Imagine a bitter winter day in the mid-16th century, where the winds whipping across the English Channel carried not just salt and spray, but the echoes of cannon fire and the clash of steel. On January 7, 1558, the ancient walls of Calais, a stubborn English outpost on French soil for over two centuries, finally crumbled under a relentless French assault. This wasn't just any skirmish; it marked the dramatic end of England's last territorial hold on the European mainland, a pivotal moment that reshaped alliances, humbled a queen, and signaled the close of an era born from the Hundred Years' War. But why does this dusty page from history matter in our fast-paced world of smartphones and deadlines? Because buried in the snow-swept siege lies a blueprint for personal victory—lessons in strategy, resilience, and bold action that can help anyone turn setbacks into comebacks. Dive in with me as we unearth the gripping tale of the Siege of Calais, packed with intrigue, heroism, and a dash of royal heartbreak, before we pivot to how you can channel this epic into your everyday wins.

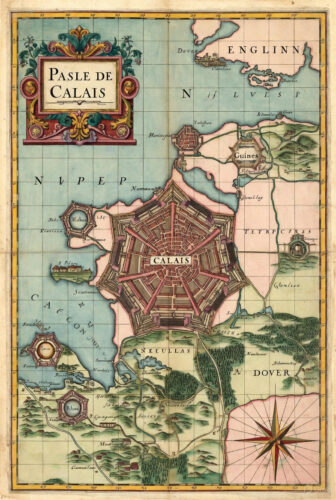

Let's set the stage properly, because this story doesn't start with the first cannonball. The roots dig deep into the muddy battlefields of the Hundred Years' War, which raged from 1337 to 1453 between England and France. Calais fell to English hands in 1347 during a grueling 11-month siege under King Edward III. It was a prize worth the wait: strategically perched on the northern French coast, just 21 miles from Dover, Calais served as a vital gateway for English trade, wool exports, and military incursions into France. For generations, it was the jewel in England's continental crown, a bustling port town where English merchants thrived amid French surroundings. The "Pale of Calais," as the enclave was known, encompassed not just the city but surrounding marshes, forts, and villages, forming a self-contained English territory complete with its own governance and defenses. By the 1550s, however, the world had shifted. England was under the rule of Queen Mary I, a devout Catholic whose marriage to Philip II of Spain in 1554 tied her realm to the sprawling Habsburg empire. This union wasn't just romantic; it was geopolitical dynamite. Spain and France were locked in the Italian Wars, a series of conflicts over control of Italian states that had simmered since 1494. When France, under King Henry II, invaded Spanish territories in Italy in 1557 at the urging of Pope Paul IV, England was dragged in on Spain's side. Mary's government declared war on France in June 1557, committing troops to support Philip's campaigns. This was a risky move for a nation already strained by religious turmoil—the Protestant Reformation was tearing at England's seams—and economic woes.

The catalyst for the siege was the disastrous Battle of St. Quentin in August 1557. There, Spanish forces crushed the French army, capturing key leaders like Constable Anne de Montmorency and leaving the road to Paris vulnerable. Henry II, desperate to regroup, recalled his top commander, Francis, Duke of Guise, from Italy. Guise, a battle-hardened noble from the powerful House of Lorraine, was promoted to lieutenant-general of France. With the French heartland exposed, Henry couldn't afford an open invasion route, but he saw an opportunity in England's distraction. Calais, long a thorn in France's side, became the target. It wasn't just about revenge; reclaiming Calais would boost French morale, secure the northern border, and humiliate England, potentially forcing them out of the war.

Guise's plan was masterful in its secrecy and timing. Winter sieges were rare in the 16th century—harsh weather bogged down armies, froze supplies, and sapped morale. But Guise bet on surprise. In late December 1557, he assembled an army of about 27,000 men—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—at key points like Compiègne, Montreuil-sur-Mer, and Boulogne-sur-Mer. The force included Swiss mercenaries, known for their pike formations, and seasoned French troops fresh from Italian campaigns. Artillery was crucial: Guise brought heavy cannons capable of breaching medieval walls, a nod to the evolving gunpowder warfare that was revolutionizing sieges.

On the English side, Calais was governed by Thomas Wentworth, 2nd Baron Wentworth, a capable but under-resourced administrator. The garrison numbered around 2,500 men, a mix of professional soldiers, local militia, and mercenaries. Defenses were formidable on paper: the city was ringed by thick stone walls, bastions, and a moat fed by the sea. Outlying forts like Risban (guarding the harbor) and Nieullay (protecting the western approaches) formed a layered defense. But years of neglect had taken a toll. Funds from London were sporadic, walls were crumbling in places, and the marshy terrain, while a natural barrier, could turn treacherous in winter floods. Wentworth had warned Queen Mary of vulnerabilities, but reinforcements were slow amid England's internal strife.

By the 1550s, however, the world had shifted. England was under the rule of Queen Mary I, a devout Catholic whose marriage to Philip II of Spain in 1554 tied her realm to the sprawling Habsburg empire. This union wasn't just romantic; it was geopolitical dynamite. Spain and France were locked in the Italian Wars, a series of conflicts over control of Italian states that had simmered since 1494. When France, under King Henry II, invaded Spanish territories in Italy in 1557 at the urging of Pope Paul IV, England was dragged in on Spain's side. Mary's government declared war on France in June 1557, committing troops to support Philip's campaigns. This was a risky move for a nation already strained by religious turmoil—the Protestant Reformation was tearing at England's seams—and economic woes.

The catalyst for the siege was the disastrous Battle of St. Quentin in August 1557. There, Spanish forces crushed the French army, capturing key leaders like Constable Anne de Montmorency and leaving the road to Paris vulnerable. Henry II, desperate to regroup, recalled his top commander, Francis, Duke of Guise, from Italy. Guise, a battle-hardened noble from the powerful House of Lorraine, was promoted to lieutenant-general of France. With the French heartland exposed, Henry couldn't afford an open invasion route, but he saw an opportunity in England's distraction. Calais, long a thorn in France's side, became the target. It wasn't just about revenge; reclaiming Calais would boost French morale, secure the northern border, and humiliate England, potentially forcing them out of the war.

Guise's plan was masterful in its secrecy and timing. Winter sieges were rare in the 16th century—harsh weather bogged down armies, froze supplies, and sapped morale. But Guise bet on surprise. In late December 1557, he assembled an army of about 27,000 men—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—at key points like Compiègne, Montreuil-sur-Mer, and Boulogne-sur-Mer. The force included Swiss mercenaries, known for their pike formations, and seasoned French troops fresh from Italian campaigns. Artillery was crucial: Guise brought heavy cannons capable of breaching medieval walls, a nod to the evolving gunpowder warfare that was revolutionizing sieges.

On the English side, Calais was governed by Thomas Wentworth, 2nd Baron Wentworth, a capable but under-resourced administrator. The garrison numbered around 2,500 men, a mix of professional soldiers, local militia, and mercenaries. Defenses were formidable on paper: the city was ringed by thick stone walls, bastions, and a moat fed by the sea. Outlying forts like Risban (guarding the harbor) and Nieullay (protecting the western approaches) formed a layered defense. But years of neglect had taken a toll. Funds from London were sporadic, walls were crumbling in places, and the marshy terrain, while a natural barrier, could turn treacherous in winter floods. Wentworth had warned Queen Mary of vulnerabilities, but reinforcements were slow amid England's internal strife. The assault began on New Year's Day, January 1, 1558. Guise's vanguard, under his brother Claude, Duke of Aumale, swept in from the south and west, investing the villages of Sangatte, Fréthun, and Nielles-lès-Calais. These moves cut off English supply lines and isolated the outposts. The French artillery, dragged through frozen mud, targeted Fort Risban first. This squat, round tower controlled the harbor entrance, preventing English ships from resupplying the city. By January 2, bombardment had begun in earnest. Cannonballs smashed into the fort's walls, while French infantry stormed the breaches under cover of arquebus fire. The defenders, led by a small contingent, fought fiercely but were overwhelmed. Risban fell that day, its garrison slaughtered or captured.

With the harbor secured, Guise turned to Fort Nieullay (also called Risbank) on January 3. This fort, built on a sandy spit, was crucial for controlling the sluices that flooded the marshes around Calais, a defensive tactic to drown attackers. French engineers, experts in siegecraft from years in Italy, positioned batteries close and pounded the structure. Explosions of gunpowder mines undermined the walls, and by evening, Nieullay too was in French hands. Now, the path to Calais proper was open. Guise's main force encircled the city, digging trenches and erecting earthworks despite the freezing conditions. Sappers tunneled under the walls, placing charges to create breaches.

Inside Calais, panic set in. Wentworth rallied his men, repairing defenses and manning the ramparts. Archers and gunners fired back, but French artillery superiority told. On January 4 and 5, heavy barrages targeted the city's gates and towers. The Castle Gate, a key entry point, was reduced to rubble. French assaults probed the walls, with ladders and scaling parties braving English crossbow bolts and boiling oil. The weather played a role: a sudden thaw turned the ground to slush, hindering movement but also flooding low-lying areas, which Guise used to his advantage by channeling water to isolate sections of the defense.

By January 6, the situation was dire. Breaches gaped in multiple walls, and English ammunition was running low. Wentworth sent desperate pleas for aid to England, but the Channel storms delayed any relief fleet. That night, Guise ordered a general assault. French troops, shouting battle cries, surged forward under cover of darkness. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued on the ramparts—pikes clashing with halberds, swords ringing against armor. The English held some positions, but exhaustion and numbers favored the attackers.

The assault began on New Year's Day, January 1, 1558. Guise's vanguard, under his brother Claude, Duke of Aumale, swept in from the south and west, investing the villages of Sangatte, Fréthun, and Nielles-lès-Calais. These moves cut off English supply lines and isolated the outposts. The French artillery, dragged through frozen mud, targeted Fort Risban first. This squat, round tower controlled the harbor entrance, preventing English ships from resupplying the city. By January 2, bombardment had begun in earnest. Cannonballs smashed into the fort's walls, while French infantry stormed the breaches under cover of arquebus fire. The defenders, led by a small contingent, fought fiercely but were overwhelmed. Risban fell that day, its garrison slaughtered or captured.

With the harbor secured, Guise turned to Fort Nieullay (also called Risbank) on January 3. This fort, built on a sandy spit, was crucial for controlling the sluices that flooded the marshes around Calais, a defensive tactic to drown attackers. French engineers, experts in siegecraft from years in Italy, positioned batteries close and pounded the structure. Explosions of gunpowder mines undermined the walls, and by evening, Nieullay too was in French hands. Now, the path to Calais proper was open. Guise's main force encircled the city, digging trenches and erecting earthworks despite the freezing conditions. Sappers tunneled under the walls, placing charges to create breaches.

Inside Calais, panic set in. Wentworth rallied his men, repairing defenses and manning the ramparts. Archers and gunners fired back, but French artillery superiority told. On January 4 and 5, heavy barrages targeted the city's gates and towers. The Castle Gate, a key entry point, was reduced to rubble. French assaults probed the walls, with ladders and scaling parties braving English crossbow bolts and boiling oil. The weather played a role: a sudden thaw turned the ground to slush, hindering movement but also flooding low-lying areas, which Guise used to his advantage by channeling water to isolate sections of the defense.

By January 6, the situation was dire. Breaches gaped in multiple walls, and English ammunition was running low. Wentworth sent desperate pleas for aid to England, but the Channel storms delayed any relief fleet. That night, Guise ordered a general assault. French troops, shouting battle cries, surged forward under cover of darkness. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued on the ramparts—pikes clashing with halberds, swords ringing against armor. The English held some positions, but exhaustion and numbers favored the attackers. Dawn on January 7 revealed the inevitable. With French forces inside the outer defenses and no hope of reinforcement, Wentworth sued for terms. Guise, ever the chivalrous commander, granted honorable surrender: no massacre, safe passage for civilians and soldiers back to England. Wentworth handed over the keys of the city that afternoon, marking the formal capitulation. The French entered Calais triumphantly, discovering vast stores—food for three months, nearly 300 cannons, and stockpiles of arms. Booty was immense, including tapestries, silver, and wine cellars that reportedly kept the victors merry for days.

The fall didn't stop there. Nearby English-held castles at Guînes and Hammes fell within weeks. Guise pressed on, but Henry II recalled him to counter Spanish threats elsewhere. On January 23, the French king made a grand entry into Calais, declaring it "reclaimed land" and ordering reconstructions. Borders were redrawn, parishes reorganized, and villages rebuilt, integrating the area fully into France.

The shockwaves rippled across Europe. In England, the loss was a national trauma. Queen Mary, already ill, is said to have lamented on her deathbed that "when I am dead and opened, you shall find 'Philip' and 'Calais' lying in my heart." It fueled anti-Spanish sentiment, as many blamed Philip for dragging England into a war that cost them dearly. Economically, the wool trade suffered, shifting focus to Antwerp. Militarily, it forced England to rethink defenses, emphasizing naval power over continental footholds—a pivot that foreshadowed the Elizabethan era's maritime dominance.

For France, it was a morale booster amid defeats. Guise emerged a hero, his lightning campaign studied in military academies for centuries. The siege highlighted gunpowder's role in ending medieval fortifications, accelerating fortress designs like the trace italienne. Politically, it hastened the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, ending the Italian Wars. England nominally retained rights to Calais, but France's payment of 500,000 gold crowns never fully materialized. Elizabeth I, Mary's successor, briefly reasserted claims in 1562 by occupying Le Havre, but French forces expelled them in 1563. The Treaty of Troyes in 1564 sealed French ownership for 120,000 crowns, closing the chapter.

Dawn on January 7 revealed the inevitable. With French forces inside the outer defenses and no hope of reinforcement, Wentworth sued for terms. Guise, ever the chivalrous commander, granted honorable surrender: no massacre, safe passage for civilians and soldiers back to England. Wentworth handed over the keys of the city that afternoon, marking the formal capitulation. The French entered Calais triumphantly, discovering vast stores—food for three months, nearly 300 cannons, and stockpiles of arms. Booty was immense, including tapestries, silver, and wine cellars that reportedly kept the victors merry for days.

The fall didn't stop there. Nearby English-held castles at Guînes and Hammes fell within weeks. Guise pressed on, but Henry II recalled him to counter Spanish threats elsewhere. On January 23, the French king made a grand entry into Calais, declaring it "reclaimed land" and ordering reconstructions. Borders were redrawn, parishes reorganized, and villages rebuilt, integrating the area fully into France.

The shockwaves rippled across Europe. In England, the loss was a national trauma. Queen Mary, already ill, is said to have lamented on her deathbed that "when I am dead and opened, you shall find 'Philip' and 'Calais' lying in my heart." It fueled anti-Spanish sentiment, as many blamed Philip for dragging England into a war that cost them dearly. Economically, the wool trade suffered, shifting focus to Antwerp. Militarily, it forced England to rethink defenses, emphasizing naval power over continental footholds—a pivot that foreshadowed the Elizabethan era's maritime dominance.

For France, it was a morale booster amid defeats. Guise emerged a hero, his lightning campaign studied in military academies for centuries. The siege highlighted gunpowder's role in ending medieval fortifications, accelerating fortress designs like the trace italienne. Politically, it hastened the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, ending the Italian Wars. England nominally retained rights to Calais, but France's payment of 500,000 gold crowns never fully materialized. Elizabeth I, Mary's successor, briefly reasserted claims in 1562 by occupying Le Havre, but French forces expelled them in 1563. The Treaty of Troyes in 1564 sealed French ownership for 120,000 crowns, closing the chapter. But let's linger on the human elements, because history isn't just dates and battles—it's people. Francis de Guise was a larger-than-life figure: scarred from Italian wars (earning the nickname "Le Balafré" or "The Scarred"), he was a devout Catholic who later led the ultra-Catholic faction in France's Wars of Religion. His leadership at Calais showcased tactical brilliance—using winter to mask movements, coordinating artillery with infantry assaults, and exploiting intelligence from French spies in the city. One anecdote tells of Guise personally leading a charge, his armor dented by English shot, inspiring his men with shouts of "For France and glory!"

Thomas Wentworth, meanwhile, was no coward. Descended from a noble family, he had served in prior campaigns. Post-siege, he faced a court-martial in England but was acquitted, blamed instead on inadequate support from London. Civilians in Calais, many English-born, faced upheaval: families uprooted, livelihoods lost. French records note orderly evacuations, with boats ferrying thousands across the Channel amid tears and farewells. Some stayed, assimilating into French society, their descendants perhaps still in the region today.

The siege's tactics were innovative for the time. Guise employed gabions—wicker baskets filled with earth—for quick fortifications against counter-fire. Engineers like those trained under Italian masters directed the mining operations, collapsing walls with precise powder charges. On the English side, attempts to flood approaches backfired when French captured the sluices, turning the marshes into a moat favoring the besiegers. Weather added drama: soldiers endured frostbite, with campfires dotting the night like stars, while inside Calais, rations stretched thin as hope faded.

Zooming out, Calais's fall reflected broader shifts. The Renaissance was in full swing, with humanism challenging medieval chivalry. Gunpowder democratized warfare, allowing smaller states to challenge empires. In England, it accelerated the Tudor centralization of power, as Mary and later Elizabeth focused on internal reforms. France, under the Valois, solidified northern borders, paving the way for absolutism under the Bourbons.

Historians debate the siege's inevitability. Some argue English neglect—Mary's focus on religious persecution and Spanish alliances—doomed Calais. Others praise Guise's audacity, noting how a summer campaign might have drawn English reinforcements. Contemporary accounts, like those from French chronicler Martin du Bellay or English diplomat Nicholas Wotton, paint vivid pictures: du Bellay describes the "thunder of cannons shaking the earth," while Wotton lamented the "sudden and unlooked-for" loss in dispatches to London.

But let's linger on the human elements, because history isn't just dates and battles—it's people. Francis de Guise was a larger-than-life figure: scarred from Italian wars (earning the nickname "Le Balafré" or "The Scarred"), he was a devout Catholic who later led the ultra-Catholic faction in France's Wars of Religion. His leadership at Calais showcased tactical brilliance—using winter to mask movements, coordinating artillery with infantry assaults, and exploiting intelligence from French spies in the city. One anecdote tells of Guise personally leading a charge, his armor dented by English shot, inspiring his men with shouts of "For France and glory!"

Thomas Wentworth, meanwhile, was no coward. Descended from a noble family, he had served in prior campaigns. Post-siege, he faced a court-martial in England but was acquitted, blamed instead on inadequate support from London. Civilians in Calais, many English-born, faced upheaval: families uprooted, livelihoods lost. French records note orderly evacuations, with boats ferrying thousands across the Channel amid tears and farewells. Some stayed, assimilating into French society, their descendants perhaps still in the region today.

The siege's tactics were innovative for the time. Guise employed gabions—wicker baskets filled with earth—for quick fortifications against counter-fire. Engineers like those trained under Italian masters directed the mining operations, collapsing walls with precise powder charges. On the English side, attempts to flood approaches backfired when French captured the sluices, turning the marshes into a moat favoring the besiegers. Weather added drama: soldiers endured frostbite, with campfires dotting the night like stars, while inside Calais, rations stretched thin as hope faded.

Zooming out, Calais's fall reflected broader shifts. The Renaissance was in full swing, with humanism challenging medieval chivalry. Gunpowder democratized warfare, allowing smaller states to challenge empires. In England, it accelerated the Tudor centralization of power, as Mary and later Elizabeth focused on internal reforms. France, under the Valois, solidified northern borders, paving the way for absolutism under the Bourbons.

Historians debate the siege's inevitability. Some argue English neglect—Mary's focus on religious persecution and Spanish alliances—doomed Calais. Others praise Guise's audacity, noting how a summer campaign might have drawn English reinforcements. Contemporary accounts, like those from French chronicler Martin du Bellay or English diplomat Nicholas Wotton, paint vivid pictures: du Bellay describes the "thunder of cannons shaking the earth," while Wotton lamented the "sudden and unlooked-for" loss in dispatches to London. The cultural impact lingered. Shakespeare's plays reference Calais obliquely, symbolizing lost glory. In France, ballads celebrated Guise as a national savior. Artworks, like engravings by Frans Hogenberg, depicted the siege's chaos, influencing later military illustrations. Even today, Calais's architecture bears scars—remnants of walls and forts whisper of 1558's drama.

Shifting gears from the past's powder smoke, let's extract the gold from this historical nugget. The French victory at Calais wasn't luck; it was the culmination of patience, preparation, and pouncing on opportunity. England’s defeat, while crushing, forced reinvention. In our lives, we all face "lost Calaises"—dreams deferred, jobs lost, relationships ended. But like France reclaiming its soil, or England pivoting to naval supremacy, we can turn reversals into rallies. Here's how this 1558 saga inspires modern action, with a motivational twist: view your challenges as sieges to conquer, not walls to hide behind.

- **Embrace Strategic Surprise in Daily Decisions**: Just as Guise struck in winter when least expected, inject unpredictability into your routine. For career growth, apply for that promotion during a company lull, or network at an off-season event. In health, start a fitness regime in January when gyms are packed with resolvers, but twist it by choosing unconventional activities like winter hiking to build resilience against cold-weather excuses.

- **Build Your Defenses Before the Storm**: Wentworth's underfunded walls highlight preparation's power. Apply this by auditing your finances quarterly—set aside an emergency fund equivalent to three months' expenses, invested in low-risk bonds. For mental health, fortify with daily journaling: spend 10 minutes noting gratitudes and potential stressors, creating a "moat" against anxiety.

- **Leverage Overwhelming Force on Goals**: Guise's 27,000 troops overwhelmed 2,500 defenders. In personal development, mass your resources on one objective at a time. If aiming for a skill like public speaking, dedicate 20 hours weekly: join Toastmasters, practice speeches thrice daily, and record sessions for feedback, ensuring breakthrough rather than scattered efforts.

- **Turn Setbacks into Strategic Pivots**: England's loss shifted focus to the seas, birthing an empire. After a failure—like a failed business venture—pivot by analyzing what went wrong in a "post-siege review": list three lessons, then redirect energy to a related but safer path, such as consulting in your failed niche instead of starting anew.

- **Cultivate Leadership Like Guise**: The duke's personal charges motivated troops. In your life, lead by example: if family fitness is the goal, initiate group walks, sharing historical tidbits like this siege to make it fun. At work, volunteer for tough projects, inspiring colleagues with your enthusiasm.

- **Secure Your "Booty" Post-Victory**: French spoils sustained them. After achievements, reward sustainably: post-promotion, allocate 10% of the raise to a passion project, like travel inspired by historical sites, ensuring long-term motivation.

- **Negotiate Honorable Terms in Conflicts**: Wentworth's surrender saved lives. In arguments, seek win-win: during a relationship spat, propose compromises like "I hear your point; let's try my idea for a week and reassess," preserving bonds like Guise spared civilians.

Now, a step-by-step plan to apply Calais's lessons to your life over the next month, turning history into habit:

The cultural impact lingered. Shakespeare's plays reference Calais obliquely, symbolizing lost glory. In France, ballads celebrated Guise as a national savior. Artworks, like engravings by Frans Hogenberg, depicted the siege's chaos, influencing later military illustrations. Even today, Calais's architecture bears scars—remnants of walls and forts whisper of 1558's drama.

Shifting gears from the past's powder smoke, let's extract the gold from this historical nugget. The French victory at Calais wasn't luck; it was the culmination of patience, preparation, and pouncing on opportunity. England’s defeat, while crushing, forced reinvention. In our lives, we all face "lost Calaises"—dreams deferred, jobs lost, relationships ended. But like France reclaiming its soil, or England pivoting to naval supremacy, we can turn reversals into rallies. Here's how this 1558 saga inspires modern action, with a motivational twist: view your challenges as sieges to conquer, not walls to hide behind.

- **Embrace Strategic Surprise in Daily Decisions**: Just as Guise struck in winter when least expected, inject unpredictability into your routine. For career growth, apply for that promotion during a company lull, or network at an off-season event. In health, start a fitness regime in January when gyms are packed with resolvers, but twist it by choosing unconventional activities like winter hiking to build resilience against cold-weather excuses.

- **Build Your Defenses Before the Storm**: Wentworth's underfunded walls highlight preparation's power. Apply this by auditing your finances quarterly—set aside an emergency fund equivalent to three months' expenses, invested in low-risk bonds. For mental health, fortify with daily journaling: spend 10 minutes noting gratitudes and potential stressors, creating a "moat" against anxiety.

- **Leverage Overwhelming Force on Goals**: Guise's 27,000 troops overwhelmed 2,500 defenders. In personal development, mass your resources on one objective at a time. If aiming for a skill like public speaking, dedicate 20 hours weekly: join Toastmasters, practice speeches thrice daily, and record sessions for feedback, ensuring breakthrough rather than scattered efforts.

- **Turn Setbacks into Strategic Pivots**: England's loss shifted focus to the seas, birthing an empire. After a failure—like a failed business venture—pivot by analyzing what went wrong in a "post-siege review": list three lessons, then redirect energy to a related but safer path, such as consulting in your failed niche instead of starting anew.

- **Cultivate Leadership Like Guise**: The duke's personal charges motivated troops. In your life, lead by example: if family fitness is the goal, initiate group walks, sharing historical tidbits like this siege to make it fun. At work, volunteer for tough projects, inspiring colleagues with your enthusiasm.

- **Secure Your "Booty" Post-Victory**: French spoils sustained them. After achievements, reward sustainably: post-promotion, allocate 10% of the raise to a passion project, like travel inspired by historical sites, ensuring long-term motivation.

- **Negotiate Honorable Terms in Conflicts**: Wentworth's surrender saved lives. In arguments, seek win-win: during a relationship spat, propose compromises like "I hear your point; let's try my idea for a week and reassess," preserving bonds like Guise spared civilians.

Now, a step-by-step plan to apply Calais's lessons to your life over the next month, turning history into habit:

**Week 1: Assess Your 'Calais'**: Identify a "lost territory"—a goal you've abandoned. Journal for 15 minutes daily: What caused the setback? What resources do you need to reclaim it? End with one actionable step, like researching courses for a stalled career shift.

**Week 2: Prepare Your Forces**: Gather tools. For health, stock your kitchen with nutritious staples and schedule workouts. Motivate with a playlist of epic soundtracks, imagining Guise's march. Track progress in an app, celebrating small wins with a treat.

**Week 3: Launch the Assault**: Execute with surprise. Tackle the goal head-on: if it's writing a book, commit to 500 words daily at an unusual time, like dawn. Use accountability—share updates with a friend, channeling Wentworth's rally cries.

**Week 4: Secure and Pivot**: Evaluate outcomes. If successful, "claim your booty" by reflecting on gains. If not, pivot: adjust strategies based on learnings, like England did post-loss. End the month with a review session, planning the next "siege."

This 1558 drama reminds us that history isn't a relic—it's rocket fuel. The fall of Calais closed one door but opened oceans of possibility. So, grab your metaphorical cannon, charge forward, and reclaim your ground. The past cheers you on!

By the 1550s, however, the world had shifted. England was under the rule of Queen Mary I, a devout Catholic whose marriage to Philip II of Spain in 1554 tied her realm to the sprawling Habsburg empire. This union wasn't just romantic; it was geopolitical dynamite. Spain and France were locked in the Italian Wars, a series of conflicts over control of Italian states that had simmered since 1494. When France, under King Henry II, invaded Spanish territories in Italy in 1557 at the urging of Pope Paul IV, England was dragged in on Spain's side. Mary's government declared war on France in June 1557, committing troops to support Philip's campaigns. This was a risky move for a nation already strained by religious turmoil—the Protestant Reformation was tearing at England's seams—and economic woes. The catalyst for the siege was the disastrous Battle of St. Quentin in August 1557. There, Spanish forces crushed the French army, capturing key leaders like Constable Anne de Montmorency and leaving the road to Paris vulnerable. Henry II, desperate to regroup, recalled his top commander, Francis, Duke of Guise, from Italy. Guise, a battle-hardened noble from the powerful House of Lorraine, was promoted to lieutenant-general of France. With the French heartland exposed, Henry couldn't afford an open invasion route, but he saw an opportunity in England's distraction. Calais, long a thorn in France's side, became the target. It wasn't just about revenge; reclaiming Calais would boost French morale, secure the northern border, and humiliate England, potentially forcing them out of the war. Guise's plan was masterful in its secrecy and timing. Winter sieges were rare in the 16th century—harsh weather bogged down armies, froze supplies, and sapped morale. But Guise bet on surprise. In late December 1557, he assembled an army of about 27,000 men—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—at key points like Compiègne, Montreuil-sur-Mer, and Boulogne-sur-Mer. The force included Swiss mercenaries, known for their pike formations, and seasoned French troops fresh from Italian campaigns. Artillery was crucial: Guise brought heavy cannons capable of breaching medieval walls, a nod to the evolving gunpowder warfare that was revolutionizing sieges. On the English side, Calais was governed by Thomas Wentworth, 2nd Baron Wentworth, a capable but under-resourced administrator. The garrison numbered around 2,500 men, a mix of professional soldiers, local militia, and mercenaries. Defenses were formidable on paper: the city was ringed by thick stone walls, bastions, and a moat fed by the sea. Outlying forts like Risban (guarding the harbor) and Nieullay (protecting the western approaches) formed a layered defense. But years of neglect had taken a toll. Funds from London were sporadic, walls were crumbling in places, and the marshy terrain, while a natural barrier, could turn treacherous in winter floods. Wentworth had warned Queen Mary of vulnerabilities, but reinforcements were slow amid England's internal strife.

The assault began on New Year's Day, January 1, 1558. Guise's vanguard, under his brother Claude, Duke of Aumale, swept in from the south and west, investing the villages of Sangatte, Fréthun, and Nielles-lès-Calais. These moves cut off English supply lines and isolated the outposts. The French artillery, dragged through frozen mud, targeted Fort Risban first. This squat, round tower controlled the harbor entrance, preventing English ships from resupplying the city. By January 2, bombardment had begun in earnest. Cannonballs smashed into the fort's walls, while French infantry stormed the breaches under cover of arquebus fire. The defenders, led by a small contingent, fought fiercely but were overwhelmed. Risban fell that day, its garrison slaughtered or captured. With the harbor secured, Guise turned to Fort Nieullay (also called Risbank) on January 3. This fort, built on a sandy spit, was crucial for controlling the sluices that flooded the marshes around Calais, a defensive tactic to drown attackers. French engineers, experts in siegecraft from years in Italy, positioned batteries close and pounded the structure. Explosions of gunpowder mines undermined the walls, and by evening, Nieullay too was in French hands. Now, the path to Calais proper was open. Guise's main force encircled the city, digging trenches and erecting earthworks despite the freezing conditions. Sappers tunneled under the walls, placing charges to create breaches. Inside Calais, panic set in. Wentworth rallied his men, repairing defenses and manning the ramparts. Archers and gunners fired back, but French artillery superiority told. On January 4 and 5, heavy barrages targeted the city's gates and towers. The Castle Gate, a key entry point, was reduced to rubble. French assaults probed the walls, with ladders and scaling parties braving English crossbow bolts and boiling oil. The weather played a role: a sudden thaw turned the ground to slush, hindering movement but also flooding low-lying areas, which Guise used to his advantage by channeling water to isolate sections of the defense. By January 6, the situation was dire. Breaches gaped in multiple walls, and English ammunition was running low. Wentworth sent desperate pleas for aid to England, but the Channel storms delayed any relief fleet. That night, Guise ordered a general assault. French troops, shouting battle cries, surged forward under cover of darkness. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued on the ramparts—pikes clashing with halberds, swords ringing against armor. The English held some positions, but exhaustion and numbers favored the attackers.

Dawn on January 7 revealed the inevitable. With French forces inside the outer defenses and no hope of reinforcement, Wentworth sued for terms. Guise, ever the chivalrous commander, granted honorable surrender: no massacre, safe passage for civilians and soldiers back to England. Wentworth handed over the keys of the city that afternoon, marking the formal capitulation. The French entered Calais triumphantly, discovering vast stores—food for three months, nearly 300 cannons, and stockpiles of arms. Booty was immense, including tapestries, silver, and wine cellars that reportedly kept the victors merry for days. The fall didn't stop there. Nearby English-held castles at Guînes and Hammes fell within weeks. Guise pressed on, but Henry II recalled him to counter Spanish threats elsewhere. On January 23, the French king made a grand entry into Calais, declaring it "reclaimed land" and ordering reconstructions. Borders were redrawn, parishes reorganized, and villages rebuilt, integrating the area fully into France. The shockwaves rippled across Europe. In England, the loss was a national trauma. Queen Mary, already ill, is said to have lamented on her deathbed that "when I am dead and opened, you shall find 'Philip' and 'Calais' lying in my heart." It fueled anti-Spanish sentiment, as many blamed Philip for dragging England into a war that cost them dearly. Economically, the wool trade suffered, shifting focus to Antwerp. Militarily, it forced England to rethink defenses, emphasizing naval power over continental footholds—a pivot that foreshadowed the Elizabethan era's maritime dominance. For France, it was a morale booster amid defeats. Guise emerged a hero, his lightning campaign studied in military academies for centuries. The siege highlighted gunpowder's role in ending medieval fortifications, accelerating fortress designs like the trace italienne. Politically, it hastened the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, ending the Italian Wars. England nominally retained rights to Calais, but France's payment of 500,000 gold crowns never fully materialized. Elizabeth I, Mary's successor, briefly reasserted claims in 1562 by occupying Le Havre, but French forces expelled them in 1563. The Treaty of Troyes in 1564 sealed French ownership for 120,000 crowns, closing the chapter.

But let's linger on the human elements, because history isn't just dates and battles—it's people. Francis de Guise was a larger-than-life figure: scarred from Italian wars (earning the nickname "Le Balafré" or "The Scarred"), he was a devout Catholic who later led the ultra-Catholic faction in France's Wars of Religion. His leadership at Calais showcased tactical brilliance—using winter to mask movements, coordinating artillery with infantry assaults, and exploiting intelligence from French spies in the city. One anecdote tells of Guise personally leading a charge, his armor dented by English shot, inspiring his men with shouts of "For France and glory!" Thomas Wentworth, meanwhile, was no coward. Descended from a noble family, he had served in prior campaigns. Post-siege, he faced a court-martial in England but was acquitted, blamed instead on inadequate support from London. Civilians in Calais, many English-born, faced upheaval: families uprooted, livelihoods lost. French records note orderly evacuations, with boats ferrying thousands across the Channel amid tears and farewells. Some stayed, assimilating into French society, their descendants perhaps still in the region today. The siege's tactics were innovative for the time. Guise employed gabions—wicker baskets filled with earth—for quick fortifications against counter-fire. Engineers like those trained under Italian masters directed the mining operations, collapsing walls with precise powder charges. On the English side, attempts to flood approaches backfired when French captured the sluices, turning the marshes into a moat favoring the besiegers. Weather added drama: soldiers endured frostbite, with campfires dotting the night like stars, while inside Calais, rations stretched thin as hope faded. Zooming out, Calais's fall reflected broader shifts. The Renaissance was in full swing, with humanism challenging medieval chivalry. Gunpowder democratized warfare, allowing smaller states to challenge empires. In England, it accelerated the Tudor centralization of power, as Mary and later Elizabeth focused on internal reforms. France, under the Valois, solidified northern borders, paving the way for absolutism under the Bourbons. Historians debate the siege's inevitability. Some argue English neglect—Mary's focus on religious persecution and Spanish alliances—doomed Calais. Others praise Guise's audacity, noting how a summer campaign might have drawn English reinforcements. Contemporary accounts, like those from French chronicler Martin du Bellay or English diplomat Nicholas Wotton, paint vivid pictures: du Bellay describes the "thunder of cannons shaking the earth," while Wotton lamented the "sudden and unlooked-for" loss in dispatches to London.

The cultural impact lingered. Shakespeare's plays reference Calais obliquely, symbolizing lost glory. In France, ballads celebrated Guise as a national savior. Artworks, like engravings by Frans Hogenberg, depicted the siege's chaos, influencing later military illustrations. Even today, Calais's architecture bears scars—remnants of walls and forts whisper of 1558's drama. Shifting gears from the past's powder smoke, let's extract the gold from this historical nugget. The French victory at Calais wasn't luck; it was the culmination of patience, preparation, and pouncing on opportunity. England’s defeat, while crushing, forced reinvention. In our lives, we all face "lost Calaises"—dreams deferred, jobs lost, relationships ended. But like France reclaiming its soil, or England pivoting to naval supremacy, we can turn reversals into rallies. Here's how this 1558 saga inspires modern action, with a motivational twist: view your challenges as sieges to conquer, not walls to hide behind. - **Embrace Strategic Surprise in Daily Decisions**: Just as Guise struck in winter when least expected, inject unpredictability into your routine. For career growth, apply for that promotion during a company lull, or network at an off-season event. In health, start a fitness regime in January when gyms are packed with resolvers, but twist it by choosing unconventional activities like winter hiking to build resilience against cold-weather excuses. - **Build Your Defenses Before the Storm**: Wentworth's underfunded walls highlight preparation's power. Apply this by auditing your finances quarterly—set aside an emergency fund equivalent to three months' expenses, invested in low-risk bonds. For mental health, fortify with daily journaling: spend 10 minutes noting gratitudes and potential stressors, creating a "moat" against anxiety. - **Leverage Overwhelming Force on Goals**: Guise's 27,000 troops overwhelmed 2,500 defenders. In personal development, mass your resources on one objective at a time. If aiming for a skill like public speaking, dedicate 20 hours weekly: join Toastmasters, practice speeches thrice daily, and record sessions for feedback, ensuring breakthrough rather than scattered efforts. - **Turn Setbacks into Strategic Pivots**: England's loss shifted focus to the seas, birthing an empire. After a failure—like a failed business venture—pivot by analyzing what went wrong in a "post-siege review": list three lessons, then redirect energy to a related but safer path, such as consulting in your failed niche instead of starting anew. - **Cultivate Leadership Like Guise**: The duke's personal charges motivated troops. In your life, lead by example: if family fitness is the goal, initiate group walks, sharing historical tidbits like this siege to make it fun. At work, volunteer for tough projects, inspiring colleagues with your enthusiasm. - **Secure Your "Booty" Post-Victory**: French spoils sustained them. After achievements, reward sustainably: post-promotion, allocate 10% of the raise to a passion project, like travel inspired by historical sites, ensuring long-term motivation. - **Negotiate Honorable Terms in Conflicts**: Wentworth's surrender saved lives. In arguments, seek win-win: during a relationship spat, propose compromises like "I hear your point; let's try my idea for a week and reassess," preserving bonds like Guise spared civilians. Now, a step-by-step plan to apply Calais's lessons to your life over the next month, turning history into habit: