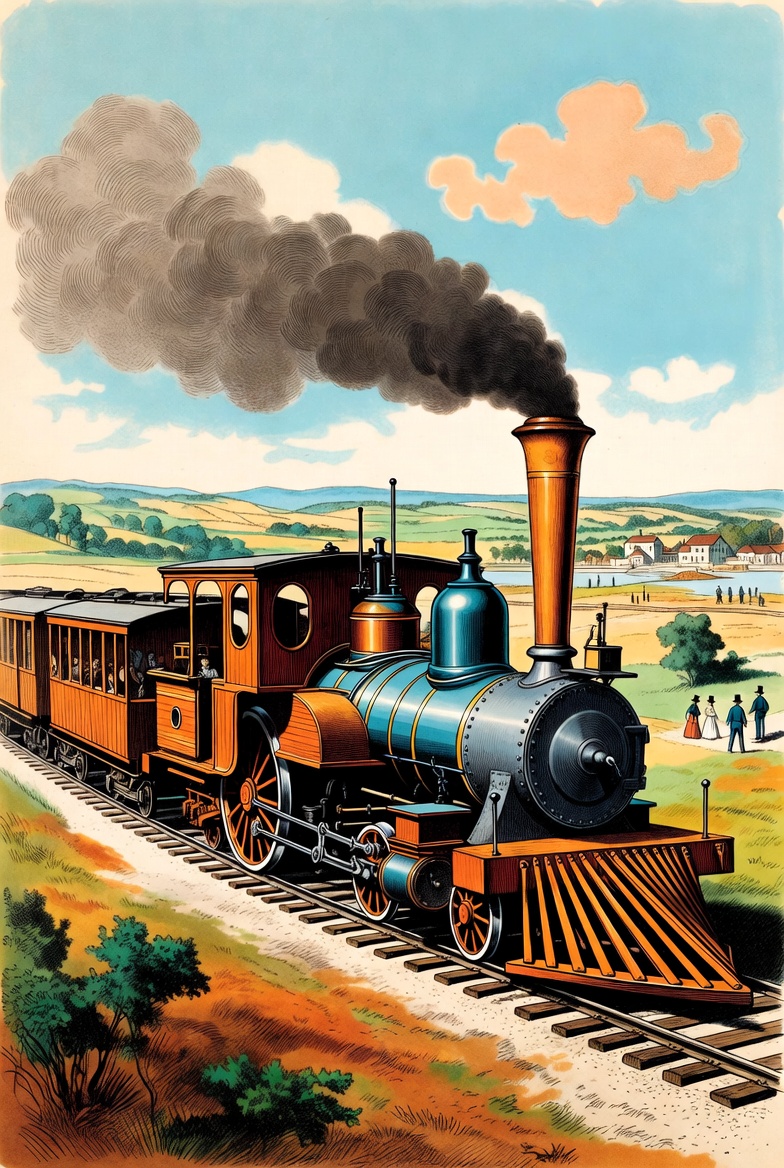

Picture this: It's 1815, America is barely catching its breath after the War of 1812 – that messy sequel to the Revolution where we tangled with the British again over trade, impressment, and a side of territorial ambition. The young nation is a patchwork of dirt roads, sluggish canals, and rivers that only flow where Mother Nature deems fit. Horses are the kings of transport, pulling wagons at a blistering 4 miles per hour on a good day, and stagecoaches are basically wooden boxes on wheels that rattle your teeth loose over potholes the size of small craters. Enter John Stevens, a Hoboken inventor with a steamboat obsession and a vision that could make even the most skeptical farmer raise an eyebrow. On February 6, 1815, the New Jersey legislature grants him the first railroad charter in American history – a seemingly mundane piece of paper that would unleash the iron horse and transform the continent into a web of steel rails. This isn't just some dusty footnote; it's the spark that lit the fuse for the railroad boom, reshaping economies, societies, and even the way we think about progress. Buckle up (or hitch your wagon), because we're diving deep into this pivotal moment – with a dash of humor to keep things from derailing – and then we'll chug into how this ancient act of innovation can supercharge your life today. Let's rewind the clock to understand why this charter mattered. The early 1800s were a time of explosive growth for the United States. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 had doubled the country's size overnight, adding vast territories west of the Mississippi that screamed potential but whispered isolation. How do you connect bustling East Coast ports like New York and Philadelphia to the fertile Ohio Valley or the untamed frontier? Roads were abysmal – the National Road, started in 1811, was a glorified mud path that took years to build and even longer to traverse. Canals were the hot new thing, inspired by Europe's successes and America's own Erie Canal dreams (which wouldn't open until 1825). But canals required flat land, massive digging, and a reliable water supply – not exactly abundant in hilly New Jersey or the rugged Appalachians.

John Stevens, born in 1749 to a wealthy New York family, was no stranger to tinkering with transportation. His father was a merchant and politician, giving young John a front-row seat to the colonies' economic woes. After studying law at King's College (now Columbia University), Stevens dove into engineering during the Revolution, serving as a treasurer for New Jersey and experimenting with steam power. By the early 1800s, he was all-in on steamboats. In 1807, his Phoenix became the first steam-powered vessel to sail the open ocean, chugging from New York to Philadelphia via the Delaware River – a feat that bypassed Robert Fulton's more famous Clermont on the Hudson. But Stevens wasn't content with water; he saw steam's potential on land. Influenced by British inventors like Richard Trevithick, who built the world's first steam locomotive in 1804, Stevens petitioned the New Jersey legislature in 1811 for a railroad charter. They laughed it off – who needs iron tracks when horses do just fine?

Let's rewind the clock to understand why this charter mattered. The early 1800s were a time of explosive growth for the United States. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 had doubled the country's size overnight, adding vast territories west of the Mississippi that screamed potential but whispered isolation. How do you connect bustling East Coast ports like New York and Philadelphia to the fertile Ohio Valley or the untamed frontier? Roads were abysmal – the National Road, started in 1811, was a glorified mud path that took years to build and even longer to traverse. Canals were the hot new thing, inspired by Europe's successes and America's own Erie Canal dreams (which wouldn't open until 1825). But canals required flat land, massive digging, and a reliable water supply – not exactly abundant in hilly New Jersey or the rugged Appalachians.

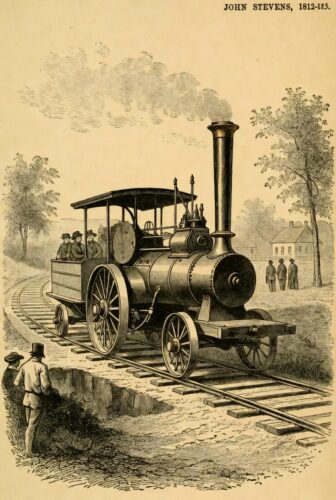

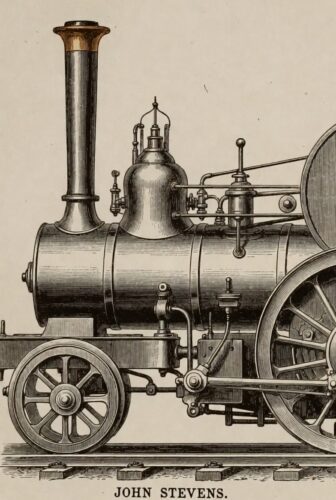

John Stevens, born in 1749 to a wealthy New York family, was no stranger to tinkering with transportation. His father was a merchant and politician, giving young John a front-row seat to the colonies' economic woes. After studying law at King's College (now Columbia University), Stevens dove into engineering during the Revolution, serving as a treasurer for New Jersey and experimenting with steam power. By the early 1800s, he was all-in on steamboats. In 1807, his Phoenix became the first steam-powered vessel to sail the open ocean, chugging from New York to Philadelphia via the Delaware River – a feat that bypassed Robert Fulton's more famous Clermont on the Hudson. But Stevens wasn't content with water; he saw steam's potential on land. Influenced by British inventors like Richard Trevithick, who built the world's first steam locomotive in 1804, Stevens petitioned the New Jersey legislature in 1811 for a railroad charter. They laughed it off – who needs iron tracks when horses do just fine? Undeterred, Stevens published a pamphlet in 1812 titled "Documents Tending to Prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-Ways and Steam-Carriages over Canal Navigation." It was a manifesto of sorts, arguing that railroads could climb hills, operate year-round (no freezing canals in winter), and haul goods faster and cheaper. He calculated costs meticulously: a single-track railroad from Trenton to New Brunswick (about 27 miles) would cost around $300,000, versus millions for a canal. Stevens even built a small experimental track on his Hoboken estate in 1812, where a steam engine pulled a carriage at – wait for it – a whopping 4 mph. It was clunky, smoky, and probably scared the local cows, but it proved the concept. Imagine the neighbors peeking over fences, wondering if this mad inventor was summoning demons or just burning coal for fun.

The War of 1812 changed everything. British blockades crippled coastal shipping, forcing goods overland at exorbitant costs. Suddenly, internal improvements weren't a luxury; they were a necessity for national security and economic survival. New Jersey, sandwiched between Philadelphia and New York, was prime real estate for a shortcut. Stevens lobbied hard, emphasizing how a railroad could link the Delaware and Raritan rivers, bypassing the treacherous Atlantic swells around Cape May. On February 6, 1815, the legislature finally bit. The charter incorporated the New Jersey Railroad Company, granting Stevens and his associates exclusive rights to build a line from the Delaware River near Trenton to the Raritan River near New Brunswick. It allowed for wooden or iron rails, horse or steam power, and even tolls for usage – think of it as the world's first railroad franchise.

But here's where the story gets hilariously human: Stevens couldn't raise the money. Investors balked at the unproven technology. "Rails? Steam? Sounds like a fairy tale," they probably muttered while sipping their ale. The charter lapsed in 1817 without a single spike driven. Stevens, ever the optimist, got an extension and kept pushing. By 1823, he convinced Pennsylvania to charter a similar line from Philadelphia to Columbia on the Susquehanna River – another first, though that one also stalled. It wasn't until 1830 that his sons, Robert and Edwin, revived the idea with the Camden and Amboy Railroad, which finally built the Trenton-New Brunswick line using the 1815 charter as a blueprint. Robert Stevens even invented the T-rail – that iconic railroad track shape still used today – while doodling on a ship to England in 1830.

The 1815 charter's ripple effects were enormous. It set legal precedents for incorporating railroads, eminent domain for land acquisition, and state monopolies to encourage investment. By the 1830s, railroads exploded across America. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, chartered in 1827, laid its first tracks in 1828. The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company ran the first scheduled steam train in 1830 with the "Best Friend of Charleston" – which, in a comedic tragedy, exploded in 1831 when a fireman sat on the safety valve to quiet the hissing. (Lesson: Don't mess with steam pressure.) By 1840, the U.S. had over 2,800 miles of track, surpassing Britain's total. Railroads slashed travel times: What took weeks by wagon now took days. Goods flooded markets – cotton from the South to Northern mills, grain from the Midwest to Eastern ports.

Undeterred, Stevens published a pamphlet in 1812 titled "Documents Tending to Prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-Ways and Steam-Carriages over Canal Navigation." It was a manifesto of sorts, arguing that railroads could climb hills, operate year-round (no freezing canals in winter), and haul goods faster and cheaper. He calculated costs meticulously: a single-track railroad from Trenton to New Brunswick (about 27 miles) would cost around $300,000, versus millions for a canal. Stevens even built a small experimental track on his Hoboken estate in 1812, where a steam engine pulled a carriage at – wait for it – a whopping 4 mph. It was clunky, smoky, and probably scared the local cows, but it proved the concept. Imagine the neighbors peeking over fences, wondering if this mad inventor was summoning demons or just burning coal for fun.

The War of 1812 changed everything. British blockades crippled coastal shipping, forcing goods overland at exorbitant costs. Suddenly, internal improvements weren't a luxury; they were a necessity for national security and economic survival. New Jersey, sandwiched between Philadelphia and New York, was prime real estate for a shortcut. Stevens lobbied hard, emphasizing how a railroad could link the Delaware and Raritan rivers, bypassing the treacherous Atlantic swells around Cape May. On February 6, 1815, the legislature finally bit. The charter incorporated the New Jersey Railroad Company, granting Stevens and his associates exclusive rights to build a line from the Delaware River near Trenton to the Raritan River near New Brunswick. It allowed for wooden or iron rails, horse or steam power, and even tolls for usage – think of it as the world's first railroad franchise.

But here's where the story gets hilariously human: Stevens couldn't raise the money. Investors balked at the unproven technology. "Rails? Steam? Sounds like a fairy tale," they probably muttered while sipping their ale. The charter lapsed in 1817 without a single spike driven. Stevens, ever the optimist, got an extension and kept pushing. By 1823, he convinced Pennsylvania to charter a similar line from Philadelphia to Columbia on the Susquehanna River – another first, though that one also stalled. It wasn't until 1830 that his sons, Robert and Edwin, revived the idea with the Camden and Amboy Railroad, which finally built the Trenton-New Brunswick line using the 1815 charter as a blueprint. Robert Stevens even invented the T-rail – that iconic railroad track shape still used today – while doodling on a ship to England in 1830.

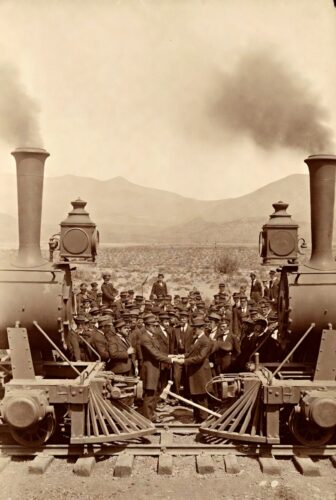

The 1815 charter's ripple effects were enormous. It set legal precedents for incorporating railroads, eminent domain for land acquisition, and state monopolies to encourage investment. By the 1830s, railroads exploded across America. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, chartered in 1827, laid its first tracks in 1828. The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company ran the first scheduled steam train in 1830 with the "Best Friend of Charleston" – which, in a comedic tragedy, exploded in 1831 when a fireman sat on the safety valve to quiet the hissing. (Lesson: Don't mess with steam pressure.) By 1840, the U.S. had over 2,800 miles of track, surpassing Britain's total. Railroads slashed travel times: What took weeks by wagon now took days. Goods flooded markets – cotton from the South to Northern mills, grain from the Midwest to Eastern ports. Zoom in on the economic boom. Railroads fueled the Market Revolution, turning subsistence farming into cash-crop empires. In the Midwest, lines like the Erie Railroad (completed in 1851) connected the Great Lakes to the Hudson, making New York the nation's commercial hub. Chicago, a swampy outpost in 1830, became a rail nexus by 1850 with 11 lines converging, handling millions of bushels of wheat. The transcontinental railroad, finished in 1869 with that golden spike at Promontory Summit, shrank the continent from months to days, enabling Manifest Destiny's westward rush. But it wasn't all rosy: Railroads displaced Native American lands, with lines like the Union Pacific carving through Sioux territory, leading to conflicts like the Bozeman Trail wars.

Socially, railroads were a mixed bag of wonder and woe. They democratized travel – the rich in first-class cars with velvet seats, the poor in wooden benches amid livestock smells. Mark Twain quipped about the discomfort: "Nothing helps scenery like ham and eggs." Accidents were rampant; boilers exploded, bridges collapsed, and cows wandered onto tracks, inspiring the cowcatcher invention. The 1830s saw the first railroad riots, like in Philadelphia where workers protested low wages. Yet, railroads birthed time zones in 1883 to standardize schedules – before that, every town had its own "sun time," leading to chaotic timetables.

Culturally, the iron horse inspired awe and art. Walt Whitman waxed poetic in "To a Locomotive in Winter": "Thy black cylindric body, golden brass and silvery steel." Songs like "I've Been Working on the Railroad" captured the labor, while dime novels romanticized train robbers like Jesse James, who derailed his first train in 1873. Railroads even influenced language – "off the rails" for madness, "train of thought" for ideas chugging along.

Zoom in on the economic boom. Railroads fueled the Market Revolution, turning subsistence farming into cash-crop empires. In the Midwest, lines like the Erie Railroad (completed in 1851) connected the Great Lakes to the Hudson, making New York the nation's commercial hub. Chicago, a swampy outpost in 1830, became a rail nexus by 1850 with 11 lines converging, handling millions of bushels of wheat. The transcontinental railroad, finished in 1869 with that golden spike at Promontory Summit, shrank the continent from months to days, enabling Manifest Destiny's westward rush. But it wasn't all rosy: Railroads displaced Native American lands, with lines like the Union Pacific carving through Sioux territory, leading to conflicts like the Bozeman Trail wars.

Socially, railroads were a mixed bag of wonder and woe. They democratized travel – the rich in first-class cars with velvet seats, the poor in wooden benches amid livestock smells. Mark Twain quipped about the discomfort: "Nothing helps scenery like ham and eggs." Accidents were rampant; boilers exploded, bridges collapsed, and cows wandered onto tracks, inspiring the cowcatcher invention. The 1830s saw the first railroad riots, like in Philadelphia where workers protested low wages. Yet, railroads birthed time zones in 1883 to standardize schedules – before that, every town had its own "sun time," leading to chaotic timetables.

Culturally, the iron horse inspired awe and art. Walt Whitman waxed poetic in "To a Locomotive in Winter": "Thy black cylindric body, golden brass and silvery steel." Songs like "I've Been Working on the Railroad" captured the labor, while dime novels romanticized train robbers like Jesse James, who derailed his first train in 1873. Railroads even influenced language – "off the rails" for madness, "train of thought" for ideas chugging along. Politically, the charter highlighted federalism's tensions. States initially led infrastructure, but by the 1850s, Congress got involved with land grants for lines like the Illinois Central, which Abraham Lincoln helped charter as a lawyer. The Civil War showcased railroads' strategic might: The Union's superior network moved troops and supplies efficiently, while the Confederacy's fragmented lines contributed to its downfall. Gettysburg might have turned differently without the timely arrival of Union reinforcements via rail.

Fast-forward to the Gilded Age: Railroads monopolized by tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, who bought up lines like the New York Central, amassing fortunes while crushing competition. The 1877 Great Railroad Strike, sparked by wage cuts, saw riots from Baltimore to San Francisco, foreshadowing labor movements. Regulation followed with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the first federal oversight of private industry.

Stevens' legacy? He died in 1838, just as railroads took off, but his Hoboken estate became the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1870 – still churning out engineers. The Camden and Amboy, completed in 1834, carried President Andrew Jackson in 1833, who reportedly said, "It's faster than a fox chase!" By then, steam locomotives like the John Bull (imported from England in 1831) were pulling trains at 25 mph, a speed that made passengers dizzy and hats fly off.

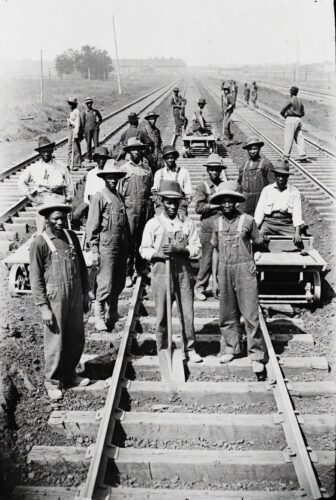

The 1815 charter wasn't built upon immediately, but it planted the seed. Without it, the railroad era might have delayed, stunting America's industrial leap. By 1900, the U.S. had 193,000 miles of track – more than the rest of the world combined. It connected coasts, fueled factories, and turned immigrants into nation-builders, like the Chinese workers on the Central Pacific who blasted through Sierra granite with nitroglycerin (explosive stuff, literally).

Humor peppered the era: Early critics called railroads "devices of Satan," fearing they'd scare animals or cause miscarriages from vibrations. One Ohio school board in 1828 banned railroad info, claiming trains were "impossible" over 12 mph because passengers couldn't breathe. Stevens himself demonstrated his Hoboken loop to skeptics, who rode it wide-eyed, probably thinking, "This beats walking!"

Politically, the charter highlighted federalism's tensions. States initially led infrastructure, but by the 1850s, Congress got involved with land grants for lines like the Illinois Central, which Abraham Lincoln helped charter as a lawyer. The Civil War showcased railroads' strategic might: The Union's superior network moved troops and supplies efficiently, while the Confederacy's fragmented lines contributed to its downfall. Gettysburg might have turned differently without the timely arrival of Union reinforcements via rail.

Fast-forward to the Gilded Age: Railroads monopolized by tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, who bought up lines like the New York Central, amassing fortunes while crushing competition. The 1877 Great Railroad Strike, sparked by wage cuts, saw riots from Baltimore to San Francisco, foreshadowing labor movements. Regulation followed with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the first federal oversight of private industry.

Stevens' legacy? He died in 1838, just as railroads took off, but his Hoboken estate became the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1870 – still churning out engineers. The Camden and Amboy, completed in 1834, carried President Andrew Jackson in 1833, who reportedly said, "It's faster than a fox chase!" By then, steam locomotives like the John Bull (imported from England in 1831) were pulling trains at 25 mph, a speed that made passengers dizzy and hats fly off.

The 1815 charter wasn't built upon immediately, but it planted the seed. Without it, the railroad era might have delayed, stunting America's industrial leap. By 1900, the U.S. had 193,000 miles of track – more than the rest of the world combined. It connected coasts, fueled factories, and turned immigrants into nation-builders, like the Chinese workers on the Central Pacific who blasted through Sierra granite with nitroglycerin (explosive stuff, literally).

Humor peppered the era: Early critics called railroads "devices of Satan," fearing they'd scare animals or cause miscarriages from vibrations. One Ohio school board in 1828 banned railroad info, claiming trains were "impossible" over 12 mph because passengers couldn't breathe. Stevens himself demonstrated his Hoboken loop to skeptics, who rode it wide-eyed, probably thinking, "This beats walking!" The charter's details were straightforward: Capital stock of $1 million, shares at $100 each, construction within three years (which didn't happen). It allowed for branches and even ferries – Stevens' steamboat nod. But its true genius was exclusivity: No competing lines for 14 years, enticing investors with monopoly profits.

In the broader context, 1815 was a pivotal year. The Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 on Christmas Eve 1814, but news traveled slow – Andrew Jackson won New Orleans on January 8, 1815, unaware of peace. Napoleon escaped Elba in March, leading to Waterloo in June. America, buoyed by "victory," turned inward to build. The charter symbolized that shift: From wartime survival to peacetime innovation.

Railroads' environmental impact? They devoured forests for ties and fuel, but also preserved them by replacing wood with coal. They spread invasive species via ballast but enabled national parks by tourism, like Yellowstone in 1872.

By the 20th century, autos and planes eclipsed trains, but freight rails still haul 40% of U.S. goods. High-speed dreams persist, like California's bullet train saga – echoing Stevens' funding woes.

This 1815 spark ignited a revolution that stitched America together, for better or worse. It showed how one bold idea, chartered on a winter day, could propel a nation forward at breakneck speed.

Now, how does this dusty charter benefit you today? In a world of gig economies, AI disruptions, and endless side hustles, Stevens' perseverance offers timeless tracks to success. Here's how to apply it personally:

- **Embrace Innovation in Everyday Challenges**: Just as Stevens pivoted from steamboats to rails, scan your routine for upgrades. Bullet point plan: Identify one outdated habit (e.g., manual budgeting), research modern tools (apps like Mint), implement weekly (track expenses Sundays), review monthly for savings – aim for 10% budget cut in three months.

- **Persist Through Rejections**: Stevens' 1811 flop didn't stop him; he refined and returned. In your career, treat "no" as "not yet." Plan: After a job rejection, analyze feedback, update resume with one new skill (e.g., learn Python via free Codecademy course, 2 hours/week), network on LinkedIn (connect with 5 pros weekly), reapply to similar roles quarterly – target promotion or raise in six months.

- **Build Networks Like Rail Lines**: Railroads connected isolated towns; connect your skills to opportunities. Plan: Map your "network tracks" – list 10 contacts, reach out monthly with value (share articles), join one group (e.g., local Toastmasters), host a virtual coffee chat biweekly – grow to 50 meaningful connections in a year, opening doors to collaborations.

- **Calculate Risks with Data**: Stevens' pamphlet crunched numbers; do the same for decisions. Plan: For a side hustle (e.g., freelancing), estimate costs/revenue (spreadsheet: $500 startup, $200/month goal), test small (one client via Upwork), scale if profitable (add marketing after three months) – achieve break-even in quarter one, profit in quarter two.

- **Adapt to Changing Landscapes**: Railroads conquered hills; adapt to life's obstacles. Plan: Face a setback (e.g., health issue), research solutions (apps like MyFitnessPal), set milestones (walk 10k steps daily), adjust as needed (switch to yoga if needed), celebrate wins weekly – regain momentum in 30 days.

Follow this six-month plan: Months 1-2 focus on innovation and persistence (daily journaling wins), 3-4 on networking and risks (monthly reviews), 5-6 on adaptation (quarterly goals reset). Like Stevens' charter, your small start can lead to massive momentum – chug on!

The charter's details were straightforward: Capital stock of $1 million, shares at $100 each, construction within three years (which didn't happen). It allowed for branches and even ferries – Stevens' steamboat nod. But its true genius was exclusivity: No competing lines for 14 years, enticing investors with monopoly profits.

In the broader context, 1815 was a pivotal year. The Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 on Christmas Eve 1814, but news traveled slow – Andrew Jackson won New Orleans on January 8, 1815, unaware of peace. Napoleon escaped Elba in March, leading to Waterloo in June. America, buoyed by "victory," turned inward to build. The charter symbolized that shift: From wartime survival to peacetime innovation.

Railroads' environmental impact? They devoured forests for ties and fuel, but also preserved them by replacing wood with coal. They spread invasive species via ballast but enabled national parks by tourism, like Yellowstone in 1872.

By the 20th century, autos and planes eclipsed trains, but freight rails still haul 40% of U.S. goods. High-speed dreams persist, like California's bullet train saga – echoing Stevens' funding woes.

This 1815 spark ignited a revolution that stitched America together, for better or worse. It showed how one bold idea, chartered on a winter day, could propel a nation forward at breakneck speed.

Now, how does this dusty charter benefit you today? In a world of gig economies, AI disruptions, and endless side hustles, Stevens' perseverance offers timeless tracks to success. Here's how to apply it personally:

- **Embrace Innovation in Everyday Challenges**: Just as Stevens pivoted from steamboats to rails, scan your routine for upgrades. Bullet point plan: Identify one outdated habit (e.g., manual budgeting), research modern tools (apps like Mint), implement weekly (track expenses Sundays), review monthly for savings – aim for 10% budget cut in three months.

- **Persist Through Rejections**: Stevens' 1811 flop didn't stop him; he refined and returned. In your career, treat "no" as "not yet." Plan: After a job rejection, analyze feedback, update resume with one new skill (e.g., learn Python via free Codecademy course, 2 hours/week), network on LinkedIn (connect with 5 pros weekly), reapply to similar roles quarterly – target promotion or raise in six months.

- **Build Networks Like Rail Lines**: Railroads connected isolated towns; connect your skills to opportunities. Plan: Map your "network tracks" – list 10 contacts, reach out monthly with value (share articles), join one group (e.g., local Toastmasters), host a virtual coffee chat biweekly – grow to 50 meaningful connections in a year, opening doors to collaborations.

- **Calculate Risks with Data**: Stevens' pamphlet crunched numbers; do the same for decisions. Plan: For a side hustle (e.g., freelancing), estimate costs/revenue (spreadsheet: $500 startup, $200/month goal), test small (one client via Upwork), scale if profitable (add marketing after three months) – achieve break-even in quarter one, profit in quarter two.

- **Adapt to Changing Landscapes**: Railroads conquered hills; adapt to life's obstacles. Plan: Face a setback (e.g., health issue), research solutions (apps like MyFitnessPal), set milestones (walk 10k steps daily), adjust as needed (switch to yoga if needed), celebrate wins weekly – regain momentum in 30 days.

Follow this six-month plan: Months 1-2 focus on innovation and persistence (daily journaling wins), 3-4 on networking and risks (monthly reviews), 5-6 on adaptation (quarterly goals reset). Like Stevens' charter, your small start can lead to massive momentum – chug on!

Let's rewind the clock to understand why this charter mattered. The early 1800s were a time of explosive growth for the United States. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 had doubled the country's size overnight, adding vast territories west of the Mississippi that screamed potential but whispered isolation. How do you connect bustling East Coast ports like New York and Philadelphia to the fertile Ohio Valley or the untamed frontier? Roads were abysmal – the National Road, started in 1811, was a glorified mud path that took years to build and even longer to traverse. Canals were the hot new thing, inspired by Europe's successes and America's own Erie Canal dreams (which wouldn't open until 1825). But canals required flat land, massive digging, and a reliable water supply – not exactly abundant in hilly New Jersey or the rugged Appalachians. John Stevens, born in 1749 to a wealthy New York family, was no stranger to tinkering with transportation. His father was a merchant and politician, giving young John a front-row seat to the colonies' economic woes. After studying law at King's College (now Columbia University), Stevens dove into engineering during the Revolution, serving as a treasurer for New Jersey and experimenting with steam power. By the early 1800s, he was all-in on steamboats. In 1807, his Phoenix became the first steam-powered vessel to sail the open ocean, chugging from New York to Philadelphia via the Delaware River – a feat that bypassed Robert Fulton's more famous Clermont on the Hudson. But Stevens wasn't content with water; he saw steam's potential on land. Influenced by British inventors like Richard Trevithick, who built the world's first steam locomotive in 1804, Stevens petitioned the New Jersey legislature in 1811 for a railroad charter. They laughed it off – who needs iron tracks when horses do just fine?

Undeterred, Stevens published a pamphlet in 1812 titled "Documents Tending to Prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-Ways and Steam-Carriages over Canal Navigation." It was a manifesto of sorts, arguing that railroads could climb hills, operate year-round (no freezing canals in winter), and haul goods faster and cheaper. He calculated costs meticulously: a single-track railroad from Trenton to New Brunswick (about 27 miles) would cost around $300,000, versus millions for a canal. Stevens even built a small experimental track on his Hoboken estate in 1812, where a steam engine pulled a carriage at – wait for it – a whopping 4 mph. It was clunky, smoky, and probably scared the local cows, but it proved the concept. Imagine the neighbors peeking over fences, wondering if this mad inventor was summoning demons or just burning coal for fun. The War of 1812 changed everything. British blockades crippled coastal shipping, forcing goods overland at exorbitant costs. Suddenly, internal improvements weren't a luxury; they were a necessity for national security and economic survival. New Jersey, sandwiched between Philadelphia and New York, was prime real estate for a shortcut. Stevens lobbied hard, emphasizing how a railroad could link the Delaware and Raritan rivers, bypassing the treacherous Atlantic swells around Cape May. On February 6, 1815, the legislature finally bit. The charter incorporated the New Jersey Railroad Company, granting Stevens and his associates exclusive rights to build a line from the Delaware River near Trenton to the Raritan River near New Brunswick. It allowed for wooden or iron rails, horse or steam power, and even tolls for usage – think of it as the world's first railroad franchise. But here's where the story gets hilariously human: Stevens couldn't raise the money. Investors balked at the unproven technology. "Rails? Steam? Sounds like a fairy tale," they probably muttered while sipping their ale. The charter lapsed in 1817 without a single spike driven. Stevens, ever the optimist, got an extension and kept pushing. By 1823, he convinced Pennsylvania to charter a similar line from Philadelphia to Columbia on the Susquehanna River – another first, though that one also stalled. It wasn't until 1830 that his sons, Robert and Edwin, revived the idea with the Camden and Amboy Railroad, which finally built the Trenton-New Brunswick line using the 1815 charter as a blueprint. Robert Stevens even invented the T-rail – that iconic railroad track shape still used today – while doodling on a ship to England in 1830. The 1815 charter's ripple effects were enormous. It set legal precedents for incorporating railroads, eminent domain for land acquisition, and state monopolies to encourage investment. By the 1830s, railroads exploded across America. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, chartered in 1827, laid its first tracks in 1828. The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company ran the first scheduled steam train in 1830 with the "Best Friend of Charleston" – which, in a comedic tragedy, exploded in 1831 when a fireman sat on the safety valve to quiet the hissing. (Lesson: Don't mess with steam pressure.) By 1840, the U.S. had over 2,800 miles of track, surpassing Britain's total. Railroads slashed travel times: What took weeks by wagon now took days. Goods flooded markets – cotton from the South to Northern mills, grain from the Midwest to Eastern ports.

Zoom in on the economic boom. Railroads fueled the Market Revolution, turning subsistence farming into cash-crop empires. In the Midwest, lines like the Erie Railroad (completed in 1851) connected the Great Lakes to the Hudson, making New York the nation's commercial hub. Chicago, a swampy outpost in 1830, became a rail nexus by 1850 with 11 lines converging, handling millions of bushels of wheat. The transcontinental railroad, finished in 1869 with that golden spike at Promontory Summit, shrank the continent from months to days, enabling Manifest Destiny's westward rush. But it wasn't all rosy: Railroads displaced Native American lands, with lines like the Union Pacific carving through Sioux territory, leading to conflicts like the Bozeman Trail wars. Socially, railroads were a mixed bag of wonder and woe. They democratized travel – the rich in first-class cars with velvet seats, the poor in wooden benches amid livestock smells. Mark Twain quipped about the discomfort: "Nothing helps scenery like ham and eggs." Accidents were rampant; boilers exploded, bridges collapsed, and cows wandered onto tracks, inspiring the cowcatcher invention. The 1830s saw the first railroad riots, like in Philadelphia where workers protested low wages. Yet, railroads birthed time zones in 1883 to standardize schedules – before that, every town had its own "sun time," leading to chaotic timetables. Culturally, the iron horse inspired awe and art. Walt Whitman waxed poetic in "To a Locomotive in Winter": "Thy black cylindric body, golden brass and silvery steel." Songs like "I've Been Working on the Railroad" captured the labor, while dime novels romanticized train robbers like Jesse James, who derailed his first train in 1873. Railroads even influenced language – "off the rails" for madness, "train of thought" for ideas chugging along.

Politically, the charter highlighted federalism's tensions. States initially led infrastructure, but by the 1850s, Congress got involved with land grants for lines like the Illinois Central, which Abraham Lincoln helped charter as a lawyer. The Civil War showcased railroads' strategic might: The Union's superior network moved troops and supplies efficiently, while the Confederacy's fragmented lines contributed to its downfall. Gettysburg might have turned differently without the timely arrival of Union reinforcements via rail. Fast-forward to the Gilded Age: Railroads monopolized by tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, who bought up lines like the New York Central, amassing fortunes while crushing competition. The 1877 Great Railroad Strike, sparked by wage cuts, saw riots from Baltimore to San Francisco, foreshadowing labor movements. Regulation followed with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the first federal oversight of private industry. Stevens' legacy? He died in 1838, just as railroads took off, but his Hoboken estate became the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1870 – still churning out engineers. The Camden and Amboy, completed in 1834, carried President Andrew Jackson in 1833, who reportedly said, "It's faster than a fox chase!" By then, steam locomotives like the John Bull (imported from England in 1831) were pulling trains at 25 mph, a speed that made passengers dizzy and hats fly off. The 1815 charter wasn't built upon immediately, but it planted the seed. Without it, the railroad era might have delayed, stunting America's industrial leap. By 1900, the U.S. had 193,000 miles of track – more than the rest of the world combined. It connected coasts, fueled factories, and turned immigrants into nation-builders, like the Chinese workers on the Central Pacific who blasted through Sierra granite with nitroglycerin (explosive stuff, literally). Humor peppered the era: Early critics called railroads "devices of Satan," fearing they'd scare animals or cause miscarriages from vibrations. One Ohio school board in 1828 banned railroad info, claiming trains were "impossible" over 12 mph because passengers couldn't breathe. Stevens himself demonstrated his Hoboken loop to skeptics, who rode it wide-eyed, probably thinking, "This beats walking!"

The charter's details were straightforward: Capital stock of $1 million, shares at $100 each, construction within three years (which didn't happen). It allowed for branches and even ferries – Stevens' steamboat nod. But its true genius was exclusivity: No competing lines for 14 years, enticing investors with monopoly profits. In the broader context, 1815 was a pivotal year. The Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 on Christmas Eve 1814, but news traveled slow – Andrew Jackson won New Orleans on January 8, 1815, unaware of peace. Napoleon escaped Elba in March, leading to Waterloo in June. America, buoyed by "victory," turned inward to build. The charter symbolized that shift: From wartime survival to peacetime innovation. Railroads' environmental impact? They devoured forests for ties and fuel, but also preserved them by replacing wood with coal. They spread invasive species via ballast but enabled national parks by tourism, like Yellowstone in 1872. By the 20th century, autos and planes eclipsed trains, but freight rails still haul 40% of U.S. goods. High-speed dreams persist, like California's bullet train saga – echoing Stevens' funding woes. This 1815 spark ignited a revolution that stitched America together, for better or worse. It showed how one bold idea, chartered on a winter day, could propel a nation forward at breakneck speed. Now, how does this dusty charter benefit you today? In a world of gig economies, AI disruptions, and endless side hustles, Stevens' perseverance offers timeless tracks to success. Here's how to apply it personally: - **Embrace Innovation in Everyday Challenges**: Just as Stevens pivoted from steamboats to rails, scan your routine for upgrades. Bullet point plan: Identify one outdated habit (e.g., manual budgeting), research modern tools (apps like Mint), implement weekly (track expenses Sundays), review monthly for savings – aim for 10% budget cut in three months. - **Persist Through Rejections**: Stevens' 1811 flop didn't stop him; he refined and returned. In your career, treat "no" as "not yet." Plan: After a job rejection, analyze feedback, update resume with one new skill (e.g., learn Python via free Codecademy course, 2 hours/week), network on LinkedIn (connect with 5 pros weekly), reapply to similar roles quarterly – target promotion or raise in six months. - **Build Networks Like Rail Lines**: Railroads connected isolated towns; connect your skills to opportunities. Plan: Map your "network tracks" – list 10 contacts, reach out monthly with value (share articles), join one group (e.g., local Toastmasters), host a virtual coffee chat biweekly – grow to 50 meaningful connections in a year, opening doors to collaborations. - **Calculate Risks with Data**: Stevens' pamphlet crunched numbers; do the same for decisions. Plan: For a side hustle (e.g., freelancing), estimate costs/revenue (spreadsheet: $500 startup, $200/month goal), test small (one client via Upwork), scale if profitable (add marketing after three months) – achieve break-even in quarter one, profit in quarter two. - **Adapt to Changing Landscapes**: Railroads conquered hills; adapt to life's obstacles. Plan: Face a setback (e.g., health issue), research solutions (apps like MyFitnessPal), set milestones (walk 10k steps daily), adjust as needed (switch to yoga if needed), celebrate wins weekly – regain momentum in 30 days. Follow this six-month plan: Months 1-2 focus on innovation and persistence (daily journaling wins), 3-4 on networking and risks (monthly reviews), 5-6 on adaptation (quarterly goals reset). Like Stevens' charter, your small start can lead to massive momentum – chug on!