Part I: The Paradox of January 26

History, in its popular form, is often a curated gallery of conquerors and kings, a simplified timeline where dates serve as mere hooks for the most convenient narratives. We remember 1492; we remember 1776. But the true machinery of human progress is often found in the days that slipped through the cracks—the dates when the world fundamentally shifted, yet the credit was lost to politics, tragedy, or the slow erosion of time. January 26, 1500, is one such day.

On this specific date, a singular event occurred that rewrote the map of the Western Hemisphere and challenged the physics of the known world, yet it remains obscured in the shadow of more famous names like Christopher Columbus and Pedro Álvares Cabral. On January 26, 1500, the Spanish navigator Vicente Yáñez Pinzón—the man who had captained the Niña on Columbus’s first voyage—made landfall on the coast of what is now Brazil. He was likely the first European to set foot on this massive South American landmass, beating the Portuguese claim by nearly three months.

But Pinzón’s discovery was not merely terrestrial. As he navigated the coastline, he encountered a hydrological paradox: a sea that was not salty. He had sailed into the invisible, subterranean force of the Amazon River, a body of fresh water so immense it pushed the Atlantic Ocean back for a hundred miles, creating a "Sweet Sea" (Mar Dulce) in the middle of the hostile, saline ocean.

This report is an exhaustive reconstruction of that voyage. We will dissect the nautical, astronomical, and psychological challenges faced by Pinzón and his crew as they plunged into the "Torrid Zone," a region ancient philosophers claimed was uninhabitable. We will explore the terror of losing the North Star, the discovery of the Southern Cross, and the sensory cognitive dissonance of tasting fresh water while out of sight of land.

However, this is not a dusty archival record. It is a tactical manual. By analyzing the "Mar Dulce" event, we derive a high-performance methodology for the modern individual. We call this the Sweet Sea Protocol. It is a strategy for navigating personal ambiguity, identifying resource-rich anomalies in "saline" environments (hostile markets, difficult life phases, or creative blocks), and executing resilience plans when traditional guidance systems fail.

January 26 is the day the ocean turned sweet. This report details how it happened, and how you can replicate the phenomenon in the geography of your own life.

Part II: The Architects of the Void (Pre-1500 Context)

The Shadow of the Admiral and the Pinzón Dynasty

To understand the magnitude of the feat accomplished on January 26, 1500, one must first dismantle the popular myth of the "lonely genius" Columbus and illuminate the pragmatic competence of the Pinzón family. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was not a novice stumbling upon a continent; he was a scion of a maritime dynasty from Palos de la Frontera, a clan of shipowners and corsairs who were arguably the finest sailors in Castile.

The Pinzóns—brothers Martín Alonso, Vicente Yáñez, and Francisco Martín—were the engine room of the 1492 discovery. While Christopher Columbus possessed the visionary fervor and the courtly connections to secure funding from Isabella and Ferdinand, he lacked the deep, tacit knowledge of the Atlantic currents and the respect of the Andalusian crews. It was the Pinzón brothers who provided the Niña and the Pinta. It was Martín Alonso Pinzón who quelled the mutinies when the crew wanted to throw the "Genoese madman" overboard. And it was Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, captain of the Niña, who brought the Admiral home safely after the flagship Santa María was wrecked on the reefs of Hispaniola. The aftermath of 1492 was bitter. The relationship between Columbus and the Pinzóns disintegrated into a feud over credit and authority. Martín Alonso died shortly after their return in 1493, exhausted and arguably heartbroken by the conflict, leaving Vicente as the head of the family legacy. For seven years, Vicente lived in the shadow of the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea," entangled in the pleitos colombinos (the lawsuits against the Crown regarding Columbus's monopoly).

By 1499, the cracks in Columbus's monopoly had widened. The Crown, realizing the sheer vastness of the ocean and Columbus's administrative failures in Hispaniola, began issuing licenses for "Andalusian Voyages" or "Minor Voyages" to other trusted navigators. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón saw his opening. He did not want to merely ferry supplies to the colonies; he wanted to explore the "Unknown South." He secured a capitulation (license) from the Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca to explore the lands to the south of the known islands.

The Fleet of the Redemption

In November 1499, Pinzón departed from the harbor of Palos. He did not take a massive armada. He took four caravels.

These ships were the spacecraft of the Renaissance—marvels of buoyancy and adaptability, yet terrifyingly small by modern standards. A typical caravel of the era, like the Niña, was perhaps 20 to 25 meters in length, with a shallow draft that allowed it to explore river mouths but made it toss violently in the open swells of the Atlantic.

The specific names of the four ships in the 1499 fleet are not as universally recorded as the trio of 1492, but records suggest they were small, roughly 50-60 tons each, crewed by kinsmen and neighbors from Palos and Huelva. These men were not mercenaries; they were a community. They were sailing into the void with their cousins and brothers, a factor that would become crucial when the psychological pressures of the "Torrid Zone" began to mount.

The provisioning was standard for the time, yet wholly inadequate for the unknown duration of the voyage: hardtack (biscuits) that would inevitably turn to powder or host weevils; salted beef and pork; wine; and water stored in wooden casks that would grow slimy with algae within weeks. The search for fresh water was not just a matter of comfort; it was the primary ticking clock of the expedition.

Part III: The Descent into the Torrid Zone

The Psychological Barrier of the Equator

Pinzón’s route was aggressive. Instead of taking the comfortable trade winds west to the Caribbean, he turned south-southwest. He stopped at the Cape Verde Islands, the last outpost of the known world, and then committed his ships to the open southern Atlantic.

This decision required immense intellectual courage. In 1500, the "Torrid Zone" (the area between the Tropics) was still shrouded in the dread of ancient geography. Aristotle and other classical authorities had theorized that the heat in this zone was so intense it would boil the sea and incinerate human flesh. While Portuguese explorers had crossed the equator along the African coast, sailing into the open equatorial ocean was a different terror. The sun stood directly overhead at noon, casting no shadows. The heat was oppressive, melting the pitch in the deck seams and spoiling the food supplies rapidly.

The Vanishing of the North Star

As the fleet plunged southward, crossing the Equator, they encountered a phenomenon that terrified the 15th-century mariner more than sea monsters: the sky broke.

The aftermath of 1492 was bitter. The relationship between Columbus and the Pinzóns disintegrated into a feud over credit and authority. Martín Alonso died shortly after their return in 1493, exhausted and arguably heartbroken by the conflict, leaving Vicente as the head of the family legacy. For seven years, Vicente lived in the shadow of the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea," entangled in the pleitos colombinos (the lawsuits against the Crown regarding Columbus's monopoly).

By 1499, the cracks in Columbus's monopoly had widened. The Crown, realizing the sheer vastness of the ocean and Columbus's administrative failures in Hispaniola, began issuing licenses for "Andalusian Voyages" or "Minor Voyages" to other trusted navigators. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón saw his opening. He did not want to merely ferry supplies to the colonies; he wanted to explore the "Unknown South." He secured a capitulation (license) from the Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca to explore the lands to the south of the known islands.

The Fleet of the Redemption

In November 1499, Pinzón departed from the harbor of Palos. He did not take a massive armada. He took four caravels.

These ships were the spacecraft of the Renaissance—marvels of buoyancy and adaptability, yet terrifyingly small by modern standards. A typical caravel of the era, like the Niña, was perhaps 20 to 25 meters in length, with a shallow draft that allowed it to explore river mouths but made it toss violently in the open swells of the Atlantic.

The specific names of the four ships in the 1499 fleet are not as universally recorded as the trio of 1492, but records suggest they were small, roughly 50-60 tons each, crewed by kinsmen and neighbors from Palos and Huelva. These men were not mercenaries; they were a community. They were sailing into the void with their cousins and brothers, a factor that would become crucial when the psychological pressures of the "Torrid Zone" began to mount.

The provisioning was standard for the time, yet wholly inadequate for the unknown duration of the voyage: hardtack (biscuits) that would inevitably turn to powder or host weevils; salted beef and pork; wine; and water stored in wooden casks that would grow slimy with algae within weeks. The search for fresh water was not just a matter of comfort; it was the primary ticking clock of the expedition.

Part III: The Descent into the Torrid Zone

The Psychological Barrier of the Equator

Pinzón’s route was aggressive. Instead of taking the comfortable trade winds west to the Caribbean, he turned south-southwest. He stopped at the Cape Verde Islands, the last outpost of the known world, and then committed his ships to the open southern Atlantic.

This decision required immense intellectual courage. In 1500, the "Torrid Zone" (the area between the Tropics) was still shrouded in the dread of ancient geography. Aristotle and other classical authorities had theorized that the heat in this zone was so intense it would boil the sea and incinerate human flesh. While Portuguese explorers had crossed the equator along the African coast, sailing into the open equatorial ocean was a different terror. The sun stood directly overhead at noon, casting no shadows. The heat was oppressive, melting the pitch in the deck seams and spoiling the food supplies rapidly.

The Vanishing of the North Star

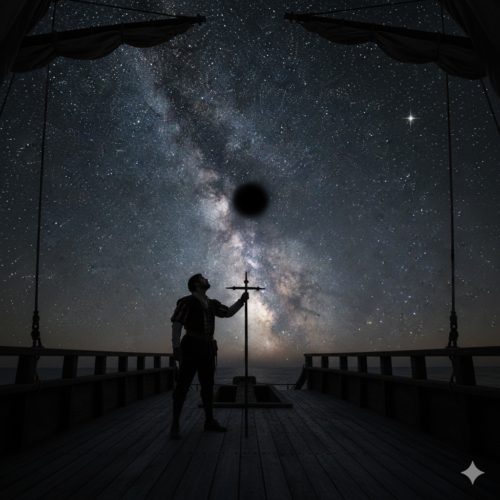

As the fleet plunged southward, crossing the Equator, they encountered a phenomenon that terrified the 15th-century mariner more than sea monsters: the sky broke. For millennia, European navigation relied on Polaris (the North Star). It was the immutable anchor of the night sky, the one point that did not move. It told the sailor where North was, and more importantly, its height above the horizon told them their latitude (how far north they were).

As Pinzón sailed south, Polaris sank lower and lower each night. The "Guards" of the Little Dipper dipped below the waves. Finally, the North Star vanished entirely into the sea behind them.

For the crew, this was an existential crisis. They were sailing off the edge of their star charts. It was akin to a modern pilot losing their GPS, altimeter, and magnetic compass simultaneously in heavy cloud cover. They were "blind" in the vertical sense. They had no way to measure their progress or their position relative to home. The psychological weight of this cannot be overstated—they were drifting in a void where the heavens themselves had become foreign.

The Astronomer of the Abyss

Pinzón, however, did not panic. He possessed a scientific mind that transcended the superstitions of his era. Realizing the old tools were useless, he began to observe the new sky.

He became one of the first Europeans to systematically observe and record the southern constellations. He noted the brilliance of the constellation we now know as Crux (the Southern Cross). But his most remarkable observation was of the darkness, not the light.

Pinzón documented a "black patch" in the Milky Way, a void where no stars shone. He described it as a dark cloud that obscured the heavens. This was the Coalsack Nebula (Caldwell 99), a dark nebula of interstellar dust that silhouettes against the bright band of the galaxy. Indigenous Australians and South Americans had known of it for thousands of years—often seeing it as a giant Emu or a part of their cosmology—but to European science, it was unknown.

Pinzón’s observation of the Coalsack Nebula is a testament to his powers of perception. He was navigating by the absence of light. He used the geometry of the void to orient his ships. This ability to find structure in the darkness is a key component of his legacy, and the first pillar of our "Sweet Sea Protocol."

Part IV: January 26, 1500 — The Cape of Consolation

The Landfall

After weeks of struggling against the equatorial doldrums (the ITCZ) and the strange southern currents, the lookout on the lead caravel sighted land on the morning of January 26, 1500.

It was not the lush, manicured islands of the Caribbean. It was a rugged promontory of dunes and cliffs, battered by the Atlantic surf. Pinzón named it Cabo de Santa María de la Consolación (Cape of Saint Mary of Consolation). The name is telling. He did not name it for victory, or gold, or a monarch. He named it for relief. The discovery was the "consolation" for the terror of the void.

Most modern historians identify this landfall as Cabo de Santo Agostinho, in the present-day state of Pernambuco, Brazil, near Recife. This places Pinzón in Brazil nearly three months before Pedro Álvares Cabral, who is officially credited with the "discovery" by the Portuguese on April 22, 1500.

For millennia, European navigation relied on Polaris (the North Star). It was the immutable anchor of the night sky, the one point that did not move. It told the sailor where North was, and more importantly, its height above the horizon told them their latitude (how far north they were).

As Pinzón sailed south, Polaris sank lower and lower each night. The "Guards" of the Little Dipper dipped below the waves. Finally, the North Star vanished entirely into the sea behind them.

For the crew, this was an existential crisis. They were sailing off the edge of their star charts. It was akin to a modern pilot losing their GPS, altimeter, and magnetic compass simultaneously in heavy cloud cover. They were "blind" in the vertical sense. They had no way to measure their progress or their position relative to home. The psychological weight of this cannot be overstated—they were drifting in a void where the heavens themselves had become foreign.

The Astronomer of the Abyss

Pinzón, however, did not panic. He possessed a scientific mind that transcended the superstitions of his era. Realizing the old tools were useless, he began to observe the new sky.

He became one of the first Europeans to systematically observe and record the southern constellations. He noted the brilliance of the constellation we now know as Crux (the Southern Cross). But his most remarkable observation was of the darkness, not the light.

Pinzón documented a "black patch" in the Milky Way, a void where no stars shone. He described it as a dark cloud that obscured the heavens. This was the Coalsack Nebula (Caldwell 99), a dark nebula of interstellar dust that silhouettes against the bright band of the galaxy. Indigenous Australians and South Americans had known of it for thousands of years—often seeing it as a giant Emu or a part of their cosmology—but to European science, it was unknown.

Pinzón’s observation of the Coalsack Nebula is a testament to his powers of perception. He was navigating by the absence of light. He used the geometry of the void to orient his ships. This ability to find structure in the darkness is a key component of his legacy, and the first pillar of our "Sweet Sea Protocol."

Part IV: January 26, 1500 — The Cape of Consolation

The Landfall

After weeks of struggling against the equatorial doldrums (the ITCZ) and the strange southern currents, the lookout on the lead caravel sighted land on the morning of January 26, 1500.

It was not the lush, manicured islands of the Caribbean. It was a rugged promontory of dunes and cliffs, battered by the Atlantic surf. Pinzón named it Cabo de Santa María de la Consolación (Cape of Saint Mary of Consolation). The name is telling. He did not name it for victory, or gold, or a monarch. He named it for relief. The discovery was the "consolation" for the terror of the void.

Most modern historians identify this landfall as Cabo de Santo Agostinho, in the present-day state of Pernambuco, Brazil, near Recife. This places Pinzón in Brazil nearly three months before Pedro Álvares Cabral, who is officially credited with the "discovery" by the Portuguese on April 22, 1500. The Ritual of Possession

Pinzón and his captains rowed ashore to perform the auto de posesión. The ritual was a bizarre mix of legalism and theatre. The notary of the fleet would have unrolled a parchment, read a declaration claiming the land for the Monarchs of Castile (Ferdinand and Isabella), and the captains would have cut branches from the trees with their swords and drunk water from the local soil.

They carved the names of the ships and the date—January 26, 1500—into the bark of the trees and the faces of the rocks. This was their attempt to impose order on the chaos of the unknown, to brand the wilderness with the bureaucracy of Europe.

The Indigenous Encounter

The encounter with the local inhabitants was not the peaceful trade they had found in the Bahamas in 1492. The indigenous peoples of this coast (likely Tupi or Potiguara speakers) were distinct. They were wary, often hostile to these bearded strangers encasing themselves in metal and arriving on floating fortresses.

Pinzón noted huge footprints in the sand and described the people as large and formidable. Skirmishes occurred. There was no gold to be found on the beaches, only vast forests of dyewood (brazilwood) and strange animals. The crew, expecting the riches of the Orient (since they still believed they might be near the Ganges), were disillusioned. They had found a continent, but it offered them no immediate reward.

Part V: The Mystery of the Sweet Sea

The Anomaly of the Water

Disappointed by the hostility and the lack of gold at the Cape of Consolation, Pinzón ordered the fleet to sail northwest, hugging the coastline. He assumed he was on an island or a peninsula of Asia.

As they sailed north, the environment began to shift in a way that defied their nautical experience. The water, usually a deep, clear oceanic blue in the deep Atlantic, turned turbid and silty. The waves grew choppy, not from wind, but from a collision of massive currents.

Then, the sailors noticed something impossible.

The Ritual of Possession

Pinzón and his captains rowed ashore to perform the auto de posesión. The ritual was a bizarre mix of legalism and theatre. The notary of the fleet would have unrolled a parchment, read a declaration claiming the land for the Monarchs of Castile (Ferdinand and Isabella), and the captains would have cut branches from the trees with their swords and drunk water from the local soil.

They carved the names of the ships and the date—January 26, 1500—into the bark of the trees and the faces of the rocks. This was their attempt to impose order on the chaos of the unknown, to brand the wilderness with the bureaucracy of Europe.

The Indigenous Encounter

The encounter with the local inhabitants was not the peaceful trade they had found in the Bahamas in 1492. The indigenous peoples of this coast (likely Tupi or Potiguara speakers) were distinct. They were wary, often hostile to these bearded strangers encasing themselves in metal and arriving on floating fortresses.

Pinzón noted huge footprints in the sand and described the people as large and formidable. Skirmishes occurred. There was no gold to be found on the beaches, only vast forests of dyewood (brazilwood) and strange animals. The crew, expecting the riches of the Orient (since they still believed they might be near the Ganges), were disillusioned. They had found a continent, but it offered them no immediate reward.

Part V: The Mystery of the Sweet Sea

The Anomaly of the Water

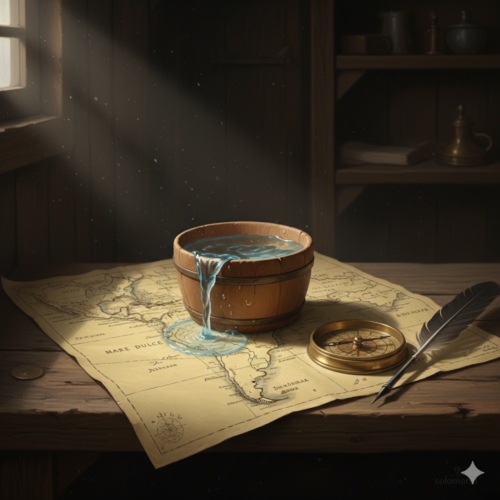

Disappointed by the hostility and the lack of gold at the Cape of Consolation, Pinzón ordered the fleet to sail northwest, hugging the coastline. He assumed he was on an island or a peninsula of Asia.

As they sailed north, the environment began to shift in a way that defied their nautical experience. The water, usually a deep, clear oceanic blue in the deep Atlantic, turned turbid and silty. The waves grew choppy, not from wind, but from a collision of massive currents.

Then, the sailors noticed something impossible. They were sailing well out of sight of land—perhaps 20 to 40 leagues (60 to 120 miles) offshore—yet the spray hitting their faces didn't sting with salt. The water teeming around their hulls was muddy and opaque.

Pinzón ordered a bucket lowered. The crew hauled it up. They tasted it.

It was fresh water.

They were in the open ocean, yet they were drinking sweet, potable water. This cognitive dissonance stunned the fleet. A river had to be nearby, but a river of what magnitude could stain the Atlantic Ocean freshwater for a hundred miles? In Europe, the great rivers—the Tagus, the Guadalquivir, the Rhine—faded into the sea within mere miles.

Pinzón realized they had found something geologically monstrous. He named this body of water Santa María de la Mar Dulce—Saint Mary of the Sweet Sea.

Into the Mouth of the Giant

They turned the prows toward the source of the flow. They entered the mouth of the Amazon River.

Pinzón explored the estuary of the Amazon, likely venturing about 50 miles upstream. He witnessed the pororoca, the thunderous tidal bore where the Atlantic tide crashes against the river's massive output. The roar of the pororoca can be heard thirty minutes before it arrives, a wall of water up to four meters high traveling at 800 kilometers per hour. For a Spanish sailor used to the mild tides of the Mediterranean or the predictable tides of Palos, this would have sounded like the roar of a sea monster.

He saw the vast rainforests (which he called "Marañón") and realized this was not an island. The volume of water suggested a continent of immense size, a landmass large enough to feed a river that could dilute an ocean.

This was the true discovery of the voyage. While he didn't find cities of gold, he found the hydrological heart of South America. He had discovered the largest river system on Earth, not by seeing it on a map, but by tasting the anomaly in the water.

Part VI: The Return and the Erasure

The Hurricane and the Tragedy

The return voyage was a catastrophe that nearly erased the discovery from history. After leaving the Amazon and exploring the Guianas and Venezuela (Gulf of Paria), the fleet turned north toward Hispaniola to rest and refit.

In July 1500, a hurricane struck the fleet in the Bahamas. This was the season of storms that the Taino feared, the juracán. Pinzón’s small caravels were tossed like toys. Two of the four ships were obliterated. They sank with all hands—friends, cousins, and neighbors of Pinzón from Palos.

The remaining two ships, battered and leaking, limped back to Palos, arriving in September 1500. Pinzón returned with a cargo of brazilwood and some indigenous captives, but no gold. He had lost half his men and half his fleet.

The Treaty of Tordesillas: The Erasure of Claims

To make matters worse, the news arrived that the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral had landed in Brazil in April 1500, three months after Pinzón.

Here, the invisible lines of politics crushed the physical reality of discovery. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) had divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal. The line was drawn 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands.

Pinzón’s discovery—the Cape of Consolation and the mouth of the Amazon—fell east of this line. By the stroke of a pen on a map in the Vatican and Tordesillas, the land Pinzón had risked his life to find belonged to the King of Portugal.

Spain could not legally claim the land Pinzón had found without violating the treaty. Thus, Pinzón’s discovery of Brazil was largely stricken from the official Spanish maps or downplayed to avoid diplomatic conflict. He was knighted by King Ferdinand and later made Governor of Puerto Rico , but the glory of discovering Brazil was ceded to Cabral.

He had found the continent, tasted the Sweet Sea, and survived the void, only to have politics erase his claim.

Part VII: The Second-Order Insights

The events of January 26, 1500, offer more than a narrative of exploration; they provide a case study in liminality—the state of being between two worlds. Pinzón was between the age of coastal hopping and open-ocean navigation; between the Ptolemaic maps and the new geography; between the North Star and the Southern Cross.

Insight A: The "Mar Dulce" as a Cognitive Model for Scarcity

The discovery of freshwater in the open ocean is a profound metaphor for hidden abundance in hostile environments. Most people (and organizations) operate on the assumption that the "ocean" (the market, the crisis, the unknown) is uniformly "salty" (undrinkable, hostile, resource-poor). Pinzón proved that if you pay attention to the texture and color of the environment, you can find fresh water where it "shouldn't" be. The Amazon's output is so powerful it creates a micro-environment of abundance miles away from the source.

They were sailing well out of sight of land—perhaps 20 to 40 leagues (60 to 120 miles) offshore—yet the spray hitting their faces didn't sting with salt. The water teeming around their hulls was muddy and opaque.

Pinzón ordered a bucket lowered. The crew hauled it up. They tasted it.

It was fresh water.

They were in the open ocean, yet they were drinking sweet, potable water. This cognitive dissonance stunned the fleet. A river had to be nearby, but a river of what magnitude could stain the Atlantic Ocean freshwater for a hundred miles? In Europe, the great rivers—the Tagus, the Guadalquivir, the Rhine—faded into the sea within mere miles.

Pinzón realized they had found something geologically monstrous. He named this body of water Santa María de la Mar Dulce—Saint Mary of the Sweet Sea.

Into the Mouth of the Giant

They turned the prows toward the source of the flow. They entered the mouth of the Amazon River.

Pinzón explored the estuary of the Amazon, likely venturing about 50 miles upstream. He witnessed the pororoca, the thunderous tidal bore where the Atlantic tide crashes against the river's massive output. The roar of the pororoca can be heard thirty minutes before it arrives, a wall of water up to four meters high traveling at 800 kilometers per hour. For a Spanish sailor used to the mild tides of the Mediterranean or the predictable tides of Palos, this would have sounded like the roar of a sea monster.

He saw the vast rainforests (which he called "Marañón") and realized this was not an island. The volume of water suggested a continent of immense size, a landmass large enough to feed a river that could dilute an ocean.

This was the true discovery of the voyage. While he didn't find cities of gold, he found the hydrological heart of South America. He had discovered the largest river system on Earth, not by seeing it on a map, but by tasting the anomaly in the water.

Part VI: The Return and the Erasure

The Hurricane and the Tragedy

The return voyage was a catastrophe that nearly erased the discovery from history. After leaving the Amazon and exploring the Guianas and Venezuela (Gulf of Paria), the fleet turned north toward Hispaniola to rest and refit.

In July 1500, a hurricane struck the fleet in the Bahamas. This was the season of storms that the Taino feared, the juracán. Pinzón’s small caravels were tossed like toys. Two of the four ships were obliterated. They sank with all hands—friends, cousins, and neighbors of Pinzón from Palos.

The remaining two ships, battered and leaking, limped back to Palos, arriving in September 1500. Pinzón returned with a cargo of brazilwood and some indigenous captives, but no gold. He had lost half his men and half his fleet.

The Treaty of Tordesillas: The Erasure of Claims

To make matters worse, the news arrived that the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral had landed in Brazil in April 1500, three months after Pinzón.

Here, the invisible lines of politics crushed the physical reality of discovery. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) had divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal. The line was drawn 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands.

Pinzón’s discovery—the Cape of Consolation and the mouth of the Amazon—fell east of this line. By the stroke of a pen on a map in the Vatican and Tordesillas, the land Pinzón had risked his life to find belonged to the King of Portugal.

Spain could not legally claim the land Pinzón had found without violating the treaty. Thus, Pinzón’s discovery of Brazil was largely stricken from the official Spanish maps or downplayed to avoid diplomatic conflict. He was knighted by King Ferdinand and later made Governor of Puerto Rico , but the glory of discovering Brazil was ceded to Cabral.

He had found the continent, tasted the Sweet Sea, and survived the void, only to have politics erase his claim.

Part VII: The Second-Order Insights

The events of January 26, 1500, offer more than a narrative of exploration; they provide a case study in liminality—the state of being between two worlds. Pinzón was between the age of coastal hopping and open-ocean navigation; between the Ptolemaic maps and the new geography; between the North Star and the Southern Cross.

Insight A: The "Mar Dulce" as a Cognitive Model for Scarcity

The discovery of freshwater in the open ocean is a profound metaphor for hidden abundance in hostile environments. Most people (and organizations) operate on the assumption that the "ocean" (the market, the crisis, the unknown) is uniformly "salty" (undrinkable, hostile, resource-poor). Pinzón proved that if you pay attention to the texture and color of the environment, you can find fresh water where it "shouldn't" be. The Amazon's output is so powerful it creates a micro-environment of abundance miles away from the source.

Insight B: The Southern Cross Pivot

When Polaris vanished, the crew panicked because their metric for success (the height of the North Star) was gone. Pinzón shifted his metric. He looked for the absence of stars (the Coalsack Nebula) and the geometry of new stars (Crux).

Insight C: The Tragedy of Timing vs. The Triumph of Competence

Pinzón arrived first but lost the legacy to Cabral due to the Treaty of Tordesillas. This highlights the distinction between Performance and Recognition. Pinzón performed the feat, but Cabral fit the political narrative.

Implication: Doing the work is only half the equation. Understanding the "Treaty lines" (the political and social context) determines who keeps the territory. However, Pinzón’s resilience—continuing to explore, becoming Governor, and serving the crown until 1514—shows that a legacy of competence outlasts a moment of fame.

Part VIII: The Mar Dulce Protocol (Motivational Plan)

The Goal: To apply the lessons of January 26, 1500, to revolutionize how you navigate uncertainty and scarcity in your personal and professional life today.

The Concept: You are the Captain of the Niña. The "Old World" (your comfort zone) is behind you. The "North Star" (your old reliable guides) has sunk. You are in the Torrid Zone. Your goal is to find your Mar Dulce—your pocket of fresh water in the bitter ocean. Phase 1: The "Cape of Consolation" (Reframing Survival)

Phase 1: The "Cape of Consolation" (Reframing Survival)

Historical Context: Pinzón named his first landfall "Consolation" because surviving the journey was the first victory. He didn't find gold immediately; he found solid ground.

The Modern Problem: We often judge ourselves for not thriving immediately after a major transition (a layoff, a breakup, a move). We expect gold on the beach instantly. When we don't find it, we feel like failures.

The Strategic Fix: Reframe Survival as the First Success. You must identify your "Consolation" point—the baseline of stability that proves you survived the crossing.

Actionable Plan:

The Consolation Audit: For the next 7 days, do not log your "achievements" (sales, gym PRs, completed projects). Instead, log your "Consolations."

Example: "I navigated a hostile meeting without losing my temper." "I got out of bed despite the depressive episode." "I paid the rent while unemployed."

The Ritual: Physically write these down. Like Pinzón carving the date into the tree, you must externalize the fact that you have landed. This builds the psychological foundation required for the next phase of exploration.

Phase 2: Navigating by the Coalsack (The Strategy of Absence)

Historical Context: When the North Star disappeared, Pinzón didn't just look for other bright stars. He mapped the Coalsack Nebula—the dark void. He used the absence of light to orient himself.

The Modern Problem: You are trying to navigate a new reality (e.g., the AI economy, remote work, single parenthood) using old maps (traditional career ladders, parents' advice). You feel lost because you can't see the "North Star." You are looking for "bright spots" (obvious opportunities) that everyone else is also chasing.

The Strategic Fix: Look for the Dark Nebulas. In a saturated market or a confused life, the opportunity lies in the void—the things others are ignoring, avoiding, or are afraid of.

Actionable Plan:

Identify the Vanished Star: Explicitly name the rule or guide that used to work for you but doesn't anymore. (e.g., "Hard work always equals promotion.") Acknowledge it is gone, below the horizon.

Map the Darkness: Identify one area in your industry or life that everyone else is ignoring because it seems "dark," "hard," or "empty."

Example: Everyone is using AI to write content (the bright star). The "dark patch" is human verification and curation. Navigate toward becoming the expert in the thing the AI can't do.

The New Constellation: Create a new metric. If "Latitude" (Job Title) is gone, navigate by "Longitude" (Skill Acquisition).

Phase 3: The Taste Test (The Mar Dulce Principle)

Historical Context: Pinzón found fresh water 100 miles out to sea because he noticed the water changed color and dared to taste it. He didn't wait for land to find water.

The Modern Problem: We assume that because we are in a "hostile" environment (a bad economy, a toxic workplace, a lonely city), there are no resources for us. We assume the ocean is uniformly salty. We starve because we are waiting for "Land" (the perfect job, the perfect partner) to appear before we drink.

The Strategic Fix: Lower the Bucket in the Open Ocean. Anomalies exist. The "Sweet Sea" is often right beneath you, disguised as turbulence.

Actionable Plan:

The 20-League Test: Identify a situation you have written off as "toxic" or "dead." (e.g., "There are no jobs in my field," or "dating in this city is impossible").

Look for Turbidity: Where is the chaos? The Amazon makes the ocean turbid (muddy/messy) where it delivers fresh water. Look for the messy, chaotic parts of your market or life—that is often where the fresh opportunity is pouring in.

The Bucket Drop: Run a micro-experiment to test the water.

Example: If you think your industry is dead (Salty Ocean), find the one messy, chaotic startup that is hiring (Turbid Water) and send a pitch. Do not wait for the "perfect" listing. Taste the water where you are.

Trust Your Senses: If you find a pocket of "fresh water" (a project that brings you joy, a connection that feels right) in the middle of a bad situation, drink it. Do not question why it is there. Use it to refuel for the journey to the source.

Phase 4: Resilience in the Face of the Treaty (The Legacy Play)

Historical Context: Pinzón lost the legal claim to Brazil to Portugal but kept his reputation as a master navigator. He didn't stop sailing. He explored Honduras, Yucatan, and more.

The Modern Problem: You did the work, but someone else got the credit, the promotion, or the inheritance. You feel bitter and want to quit sailing.

The Strategic Fix: Own Your Competence, Release the Credit. The "Treaty lines" (office politics, family dynamics, market shifts) are often out of your control. But your navigational skill is yours forever. Pinzón was hired for voyage after voyage because he knew the ocean, regardless of who owned the map.

Actionable Plan:

The Skill Audit: List the three skills you used to achieve a recent win, regardless of who got the credit. (e.g., "I organized the data," "I calmed the client," "I spotted the error.")

The Pivot: How can you apply those specific skills to a new "voyage" where the Treaty lines are more favorable to you?

The Long Game: Remember that Cabral "discovered" Brazil, but Pinzón knew the Amazon. Real knowledge is a currency that outlasts fame. Focus on acquiring deep knowledge of your craft. The "Crown" (the market) always returns to those who know how to sail.

Conclusion: You Are the Navigator

January 26 is not just a date on the calendar. It is the anniversary of the day a man stood on the edge of a new world, looked at a starless sky, and found his way. It is the anniversary of the day he tasted the ocean and found it sweet.

You will face moments where the stars go out. You will face oceans that seem bitter and endless. You will face storms that claim your "ships" (your resources, your plans). But if you adopt the Pinzón Mindset—curious, observant, resilient—you will find your Mar Dulce.

The fresh water is there. It is pushing against the tide, waiting for you to lower the bucket.

Action Plan Summary for Today (January 26):

Morning: Acknowledge your "Cape of Consolation." Survival is step one.

Noon: Stop looking for the North Star. Identify your new metrics (The Southern Cross).

Afternoon: Look for the "turbid water"—the mess that hides the miracle. Lower the bucket.

Evening: Sail into the river. Claim your discovery, even if the world isn't ready to map it yet.

January 26. The day the ocean turned sweet. Make today your landfall.

The aftermath of 1492 was bitter. The relationship between Columbus and the Pinzóns disintegrated into a feud over credit and authority. Martín Alonso died shortly after their return in 1493, exhausted and arguably heartbroken by the conflict, leaving Vicente as the head of the family legacy. For seven years, Vicente lived in the shadow of the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea," entangled in the pleitos colombinos (the lawsuits against the Crown regarding Columbus's monopoly). By 1499, the cracks in Columbus's monopoly had widened. The Crown, realizing the sheer vastness of the ocean and Columbus's administrative failures in Hispaniola, began issuing licenses for "Andalusian Voyages" or "Minor Voyages" to other trusted navigators. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón saw his opening. He did not want to merely ferry supplies to the colonies; he wanted to explore the "Unknown South." He secured a capitulation (license) from the Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca to explore the lands to the south of the known islands. The Fleet of the Redemption In November 1499, Pinzón departed from the harbor of Palos. He did not take a massive armada. He took four caravels. These ships were the spacecraft of the Renaissance—marvels of buoyancy and adaptability, yet terrifyingly small by modern standards. A typical caravel of the era, like the Niña, was perhaps 20 to 25 meters in length, with a shallow draft that allowed it to explore river mouths but made it toss violently in the open swells of the Atlantic. The specific names of the four ships in the 1499 fleet are not as universally recorded as the trio of 1492, but records suggest they were small, roughly 50-60 tons each, crewed by kinsmen and neighbors from Palos and Huelva. These men were not mercenaries; they were a community. They were sailing into the void with their cousins and brothers, a factor that would become crucial when the psychological pressures of the "Torrid Zone" began to mount. The provisioning was standard for the time, yet wholly inadequate for the unknown duration of the voyage: hardtack (biscuits) that would inevitably turn to powder or host weevils; salted beef and pork; wine; and water stored in wooden casks that would grow slimy with algae within weeks. The search for fresh water was not just a matter of comfort; it was the primary ticking clock of the expedition. Part III: The Descent into the Torrid Zone The Psychological Barrier of the Equator Pinzón’s route was aggressive. Instead of taking the comfortable trade winds west to the Caribbean, he turned south-southwest. He stopped at the Cape Verde Islands, the last outpost of the known world, and then committed his ships to the open southern Atlantic. This decision required immense intellectual courage. In 1500, the "Torrid Zone" (the area between the Tropics) was still shrouded in the dread of ancient geography. Aristotle and other classical authorities had theorized that the heat in this zone was so intense it would boil the sea and incinerate human flesh. While Portuguese explorers had crossed the equator along the African coast, sailing into the open equatorial ocean was a different terror. The sun stood directly overhead at noon, casting no shadows. The heat was oppressive, melting the pitch in the deck seams and spoiling the food supplies rapidly. The Vanishing of the North Star As the fleet plunged southward, crossing the Equator, they encountered a phenomenon that terrified the 15th-century mariner more than sea monsters: the sky broke.

For millennia, European navigation relied on Polaris (the North Star). It was the immutable anchor of the night sky, the one point that did not move. It told the sailor where North was, and more importantly, its height above the horizon told them their latitude (how far north they were). As Pinzón sailed south, Polaris sank lower and lower each night. The "Guards" of the Little Dipper dipped below the waves. Finally, the North Star vanished entirely into the sea behind them. For the crew, this was an existential crisis. They were sailing off the edge of their star charts. It was akin to a modern pilot losing their GPS, altimeter, and magnetic compass simultaneously in heavy cloud cover. They were "blind" in the vertical sense. They had no way to measure their progress or their position relative to home. The psychological weight of this cannot be overstated—they were drifting in a void where the heavens themselves had become foreign. The Astronomer of the Abyss Pinzón, however, did not panic. He possessed a scientific mind that transcended the superstitions of his era. Realizing the old tools were useless, he began to observe the new sky. He became one of the first Europeans to systematically observe and record the southern constellations. He noted the brilliance of the constellation we now know as Crux (the Southern Cross). But his most remarkable observation was of the darkness, not the light. Pinzón documented a "black patch" in the Milky Way, a void where no stars shone. He described it as a dark cloud that obscured the heavens. This was the Coalsack Nebula (Caldwell 99), a dark nebula of interstellar dust that silhouettes against the bright band of the galaxy. Indigenous Australians and South Americans had known of it for thousands of years—often seeing it as a giant Emu or a part of their cosmology—but to European science, it was unknown. Pinzón’s observation of the Coalsack Nebula is a testament to his powers of perception. He was navigating by the absence of light. He used the geometry of the void to orient his ships. This ability to find structure in the darkness is a key component of his legacy, and the first pillar of our "Sweet Sea Protocol." Part IV: January 26, 1500 — The Cape of Consolation The Landfall After weeks of struggling against the equatorial doldrums (the ITCZ) and the strange southern currents, the lookout on the lead caravel sighted land on the morning of January 26, 1500. It was not the lush, manicured islands of the Caribbean. It was a rugged promontory of dunes and cliffs, battered by the Atlantic surf. Pinzón named it Cabo de Santa María de la Consolación (Cape of Saint Mary of Consolation). The name is telling. He did not name it for victory, or gold, or a monarch. He named it for relief. The discovery was the "consolation" for the terror of the void. Most modern historians identify this landfall as Cabo de Santo Agostinho, in the present-day state of Pernambuco, Brazil, near Recife. This places Pinzón in Brazil nearly three months before Pedro Álvares Cabral, who is officially credited with the "discovery" by the Portuguese on April 22, 1500.

The Ritual of Possession Pinzón and his captains rowed ashore to perform the auto de posesión. The ritual was a bizarre mix of legalism and theatre. The notary of the fleet would have unrolled a parchment, read a declaration claiming the land for the Monarchs of Castile (Ferdinand and Isabella), and the captains would have cut branches from the trees with their swords and drunk water from the local soil. They carved the names of the ships and the date—January 26, 1500—into the bark of the trees and the faces of the rocks. This was their attempt to impose order on the chaos of the unknown, to brand the wilderness with the bureaucracy of Europe. The Indigenous Encounter The encounter with the local inhabitants was not the peaceful trade they had found in the Bahamas in 1492. The indigenous peoples of this coast (likely Tupi or Potiguara speakers) were distinct. They were wary, often hostile to these bearded strangers encasing themselves in metal and arriving on floating fortresses. Pinzón noted huge footprints in the sand and described the people as large and formidable. Skirmishes occurred. There was no gold to be found on the beaches, only vast forests of dyewood (brazilwood) and strange animals. The crew, expecting the riches of the Orient (since they still believed they might be near the Ganges), were disillusioned. They had found a continent, but it offered them no immediate reward. Part V: The Mystery of the Sweet Sea The Anomaly of the Water Disappointed by the hostility and the lack of gold at the Cape of Consolation, Pinzón ordered the fleet to sail northwest, hugging the coastline. He assumed he was on an island or a peninsula of Asia. As they sailed north, the environment began to shift in a way that defied their nautical experience. The water, usually a deep, clear oceanic blue in the deep Atlantic, turned turbid and silty. The waves grew choppy, not from wind, but from a collision of massive currents. Then, the sailors noticed something impossible.

They were sailing well out of sight of land—perhaps 20 to 40 leagues (60 to 120 miles) offshore—yet the spray hitting their faces didn't sting with salt. The water teeming around their hulls was muddy and opaque. Pinzón ordered a bucket lowered. The crew hauled it up. They tasted it. It was fresh water. They were in the open ocean, yet they were drinking sweet, potable water. This cognitive dissonance stunned the fleet. A river had to be nearby, but a river of what magnitude could stain the Atlantic Ocean freshwater for a hundred miles? In Europe, the great rivers—the Tagus, the Guadalquivir, the Rhine—faded into the sea within mere miles. Pinzón realized they had found something geologically monstrous. He named this body of water Santa María de la Mar Dulce—Saint Mary of the Sweet Sea. Into the Mouth of the Giant They turned the prows toward the source of the flow. They entered the mouth of the Amazon River. Pinzón explored the estuary of the Amazon, likely venturing about 50 miles upstream. He witnessed the pororoca, the thunderous tidal bore where the Atlantic tide crashes against the river's massive output. The roar of the pororoca can be heard thirty minutes before it arrives, a wall of water up to four meters high traveling at 800 kilometers per hour. For a Spanish sailor used to the mild tides of the Mediterranean or the predictable tides of Palos, this would have sounded like the roar of a sea monster. He saw the vast rainforests (which he called "Marañón") and realized this was not an island. The volume of water suggested a continent of immense size, a landmass large enough to feed a river that could dilute an ocean. This was the true discovery of the voyage. While he didn't find cities of gold, he found the hydrological heart of South America. He had discovered the largest river system on Earth, not by seeing it on a map, but by tasting the anomaly in the water. Part VI: The Return and the Erasure The Hurricane and the Tragedy The return voyage was a catastrophe that nearly erased the discovery from history. After leaving the Amazon and exploring the Guianas and Venezuela (Gulf of Paria), the fleet turned north toward Hispaniola to rest and refit. In July 1500, a hurricane struck the fleet in the Bahamas. This was the season of storms that the Taino feared, the juracán. Pinzón’s small caravels were tossed like toys. Two of the four ships were obliterated. They sank with all hands—friends, cousins, and neighbors of Pinzón from Palos. The remaining two ships, battered and leaking, limped back to Palos, arriving in September 1500. Pinzón returned with a cargo of brazilwood and some indigenous captives, but no gold. He had lost half his men and half his fleet. The Treaty of Tordesillas: The Erasure of Claims To make matters worse, the news arrived that the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral had landed in Brazil in April 1500, three months after Pinzón. Here, the invisible lines of politics crushed the physical reality of discovery. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) had divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal. The line was drawn 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands. Pinzón’s discovery—the Cape of Consolation and the mouth of the Amazon—fell east of this line. By the stroke of a pen on a map in the Vatican and Tordesillas, the land Pinzón had risked his life to find belonged to the King of Portugal. Spain could not legally claim the land Pinzón had found without violating the treaty. Thus, Pinzón’s discovery of Brazil was largely stricken from the official Spanish maps or downplayed to avoid diplomatic conflict. He was knighted by King Ferdinand and later made Governor of Puerto Rico , but the glory of discovering Brazil was ceded to Cabral. He had found the continent, tasted the Sweet Sea, and survived the void, only to have politics erase his claim. Part VII: The Second-Order Insights The events of January 26, 1500, offer more than a narrative of exploration; they provide a case study in liminality—the state of being between two worlds. Pinzón was between the age of coastal hopping and open-ocean navigation; between the Ptolemaic maps and the new geography; between the North Star and the Southern Cross. Insight A: The "Mar Dulce" as a Cognitive Model for Scarcity The discovery of freshwater in the open ocean is a profound metaphor for hidden abundance in hostile environments. Most people (and organizations) operate on the assumption that the "ocean" (the market, the crisis, the unknown) is uniformly "salty" (undrinkable, hostile, resource-poor). Pinzón proved that if you pay attention to the texture and color of the environment, you can find fresh water where it "shouldn't" be. The Amazon's output is so powerful it creates a micro-environment of abundance miles away from the source.

Phase 1: The "Cape of Consolation" (Reframing Survival)