Imagine a world where a young nation, battered by wars and economic turmoil, claws its way out of crippling debt to stand tall with a clean slate. On January 8, 1835, that's exactly what happened in the United States. President Andrew Jackson, the fiery frontiersman turned commander-in-chief, announced to Congress that the national debt had been paid off in full—the first and only time in American history. This wasn't just a fiscal footnote; it was a monumental achievement that reshaped the young republic's identity, proving that determination, strategic maneuvering, and a bit of economic luck could turn the tide against overwhelming odds. But beyond the dusty pages of history books, this event holds timeless lessons for anyone grappling with personal finances today. In this deep dive, we'll unpack the gritty details of how America got into debt, how Jackson bulldozed his way out of it, and the ripple effects that followed. Then, we'll flip the script to show how you can channel that same grit to transform your own life—one smart decision at a time. Let's start at the beginning, because to appreciate the triumph of 1835, you need to understand the quagmire that preceded it. The United States' national debt didn't spring up overnight; it was born from the fires of revolution. When the Continental Congress declared independence in 1776, they had no treasury, no central bank, and certainly no credit line. To fund the fight against Britain, they printed paper money called Continentals, which quickly became worthless—hence the phrase "not worth a Continental." By war's end in 1783, the fledgling nation owed about $43 million to foreign creditors like France and the Netherlands, plus another $11 million to domestic lenders. That's equivalent to roughly $1.2 billion in today's dollars, but in an era when the entire economy was agrarian and fragile, it felt like an insurmountable mountain.

Enter Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington. In 1790, Hamilton engineered a bold plan to consolidate state debts into a federal one, issuing bonds to fund it. This created the first U.S. national debt of about $75 million. Hamilton saw debt as a tool—a way to build credit, encourage investment, and unify the states. But not everyone agreed. Thomas Jefferson and his allies viewed it as a dangerous yoke, potentially enslaving future generations to bankers and speculators. The debt fluctuated in the early years: it dipped slightly under careful management, but then ballooned again with the Quasi-War against France in the late 1790s and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which added $15 million to the tab.

The real explosion came with the War of 1812. Often called America's "second war of independence," this conflict with Britain was a disaster waiting to happen. The U.S. military was undermanned, the navy was a joke compared to Britain's fleet, and funding was a nightmare. Congress authorized loans, but with European banks tied up in the Napoleonic Wars, interest rates soared to 7-8%. By 1815, when the Treaty of Ghent ended the war, the national debt had skyrocketed to $127 million—nearly double what it was before the fighting started. Cities like Washington, D.C., lay in ruins after British torchings, and the economy was in shambles. Inflation raged, banks failed, and ordinary Americans felt the pinch through higher taxes and worthless currency.

Let's start at the beginning, because to appreciate the triumph of 1835, you need to understand the quagmire that preceded it. The United States' national debt didn't spring up overnight; it was born from the fires of revolution. When the Continental Congress declared independence in 1776, they had no treasury, no central bank, and certainly no credit line. To fund the fight against Britain, they printed paper money called Continentals, which quickly became worthless—hence the phrase "not worth a Continental." By war's end in 1783, the fledgling nation owed about $43 million to foreign creditors like France and the Netherlands, plus another $11 million to domestic lenders. That's equivalent to roughly $1.2 billion in today's dollars, but in an era when the entire economy was agrarian and fragile, it felt like an insurmountable mountain.

Enter Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington. In 1790, Hamilton engineered a bold plan to consolidate state debts into a federal one, issuing bonds to fund it. This created the first U.S. national debt of about $75 million. Hamilton saw debt as a tool—a way to build credit, encourage investment, and unify the states. But not everyone agreed. Thomas Jefferson and his allies viewed it as a dangerous yoke, potentially enslaving future generations to bankers and speculators. The debt fluctuated in the early years: it dipped slightly under careful management, but then ballooned again with the Quasi-War against France in the late 1790s and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which added $15 million to the tab.

The real explosion came with the War of 1812. Often called America's "second war of independence," this conflict with Britain was a disaster waiting to happen. The U.S. military was undermanned, the navy was a joke compared to Britain's fleet, and funding was a nightmare. Congress authorized loans, but with European banks tied up in the Napoleonic Wars, interest rates soared to 7-8%. By 1815, when the Treaty of Ghent ended the war, the national debt had skyrocketed to $127 million—nearly double what it was before the fighting started. Cities like Washington, D.C., lay in ruins after British torchings, and the economy was in shambles. Inflation raged, banks failed, and ordinary Americans felt the pinch through higher taxes and worthless currency. Post-war recovery was slow but steady. Presidents James Madison and James Monroe prioritized debt reduction, using revenues from tariffs on imports and sales of public lands in the West. By 1820, the debt had fallen to about $91 million. The economy began to hum with the advent of the Industrial Revolution—cotton gins, steamboats, and canals boosted trade. Immigration surged, filling the labor force, and the Erie Canal's completion in 1825 opened the Midwest to markets. Still, the debt lingered like a stubborn fog, hovering around $58 million when Andrew Jackson took office in 1829.

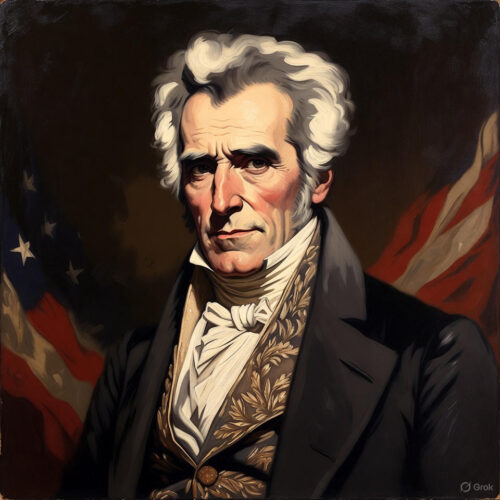

Jackson wasn't your typical politician. Born in 1767 on the Carolina frontier, he was orphaned young, fought in the Revolution as a teenager, and built a reputation as a duelist, lawyer, and military hero. His victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—ironically after the war had ended—made him a national icon. Jackson despised debt on a personal level; he'd lost fortunes in land speculation and banking schemes during the Panic of 1819, which he blamed on corrupt financiers. In his inaugural address, he called the national debt a "national curse" that fostered a "moneyed aristocracy" and vowed to eradicate it. This wasn't just rhetoric—Jackson saw debt elimination as a moral crusade, aligning with his populist vision of a government for the common man, free from elite control.

How did he do it? Jackson's strategy was multifaceted, aggressive, and sometimes ruthless. First, he slashed federal spending. He vetoed more bills than all previous presidents combined, including infrastructure projects like roads and canals that he deemed unconstitutional pork. The Maysville Road veto in 1830, for example, blocked funding for a Kentucky turnpike, arguing it benefited only one state. This frugality extended to the military; Jackson reduced army and navy budgets, relying on militias instead. By cutting waste, he freed up millions.

Post-war recovery was slow but steady. Presidents James Madison and James Monroe prioritized debt reduction, using revenues from tariffs on imports and sales of public lands in the West. By 1820, the debt had fallen to about $91 million. The economy began to hum with the advent of the Industrial Revolution—cotton gins, steamboats, and canals boosted trade. Immigration surged, filling the labor force, and the Erie Canal's completion in 1825 opened the Midwest to markets. Still, the debt lingered like a stubborn fog, hovering around $58 million when Andrew Jackson took office in 1829.

Jackson wasn't your typical politician. Born in 1767 on the Carolina frontier, he was orphaned young, fought in the Revolution as a teenager, and built a reputation as a duelist, lawyer, and military hero. His victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—ironically after the war had ended—made him a national icon. Jackson despised debt on a personal level; he'd lost fortunes in land speculation and banking schemes during the Panic of 1819, which he blamed on corrupt financiers. In his inaugural address, he called the national debt a "national curse" that fostered a "moneyed aristocracy" and vowed to eradicate it. This wasn't just rhetoric—Jackson saw debt elimination as a moral crusade, aligning with his populist vision of a government for the common man, free from elite control.

How did he do it? Jackson's strategy was multifaceted, aggressive, and sometimes ruthless. First, he slashed federal spending. He vetoed more bills than all previous presidents combined, including infrastructure projects like roads and canals that he deemed unconstitutional pork. The Maysville Road veto in 1830, for example, blocked funding for a Kentucky turnpike, arguing it benefited only one state. This frugality extended to the military; Jackson reduced army and navy budgets, relying on militias instead. By cutting waste, he freed up millions. Second, revenues soared thanks to a booming economy. The 1820s and early 1830s were a golden age for American growth. Cotton exports to Europe exploded, fueled by slave labor in the South—though this dark underbelly can't be ignored, as Jackson himself was a slaveowner with plantations. Tariffs, protective taxes on imports, brought in huge sums; the Tariff of 1828 (dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners) alone generated over $20 million annually. Jackson navigated the backlash, compromising with the Tariff of 1832 to avert nullification crises in South Carolina.

Third, and most controversially, Jackson monetized the West. The federal government owned vast public domains—millions of acres seized from Native Americans through treaties and force. Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 accelerated this, displacing tribes like the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears to open lands for sale. Speculators and settlers snapped up parcels at rock-bottom prices, generating $25 million in 1836 alone. This land boom was a double-edged sword: it paid down debt but inflated a speculative bubble.

By 1834, the debt had dwindled to under $5 million. Jackson, ever the showman, timed the final push perfectly. On December 5, 1834, in his annual message to Congress, he predicted the debt would be extinguished by year's end. The last bonds were redeemed, and on January 8, 1835, Jackson delivered a special message confirming the milestone: the United States was debt-free, with a surplus of about $440,000 in the treasury. Celebrations erupted—parades in Washington, toasts across the nation. Newspapers hailed it as a "glorious era," and Jackson's popularity soared. For a brief moment, America stood as a beacon of fiscal responsibility in a world of indebted monarchies.

But history loves irony, and the aftermath was anything but smooth. Without debt, the government had no place to park its surplus. Jackson distributed funds to states via the Deposit Act of 1836, fueling even more speculation. Banks issued wildcat currency, land prices skyrocketed, and when Britain raised interest rates in 1836, the bubble burst. The Panic of 1837 plunged the U.S. into a depression: banks collapsed, unemployment hit 25% in some cities, and the debt crept back up to $3.3 million by 1838 under President Martin Van Buren. Jackson's successor inherited the mess, but the old general retired to his Hermitage plantation, unrepentant.

Digging deeper into the economic mechanics, Jackson's war on the Second Bank of the United States was pivotal. Chartered in 1816, the Bank stabilized currency and held federal deposits, but Jackson saw it as a monster monopoly. In 1832, he vetoed its recharter, calling it a "hydra of corruption." He then withdrew federal funds in 1833, depositing them in state "pet banks." This "Bank War" weakened central control but freed up resources for debt payment. Critics like Henry Clay argued it destabilized the economy, and they were partly right—the lack of regulation contributed to the 1837 crash.

Socially, the debt payoff reflected Jacksonian democracy's highs and lows. It empowered small farmers and workers by reducing taxes, but at the cost of Native dispossession and ignored infrastructure needs. Women, enslaved people, and free Blacks saw no direct benefits; the era's prosperity was built on exclusion. Internationally, it boosted U.S. credit—European lenders marveled at America's solvency, paving the way for future borrowings.

Second, revenues soared thanks to a booming economy. The 1820s and early 1830s were a golden age for American growth. Cotton exports to Europe exploded, fueled by slave labor in the South—though this dark underbelly can't be ignored, as Jackson himself was a slaveowner with plantations. Tariffs, protective taxes on imports, brought in huge sums; the Tariff of 1828 (dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners) alone generated over $20 million annually. Jackson navigated the backlash, compromising with the Tariff of 1832 to avert nullification crises in South Carolina.

Third, and most controversially, Jackson monetized the West. The federal government owned vast public domains—millions of acres seized from Native Americans through treaties and force. Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 accelerated this, displacing tribes like the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears to open lands for sale. Speculators and settlers snapped up parcels at rock-bottom prices, generating $25 million in 1836 alone. This land boom was a double-edged sword: it paid down debt but inflated a speculative bubble.

By 1834, the debt had dwindled to under $5 million. Jackson, ever the showman, timed the final push perfectly. On December 5, 1834, in his annual message to Congress, he predicted the debt would be extinguished by year's end. The last bonds were redeemed, and on January 8, 1835, Jackson delivered a special message confirming the milestone: the United States was debt-free, with a surplus of about $440,000 in the treasury. Celebrations erupted—parades in Washington, toasts across the nation. Newspapers hailed it as a "glorious era," and Jackson's popularity soared. For a brief moment, America stood as a beacon of fiscal responsibility in a world of indebted monarchies.

But history loves irony, and the aftermath was anything but smooth. Without debt, the government had no place to park its surplus. Jackson distributed funds to states via the Deposit Act of 1836, fueling even more speculation. Banks issued wildcat currency, land prices skyrocketed, and when Britain raised interest rates in 1836, the bubble burst. The Panic of 1837 plunged the U.S. into a depression: banks collapsed, unemployment hit 25% in some cities, and the debt crept back up to $3.3 million by 1838 under President Martin Van Buren. Jackson's successor inherited the mess, but the old general retired to his Hermitage plantation, unrepentant.

Digging deeper into the economic mechanics, Jackson's war on the Second Bank of the United States was pivotal. Chartered in 1816, the Bank stabilized currency and held federal deposits, but Jackson saw it as a monster monopoly. In 1832, he vetoed its recharter, calling it a "hydra of corruption." He then withdrew federal funds in 1833, depositing them in state "pet banks." This "Bank War" weakened central control but freed up resources for debt payment. Critics like Henry Clay argued it destabilized the economy, and they were partly right—the lack of regulation contributed to the 1837 crash.

Socially, the debt payoff reflected Jacksonian democracy's highs and lows. It empowered small farmers and workers by reducing taxes, but at the cost of Native dispossession and ignored infrastructure needs. Women, enslaved people, and free Blacks saw no direct benefits; the era's prosperity was built on exclusion. Internationally, it boosted U.S. credit—European lenders marveled at America's solvency, paving the way for future borrowings. The human stories add flavor to the facts. Take Jackson's personal vendetta: in 1835, an assassin named Richard Lawrence tried to shoot him during a funeral procession—the first attempt on a president's life. The pistols misfired, and Jackson beat the man with his cane. Some quipped it was divine intervention for his debt triumph. Or consider the surplus celebrations: states used their windfalls for schools and roads, but much was squandered on failed banks.

Economists today debate the wisdom of zero debt. Modern theory, from Keynes to Friedman, sees moderate debt as a growth tool—funding wars, infrastructure, or recessions. Jackson's approach was pre-Keynesian, rooted in classical economics emphasizing balanced budgets. Yet, the 1835 milestone proved governments could escape debt traps through discipline, though at a price.

Shifting gears, while the historical saga is fascinating, its real power lies in inspiration. Jackson's debt conquest wasn't magic; it was the result of vision, cuts, and revenue maximization. In today's world of credit cards, student loans, and mortgages, you can apply similar principles to achieve personal financial freedom. Imagine wiping your slate clean—not just surviving, but thriving. The benefits? Reduced stress, more choices, and the thrill of self-mastery. Here's how this 19th-century feat translates to your life, with a step-by-step plan to make it happen.

First, the core benefits: Eliminating debt builds resilience, just as it did for early America. Without interest payments siphoning your income, you gain freedom to pursue dreams—starting a business, traveling, or retiring early. It boosts mental health; studies show debt correlates with anxiety and depression. Financial independence fosters confidence, echoing Jackson's populist empowerment. Plus, it's contagious—your success motivates family and friends.

Now, specific bullet points on how to apply this historical lesson individually:

- **Audit Your "National Debt" Like Hamilton Did in 1790**: Start by listing all debts—credit cards, loans, mortgages—with interest rates and minimum payments. This mirrors how the U.S. consolidated state debts. Use apps like Mint or Excel to track; knowledge is power, revealing where leaks occur.

- **Embrace Jackson's Frugality Veto**: Cut non-essential spending ruthlessly. Skip daily lattes (saving $100/month), cancel unused subscriptions ($50/month), and cook at home instead of dining out ($200/month). Redirect these to debt payments, accelerating payoff like Jackson's vetoes freed funds.

- **Boost Revenues Through Side Hustles, Echoing Land Sales**: Just as western lands generated cash, create extra income. Drive for Uber 10 hours/week ($400/month), sell handmade crafts on Etsy, or freelance writing if skilled. Aim for 20% of main income toward debt, turning hobbies into profit.

- **Prioritize High-Interest Debts Like the War of 1812 Loans**: Use the "debt avalanche" method—pay minimums on all, but extra on highest-interest first. This saves thousands in interest, similar to how post-1815 tariffs targeted costly borrowings.

- **Build an Emergency Fund to Avoid New Debt, Preventing 1837-Style Panics**: Save 3-6 months' expenses in a high-yield account. This buffer, like Jackson's brief surplus, protects against job loss or repairs, breaking the borrowing cycle.

- **Negotiate and Refinance, Channeling Tariff Compromises**: Call creditors for lower rates or consolidate loans at better terms. Refinance mortgages if rates drop, slashing payments like Jackson's 1832 tariff tweaks averted crises.

- **Educate Yourself on Financial "Bank Wars"**: Avoid predatory lenders; learn about credit scores, investing basics via books like "The Total Money Makeover" by Dave Ramsey. This empowers you against modern "moneyed aristocracies" like payday loans.

- **Celebrate Milestones for Motivation, Like 1835 Parades**: When you pay off a card, treat yourself modestly—a movie night, not a spree. Track progress visually with a debt thermometer chart, building momentum.

The human stories add flavor to the facts. Take Jackson's personal vendetta: in 1835, an assassin named Richard Lawrence tried to shoot him during a funeral procession—the first attempt on a president's life. The pistols misfired, and Jackson beat the man with his cane. Some quipped it was divine intervention for his debt triumph. Or consider the surplus celebrations: states used their windfalls for schools and roads, but much was squandered on failed banks.

Economists today debate the wisdom of zero debt. Modern theory, from Keynes to Friedman, sees moderate debt as a growth tool—funding wars, infrastructure, or recessions. Jackson's approach was pre-Keynesian, rooted in classical economics emphasizing balanced budgets. Yet, the 1835 milestone proved governments could escape debt traps through discipline, though at a price.

Shifting gears, while the historical saga is fascinating, its real power lies in inspiration. Jackson's debt conquest wasn't magic; it was the result of vision, cuts, and revenue maximization. In today's world of credit cards, student loans, and mortgages, you can apply similar principles to achieve personal financial freedom. Imagine wiping your slate clean—not just surviving, but thriving. The benefits? Reduced stress, more choices, and the thrill of self-mastery. Here's how this 19th-century feat translates to your life, with a step-by-step plan to make it happen.

First, the core benefits: Eliminating debt builds resilience, just as it did for early America. Without interest payments siphoning your income, you gain freedom to pursue dreams—starting a business, traveling, or retiring early. It boosts mental health; studies show debt correlates with anxiety and depression. Financial independence fosters confidence, echoing Jackson's populist empowerment. Plus, it's contagious—your success motivates family and friends.

Now, specific bullet points on how to apply this historical lesson individually:

- **Audit Your "National Debt" Like Hamilton Did in 1790**: Start by listing all debts—credit cards, loans, mortgages—with interest rates and minimum payments. This mirrors how the U.S. consolidated state debts. Use apps like Mint or Excel to track; knowledge is power, revealing where leaks occur.

- **Embrace Jackson's Frugality Veto**: Cut non-essential spending ruthlessly. Skip daily lattes (saving $100/month), cancel unused subscriptions ($50/month), and cook at home instead of dining out ($200/month). Redirect these to debt payments, accelerating payoff like Jackson's vetoes freed funds.

- **Boost Revenues Through Side Hustles, Echoing Land Sales**: Just as western lands generated cash, create extra income. Drive for Uber 10 hours/week ($400/month), sell handmade crafts on Etsy, or freelance writing if skilled. Aim for 20% of main income toward debt, turning hobbies into profit.

- **Prioritize High-Interest Debts Like the War of 1812 Loans**: Use the "debt avalanche" method—pay minimums on all, but extra on highest-interest first. This saves thousands in interest, similar to how post-1815 tariffs targeted costly borrowings.

- **Build an Emergency Fund to Avoid New Debt, Preventing 1837-Style Panics**: Save 3-6 months' expenses in a high-yield account. This buffer, like Jackson's brief surplus, protects against job loss or repairs, breaking the borrowing cycle.

- **Negotiate and Refinance, Channeling Tariff Compromises**: Call creditors for lower rates or consolidate loans at better terms. Refinance mortgages if rates drop, slashing payments like Jackson's 1832 tariff tweaks averted crises.

- **Educate Yourself on Financial "Bank Wars"**: Avoid predatory lenders; learn about credit scores, investing basics via books like "The Total Money Makeover" by Dave Ramsey. This empowers you against modern "moneyed aristocracies" like payday loans.

- **Celebrate Milestones for Motivation, Like 1835 Parades**: When you pay off a card, treat yourself modestly—a movie night, not a spree. Track progress visually with a debt thermometer chart, building momentum. Finally, a detailed 12-month plan to conquer your debt, inspired by Jackson's six-year push:

Finally, a detailed 12-month plan to conquer your debt, inspired by Jackson's six-year push:

**Month 1: Assessment and Mindset Shift** – Calculate total debt and net worth. Read Jackson's biography snippets for inspiration. Commit to a "no new debt" vow.

**Months 2-3: Budget Boot Camp** – Track every expense for 30 days. Create a zero-based budget where income minus outflows equals zero, allocating extras to debt. Cut 20% of discretionary spending.

**Months 4-6: Income Acceleration** – Launch one side gig. Aim to add $500/month. Apply all to high-interest debt. Review progress quarterly, adjusting as needed.

**Months 7-9: Avalanche Attack** – Focus on top two debts. Automate payments to avoid misses. Build a $1,000 emergency fund if none exists.

**Months 10-12: Surplus Building and Long-Term Vision** – With debts shrinking, start a small investment account (e.g., Roth IRA). Plan post-debt goals—like a vacation fund. If debt-free, redirect payments to savings.

**Ongoing: Annual Review** – Like Jackson's messages to Congress, reassess yearly. Celebrate anniversaries of payoffs to stay motivated.

This isn't easy—Jackson faced assassinations, riots, and recessions—but the payoff is liberation. Just as America emerged stronger (albeit briefly), you'll gain control, opening doors to abundance. History isn't just facts; it's a blueprint for victory. Channel Old Hickory's tenacity, and watch your own "national curse" vanish. Your future self will thank you.

Let's start at the beginning, because to appreciate the triumph of 1835, you need to understand the quagmire that preceded it. The United States' national debt didn't spring up overnight; it was born from the fires of revolution. When the Continental Congress declared independence in 1776, they had no treasury, no central bank, and certainly no credit line. To fund the fight against Britain, they printed paper money called Continentals, which quickly became worthless—hence the phrase "not worth a Continental." By war's end in 1783, the fledgling nation owed about $43 million to foreign creditors like France and the Netherlands, plus another $11 million to domestic lenders. That's equivalent to roughly $1.2 billion in today's dollars, but in an era when the entire economy was agrarian and fragile, it felt like an insurmountable mountain. Enter Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington. In 1790, Hamilton engineered a bold plan to consolidate state debts into a federal one, issuing bonds to fund it. This created the first U.S. national debt of about $75 million. Hamilton saw debt as a tool—a way to build credit, encourage investment, and unify the states. But not everyone agreed. Thomas Jefferson and his allies viewed it as a dangerous yoke, potentially enslaving future generations to bankers and speculators. The debt fluctuated in the early years: it dipped slightly under careful management, but then ballooned again with the Quasi-War against France in the late 1790s and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which added $15 million to the tab. The real explosion came with the War of 1812. Often called America's "second war of independence," this conflict with Britain was a disaster waiting to happen. The U.S. military was undermanned, the navy was a joke compared to Britain's fleet, and funding was a nightmare. Congress authorized loans, but with European banks tied up in the Napoleonic Wars, interest rates soared to 7-8%. By 1815, when the Treaty of Ghent ended the war, the national debt had skyrocketed to $127 million—nearly double what it was before the fighting started. Cities like Washington, D.C., lay in ruins after British torchings, and the economy was in shambles. Inflation raged, banks failed, and ordinary Americans felt the pinch through higher taxes and worthless currency.

Post-war recovery was slow but steady. Presidents James Madison and James Monroe prioritized debt reduction, using revenues from tariffs on imports and sales of public lands in the West. By 1820, the debt had fallen to about $91 million. The economy began to hum with the advent of the Industrial Revolution—cotton gins, steamboats, and canals boosted trade. Immigration surged, filling the labor force, and the Erie Canal's completion in 1825 opened the Midwest to markets. Still, the debt lingered like a stubborn fog, hovering around $58 million when Andrew Jackson took office in 1829. Jackson wasn't your typical politician. Born in 1767 on the Carolina frontier, he was orphaned young, fought in the Revolution as a teenager, and built a reputation as a duelist, lawyer, and military hero. His victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—ironically after the war had ended—made him a national icon. Jackson despised debt on a personal level; he'd lost fortunes in land speculation and banking schemes during the Panic of 1819, which he blamed on corrupt financiers. In his inaugural address, he called the national debt a "national curse" that fostered a "moneyed aristocracy" and vowed to eradicate it. This wasn't just rhetoric—Jackson saw debt elimination as a moral crusade, aligning with his populist vision of a government for the common man, free from elite control. How did he do it? Jackson's strategy was multifaceted, aggressive, and sometimes ruthless. First, he slashed federal spending. He vetoed more bills than all previous presidents combined, including infrastructure projects like roads and canals that he deemed unconstitutional pork. The Maysville Road veto in 1830, for example, blocked funding for a Kentucky turnpike, arguing it benefited only one state. This frugality extended to the military; Jackson reduced army and navy budgets, relying on militias instead. By cutting waste, he freed up millions.

Second, revenues soared thanks to a booming economy. The 1820s and early 1830s were a golden age for American growth. Cotton exports to Europe exploded, fueled by slave labor in the South—though this dark underbelly can't be ignored, as Jackson himself was a slaveowner with plantations. Tariffs, protective taxes on imports, brought in huge sums; the Tariff of 1828 (dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners) alone generated over $20 million annually. Jackson navigated the backlash, compromising with the Tariff of 1832 to avert nullification crises in South Carolina. Third, and most controversially, Jackson monetized the West. The federal government owned vast public domains—millions of acres seized from Native Americans through treaties and force. Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 accelerated this, displacing tribes like the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears to open lands for sale. Speculators and settlers snapped up parcels at rock-bottom prices, generating $25 million in 1836 alone. This land boom was a double-edged sword: it paid down debt but inflated a speculative bubble. By 1834, the debt had dwindled to under $5 million. Jackson, ever the showman, timed the final push perfectly. On December 5, 1834, in his annual message to Congress, he predicted the debt would be extinguished by year's end. The last bonds were redeemed, and on January 8, 1835, Jackson delivered a special message confirming the milestone: the United States was debt-free, with a surplus of about $440,000 in the treasury. Celebrations erupted—parades in Washington, toasts across the nation. Newspapers hailed it as a "glorious era," and Jackson's popularity soared. For a brief moment, America stood as a beacon of fiscal responsibility in a world of indebted monarchies. But history loves irony, and the aftermath was anything but smooth. Without debt, the government had no place to park its surplus. Jackson distributed funds to states via the Deposit Act of 1836, fueling even more speculation. Banks issued wildcat currency, land prices skyrocketed, and when Britain raised interest rates in 1836, the bubble burst. The Panic of 1837 plunged the U.S. into a depression: banks collapsed, unemployment hit 25% in some cities, and the debt crept back up to $3.3 million by 1838 under President Martin Van Buren. Jackson's successor inherited the mess, but the old general retired to his Hermitage plantation, unrepentant. Digging deeper into the economic mechanics, Jackson's war on the Second Bank of the United States was pivotal. Chartered in 1816, the Bank stabilized currency and held federal deposits, but Jackson saw it as a monster monopoly. In 1832, he vetoed its recharter, calling it a "hydra of corruption." He then withdrew federal funds in 1833, depositing them in state "pet banks." This "Bank War" weakened central control but freed up resources for debt payment. Critics like Henry Clay argued it destabilized the economy, and they were partly right—the lack of regulation contributed to the 1837 crash. Socially, the debt payoff reflected Jacksonian democracy's highs and lows. It empowered small farmers and workers by reducing taxes, but at the cost of Native dispossession and ignored infrastructure needs. Women, enslaved people, and free Blacks saw no direct benefits; the era's prosperity was built on exclusion. Internationally, it boosted U.S. credit—European lenders marveled at America's solvency, paving the way for future borrowings.

The human stories add flavor to the facts. Take Jackson's personal vendetta: in 1835, an assassin named Richard Lawrence tried to shoot him during a funeral procession—the first attempt on a president's life. The pistols misfired, and Jackson beat the man with his cane. Some quipped it was divine intervention for his debt triumph. Or consider the surplus celebrations: states used their windfalls for schools and roads, but much was squandered on failed banks. Economists today debate the wisdom of zero debt. Modern theory, from Keynes to Friedman, sees moderate debt as a growth tool—funding wars, infrastructure, or recessions. Jackson's approach was pre-Keynesian, rooted in classical economics emphasizing balanced budgets. Yet, the 1835 milestone proved governments could escape debt traps through discipline, though at a price. Shifting gears, while the historical saga is fascinating, its real power lies in inspiration. Jackson's debt conquest wasn't magic; it was the result of vision, cuts, and revenue maximization. In today's world of credit cards, student loans, and mortgages, you can apply similar principles to achieve personal financial freedom. Imagine wiping your slate clean—not just surviving, but thriving. The benefits? Reduced stress, more choices, and the thrill of self-mastery. Here's how this 19th-century feat translates to your life, with a step-by-step plan to make it happen. First, the core benefits: Eliminating debt builds resilience, just as it did for early America. Without interest payments siphoning your income, you gain freedom to pursue dreams—starting a business, traveling, or retiring early. It boosts mental health; studies show debt correlates with anxiety and depression. Financial independence fosters confidence, echoing Jackson's populist empowerment. Plus, it's contagious—your success motivates family and friends. Now, specific bullet points on how to apply this historical lesson individually: - **Audit Your "National Debt" Like Hamilton Did in 1790**: Start by listing all debts—credit cards, loans, mortgages—with interest rates and minimum payments. This mirrors how the U.S. consolidated state debts. Use apps like Mint or Excel to track; knowledge is power, revealing where leaks occur. - **Embrace Jackson's Frugality Veto**: Cut non-essential spending ruthlessly. Skip daily lattes (saving $100/month), cancel unused subscriptions ($50/month), and cook at home instead of dining out ($200/month). Redirect these to debt payments, accelerating payoff like Jackson's vetoes freed funds. - **Boost Revenues Through Side Hustles, Echoing Land Sales**: Just as western lands generated cash, create extra income. Drive for Uber 10 hours/week ($400/month), sell handmade crafts on Etsy, or freelance writing if skilled. Aim for 20% of main income toward debt, turning hobbies into profit. - **Prioritize High-Interest Debts Like the War of 1812 Loans**: Use the "debt avalanche" method—pay minimums on all, but extra on highest-interest first. This saves thousands in interest, similar to how post-1815 tariffs targeted costly borrowings. - **Build an Emergency Fund to Avoid New Debt, Preventing 1837-Style Panics**: Save 3-6 months' expenses in a high-yield account. This buffer, like Jackson's brief surplus, protects against job loss or repairs, breaking the borrowing cycle. - **Negotiate and Refinance, Channeling Tariff Compromises**: Call creditors for lower rates or consolidate loans at better terms. Refinance mortgages if rates drop, slashing payments like Jackson's 1832 tariff tweaks averted crises. - **Educate Yourself on Financial "Bank Wars"**: Avoid predatory lenders; learn about credit scores, investing basics via books like "The Total Money Makeover" by Dave Ramsey. This empowers you against modern "moneyed aristocracies" like payday loans. - **Celebrate Milestones for Motivation, Like 1835 Parades**: When you pay off a card, treat yourself modestly—a movie night, not a spree. Track progress visually with a debt thermometer chart, building momentum.

Finally, a detailed 12-month plan to conquer your debt, inspired by Jackson's six-year push: