Ah, history—the ultimate reality show where the stakes are empires, the drama is endless, and the plot twists could make a soap opera blush. Picture this: it's the late 11th century, a time when knights in shining armor weren't just fairy tale fodder but real-life adrenaline junkies charging into the unknown on a divine quest. On February 9, 1098, amid the rugged hills of what is now southern Turkey, a ragtag band of European Crusaders pulled off one of the most audacious upsets in military annals. The Battle of the Lake of Antioch wasn't just a skirmish; it was a desperate gamble that saved the First Crusade from collapse and echoed through centuries of warfare. We'll dive deep into the mud, blood, and sheer chutzpah of that fateful day—because who doesn't love a story where 700 underfed knights trounce 12,000 foes? And stick around, because we'll twist this ancient tale into a motivational blueprint for your modern life. But first, let's rewind the clock and unpack the chaos that led to this lakeside showdown.

The First Crusade didn't start as a well-oiled machine; it was more like a medieval road trip gone horribly wrong. Launched in 1096 by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont, the call to arms was a fiery sermon urging Western Christians to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim control. Urban painted a picture of holy lands desecrated, pilgrims persecuted, and a divine mandate to fight back. Thousands answered—knights, peasants, nobles, even kids in the ill-fated People's Crusade that got wiped out before reaching Constantinople. The main force, however, comprised seasoned warriors from France, Italy, and Germany, led by figures like Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond IV of Toulouse, and the ambitious Bohemond of Taranto.

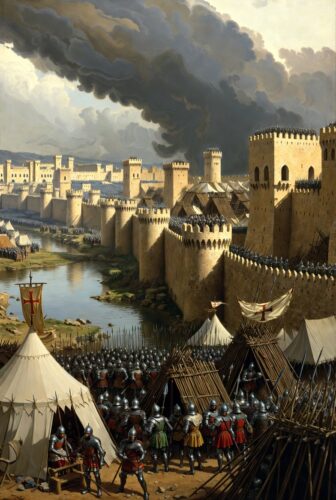

These weren't your average tourists. The Crusaders trudged over 2,000 miles across Europe and Asia Minor, battling hunger, disease, and hostile locals. By the summer of 1097, they had scored a big win at the Battle of Dorylaeum against the Seljuq Turks, proving their heavy cavalry could smash lighter Muslim forces in open fields. But Antioch loomed as the real test. This ancient city, founded by one of Alexander the Great's generals in 300 BC, was a jewel of the Byzantine Empire until the Seljuqs seized it in 1085. Perched on the Orontes River with massive walls—some 12 kilometers long, studded with 400 towers—it was a fortress that laughed at invaders. Controlling Antioch meant securing supply lines from the Mediterranean to the Levant, a gateway to Jerusalem itself. The siege kicked off on October 21, 1097. The Crusaders, numbering around 40,000 at the start (including non-combatants), encircled the city but couldn't fully blockade it due to its size and terrain. Yaghi-Siyan, the wily Turkish governor, had stocked up on supplies and commanded a garrison of several thousand. He played a smart game: harassing the besiegers with sorties, poisoning wells, and sending pleas for help to neighboring emirs. The Crusaders, meanwhile, built makeshift forts like Malregard and Tancred's Tower to tighten the noose, but winter hit hard. Rain turned camps into swamps, food ran scarce, and dysentery ravaged the ranks. Horses died by the hundreds—vital for the knights' shock tactics—leaving many to ride donkeys or oxen. Morale plummeted; deserters fled, including high-profile ones like Peter the Hermit, who was dragged back in chains.

By December, things got dire. A foraging party under Bohemond and Robert II of Flanders clashed with a relief force from Damascus led by Duqaq at the Battle of Harenc on December 31. The Crusaders won, but barely, capturing precious supplies. Yaghi-Siyan, undeterred, dispatched his son Shams ad-Daulah to rally more aid. Shams first hit up Duqaq, who was licking his wounds and declined. Undaunted, he headed to Aleppo, where Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan ruled. Radwan, a Seljuq sultan in his early 20s, had just patched up a feud with his brother Duqaq—sibling rivalries were as common in medieval Islam as they were explosive. Seeing a chance to boost his prestige, Radwan assembled a coalition: his own Aleppan troops, Artuqid allies under Soqman ibn Ortoq, and forces from Hamah. By early February 1098, this army—estimated at 12,000 strong, including archers, light cavalry, and infantry—camped at Harim, just 35 kilometers east of Antioch.

The siege kicked off on October 21, 1097. The Crusaders, numbering around 40,000 at the start (including non-combatants), encircled the city but couldn't fully blockade it due to its size and terrain. Yaghi-Siyan, the wily Turkish governor, had stocked up on supplies and commanded a garrison of several thousand. He played a smart game: harassing the besiegers with sorties, poisoning wells, and sending pleas for help to neighboring emirs. The Crusaders, meanwhile, built makeshift forts like Malregard and Tancred's Tower to tighten the noose, but winter hit hard. Rain turned camps into swamps, food ran scarce, and dysentery ravaged the ranks. Horses died by the hundreds—vital for the knights' shock tactics—leaving many to ride donkeys or oxen. Morale plummeted; deserters fled, including high-profile ones like Peter the Hermit, who was dragged back in chains.

By December, things got dire. A foraging party under Bohemond and Robert II of Flanders clashed with a relief force from Damascus led by Duqaq at the Battle of Harenc on December 31. The Crusaders won, but barely, capturing precious supplies. Yaghi-Siyan, undeterred, dispatched his son Shams ad-Daulah to rally more aid. Shams first hit up Duqaq, who was licking his wounds and declined. Undaunted, he headed to Aleppo, where Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan ruled. Radwan, a Seljuq sultan in his early 20s, had just patched up a feud with his brother Duqaq—sibling rivalries were as common in medieval Islam as they were explosive. Seeing a chance to boost his prestige, Radwan assembled a coalition: his own Aleppan troops, Artuqid allies under Soqman ibn Ortoq, and forces from Hamah. By early February 1098, this army—estimated at 12,000 strong, including archers, light cavalry, and infantry—camped at Harim, just 35 kilometers east of Antioch. Word reached the Crusader camp via scouts and spies. Panic ensued. The leaders—Bohemond, Raymond, Godfrey, Robert of Flanders, and others—debated furiously. A full-scale assault from Radwan could pin them against Antioch's walls, with Yaghi-Siyan's garrison sallying out for a pincer move. Starvation had whittled their effective knights to about 700, a fraction of their original cavalry. In a bold move, they elected Bohemond as supreme commander for this crisis—the first time the Crusade had a unified leader. Bohemond, a towering Norman with a reputation for cunning (he'd fought Byzantines and Turks before), rejected a static defense at the Iron Bridge over the Orontes. That would invite attrition, playing to Radwan's numbers. Instead, he gambled on offense: a night march to ambush the relief force in a narrow defile between the river and the Lake of Antioch (modern Lake Amik, a marshy basin prone to flooding).

Under moonless skies on February 8, Bohemond's knights slipped across the Iron Bridge undetected. Muslim scouts watched by day but slacked off at night—classic overconfidence. The Crusaders rode east along the Aleppo road, hugging the Orontes on their left. Dawn broke on February 9 as they reached a hilly spot ideal for ambush: the terrain funneled enemies into a bottleneck, negating superior numbers. Bohemond divided his force into seven squadrons—five forward under leaders like Robert of Flanders, Tancred (Bohemond's nephew), and Adhemar of Le Puy (the papal legate, more spiritual than martial), with Bohemond holding the sixth and seventh in reserve. It was a classic feigned retreat setup, straight out of Norman playbook.

Radwan's army approached leisurely, unaware of the trap. He led with two vanguard squadrons screening the main body—archers on horseback, light lancers, and infantry. As they neared the hill, Bohemond sprang the ambush. The five forward squadrons charged downhill, lances couched, slamming into the Turkish flank. The impact was devastating: the vanguard crumpled, retreating into the deploying main force and sowing confusion. Arrows flew thick as the Turks regrouped, their horse archers peppering the knights. The Crusaders, armored in chainmail hauberks and conical helmets, absorbed the barrage but began to falter under sheer volume. Knights dismounted to fight on foot when horses failed, turning the melee into a brutal slog.

Here's where Bohemond's genius shone. Sensing the tipping point, he committed his reserves—fresh knights thundering in for the knockout blow. The charge shattered the Turkish center; panic spread like wildfire. Radwan's coalition fractured—Artuqids fled first, then others. The rout was total: Crusaders pursued for miles, hacking down fugitives and seizing baggage trains loaded with food, weapons, and horses. Back at Antioch, Yaghi-Siyan timed a sortie to hit the Crusader camp, but Raymond of Toulouse repelled it with infantry and crossbowmen. By midday, the battle was over. Crusader losses were minimal—perhaps a few dozen knights—while Radwan's army lost thousands, including key officers. Heads of the slain were paraded on pikes back to camp, a gruesome morale booster.

Word reached the Crusader camp via scouts and spies. Panic ensued. The leaders—Bohemond, Raymond, Godfrey, Robert of Flanders, and others—debated furiously. A full-scale assault from Radwan could pin them against Antioch's walls, with Yaghi-Siyan's garrison sallying out for a pincer move. Starvation had whittled their effective knights to about 700, a fraction of their original cavalry. In a bold move, they elected Bohemond as supreme commander for this crisis—the first time the Crusade had a unified leader. Bohemond, a towering Norman with a reputation for cunning (he'd fought Byzantines and Turks before), rejected a static defense at the Iron Bridge over the Orontes. That would invite attrition, playing to Radwan's numbers. Instead, he gambled on offense: a night march to ambush the relief force in a narrow defile between the river and the Lake of Antioch (modern Lake Amik, a marshy basin prone to flooding).

Under moonless skies on February 8, Bohemond's knights slipped across the Iron Bridge undetected. Muslim scouts watched by day but slacked off at night—classic overconfidence. The Crusaders rode east along the Aleppo road, hugging the Orontes on their left. Dawn broke on February 9 as they reached a hilly spot ideal for ambush: the terrain funneled enemies into a bottleneck, negating superior numbers. Bohemond divided his force into seven squadrons—five forward under leaders like Robert of Flanders, Tancred (Bohemond's nephew), and Adhemar of Le Puy (the papal legate, more spiritual than martial), with Bohemond holding the sixth and seventh in reserve. It was a classic feigned retreat setup, straight out of Norman playbook.

Radwan's army approached leisurely, unaware of the trap. He led with two vanguard squadrons screening the main body—archers on horseback, light lancers, and infantry. As they neared the hill, Bohemond sprang the ambush. The five forward squadrons charged downhill, lances couched, slamming into the Turkish flank. The impact was devastating: the vanguard crumpled, retreating into the deploying main force and sowing confusion. Arrows flew thick as the Turks regrouped, their horse archers peppering the knights. The Crusaders, armored in chainmail hauberks and conical helmets, absorbed the barrage but began to falter under sheer volume. Knights dismounted to fight on foot when horses failed, turning the melee into a brutal slog.

Here's where Bohemond's genius shone. Sensing the tipping point, he committed his reserves—fresh knights thundering in for the knockout blow. The charge shattered the Turkish center; panic spread like wildfire. Radwan's coalition fractured—Artuqids fled first, then others. The rout was total: Crusaders pursued for miles, hacking down fugitives and seizing baggage trains loaded with food, weapons, and horses. Back at Antioch, Yaghi-Siyan timed a sortie to hit the Crusader camp, but Raymond of Toulouse repelled it with infantry and crossbowmen. By midday, the battle was over. Crusader losses were minimal—perhaps a few dozen knights—while Radwan's army lost thousands, including key officers. Heads of the slain were paraded on pikes back to camp, a gruesome morale booster. The immediate aftermath was electric. The captured supplies—grain, livestock, tents—alleviated the siege's famine. Morale skyrocketed; deserters reconsidered. Bohemond's stock rose—he claimed Antioch as his prize, setting up future squabbles with Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who wanted the city back. But the siege dragged on. In March, an English fleet under Edgar Atheling docked at St. Symeon pier, bringing reinforcements and siege engines. Yaghi-Siyan grew desperate, executing Christian inhabitants and fortifying the citadel.

By May, betrayal brewed. Bohemond bribed an Armenian guard named Firouz, who controlled the Tower of the Two Sisters. On June 2, Firouz lowered ropes; Crusaders scaled the walls, opening gates for a massacre. Thousands of Turks died in the frenzy—Yaghi-Siyan fled but was beheaded by peasants. His son held the citadel briefly. But joy was short-lived: on June 5, a massive army under Kerbogha of Mosul arrived, besieging the besiegers. Starvation returned; visions of the Holy Lance (unearthed by Peter Bartholomew) rallied spirits. On June 28, the Crusaders sallied out in the Battle of Antioch proper, routing Kerbogha with reported angelic aid.

The immediate aftermath was electric. The captured supplies—grain, livestock, tents—alleviated the siege's famine. Morale skyrocketed; deserters reconsidered. Bohemond's stock rose—he claimed Antioch as his prize, setting up future squabbles with Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who wanted the city back. But the siege dragged on. In March, an English fleet under Edgar Atheling docked at St. Symeon pier, bringing reinforcements and siege engines. Yaghi-Siyan grew desperate, executing Christian inhabitants and fortifying the citadel.

By May, betrayal brewed. Bohemond bribed an Armenian guard named Firouz, who controlled the Tower of the Two Sisters. On June 2, Firouz lowered ropes; Crusaders scaled the walls, opening gates for a massacre. Thousands of Turks died in the frenzy—Yaghi-Siyan fled but was beheaded by peasants. His son held the citadel briefly. But joy was short-lived: on June 5, a massive army under Kerbogha of Mosul arrived, besieging the besiegers. Starvation returned; visions of the Holy Lance (unearthed by Peter Bartholomew) rallied spirits. On June 28, the Crusaders sallied out in the Battle of Antioch proper, routing Kerbogha with reported angelic aid. The Lake battle's ripple effects were profound. It crippled Aleppo's power—Radwan never fully recovered, dying in 1113 amid family feuds. The Artuqids shifted focus eastward. For the Crusade, it proved European heavy cavalry's edge in charges, influencing tactics at Ascalon and Arsuf. Antioch became a Crusader principality under Bohemond, a buffer state lasting until 1268. Culturally, it fueled chansons de geste—epic poems glorifying knights like Bohemond, blending fact with myth. Chroniclers like the Gesta Francorum author (likely a Norman knight) immortalized it, shaping Western views of holy war.

Zoom out: the First Crusade reshaped the Middle East. Jerusalem fell in 1099, birthing kingdoms that endured two centuries. But it sowed seeds of jihad—Saladin's reconquests in the 1180s echoed Antioch's lessons. Economically, it boosted Italian trade via Antioch's port. Religiously, it deepened East-West schisms, especially after the 1204 sack of Constantinople.

Yet, humor lurks in the absurdity. Imagine knights on donkeys charging elites—medieval Monty Python. Or Radwan's scouts napping, dooming an empire. Bohemond, ever the opportunist, parlayed victory into a princedom, proving ambition trumps piety. The siege's horrors—eating shoes, cannibalism rumors—highlight human resilience amid folly.

Fast-forward 900 years: what can this dusty clash teach us? The Lake of Antioch wasn't just swords and shields; it was about outsmarting odds, leading boldly, and turning crises into triumphs. Here's how to channel that Crusader spirit into your daily grind.

- **Embrace the Ambush Mindset**: Like Bohemond's night march, surprise your challenges. Stuck in a rut at work? Launch a "stealth project"—brainstorm ideas after hours, present them unexpectedly to wow your boss.

- **Reserve Your Strength**: Bohemond held back squadrons for the kill shot. In life, don't burn out early—save energy for pivotal moments, like pacing a marathon or holding off on big decisions until facts align.

- **Turn Scarcity into Strategy**: With few horses, Crusaders improvised. Facing limited resources? Get creative—repurpose skills, network frugally, or bootstrap a side hustle with what you have.

- **Build Alliances Wisely**: Radwan's coalition crumbled; Crusaders united under one leader. Forge teams that endure—choose collaborators who share your vision, not just convenience.

- **Celebrate Small Wins**: Post-battle heads on pikes? Gruesome, but symbolic. Mark your victories—journal successes, treat yourself after goals, to build momentum.

The Lake battle's ripple effects were profound. It crippled Aleppo's power—Radwan never fully recovered, dying in 1113 amid family feuds. The Artuqids shifted focus eastward. For the Crusade, it proved European heavy cavalry's edge in charges, influencing tactics at Ascalon and Arsuf. Antioch became a Crusader principality under Bohemond, a buffer state lasting until 1268. Culturally, it fueled chansons de geste—epic poems glorifying knights like Bohemond, blending fact with myth. Chroniclers like the Gesta Francorum author (likely a Norman knight) immortalized it, shaping Western views of holy war.

Zoom out: the First Crusade reshaped the Middle East. Jerusalem fell in 1099, birthing kingdoms that endured two centuries. But it sowed seeds of jihad—Saladin's reconquests in the 1180s echoed Antioch's lessons. Economically, it boosted Italian trade via Antioch's port. Religiously, it deepened East-West schisms, especially after the 1204 sack of Constantinople.

Yet, humor lurks in the absurdity. Imagine knights on donkeys charging elites—medieval Monty Python. Or Radwan's scouts napping, dooming an empire. Bohemond, ever the opportunist, parlayed victory into a princedom, proving ambition trumps piety. The siege's horrors—eating shoes, cannibalism rumors—highlight human resilience amid folly.

Fast-forward 900 years: what can this dusty clash teach us? The Lake of Antioch wasn't just swords and shields; it was about outsmarting odds, leading boldly, and turning crises into triumphs. Here's how to channel that Crusader spirit into your daily grind.

- **Embrace the Ambush Mindset**: Like Bohemond's night march, surprise your challenges. Stuck in a rut at work? Launch a "stealth project"—brainstorm ideas after hours, present them unexpectedly to wow your boss.

- **Reserve Your Strength**: Bohemond held back squadrons for the kill shot. In life, don't burn out early—save energy for pivotal moments, like pacing a marathon or holding off on big decisions until facts align.

- **Turn Scarcity into Strategy**: With few horses, Crusaders improvised. Facing limited resources? Get creative—repurpose skills, network frugally, or bootstrap a side hustle with what you have.

- **Build Alliances Wisely**: Radwan's coalition crumbled; Crusaders united under one leader. Forge teams that endure—choose collaborators who share your vision, not just convenience.

- **Celebrate Small Wins**: Post-battle heads on pikes? Gruesome, but symbolic. Mark your victories—journal successes, treat yourself after goals, to build momentum. Now, a 30-day plan to apply this:

Now, a 30-day plan to apply this:

**Days 1-7: Scout the Terrain**: Assess your "siege"—identify a personal goal (e.g., career shift, fitness). Research obstacles like Bohemond's scouts; journal daily insights.

**Days 8-14: Assemble Your Squadrons**: Gather resources—books, mentors, tools. Divide tasks into "forward" (immediate actions) and "reserves" (backup plans). Take one bold step, like networking.

**Days 15-21: Launch the Ambush**: Execute a surprise move—apply for that job, start a habit streak. Adapt to pushback, channeling Crusader grit.

**Days 22-28: Secure the Victory**: Review progress, celebrate wins. Adjust for setbacks, like repelling a "sortie" (distractions).

**Days 29-30: Reflect and Reinforce**: Analyze outcomes; plan the next "crusade." Motivate by sharing your story—because if 700 knights can defy 12,000, you can conquer your lake.

There you have it—a tale of medieval mayhem that's equal parts education and inspiration. The Lake of Antioch reminds us: history isn't dead; it's a playbook for the bold. Go forth and charge!

The siege kicked off on October 21, 1097. The Crusaders, numbering around 40,000 at the start (including non-combatants), encircled the city but couldn't fully blockade it due to its size and terrain. Yaghi-Siyan, the wily Turkish governor, had stocked up on supplies and commanded a garrison of several thousand. He played a smart game: harassing the besiegers with sorties, poisoning wells, and sending pleas for help to neighboring emirs. The Crusaders, meanwhile, built makeshift forts like Malregard and Tancred's Tower to tighten the noose, but winter hit hard. Rain turned camps into swamps, food ran scarce, and dysentery ravaged the ranks. Horses died by the hundreds—vital for the knights' shock tactics—leaving many to ride donkeys or oxen. Morale plummeted; deserters fled, including high-profile ones like Peter the Hermit, who was dragged back in chains. By December, things got dire. A foraging party under Bohemond and Robert II of Flanders clashed with a relief force from Damascus led by Duqaq at the Battle of Harenc on December 31. The Crusaders won, but barely, capturing precious supplies. Yaghi-Siyan, undeterred, dispatched his son Shams ad-Daulah to rally more aid. Shams first hit up Duqaq, who was licking his wounds and declined. Undaunted, he headed to Aleppo, where Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan ruled. Radwan, a Seljuq sultan in his early 20s, had just patched up a feud with his brother Duqaq—sibling rivalries were as common in medieval Islam as they were explosive. Seeing a chance to boost his prestige, Radwan assembled a coalition: his own Aleppan troops, Artuqid allies under Soqman ibn Ortoq, and forces from Hamah. By early February 1098, this army—estimated at 12,000 strong, including archers, light cavalry, and infantry—camped at Harim, just 35 kilometers east of Antioch.

Word reached the Crusader camp via scouts and spies. Panic ensued. The leaders—Bohemond, Raymond, Godfrey, Robert of Flanders, and others—debated furiously. A full-scale assault from Radwan could pin them against Antioch's walls, with Yaghi-Siyan's garrison sallying out for a pincer move. Starvation had whittled their effective knights to about 700, a fraction of their original cavalry. In a bold move, they elected Bohemond as supreme commander for this crisis—the first time the Crusade had a unified leader. Bohemond, a towering Norman with a reputation for cunning (he'd fought Byzantines and Turks before), rejected a static defense at the Iron Bridge over the Orontes. That would invite attrition, playing to Radwan's numbers. Instead, he gambled on offense: a night march to ambush the relief force in a narrow defile between the river and the Lake of Antioch (modern Lake Amik, a marshy basin prone to flooding). Under moonless skies on February 8, Bohemond's knights slipped across the Iron Bridge undetected. Muslim scouts watched by day but slacked off at night—classic overconfidence. The Crusaders rode east along the Aleppo road, hugging the Orontes on their left. Dawn broke on February 9 as they reached a hilly spot ideal for ambush: the terrain funneled enemies into a bottleneck, negating superior numbers. Bohemond divided his force into seven squadrons—five forward under leaders like Robert of Flanders, Tancred (Bohemond's nephew), and Adhemar of Le Puy (the papal legate, more spiritual than martial), with Bohemond holding the sixth and seventh in reserve. It was a classic feigned retreat setup, straight out of Norman playbook. Radwan's army approached leisurely, unaware of the trap. He led with two vanguard squadrons screening the main body—archers on horseback, light lancers, and infantry. As they neared the hill, Bohemond sprang the ambush. The five forward squadrons charged downhill, lances couched, slamming into the Turkish flank. The impact was devastating: the vanguard crumpled, retreating into the deploying main force and sowing confusion. Arrows flew thick as the Turks regrouped, their horse archers peppering the knights. The Crusaders, armored in chainmail hauberks and conical helmets, absorbed the barrage but began to falter under sheer volume. Knights dismounted to fight on foot when horses failed, turning the melee into a brutal slog. Here's where Bohemond's genius shone. Sensing the tipping point, he committed his reserves—fresh knights thundering in for the knockout blow. The charge shattered the Turkish center; panic spread like wildfire. Radwan's coalition fractured—Artuqids fled first, then others. The rout was total: Crusaders pursued for miles, hacking down fugitives and seizing baggage trains loaded with food, weapons, and horses. Back at Antioch, Yaghi-Siyan timed a sortie to hit the Crusader camp, but Raymond of Toulouse repelled it with infantry and crossbowmen. By midday, the battle was over. Crusader losses were minimal—perhaps a few dozen knights—while Radwan's army lost thousands, including key officers. Heads of the slain were paraded on pikes back to camp, a gruesome morale booster.

The immediate aftermath was electric. The captured supplies—grain, livestock, tents—alleviated the siege's famine. Morale skyrocketed; deserters reconsidered. Bohemond's stock rose—he claimed Antioch as his prize, setting up future squabbles with Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who wanted the city back. But the siege dragged on. In March, an English fleet under Edgar Atheling docked at St. Symeon pier, bringing reinforcements and siege engines. Yaghi-Siyan grew desperate, executing Christian inhabitants and fortifying the citadel. By May, betrayal brewed. Bohemond bribed an Armenian guard named Firouz, who controlled the Tower of the Two Sisters. On June 2, Firouz lowered ropes; Crusaders scaled the walls, opening gates for a massacre. Thousands of Turks died in the frenzy—Yaghi-Siyan fled but was beheaded by peasants. His son held the citadel briefly. But joy was short-lived: on June 5, a massive army under Kerbogha of Mosul arrived, besieging the besiegers. Starvation returned; visions of the Holy Lance (unearthed by Peter Bartholomew) rallied spirits. On June 28, the Crusaders sallied out in the Battle of Antioch proper, routing Kerbogha with reported angelic aid.

The Lake battle's ripple effects were profound. It crippled Aleppo's power—Radwan never fully recovered, dying in 1113 amid family feuds. The Artuqids shifted focus eastward. For the Crusade, it proved European heavy cavalry's edge in charges, influencing tactics at Ascalon and Arsuf. Antioch became a Crusader principality under Bohemond, a buffer state lasting until 1268. Culturally, it fueled chansons de geste—epic poems glorifying knights like Bohemond, blending fact with myth. Chroniclers like the Gesta Francorum author (likely a Norman knight) immortalized it, shaping Western views of holy war. Zoom out: the First Crusade reshaped the Middle East. Jerusalem fell in 1099, birthing kingdoms that endured two centuries. But it sowed seeds of jihad—Saladin's reconquests in the 1180s echoed Antioch's lessons. Economically, it boosted Italian trade via Antioch's port. Religiously, it deepened East-West schisms, especially after the 1204 sack of Constantinople. Yet, humor lurks in the absurdity. Imagine knights on donkeys charging elites—medieval Monty Python. Or Radwan's scouts napping, dooming an empire. Bohemond, ever the opportunist, parlayed victory into a princedom, proving ambition trumps piety. The siege's horrors—eating shoes, cannibalism rumors—highlight human resilience amid folly. Fast-forward 900 years: what can this dusty clash teach us? The Lake of Antioch wasn't just swords and shields; it was about outsmarting odds, leading boldly, and turning crises into triumphs. Here's how to channel that Crusader spirit into your daily grind. - **Embrace the Ambush Mindset**: Like Bohemond's night march, surprise your challenges. Stuck in a rut at work? Launch a "stealth project"—brainstorm ideas after hours, present them unexpectedly to wow your boss. - **Reserve Your Strength**: Bohemond held back squadrons for the kill shot. In life, don't burn out early—save energy for pivotal moments, like pacing a marathon or holding off on big decisions until facts align. - **Turn Scarcity into Strategy**: With few horses, Crusaders improvised. Facing limited resources? Get creative—repurpose skills, network frugally, or bootstrap a side hustle with what you have. - **Build Alliances Wisely**: Radwan's coalition crumbled; Crusaders united under one leader. Forge teams that endure—choose collaborators who share your vision, not just convenience. - **Celebrate Small Wins**: Post-battle heads on pikes? Gruesome, but symbolic. Mark your victories—journal successes, treat yourself after goals, to build momentum.

Now, a 30-day plan to apply this: