On February 10, 1851, Governor Augustus French of Illinois picked up his pen and signed a charter that would forever change the young United States. With a few strokes of ink, the Illinois Central Railroad Company was born—the first railroad in America to receive a massive federal land grant to fund its construction. This was no modest local line. It was an audacious north-south spine running more than 700 miles through the heart of the prairie state, linking the muddy southern tip at Cairo (where the Ohio and Mississippi rivers meet) all the way to Chicago in the north, with a western branch stretching toward the lead mines of Galena. When completed in 1856, it was the longest railroad in the world, a gleaming iron artery that pumped commerce, people, and ambition through a still-wild continent. Before that February day, getting goods or people from central Illinois to market was an exercise in frustration and prayer. Rivers like the Mississippi and Illinois offered seasonal transport, but droughts, floods, snags, and ice could strand barges for months. Overland trails were little more than rutted mud paths where wagons sank axle-deep in spring thaws or choked on summer dust. Canals, like the recently finished Illinois and Michigan Canal, helped but were limited in reach and plagued by low water or maintenance woes. Farmers in the interior often burned excess corn for fuel because shipping it to distant buyers cost more than it was worth. Towns remained isolated, markets fragmented, and the vast prairie—rich black soil begging for plows—stayed largely empty.

The Illinois Central changed all that. It didn’t just lay tracks; it laid the foundation for modern America’s economic takeoff. In the decades that followed its chartering, the railroad turned Illinois into an agricultural powerhouse, supercharged Chicago’s rise as the nation’s transportation hub, helped win the Civil War, and set the template for how the federal government would partner with private enterprise to conquer distance itself. The story of February 10, 1851, is the story of visionaries, sweat-soaked laborers, shrewd politicians, and an iron will to connect a sprawling nation. And embedded in that story are timeless principles for anyone today who wants to move faster, reach farther, and build something durable in their own life.

### The Dream Takes Shape: From Canal Talk to Land-Grant Revolution

The idea of a north-south railroad through Illinois had been kicking around since the 1830s, when the state was still young and ambitious. Early boosters imagined a line that would link the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, creating a continuous water-and-rail corridor. But money was the eternal problem. Railroads were insanely expensive—rails, locomotives, bridges, labor, land. Private investors balked at the risk in a frontier state where population was sparse and returns uncertain.

Enter Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant” of Illinois politics. Douglas owned land near the proposed Chicago terminal and saw the railroad as both a public good and a personal windfall. He lobbied hard in Washington. In 1850, Congress passed the Illinois Central Land Grant Act, signed by President Millard Fillmore. It was groundbreaking: the federal government would grant the state roughly 2.6 million acres of public land—alternate sections in a checkerboard pattern along the proposed route—to be sold to finance construction. The state would then charter a private company to build and operate the line, with the land sales repaying the investment. This land-grant model became the blueprint for the transcontinental railroads that followed and for countless other infrastructure projects.

Before that February day, getting goods or people from central Illinois to market was an exercise in frustration and prayer. Rivers like the Mississippi and Illinois offered seasonal transport, but droughts, floods, snags, and ice could strand barges for months. Overland trails were little more than rutted mud paths where wagons sank axle-deep in spring thaws or choked on summer dust. Canals, like the recently finished Illinois and Michigan Canal, helped but were limited in reach and plagued by low water or maintenance woes. Farmers in the interior often burned excess corn for fuel because shipping it to distant buyers cost more than it was worth. Towns remained isolated, markets fragmented, and the vast prairie—rich black soil begging for plows—stayed largely empty.

The Illinois Central changed all that. It didn’t just lay tracks; it laid the foundation for modern America’s economic takeoff. In the decades that followed its chartering, the railroad turned Illinois into an agricultural powerhouse, supercharged Chicago’s rise as the nation’s transportation hub, helped win the Civil War, and set the template for how the federal government would partner with private enterprise to conquer distance itself. The story of February 10, 1851, is the story of visionaries, sweat-soaked laborers, shrewd politicians, and an iron will to connect a sprawling nation. And embedded in that story are timeless principles for anyone today who wants to move faster, reach farther, and build something durable in their own life.

### The Dream Takes Shape: From Canal Talk to Land-Grant Revolution

The idea of a north-south railroad through Illinois had been kicking around since the 1830s, when the state was still young and ambitious. Early boosters imagined a line that would link the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, creating a continuous water-and-rail corridor. But money was the eternal problem. Railroads were insanely expensive—rails, locomotives, bridges, labor, land. Private investors balked at the risk in a frontier state where population was sparse and returns uncertain.

Enter Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant” of Illinois politics. Douglas owned land near the proposed Chicago terminal and saw the railroad as both a public good and a personal windfall. He lobbied hard in Washington. In 1850, Congress passed the Illinois Central Land Grant Act, signed by President Millard Fillmore. It was groundbreaking: the federal government would grant the state roughly 2.6 million acres of public land—alternate sections in a checkerboard pattern along the proposed route—to be sold to finance construction. The state would then charter a private company to build and operate the line, with the land sales repaying the investment. This land-grant model became the blueprint for the transcontinental railroads that followed and for countless other infrastructure projects. On February 10, 1851, the Illinois General Assembly passed the incorporating act, and Governor French signed it into law. The charter named directors, set out the route (Cairo to LaSalle on the main line, with branches to Chicago and Galena), and transferred the federal land grant to the new company. To protect the public interest, the legislature appointed Samuel D. Lockwood—a respected former Supreme Court justice who had helped manage early federal land funds and the Illinois and Michigan Canal—to the board as a trustee.

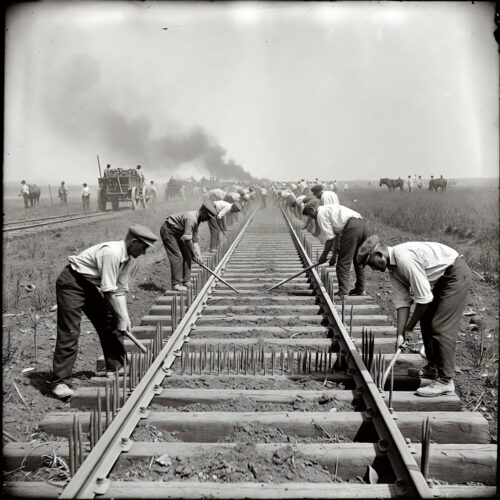

The company quickly organized. Directors met in New York City, elected Robert Schuyler as president, and began raising capital through stock subscriptions and European loans. Chief engineer Roswell B. Mason took charge of surveys starting in May 1851. Contractors broke ground later that year. The scale was staggering: more than 700 miles of track through forests, swamps, prairies, and river crossings. At peak construction, over 10,000 men labored simultaneously, with an estimated 100,000 workers involved over the five-year build. Immigrants—Irish, Germans, and others—swung picks and laid rails under brutal conditions. Malaria, accidents, and supply shortages were constant companions. In one stretch near LaSalle, 120 men reportedly died in just two days from disease or injury.

On February 10, 1851, the Illinois General Assembly passed the incorporating act, and Governor French signed it into law. The charter named directors, set out the route (Cairo to LaSalle on the main line, with branches to Chicago and Galena), and transferred the federal land grant to the new company. To protect the public interest, the legislature appointed Samuel D. Lockwood—a respected former Supreme Court justice who had helped manage early federal land funds and the Illinois and Michigan Canal—to the board as a trustee.

The company quickly organized. Directors met in New York City, elected Robert Schuyler as president, and began raising capital through stock subscriptions and European loans. Chief engineer Roswell B. Mason took charge of surveys starting in May 1851. Contractors broke ground later that year. The scale was staggering: more than 700 miles of track through forests, swamps, prairies, and river crossings. At peak construction, over 10,000 men labored simultaneously, with an estimated 100,000 workers involved over the five-year build. Immigrants—Irish, Germans, and others—swung picks and laid rails under brutal conditions. Malaria, accidents, and supply shortages were constant companions. In one stretch near LaSalle, 120 men reportedly died in just two days from disease or injury. Despite the hardships, progress was remarkable. The Chicago-to-Indiana border segment opened in 1852, connecting the city to eastern markets for the first time by rail. By May 1853, the first 60 miles of the main line from LaSalle to Bloomington were running. Sections opened as they were completed, generating early revenue that funded further work. The full charter lines—705 miles within Illinois—were finished by September 1856. The Illinois Central was not only the longest railroad on the planet at the time; it was a marvel of 19th-century engineering, complete with impressive bridges, depots, and repair shops.

### Iron, Sweat, and Strategy: Building the Main Line of Mid-America

Construction revealed the railroad’s genius and its growing pains. The land grant was a masterstroke: the company sold alternate sections to settlers and speculators, using the proceeds to pay for rails imported from Britain and locomotives built in eastern shops. Towns sprang up along the route almost overnight—places like Centralia (named for the railroad) and countless whistle-stops that became thriving communities. Grain elevators, lumber yards, and coal mines followed the tracks. Farmers who once burned surplus crops now loaded them onto boxcars bound for Chicago or New Orleans.

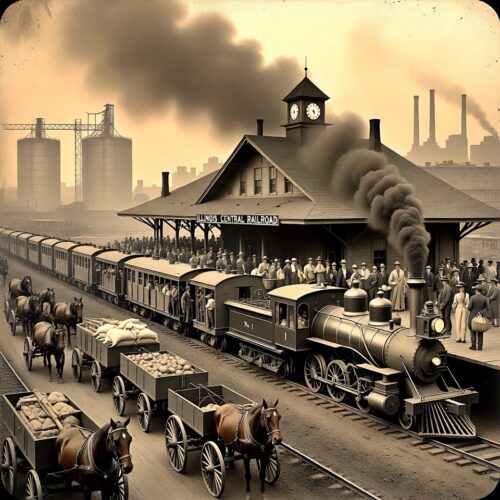

The economic ripple effects were enormous. Shipping costs plummeted. Corn that once cost a fortune to move by wagon or barge now traveled reliably and cheaply. Illinois’s prairie soil, some of the richest on Earth, fed a nation and beyond. Chicago exploded from a muddy outpost into the “hog butcher for the world,” its stockyards and grain markets fed by IC trains. The railroad also hauled lumber from northern forests southward and manufactured goods northward, knitting the Midwest into the national economy.

Socially, the IC reshaped demographics. It brought waves of settlers—European immigrants and American migrants—into previously isolated areas. Land sales programs actively recruited buyers in Europe, advertising fertile farms at low prices. The railroad became a corridor of opportunity, carrying families, tools, and dreams. Later, in the 20th century, it played a key role in the Great Migration, transporting African Americans from the South to northern industrial jobs.

Of course, not everything was triumphant. Construction displaced Native American communities whose lands were part of the granted sections. Labor conditions were often harsh, with long hours and dangerous work. Later strikes, including a violent 1911 shopmen’s walkout, highlighted tensions between workers and management. The company hired strikebreakers, including African American laborers, which deepened racial divides in some communities. Yet the overall trajectory was one of relentless expansion and integration.

### The Civil War Crucible: Rails That Carried Victory

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the Illinois Central proved its strategic worth. Chicago became the supply depot for Union armies in the Western Theater. General Ulysses S. Grant, operating from Cairo, used IC lines to move troops and matériel southward into Kentucky and Tennessee. The railroad transported hundreds of thousands of soldiers—estimates suggest 626,000 passenger-miles for military traffic alone—and vast quantities of freight. Its president during the war, William H. Osborn, coordinated closely with the War Department.

Despite the hardships, progress was remarkable. The Chicago-to-Indiana border segment opened in 1852, connecting the city to eastern markets for the first time by rail. By May 1853, the first 60 miles of the main line from LaSalle to Bloomington were running. Sections opened as they were completed, generating early revenue that funded further work. The full charter lines—705 miles within Illinois—were finished by September 1856. The Illinois Central was not only the longest railroad on the planet at the time; it was a marvel of 19th-century engineering, complete with impressive bridges, depots, and repair shops.

### Iron, Sweat, and Strategy: Building the Main Line of Mid-America

Construction revealed the railroad’s genius and its growing pains. The land grant was a masterstroke: the company sold alternate sections to settlers and speculators, using the proceeds to pay for rails imported from Britain and locomotives built in eastern shops. Towns sprang up along the route almost overnight—places like Centralia (named for the railroad) and countless whistle-stops that became thriving communities. Grain elevators, lumber yards, and coal mines followed the tracks. Farmers who once burned surplus crops now loaded them onto boxcars bound for Chicago or New Orleans.

The economic ripple effects were enormous. Shipping costs plummeted. Corn that once cost a fortune to move by wagon or barge now traveled reliably and cheaply. Illinois’s prairie soil, some of the richest on Earth, fed a nation and beyond. Chicago exploded from a muddy outpost into the “hog butcher for the world,” its stockyards and grain markets fed by IC trains. The railroad also hauled lumber from northern forests southward and manufactured goods northward, knitting the Midwest into the national economy.

Socially, the IC reshaped demographics. It brought waves of settlers—European immigrants and American migrants—into previously isolated areas. Land sales programs actively recruited buyers in Europe, advertising fertile farms at low prices. The railroad became a corridor of opportunity, carrying families, tools, and dreams. Later, in the 20th century, it played a key role in the Great Migration, transporting African Americans from the South to northern industrial jobs.

Of course, not everything was triumphant. Construction displaced Native American communities whose lands were part of the granted sections. Labor conditions were often harsh, with long hours and dangerous work. Later strikes, including a violent 1911 shopmen’s walkout, highlighted tensions between workers and management. The company hired strikebreakers, including African American laborers, which deepened racial divides in some communities. Yet the overall trajectory was one of relentless expansion and integration.

### The Civil War Crucible: Rails That Carried Victory

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the Illinois Central proved its strategic worth. Chicago became the supply depot for Union armies in the Western Theater. General Ulysses S. Grant, operating from Cairo, used IC lines to move troops and matériel southward into Kentucky and Tennessee. The railroad transported hundreds of thousands of soldiers—estimates suggest 626,000 passenger-miles for military traffic alone—and vast quantities of freight. Its president during the war, William H. Osborn, coordinated closely with the War Department. Subsidiary lines in the South suffered damage from Confederate raids, but post-war repairs under leaders like Absolom M. West restored service quickly. The IC’s reliability helped the Union maintain logistical superiority, contributing to victories at places like Shiloh and Vicksburg. In a very real sense, the railroad chartered on February 10, 1851, helped preserve the nation it had helped to knit together.

### Expansion, Innovation, and Enduring Legacy

After the war, the IC pushed further. It extended into Iowa, reached New Orleans and Mobile, and eventually operated lines to Sioux City, Omaha, and even connections to Florida. Passenger service became legendary: the all-Pullman Panama Limited from Chicago to New Orleans offered luxury travel, while the daytime City of New Orleans (immortalized in Arlo Guthrie’s song and Willie Nelson’s hit) carried everyday passengers through the heartland. Commuter lines in the Chicago area electrified early and served generations of suburban riders.

The company modernized with diesel locomotives, streamlined operations, and survived economic panics, world wars, and shifting transportation trends. Mergers and reorganizations followed—most notably the 1972 creation of the Illinois Central Gulf—but the core network endured. Today, much of the original IC route is operated by Canadian National Railway, a testament to its foundational strength. Museums preserve locomotives, depots, and artifacts, while historians credit the land-grant system pioneered here with accelerating America’s westward growth and industrialization.

The February 10, 1851, charter was more than paperwork. It was a bet on the future: that steel rails, federal vision, private enterprise, and sheer human effort could shrink a continent, unlock wealth, and bind a people. The outcome was a transformed Midwest, a stronger Union, and a model of infrastructure that still echoes in highways, airports, and digital networks today.

### Laying Your Own Tracks: Turning Historical Momentum into Personal Power

The Illinois Central’s story shows what happens when isolated points become connected by deliberate, durable infrastructure. Before the railroad, the prairie was full of potential but short on pathways. After, opportunity flowed in both directions. The same principle applies to individual lives. You don’t need congressional land grants to build systems that carry your goals forward—you just need vision, consistent effort, and smart connections.

Subsidiary lines in the South suffered damage from Confederate raids, but post-war repairs under leaders like Absolom M. West restored service quickly. The IC’s reliability helped the Union maintain logistical superiority, contributing to victories at places like Shiloh and Vicksburg. In a very real sense, the railroad chartered on February 10, 1851, helped preserve the nation it had helped to knit together.

### Expansion, Innovation, and Enduring Legacy

After the war, the IC pushed further. It extended into Iowa, reached New Orleans and Mobile, and eventually operated lines to Sioux City, Omaha, and even connections to Florida. Passenger service became legendary: the all-Pullman Panama Limited from Chicago to New Orleans offered luxury travel, while the daytime City of New Orleans (immortalized in Arlo Guthrie’s song and Willie Nelson’s hit) carried everyday passengers through the heartland. Commuter lines in the Chicago area electrified early and served generations of suburban riders.

The company modernized with diesel locomotives, streamlined operations, and survived economic panics, world wars, and shifting transportation trends. Mergers and reorganizations followed—most notably the 1972 creation of the Illinois Central Gulf—but the core network endured. Today, much of the original IC route is operated by Canadian National Railway, a testament to its foundational strength. Museums preserve locomotives, depots, and artifacts, while historians credit the land-grant system pioneered here with accelerating America’s westward growth and industrialization.

The February 10, 1851, charter was more than paperwork. It was a bet on the future: that steel rails, federal vision, private enterprise, and sheer human effort could shrink a continent, unlock wealth, and bind a people. The outcome was a transformed Midwest, a stronger Union, and a model of infrastructure that still echoes in highways, airports, and digital networks today.

### Laying Your Own Tracks: Turning Historical Momentum into Personal Power

The Illinois Central’s story shows what happens when isolated points become connected by deliberate, durable infrastructure. Before the railroad, the prairie was full of potential but short on pathways. After, opportunity flowed in both directions. The same principle applies to individual lives. You don’t need congressional land grants to build systems that carry your goals forward—you just need vision, consistent effort, and smart connections. Here are concrete ways the outcome of February 10, 1851, can benefit you today:

- **Survey Your Route First**: Just as engineers mapped the exact path from Cairo to Chicago before a single spike was driven, begin every major endeavor with clear planning. Specific action: Once per quarter, spend one uninterrupted hour listing your top three long-term destinations (career milestone, health target, relationship goal) and the precise “stations” (milestones) along the way. Write the first small step for each and schedule it on your calendar that same day.

- **Secure Your Land Grants**: The IC sold alternate sections of granted land to fund construction. Translate this by converting idle resources into fuel for progress. Specific action: Identify one underused asset—extra cash in a low-interest account, unused skills, or spare time—and redirect 10 percent of it monthly into a dedicated “construction fund” for education, equipment, or experiences that compound over time. Track the growth in a simple notebook.

- **Recruit a Construction Crew**: Building 700 miles required thousands of coordinated workers. Build your support network deliberately. Specific action: Each month, initiate contact with two people who are farther along your desired path—one for advice, one for potential collaboration. Prepare a brief value-offer (an article, introduction, or question) before reaching out, and follow up within a week to solidify the connection.

- **Lay Track Through the Swamps**: The IC crews didn’t detour around difficult terrain; they engineered solutions. Face obstacles head-on with systematic effort. Specific action: When encountering a persistent problem (procrastination on a project, financial leak, or skill gap), break it into daily 25-minute work sessions for two weeks straight. Log progress each evening and adjust tactics on day eight based on what’s working.

- **Build Branch Lines for Resilience**: The Chicago and Galena branches expanded the IC’s reach and redundancy. Diversify your capabilities and income streams. Specific action: Choose one complementary skill or side pursuit related to your main focus and invest 5 hours per week learning or practicing it for the next 90 days. Examples include adding data analysis to a creative role or learning basic marketing for a technical career. Test it with one small paid or public project by the end of the period.

- **Maintain the Line Relentlessly**: Even the strongest railroad needs constant upkeep to avoid derailments. Institute regular reviews. Specific action: On the first Saturday of every month, conduct a 45-minute “track inspection”: review your habits, finances, relationships, and health metrics. Fix one small issue immediately and schedule one bigger repair for the following week.

### Your 60-Day Track-Laying Plan: From Vision to Velocity

To turn inspiration into iron, follow this phased blueprint modeled on the IC’s own rapid yet methodical construction.

**Days 1–15: Survey and Charter**

Define your main line. Write a one-page vision document describing where you want to be in three years and why it matters. Identify your “Cairo to Chicago” route: the core project or goal. Secure initial resources—open a dedicated account or calendar block—and sign your personal “charter” by committing publicly to one trusted person.

**Days 16–30: Clear the Right-of-Way**

Remove obstacles. Tackle the three biggest current barriers (time wasters, outdated tools, limiting beliefs) with targeted actions. Sell or donate one unused item to free up space or cash. Establish one non-negotiable daily habit that supports your route, such as a 20-minute planning session or movement break.

**Days 31–45: Lay the First Miles**

Build momentum with visible progress. Complete one tangible milestone on your main goal—ship a product, finish a certification module, or have a key conversation. Recruit your first two “crew members” as described earlier. Open the first “station” by sharing an early win or lesson publicly (blog post, social update, or conversation) to generate accountability and feedback.

**Days 46–60: Connect the Branches and Inspect**

Add one branch line: start the complementary skill or stream outlined above. Run a full system test—simulate a “derailment” scenario (what if a key resource disappears?) and write your contingency. Celebrate the first 60 days with a deliberate reward tied to your vision, then schedule the next cycle with adjustments based on what accelerated or slowed progress.

Repeat and expand. The Illinois Central didn’t stop at 705 miles; it grew into a continental network. Your systems can do the same—starting with the decisive act of chartering your own future on any given day, including this one.

The iron rails laid after February 10, 1851, carried grain to markets, soldiers to battles, families to new homes, and ideas across distances once thought insurmountable. They turned potential into prosperity. Your life holds the same raw material: time, talent, and territory waiting to be connected. Don’t wait for perfect conditions or a congressional grant. Pick up your own tools, survey your route, and start laying track. The whistle is blowing— all aboard your personal Main Line of Mid-America. The journey begins now, and the destinations are yours to claim.

Here are concrete ways the outcome of February 10, 1851, can benefit you today:

- **Survey Your Route First**: Just as engineers mapped the exact path from Cairo to Chicago before a single spike was driven, begin every major endeavor with clear planning. Specific action: Once per quarter, spend one uninterrupted hour listing your top three long-term destinations (career milestone, health target, relationship goal) and the precise “stations” (milestones) along the way. Write the first small step for each and schedule it on your calendar that same day.

- **Secure Your Land Grants**: The IC sold alternate sections of granted land to fund construction. Translate this by converting idle resources into fuel for progress. Specific action: Identify one underused asset—extra cash in a low-interest account, unused skills, or spare time—and redirect 10 percent of it monthly into a dedicated “construction fund” for education, equipment, or experiences that compound over time. Track the growth in a simple notebook.

- **Recruit a Construction Crew**: Building 700 miles required thousands of coordinated workers. Build your support network deliberately. Specific action: Each month, initiate contact with two people who are farther along your desired path—one for advice, one for potential collaboration. Prepare a brief value-offer (an article, introduction, or question) before reaching out, and follow up within a week to solidify the connection.

- **Lay Track Through the Swamps**: The IC crews didn’t detour around difficult terrain; they engineered solutions. Face obstacles head-on with systematic effort. Specific action: When encountering a persistent problem (procrastination on a project, financial leak, or skill gap), break it into daily 25-minute work sessions for two weeks straight. Log progress each evening and adjust tactics on day eight based on what’s working.

- **Build Branch Lines for Resilience**: The Chicago and Galena branches expanded the IC’s reach and redundancy. Diversify your capabilities and income streams. Specific action: Choose one complementary skill or side pursuit related to your main focus and invest 5 hours per week learning or practicing it for the next 90 days. Examples include adding data analysis to a creative role or learning basic marketing for a technical career. Test it with one small paid or public project by the end of the period.

- **Maintain the Line Relentlessly**: Even the strongest railroad needs constant upkeep to avoid derailments. Institute regular reviews. Specific action: On the first Saturday of every month, conduct a 45-minute “track inspection”: review your habits, finances, relationships, and health metrics. Fix one small issue immediately and schedule one bigger repair for the following week.

### Your 60-Day Track-Laying Plan: From Vision to Velocity

To turn inspiration into iron, follow this phased blueprint modeled on the IC’s own rapid yet methodical construction.

**Days 1–15: Survey and Charter**

Define your main line. Write a one-page vision document describing where you want to be in three years and why it matters. Identify your “Cairo to Chicago” route: the core project or goal. Secure initial resources—open a dedicated account or calendar block—and sign your personal “charter” by committing publicly to one trusted person.

**Days 16–30: Clear the Right-of-Way**

Remove obstacles. Tackle the three biggest current barriers (time wasters, outdated tools, limiting beliefs) with targeted actions. Sell or donate one unused item to free up space or cash. Establish one non-negotiable daily habit that supports your route, such as a 20-minute planning session or movement break.

**Days 31–45: Lay the First Miles**

Build momentum with visible progress. Complete one tangible milestone on your main goal—ship a product, finish a certification module, or have a key conversation. Recruit your first two “crew members” as described earlier. Open the first “station” by sharing an early win or lesson publicly (blog post, social update, or conversation) to generate accountability and feedback.

**Days 46–60: Connect the Branches and Inspect**

Add one branch line: start the complementary skill or stream outlined above. Run a full system test—simulate a “derailment” scenario (what if a key resource disappears?) and write your contingency. Celebrate the first 60 days with a deliberate reward tied to your vision, then schedule the next cycle with adjustments based on what accelerated or slowed progress.

Repeat and expand. The Illinois Central didn’t stop at 705 miles; it grew into a continental network. Your systems can do the same—starting with the decisive act of chartering your own future on any given day, including this one.

The iron rails laid after February 10, 1851, carried grain to markets, soldiers to battles, families to new homes, and ideas across distances once thought insurmountable. They turned potential into prosperity. Your life holds the same raw material: time, talent, and territory waiting to be connected. Don’t wait for perfect conditions or a congressional grant. Pick up your own tools, survey your route, and start laying track. The whistle is blowing— all aboard your personal Main Line of Mid-America. The journey begins now, and the destinations are yours to claim.

Before that February day, getting goods or people from central Illinois to market was an exercise in frustration and prayer. Rivers like the Mississippi and Illinois offered seasonal transport, but droughts, floods, snags, and ice could strand barges for months. Overland trails were little more than rutted mud paths where wagons sank axle-deep in spring thaws or choked on summer dust. Canals, like the recently finished Illinois and Michigan Canal, helped but were limited in reach and plagued by low water or maintenance woes. Farmers in the interior often burned excess corn for fuel because shipping it to distant buyers cost more than it was worth. Towns remained isolated, markets fragmented, and the vast prairie—rich black soil begging for plows—stayed largely empty. The Illinois Central changed all that. It didn’t just lay tracks; it laid the foundation for modern America’s economic takeoff. In the decades that followed its chartering, the railroad turned Illinois into an agricultural powerhouse, supercharged Chicago’s rise as the nation’s transportation hub, helped win the Civil War, and set the template for how the federal government would partner with private enterprise to conquer distance itself. The story of February 10, 1851, is the story of visionaries, sweat-soaked laborers, shrewd politicians, and an iron will to connect a sprawling nation. And embedded in that story are timeless principles for anyone today who wants to move faster, reach farther, and build something durable in their own life. ### The Dream Takes Shape: From Canal Talk to Land-Grant Revolution The idea of a north-south railroad through Illinois had been kicking around since the 1830s, when the state was still young and ambitious. Early boosters imagined a line that would link the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, creating a continuous water-and-rail corridor. But money was the eternal problem. Railroads were insanely expensive—rails, locomotives, bridges, labor, land. Private investors balked at the risk in a frontier state where population was sparse and returns uncertain. Enter Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant” of Illinois politics. Douglas owned land near the proposed Chicago terminal and saw the railroad as both a public good and a personal windfall. He lobbied hard in Washington. In 1850, Congress passed the Illinois Central Land Grant Act, signed by President Millard Fillmore. It was groundbreaking: the federal government would grant the state roughly 2.6 million acres of public land—alternate sections in a checkerboard pattern along the proposed route—to be sold to finance construction. The state would then charter a private company to build and operate the line, with the land sales repaying the investment. This land-grant model became the blueprint for the transcontinental railroads that followed and for countless other infrastructure projects.

On February 10, 1851, the Illinois General Assembly passed the incorporating act, and Governor French signed it into law. The charter named directors, set out the route (Cairo to LaSalle on the main line, with branches to Chicago and Galena), and transferred the federal land grant to the new company. To protect the public interest, the legislature appointed Samuel D. Lockwood—a respected former Supreme Court justice who had helped manage early federal land funds and the Illinois and Michigan Canal—to the board as a trustee. The company quickly organized. Directors met in New York City, elected Robert Schuyler as president, and began raising capital through stock subscriptions and European loans. Chief engineer Roswell B. Mason took charge of surveys starting in May 1851. Contractors broke ground later that year. The scale was staggering: more than 700 miles of track through forests, swamps, prairies, and river crossings. At peak construction, over 10,000 men labored simultaneously, with an estimated 100,000 workers involved over the five-year build. Immigrants—Irish, Germans, and others—swung picks and laid rails under brutal conditions. Malaria, accidents, and supply shortages were constant companions. In one stretch near LaSalle, 120 men reportedly died in just two days from disease or injury.

Despite the hardships, progress was remarkable. The Chicago-to-Indiana border segment opened in 1852, connecting the city to eastern markets for the first time by rail. By May 1853, the first 60 miles of the main line from LaSalle to Bloomington were running. Sections opened as they were completed, generating early revenue that funded further work. The full charter lines—705 miles within Illinois—were finished by September 1856. The Illinois Central was not only the longest railroad on the planet at the time; it was a marvel of 19th-century engineering, complete with impressive bridges, depots, and repair shops. ### Iron, Sweat, and Strategy: Building the Main Line of Mid-America Construction revealed the railroad’s genius and its growing pains. The land grant was a masterstroke: the company sold alternate sections to settlers and speculators, using the proceeds to pay for rails imported from Britain and locomotives built in eastern shops. Towns sprang up along the route almost overnight—places like Centralia (named for the railroad) and countless whistle-stops that became thriving communities. Grain elevators, lumber yards, and coal mines followed the tracks. Farmers who once burned surplus crops now loaded them onto boxcars bound for Chicago or New Orleans. The economic ripple effects were enormous. Shipping costs plummeted. Corn that once cost a fortune to move by wagon or barge now traveled reliably and cheaply. Illinois’s prairie soil, some of the richest on Earth, fed a nation and beyond. Chicago exploded from a muddy outpost into the “hog butcher for the world,” its stockyards and grain markets fed by IC trains. The railroad also hauled lumber from northern forests southward and manufactured goods northward, knitting the Midwest into the national economy. Socially, the IC reshaped demographics. It brought waves of settlers—European immigrants and American migrants—into previously isolated areas. Land sales programs actively recruited buyers in Europe, advertising fertile farms at low prices. The railroad became a corridor of opportunity, carrying families, tools, and dreams. Later, in the 20th century, it played a key role in the Great Migration, transporting African Americans from the South to northern industrial jobs. Of course, not everything was triumphant. Construction displaced Native American communities whose lands were part of the granted sections. Labor conditions were often harsh, with long hours and dangerous work. Later strikes, including a violent 1911 shopmen’s walkout, highlighted tensions between workers and management. The company hired strikebreakers, including African American laborers, which deepened racial divides in some communities. Yet the overall trajectory was one of relentless expansion and integration. ### The Civil War Crucible: Rails That Carried Victory When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the Illinois Central proved its strategic worth. Chicago became the supply depot for Union armies in the Western Theater. General Ulysses S. Grant, operating from Cairo, used IC lines to move troops and matériel southward into Kentucky and Tennessee. The railroad transported hundreds of thousands of soldiers—estimates suggest 626,000 passenger-miles for military traffic alone—and vast quantities of freight. Its president during the war, William H. Osborn, coordinated closely with the War Department.

Subsidiary lines in the South suffered damage from Confederate raids, but post-war repairs under leaders like Absolom M. West restored service quickly. The IC’s reliability helped the Union maintain logistical superiority, contributing to victories at places like Shiloh and Vicksburg. In a very real sense, the railroad chartered on February 10, 1851, helped preserve the nation it had helped to knit together. ### Expansion, Innovation, and Enduring Legacy After the war, the IC pushed further. It extended into Iowa, reached New Orleans and Mobile, and eventually operated lines to Sioux City, Omaha, and even connections to Florida. Passenger service became legendary: the all-Pullman Panama Limited from Chicago to New Orleans offered luxury travel, while the daytime City of New Orleans (immortalized in Arlo Guthrie’s song and Willie Nelson’s hit) carried everyday passengers through the heartland. Commuter lines in the Chicago area electrified early and served generations of suburban riders. The company modernized with diesel locomotives, streamlined operations, and survived economic panics, world wars, and shifting transportation trends. Mergers and reorganizations followed—most notably the 1972 creation of the Illinois Central Gulf—but the core network endured. Today, much of the original IC route is operated by Canadian National Railway, a testament to its foundational strength. Museums preserve locomotives, depots, and artifacts, while historians credit the land-grant system pioneered here with accelerating America’s westward growth and industrialization. The February 10, 1851, charter was more than paperwork. It was a bet on the future: that steel rails, federal vision, private enterprise, and sheer human effort could shrink a continent, unlock wealth, and bind a people. The outcome was a transformed Midwest, a stronger Union, and a model of infrastructure that still echoes in highways, airports, and digital networks today. ### Laying Your Own Tracks: Turning Historical Momentum into Personal Power The Illinois Central’s story shows what happens when isolated points become connected by deliberate, durable infrastructure. Before the railroad, the prairie was full of potential but short on pathways. After, opportunity flowed in both directions. The same principle applies to individual lives. You don’t need congressional land grants to build systems that carry your goals forward—you just need vision, consistent effort, and smart connections.

Here are concrete ways the outcome of February 10, 1851, can benefit you today: - **Survey Your Route First**: Just as engineers mapped the exact path from Cairo to Chicago before a single spike was driven, begin every major endeavor with clear planning. Specific action: Once per quarter, spend one uninterrupted hour listing your top three long-term destinations (career milestone, health target, relationship goal) and the precise “stations” (milestones) along the way. Write the first small step for each and schedule it on your calendar that same day. - **Secure Your Land Grants**: The IC sold alternate sections of granted land to fund construction. Translate this by converting idle resources into fuel for progress. Specific action: Identify one underused asset—extra cash in a low-interest account, unused skills, or spare time—and redirect 10 percent of it monthly into a dedicated “construction fund” for education, equipment, or experiences that compound over time. Track the growth in a simple notebook. - **Recruit a Construction Crew**: Building 700 miles required thousands of coordinated workers. Build your support network deliberately. Specific action: Each month, initiate contact with two people who are farther along your desired path—one for advice, one for potential collaboration. Prepare a brief value-offer (an article, introduction, or question) before reaching out, and follow up within a week to solidify the connection. - **Lay Track Through the Swamps**: The IC crews didn’t detour around difficult terrain; they engineered solutions. Face obstacles head-on with systematic effort. Specific action: When encountering a persistent problem (procrastination on a project, financial leak, or skill gap), break it into daily 25-minute work sessions for two weeks straight. Log progress each evening and adjust tactics on day eight based on what’s working. - **Build Branch Lines for Resilience**: The Chicago and Galena branches expanded the IC’s reach and redundancy. Diversify your capabilities and income streams. Specific action: Choose one complementary skill or side pursuit related to your main focus and invest 5 hours per week learning or practicing it for the next 90 days. Examples include adding data analysis to a creative role or learning basic marketing for a technical career. Test it with one small paid or public project by the end of the period. - **Maintain the Line Relentlessly**: Even the strongest railroad needs constant upkeep to avoid derailments. Institute regular reviews. Specific action: On the first Saturday of every month, conduct a 45-minute “track inspection”: review your habits, finances, relationships, and health metrics. Fix one small issue immediately and schedule one bigger repair for the following week. ### Your 60-Day Track-Laying Plan: From Vision to Velocity To turn inspiration into iron, follow this phased blueprint modeled on the IC’s own rapid yet methodical construction. **Days 1–15: Survey and Charter** Define your main line. Write a one-page vision document describing where you want to be in three years and why it matters. Identify your “Cairo to Chicago” route: the core project or goal. Secure initial resources—open a dedicated account or calendar block—and sign your personal “charter” by committing publicly to one trusted person. **Days 16–30: Clear the Right-of-Way** Remove obstacles. Tackle the three biggest current barriers (time wasters, outdated tools, limiting beliefs) with targeted actions. Sell or donate one unused item to free up space or cash. Establish one non-negotiable daily habit that supports your route, such as a 20-minute planning session or movement break. **Days 31–45: Lay the First Miles** Build momentum with visible progress. Complete one tangible milestone on your main goal—ship a product, finish a certification module, or have a key conversation. Recruit your first two “crew members” as described earlier. Open the first “station” by sharing an early win or lesson publicly (blog post, social update, or conversation) to generate accountability and feedback. **Days 46–60: Connect the Branches and Inspect** Add one branch line: start the complementary skill or stream outlined above. Run a full system test—simulate a “derailment” scenario (what if a key resource disappears?) and write your contingency. Celebrate the first 60 days with a deliberate reward tied to your vision, then schedule the next cycle with adjustments based on what accelerated or slowed progress. Repeat and expand. The Illinois Central didn’t stop at 705 miles; it grew into a continental network. Your systems can do the same—starting with the decisive act of chartering your own future on any given day, including this one. The iron rails laid after February 10, 1851, carried grain to markets, soldiers to battles, families to new homes, and ideas across distances once thought insurmountable. They turned potential into prosperity. Your life holds the same raw material: time, talent, and territory waiting to be connected. Don’t wait for perfect conditions or a congressional grant. Pick up your own tools, survey your route, and start laying track. The whistle is blowing— all aboard your personal Main Line of Mid-America. The journey begins now, and the destinations are yours to claim.