defaults into gains.

**Cultural Adaptation Drill**: Monthly, reflect on a personal "annexation" (job change, move)—journal how to retain core values while integrating new elements, boosting adaptability.

**Long-Haul Review**: Annually, map 5-10 year goals against current actions; adjust like Scotland's parliament did, ensuring today's pawns don't become tomorrow's losses.

There you have it—a motivational nudge from 1472 to propel you forward. History isn't just dates; it's a blueprint for better living. Who knew a royal wedding flop could be so inspiring?

This tale isn't just about dusty old kings and forgotten treaties—it's a whirlwind of Viking conquests, political intrigue, cultural clashes, and economic face-plants that shaped the map of northern Europe. We'll dive deep into the historical nitty-gritty, uncovering how these islands went from Norse strongholds to Scottish outposts, with plenty of educational detours into archaeology, genetics, and even a dash of royal scandal. Along the way, I'll sprinkle in some humor because, let's face it, watching medieval monarchs fumble their finances is timeless comedy. And at the end? We'll pivot to how this ancient blunder can motivate you today—turning historical hindsight into personal foresight. Buckle up; this is going to be a long, enlightening ride through the misty isles. Let's start at the beginning, way back when these islands weren't even on most Europeans' maps. Orkney and Shetland, collectively known as the Northern Isles, sit like stubborn sentinels off Scotland's northern tip—Orkney closer to the mainland, a cluster of about 70 islands (20 inhabited), and Shetland farther north, with over 100 islands (15 inhabited). Their history kicks off around 8,800 years ago, when the last ice age glaciers retreated, leaving behind fertile (if chilly) land for hunter-gatherers. Archaeological digs reveal Mesolithic folks chasing seals and birds, but things really heated up in the Neolithic era, around 3500 BC. That's when farming arrived, and these early islanders built some of the most mind-blowing structures in prehistoric Europe. Take Skara Brae on Orkney's Mainland—it's like a Stone Age suburb preserved in sand after a storm buried it around 2500 BC. Excavated in the 1850s, this village of eight connected houses features stone beds, dressers for displaying pottery, and even indoor toilets flushed by streams. Imagine: These people had better plumbing than some medieval castles! Linked to grooved ware pottery, Skara Brae ties into the nearby Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, massive stone circles that Professor Alexander Thom theorized were ancient observatories for tracking lunar cycles. Not far away, Maeshowe is a chambered tomb with Viking graffiti scratched into the walls centuries later—rude runes like "Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes," proving even Norsemen couldn't resist tagging historic sites.

Shetland's prehistoric scene is similar but wilder, with sites like Jarlshof spanning 4,000 years of occupation—from Neolithic houses to Iron Age brochs (those iconic round towers) to Viking longhouses. The Broch of Mousa, a 13-meter-high stone tower on a tiny island, is the best-preserved in Scotland, complete with internal staircases and a view that screams "impenetrable fortress." These brochs, built around 100 BC to 100 AD, were likely status symbols for Iron Age chieftains, surrounded by ditches and ramparts. Artifacts include quern-stones for grinding grain, bone combs, and simple pottery, hinting at a society focused on survival in a harsh climate. By the Pictish era (around 300-900 AD), the islands were home to mysterious symbol stones and roundhouses. The Picts, those enigmatic tattooed warriors described by Romans as "painted people," left behind art like the ogham-inscribed stones on Orkney. Romans knew of the islands as "Orcades," possibly trading there or even briefly administering them as a province after Agricola's fleet circumnavigated Britain in 84 AD. But the real game-changer came with the Vikings in the 8th-9th centuries. Norsemen, fleeing overpopulation and seeking plunder, turned the Northern Isles into a launchpad for raids on Scotland and Ireland. Picture Harald Hårfagre (Fairhair), the first king to unify Norway around 875 AD. After a messy family feud, he sailed west to quash rebellious Vikings using Orkney as a base. Legend has it he annexed the islands after his son was killed in battle—compensation granted to Ragnvald, Earl of Møre, who then passed the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty. Sigurd expanded south, conquering parts of Scotland, but met a comical end: He beheaded a Scottish chieftain, tied the head to his saddle, and got fatally scratched by the dead man's tooth. Talk about a biting comeback! Under Norwegian rule, Orkney and Shetland flourished as earldoms. Key jarls included Turf-Einar (d. 910), who avenged his father's death by blood-eagling the culprit (a gruesome ritual of carving an eagle into the back), and Thorfinn the Mighty (d. 1065), who ruled from Dublin to Shetland like a mini-emperor. Christianity trickled in around 995, forced by kings like Olaf Tryggvason, who allegedly baptized the Orcadian earl Sigurd the Stout at swordpoint. Saint Magnus, co-earl from 1106-1117, became a martyr when his cousin Hakon had him axed during a power struggle—his cathedral in Kirkwall, started in 1137, stands as a red sandstone testament to Norse piety. The islands' Norse identity deepened with the Norn language, a West Norse dialect that evolved into a unique tongue, full of words like "peerie" (small) that still pepper modern Orcadian and Shetlander speech. Genetics back this up: Studies show about 30% of Orkney's male lineages trace to western Norway, with bilateral Scandinavian ancestry around 44% in Shetland. Place names are overwhelmingly Norse—think "kirk" for church or "voe" for inlet. Law followed udal tenure, where land was owned outright without feudal overlords, passed down without written deeds. This allodial system clashed later with Scottish feudalism, leading to centuries of legal headaches. By the 14th century, Norway's grip weakened. The Black Death ravaged Scandinavia in 1349, killing up to 60% of the population and shifting power to Denmark via the Kalmar Union in 1397, uniting Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under one crown. Orkney and Shetland became peripheral provinces, with earls like Henry Sinclair (d. 1400) juggling loyalties—he's the stuff of legends, allegedly sailing to North America in 1398, beating Columbus by a century (though evidence is shaky, involving dubious maps and Templar conspiracy theories).

Enter the 15th century and our main players. King Christian I, born in 1426, inherited a triple crown in 1448 but faced endless rebellions and empty treasuries. Denmark's economy leaned east toward the Baltic trade, making the distant Northern Isles more burden than boon. In 1455, he married Dorothea of Brandenburg, but by 1460, he needed an alliance for his daughter Margaret. Scotland, under the young James III (born 1451, crowned at 9 after his father's explosive death—literally, from a cannon mishap), was eyeing expansion. Feuds over Hebrides taxes and Isle of Man claims simmered, but Charles VII of France suggested a marriage to cool things off. Negotiations dragged from 1460, with Scotland demanding debt forgiveness and island concessions. By 1468, the deal was set: Margaret, aged 12, would wed James, 17, with a 60,000 Rhenish florins dowry—10,000 upfront, the rest in installments. But Christian was broke; Sweden rebelled, draining funds. So, on September 8, 1468, he pawned his personal Orkney lands for 50,000 florins, without his Norwegian council's (Riksråd) approval— a sneaky move, as udal law limited his ownership to a sliver of the islands. The contract, signed in Copenhagen, allowed redemption for 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver, and stipulated Norwegian laws and language must persist. Shetland followed on May 28, 1469, pawned for a paltry 8,000 florins—insultingly low compared to Orkney's fertile farms, reflecting Shetland's rockier terrain. Again, redemption rights were baked in. Margaret sailed to Scotland, marrying James at Holyrood Abbey in July 1469. She proved a hit: beautiful, sensible, fashion-forward (blue velvet gowns, pearl nets), and politically astute. She bore three sons, including future James IV, and secured a massive jointure—one-third of royal revenues, plus palaces.

But the dowry? Never paid. Christian imposed taxes to raise funds but failed. In 1470, William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness and last Norse Earl of Orkney, ceded his titles to James III in exchange for Ravenscraig Castle in Fife—a sweet deal for Scotland. This cleared the path for full annexation. On February 20, 1472, the Scottish Parliament passed an act declaring Orkney and Shetland "annexed to the crown" forever, citing the unpaid pledge. It was less a conquest than a foreclosure—Norway's bad credit score handing Scotland prime real estate. The Norwegian and Danish councils fumed, calling it an "affront." They forced successors like King Hans to swear oaths at coronations to redeem the islands. Embassies in 1549, 1550, and beyond pleaded for return, but Scotland stonewalled. A 1473 letter from James III to Hans acknowledged the pledge but dodged repayment. Even the 1667 Treaty of Breda, post-English-Dutch wars, confirmed Scotland's hold. Christian wrote a poignant letter to the islanders: "Dear friends, you know that you rightly belong under the crown of Norway, even though you are pawned..." But belonging and possessing are different things. Post-1472, the islands' Norse soul lingered but faded. Norn survived until the 18th century, suppressed by Scottish kirks and schools. Udal law clashed with feudalism; lairds like Robert Stewart (James V's bastard son, earl from 1581) imposed harsh rents, sparking revolts. His son Patrick "Black Pat" Stewart built Scalloway Castle with forced labor, only to be executed in 1615 for treason. Cromwell's troops in the 1650s used St. Magnus Cathedral as barracks, nearly wrecking it. The 1669 Act of Parliament made the isles Crown dependencies, exempt from some feudal rules, affirming udal rights in theory. Economically, Hanseatic trade (German merchants) dominated pre-1707, exporting fish and wool. Post-Union, local lairds monopolized, causing depressions—Shetland's population boomed to 40,000 by 1861, then crashed from emigration and wars. Over 3,000 Shetlanders fought in Napoleonic Wars; in WWII, the "Shetland Bus" ran covert ops to Norway, with heroes like Leif Larsen making 52 trips in fishing boats. Culturally, the shift was bittersweet. Scots dismissed Orcadians as "ferry-loupers" (island-hoppers), but Norse pride endures in festivals like Up Helly Aa, where squads in Viking gear torch a longship. Archaeology reveals blended heritage: Viking combs alongside Pictish stones. Lesser-known gems? Christian pawned only his lands, not the people's—under udal, islanders owned outright, making the deal legally dodgy. And that 1398 Sinclair voyage? A Zeno map claims he reached "Estotiland" (possibly Nova Scotia), fueling Templar myths. Fast-forward through Jacobite risings (Orkney sided with Hanoverians), 19th-century kelp booms, and oil discoveries in the 1970s that brought prosperity. Today, Orkney and Shetland boast wind farms, ancient sites drawing tourists, and a distinct identity—closer to Bergen than Edinburgh in spirit. Debates over independence flare; some joke about rejoining Norway, but the 1472 act sealed their Scottish fate.

Whew—that's the epic saga, clocking in at over 2,700 words of historical deep-dive. But what's the point if it doesn't hit home? The dowry debacle teaches us about unintended consequences: A short-term fix became a 550-year shift. Christian's failure to pay up lost empires; James's opportunism gained them. In today's world of credit cards, loans, and life pivots, this translates to smart debt handling and adaptability. Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life: - **Avoid the Pawn Trap**: Like Christian pawning islands he couldn't redeem, don't overextend on loans or promises. Track expenses rigorously to prevent small debts snowballing into lost assets. - **Seize Serendipity**: Scotland turned a default into dominion—spot opportunities in others' mishaps, like negotiating better deals when counterparts falter. - **Preserve Your Roots Amid Change**: Islanders kept Norse customs despite Scottish rule; blend old habits with new realities for resilience. - **Plan for Redemption**: Christian's tax flop shows poor follow-through kills recovery—build buffers for life's pledges. - **Embrace Long-Term Vision**: The 1472 annexation outlasted kingdoms; think decades ahead in finances and relationships. To apply this practically, follow this step-by-step plan: