Imagine a foggy December morning in 1606, along the bustling docks of Blackwall in London. The air is thick with the scent of tar, saltwater, and unbridled optimism. Three modest wooden ships bob gently in the Thames, their sails furled, decks crammed with supplies, and holds filled with dreamers ready to chase fortune across a vast, unknown ocean. This wasn't just any voyage—it was the spark that ignited England's colonial empire in the New World. On December 20, 1606, the Virginia Company of London set sail on a mission that would reshape history, planting the seeds for what would become the United States. But this story isn't a tidy tale of triumph; it's a gritty saga of ambition, hardship, and sheer human grit. Dive in with me as we unpack the intricate details of this pivotal moment, exploring the political intrigue, the perilous journey, the brutal realities of early settlement, and the profound ripples it sent through centuries. And stick around—because we'll distill these ancient echoes into a motivational blueprint you can apply right now to navigate your own life's uncharted waters. Let's start at the beginning, rewinding to the turbulent world of early 17th-century England. King James I had ascended the throne just three years earlier in 1603, uniting England and Scotland under one crown but inheriting a realm rife with economic pressures, religious tensions, and imperial envy. Europe was ablaze with colonial fever. Spain had already amassed staggering wealth from its New World conquests—think mountains of silver from Potosí and gold from Aztec ruins—fueling England's desire to catch up. The English had dabbled in overseas ventures before: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's ill-fated Newfoundland expedition in 1583, Sir Walter Raleigh's doomed Roanoke colony in the 1580s (the infamous "Lost Colony" that vanished without a trace). These failures stung, but they also taught valuable lessons about the perils of underfunded, poorly planned adventures.

Enter the Virginia Company. Formed as a joint-stock enterprise—a novel business model where investors pooled resources and shared risks—this group of London merchants, nobles, and adventurers sought royal approval to stake a claim in North America. On April 10, 1606, King James granted them a charter, dividing the potential territories between two branches: the Virginia Company of London (for the southern region, roughly from modern-day North Carolina to New York) and the Plymouth Company (for the north). The charter's language was grand and sweeping, authorizing the company to "plant" colonies, mine for precious metals, trade with natives, and propagate the Protestant faith among "savages and barbarous people." But beneath the lofty rhetoric lay pragmatic goals: profit from gold, silver, or a northwest passage to Asia; relieve England's overpopulation by shipping off the unemployed and restless; and establish a strategic foothold to challenge Spanish dominance.

The company's investors were a who's who of London's elite. Figures like Sir Thomas Smythe, a wealthy merchant and future governor of the East India Company, poured in funds. They recruited colonists from diverse backgrounds: gentlemen seeking adventure and status, skilled craftsmen like carpenters and blacksmiths, laborers for the grunt work, and even a few boys as servants or apprentices. Notably absent were women and families—this was a male-dominated venture focused on extraction and survival, not long-term settlement. The total number of passengers hovered around 104 to 105, plus a crew of about 39 sailors, making for cramped quarters on ships that were tiny by modern standards.

The fleet consisted of three vessels, each with its own character and captain. The flagship, Susan Constant, was the largest at about 120 tons, commanded by the experienced mariner Christopher Newport. A one-armed veteran of privateering raids against the Spanish (he'd lost his limb in a Caribbean skirmish), Newport was chosen for his navigational prowess and leadership. The Godspeed, around 40 tons, was captained by Bartholomew Gosnold, an explorer who'd previously scouted New England in 1602 and named Cape Cod. The smallest, the pinnace Discovery at 20 tons, fell under John Ratcliffe (a pseudonym for John Sicklemore), a less distinguished but capable seaman. These ships were typical of the era: wooden hulls reinforced with oak, square-rigged sails for ocean winds, and rudimentary navigation tools like compasses, astrolabes, and lead lines for sounding depths.

Preparations for departure were meticulous yet fraught with delays. The company had to secure provisions—barrels of salted pork, beef, fish, biscuits, cheese, beer (safer than water), and oatmeal—enough for a projected three-month crossing, though reality would prove harsher. Tools for building, weapons for defense (muskets, swords, and armor), trade goods like beads and copper for natives, and even seeds for planting crops were loaded aboard. Sealed instructions from the company council, to be opened only after crossing the Atlantic, named the colonial leaders: a seven-man council including Newport, Gosnold, Ratcliffe, Edward Maria Wingfield (a soldier and investor), George Kendall, John Martin, and the soon-to-be-famous John Smith.

Why December 20? Winter departures were risky due to stormy Atlantic weather, but urgency drove the decision. Rival powers were moving fast—France had founded Quebec in 1608, but rumors of Spanish encroachments spurred action. The ships had been ready since autumn, but winds and tides delayed them. Finally, on that crisp December day (sources vary between the 19th and 20th, likely due to old-style Julian calendar discrepancies), the fleet cast off from Blackwall, a shipyard east of London. Crowds gathered to wave farewell, trumpets blared, and prayers were offered for safe passage. As the ships navigated down the Thames toward the English Channel, no one could foresee the trials ahead.

The voyage itself was a four-and-a-half-month odyssey of endurance. Leaving England, they hugged the coast southward, stopping briefly in the Downs (off Kent) before braving the open sea. Storms battered them almost immediately, scattering the fleet and forcing a retreat to Plymouth for repairs. Reunited, they pressed on, reaching the Canary Islands by mid-January 1607 for fresh water and supplies. From there, the route followed prevailing trade winds: southwest to the Caribbean. They sighted Dominica on March 23, then hopped through the Virgin Islands (which they named), enduring heat, scurvy outbreaks, and rationing as food spoiled.

Tensions simmered aboard. John Smith, a boastful mercenary with experience in European wars and Ottoman captivity, clashed with Wingfield and others. Accused of mutiny, he was confined in irons for much of the trip. Meanwhile, the passengers—unaccustomed to ship life—suffered from seasickness, cramped conditions, and boredom. Games of dice, storytelling, and religious services provided diversion, but disease claimed lives; at least one colonist died en route.

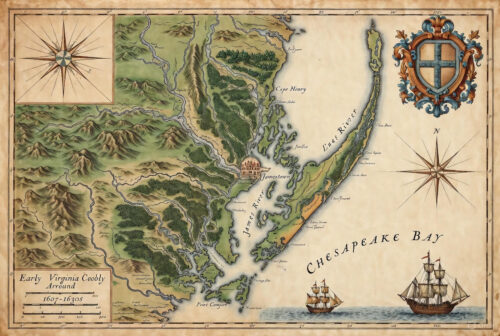

Arriving at the Chesapeake Bay on April 26, 1607, they explored the coastline, naming Cape Henry after the king's son. A skirmish with natives at Cape Comfort foreshadowed conflicts. On May 13, they anchored at a marshy peninsula 60 miles up the James River (named for the king), deeming it defensible against Spanish ships. The next day, May 14, they disembarked and began fortifying Jamestown—named for James I.

Let's start at the beginning, rewinding to the turbulent world of early 17th-century England. King James I had ascended the throne just three years earlier in 1603, uniting England and Scotland under one crown but inheriting a realm rife with economic pressures, religious tensions, and imperial envy. Europe was ablaze with colonial fever. Spain had already amassed staggering wealth from its New World conquests—think mountains of silver from Potosí and gold from Aztec ruins—fueling England's desire to catch up. The English had dabbled in overseas ventures before: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's ill-fated Newfoundland expedition in 1583, Sir Walter Raleigh's doomed Roanoke colony in the 1580s (the infamous "Lost Colony" that vanished without a trace). These failures stung, but they also taught valuable lessons about the perils of underfunded, poorly planned adventures.

Enter the Virginia Company. Formed as a joint-stock enterprise—a novel business model where investors pooled resources and shared risks—this group of London merchants, nobles, and adventurers sought royal approval to stake a claim in North America. On April 10, 1606, King James granted them a charter, dividing the potential territories between two branches: the Virginia Company of London (for the southern region, roughly from modern-day North Carolina to New York) and the Plymouth Company (for the north). The charter's language was grand and sweeping, authorizing the company to "plant" colonies, mine for precious metals, trade with natives, and propagate the Protestant faith among "savages and barbarous people." But beneath the lofty rhetoric lay pragmatic goals: profit from gold, silver, or a northwest passage to Asia; relieve England's overpopulation by shipping off the unemployed and restless; and establish a strategic foothold to challenge Spanish dominance.

The company's investors were a who's who of London's elite. Figures like Sir Thomas Smythe, a wealthy merchant and future governor of the East India Company, poured in funds. They recruited colonists from diverse backgrounds: gentlemen seeking adventure and status, skilled craftsmen like carpenters and blacksmiths, laborers for the grunt work, and even a few boys as servants or apprentices. Notably absent were women and families—this was a male-dominated venture focused on extraction and survival, not long-term settlement. The total number of passengers hovered around 104 to 105, plus a crew of about 39 sailors, making for cramped quarters on ships that were tiny by modern standards.

The fleet consisted of three vessels, each with its own character and captain. The flagship, Susan Constant, was the largest at about 120 tons, commanded by the experienced mariner Christopher Newport. A one-armed veteran of privateering raids against the Spanish (he'd lost his limb in a Caribbean skirmish), Newport was chosen for his navigational prowess and leadership. The Godspeed, around 40 tons, was captained by Bartholomew Gosnold, an explorer who'd previously scouted New England in 1602 and named Cape Cod. The smallest, the pinnace Discovery at 20 tons, fell under John Ratcliffe (a pseudonym for John Sicklemore), a less distinguished but capable seaman. These ships were typical of the era: wooden hulls reinforced with oak, square-rigged sails for ocean winds, and rudimentary navigation tools like compasses, astrolabes, and lead lines for sounding depths.

Preparations for departure were meticulous yet fraught with delays. The company had to secure provisions—barrels of salted pork, beef, fish, biscuits, cheese, beer (safer than water), and oatmeal—enough for a projected three-month crossing, though reality would prove harsher. Tools for building, weapons for defense (muskets, swords, and armor), trade goods like beads and copper for natives, and even seeds for planting crops were loaded aboard. Sealed instructions from the company council, to be opened only after crossing the Atlantic, named the colonial leaders: a seven-man council including Newport, Gosnold, Ratcliffe, Edward Maria Wingfield (a soldier and investor), George Kendall, John Martin, and the soon-to-be-famous John Smith.

Why December 20? Winter departures were risky due to stormy Atlantic weather, but urgency drove the decision. Rival powers were moving fast—France had founded Quebec in 1608, but rumors of Spanish encroachments spurred action. The ships had been ready since autumn, but winds and tides delayed them. Finally, on that crisp December day (sources vary between the 19th and 20th, likely due to old-style Julian calendar discrepancies), the fleet cast off from Blackwall, a shipyard east of London. Crowds gathered to wave farewell, trumpets blared, and prayers were offered for safe passage. As the ships navigated down the Thames toward the English Channel, no one could foresee the trials ahead.

The voyage itself was a four-and-a-half-month odyssey of endurance. Leaving England, they hugged the coast southward, stopping briefly in the Downs (off Kent) before braving the open sea. Storms battered them almost immediately, scattering the fleet and forcing a retreat to Plymouth for repairs. Reunited, they pressed on, reaching the Canary Islands by mid-January 1607 for fresh water and supplies. From there, the route followed prevailing trade winds: southwest to the Caribbean. They sighted Dominica on March 23, then hopped through the Virgin Islands (which they named), enduring heat, scurvy outbreaks, and rationing as food spoiled.

Tensions simmered aboard. John Smith, a boastful mercenary with experience in European wars and Ottoman captivity, clashed with Wingfield and others. Accused of mutiny, he was confined in irons for much of the trip. Meanwhile, the passengers—unaccustomed to ship life—suffered from seasickness, cramped conditions, and boredom. Games of dice, storytelling, and religious services provided diversion, but disease claimed lives; at least one colonist died en route.

Arriving at the Chesapeake Bay on April 26, 1607, they explored the coastline, naming Cape Henry after the king's son. A skirmish with natives at Cape Comfort foreshadowed conflicts. On May 13, they anchored at a marshy peninsula 60 miles up the James River (named for the king), deeming it defensible against Spanish ships. The next day, May 14, they disembarked and began fortifying Jamestown—named for James I. The early months were a nightmare. The site, chosen for its strategic depth, was a malarial swamp with brackish water. Mosquitoes spread disease, killing dozens. By September, half the colonists were dead, including Gosnold. Food shortages led to starvation; they traded with Powhatan natives for corn but relations soured. Internal strife peaked: Wingfield was deposed as president, Ratcliffe took over briefly, and Smith emerged as a leader after his release. His famous "he that will not work shall not eat" edict enforced labor, but the "Starving Time" of 1609-1610 would later reduce the population from 500 to 60.

The early months were a nightmare. The site, chosen for its strategic depth, was a malarial swamp with brackish water. Mosquitoes spread disease, killing dozens. By September, half the colonists were dead, including Gosnold. Food shortages led to starvation; they traded with Powhatan natives for corn but relations soured. Internal strife peaked: Wingfield was deposed as president, Ratcliffe took over briefly, and Smith emerged as a leader after his release. His famous "he that will not work shall not eat" edict enforced labor, but the "Starving Time" of 1609-1610 would later reduce the population from 500 to 60. Despite the horrors, Jamestown persevered. Reinforcements arrived in 1608 and 1609, including the ill-fated Third Supply fleet wrecked by a hurricane (inspiring Shakespeare's *The Tempest*). John Rolfe introduced tobacco in 1612, turning it into a cash crop that saved the colony economically. The 1619 arrival of the first African slaves and the House of Burgesses marked shifts toward plantation agriculture and self-governance. By 1624, after a devastating Powhatan uprising in 1622 that killed 347 settlers, the Virginia Company went bankrupt, and Virginia became a royal colony.

This event's significance can't be overstated. Jamestown wasn't just a foothold; it was the blueprint for English expansion in America. It introduced concepts like representative government (the 1619 assembly was the first in the New World), private land ownership, and commercial agriculture. It also set the stage for cultural clashes, slavery, and the displacement of indigenous peoples—dark legacies that shaped the continent's future. Without this voyage, the trajectory of North American history might have veered toward French or Spanish dominance, altering everything from the American Revolution to modern geopolitics.

Now, let's zoom in on the nitty-gritty details that make this history come alive. The ships themselves were marvels of Elizabethan engineering. The Susan Constant, about 100 feet long, had a crew of 71 and carried 54 passengers. Its hold brimmed with 20 tons of provisions, including 8,000 biscuits and 10 barrels of oatmeal. The Godspeed, sleeker at 68 feet, accommodated 52 souls, while the Discovery, a mere 50 feet, squeezed in 21. Navigation relied on dead reckoning—estimating position from speed and direction—supplemented by celestial observations. Errors were common; one storm blew them off course by hundreds of miles.

The passengers' daily life was regimented. Mornings began with prayers led by the chaplain, Rev. Robert Hunt. Meals were sparse: hardtack biscuits, salted meat, and pease porridge. Fresh fish caught en route provided variety. Hygiene was abysmal; lice, rats, and dysentery plagued them. Entertainment included reading from the Bible or Hakluyt's travel narratives, which fueled dreams of golden cities.

Despite the horrors, Jamestown persevered. Reinforcements arrived in 1608 and 1609, including the ill-fated Third Supply fleet wrecked by a hurricane (inspiring Shakespeare's *The Tempest*). John Rolfe introduced tobacco in 1612, turning it into a cash crop that saved the colony economically. The 1619 arrival of the first African slaves and the House of Burgesses marked shifts toward plantation agriculture and self-governance. By 1624, after a devastating Powhatan uprising in 1622 that killed 347 settlers, the Virginia Company went bankrupt, and Virginia became a royal colony.

This event's significance can't be overstated. Jamestown wasn't just a foothold; it was the blueprint for English expansion in America. It introduced concepts like representative government (the 1619 assembly was the first in the New World), private land ownership, and commercial agriculture. It also set the stage for cultural clashes, slavery, and the displacement of indigenous peoples—dark legacies that shaped the continent's future. Without this voyage, the trajectory of North American history might have veered toward French or Spanish dominance, altering everything from the American Revolution to modern geopolitics.

Now, let's zoom in on the nitty-gritty details that make this history come alive. The ships themselves were marvels of Elizabethan engineering. The Susan Constant, about 100 feet long, had a crew of 71 and carried 54 passengers. Its hold brimmed with 20 tons of provisions, including 8,000 biscuits and 10 barrels of oatmeal. The Godspeed, sleeker at 68 feet, accommodated 52 souls, while the Discovery, a mere 50 feet, squeezed in 21. Navigation relied on dead reckoning—estimating position from speed and direction—supplemented by celestial observations. Errors were common; one storm blew them off course by hundreds of miles.

The passengers' daily life was regimented. Mornings began with prayers led by the chaplain, Rev. Robert Hunt. Meals were sparse: hardtack biscuits, salted meat, and pease porridge. Fresh fish caught en route provided variety. Hygiene was abysmal; lice, rats, and dysentery plagued them. Entertainment included reading from the Bible or Hakluyt's travel narratives, which fueled dreams of golden cities. Upon arrival, the sealed box revealed the council, but egos clashed immediately. Wingfield, a haughty aristocrat, favored gentlemen over laborers, exacerbating divisions. Smith's adventures—exploring rivers, trading with Powhatans, and his alleged rescue by Pocahontas (a story he embellished later)—added drama. The natives, part of the Powhatan Confederacy under Chief Wahunsenacawh (Powhatan), initially aided the strangers but grew wary as demands increased.

Economically, the company invested £10,000 (millions today), expecting quick returns. They sent back sassafras (for medicine) and clapboard (timber), but no gold. Tobacco's boom came later, with exports jumping from 2,300 pounds in 1616 to 1.5 million by 1629. Socially, the colony evolved: women arrived in 1608, families in 1619, shifting from a military outpost to a society.

Upon arrival, the sealed box revealed the council, but egos clashed immediately. Wingfield, a haughty aristocrat, favored gentlemen over laborers, exacerbating divisions. Smith's adventures—exploring rivers, trading with Powhatans, and his alleged rescue by Pocahontas (a story he embellished later)—added drama. The natives, part of the Powhatan Confederacy under Chief Wahunsenacawh (Powhatan), initially aided the strangers but grew wary as demands increased.

Economically, the company invested £10,000 (millions today), expecting quick returns. They sent back sassafras (for medicine) and clapboard (timber), but no gold. Tobacco's boom came later, with exports jumping from 2,300 pounds in 1616 to 1.5 million by 1629. Socially, the colony evolved: women arrived in 1608, families in 1619, shifting from a military outpost to a society. Politically, the charter's evolution reflected changing priorities. The 1609 second charter expanded territory and governance, while the 1612 third introduced lotteries to fund the venture—early crowdfunding. By dissolution in 1624, over 6,000 had emigrated, though only 1,200 survived, highlighting the human cost.

Culturally, Jamestown bridged worlds. Artifacts unearthed today—glass beads, iron tools, native pottery—reveal trade and adaptation. The site's archaeology, ongoing since 1994, has uncovered forts, wells, and graves, painting a vivid picture of resilience amid ruin.

Shifting gears from the depths of history, let's bridge this epic to your world today. The Virginia Company's voyage teaches us that bold beginnings, even amid uncertainty, can forge extraordinary paths. Their story of venturing into the unknown mirrors our personal quests—whether starting a career, overcoming setbacks, or chasing dreams. Here's how you can harness these lessons for tangible benefits in your life, with a step-by-step plan to turn historical wisdom into modern momentum.

- **Embrace Calculated Risks for Growth Opportunities:** Just as the company weighed dangers against potential riches, assess your own ventures. For instance, if contemplating a job switch, research market trends, network with industry pros, and pilot small changes like freelance gigs to test waters without full commitment.

- **Build a Diverse Support Network:** The mix of gentlemen, craftsmen, and sailors highlights teamwork's power. In your life, cultivate a circle of mentors, peers, and experts—join professional groups, attend workshops, or use apps like LinkedIn to connect, ensuring varied perspectives fuel your progress.

- **Prepare Thoroughly but Adapt Flexibly:** The colonists' provisions sustained them initially, but adaptation to new environments saved them. Apply this by creating detailed plans for goals (e.g., a fitness regimen with meal preps and workouts), yet remain open to pivots—like switching routines if injuries arise.

- **Learn from Setbacks Without Quitting:** Starvation and disease nearly doomed Jamestown, but persistence prevailed. When facing failures, like a rejected project, analyze errors (journal root causes), seek feedback, and iterate—turning losses into stepping stones.

- **Invest in Long-Term Vision Over Quick Wins:** No gold rush, but tobacco's cultivation paid off. Focus on sustainable habits: save 10% of income monthly for investments, or dedicate weekly time to skill-building courses, compounding efforts for future rewards.

- **Foster Resilience Through Community and Faith:** Prayers and native alliances bolstered morale. Build emotional fortitude by practicing gratitude daily, joining support groups for challenges like weight loss, or meditating to center yourself amid chaos.

- **Innovate in the Face of Adversity:** Rolfe's tobacco hybrid revolutionized the economy. Channel this by experimenting—try new productivity tools if old methods falter, or brainstorm side hustles blending your passions, like turning a hobby into an Etsy shop.

Now, a practical 30-day plan to apply these insights:

Politically, the charter's evolution reflected changing priorities. The 1609 second charter expanded territory and governance, while the 1612 third introduced lotteries to fund the venture—early crowdfunding. By dissolution in 1624, over 6,000 had emigrated, though only 1,200 survived, highlighting the human cost.

Culturally, Jamestown bridged worlds. Artifacts unearthed today—glass beads, iron tools, native pottery—reveal trade and adaptation. The site's archaeology, ongoing since 1994, has uncovered forts, wells, and graves, painting a vivid picture of resilience amid ruin.

Shifting gears from the depths of history, let's bridge this epic to your world today. The Virginia Company's voyage teaches us that bold beginnings, even amid uncertainty, can forge extraordinary paths. Their story of venturing into the unknown mirrors our personal quests—whether starting a career, overcoming setbacks, or chasing dreams. Here's how you can harness these lessons for tangible benefits in your life, with a step-by-step plan to turn historical wisdom into modern momentum.

- **Embrace Calculated Risks for Growth Opportunities:** Just as the company weighed dangers against potential riches, assess your own ventures. For instance, if contemplating a job switch, research market trends, network with industry pros, and pilot small changes like freelance gigs to test waters without full commitment.

- **Build a Diverse Support Network:** The mix of gentlemen, craftsmen, and sailors highlights teamwork's power. In your life, cultivate a circle of mentors, peers, and experts—join professional groups, attend workshops, or use apps like LinkedIn to connect, ensuring varied perspectives fuel your progress.

- **Prepare Thoroughly but Adapt Flexibly:** The colonists' provisions sustained them initially, but adaptation to new environments saved them. Apply this by creating detailed plans for goals (e.g., a fitness regimen with meal preps and workouts), yet remain open to pivots—like switching routines if injuries arise.

- **Learn from Setbacks Without Quitting:** Starvation and disease nearly doomed Jamestown, but persistence prevailed. When facing failures, like a rejected project, analyze errors (journal root causes), seek feedback, and iterate—turning losses into stepping stones.

- **Invest in Long-Term Vision Over Quick Wins:** No gold rush, but tobacco's cultivation paid off. Focus on sustainable habits: save 10% of income monthly for investments, or dedicate weekly time to skill-building courses, compounding efforts for future rewards.

- **Foster Resilience Through Community and Faith:** Prayers and native alliances bolstered morale. Build emotional fortitude by practicing gratitude daily, joining support groups for challenges like weight loss, or meditating to center yourself amid chaos.

- **Innovate in the Face of Adversity:** Rolfe's tobacco hybrid revolutionized the economy. Channel this by experimenting—try new productivity tools if old methods falter, or brainstorm side hustles blending your passions, like turning a hobby into an Etsy shop.

Now, a practical 30-day plan to apply these insights:

**Days 1-5: Assess and Plan:** Reflect on a personal "voyage"—a goal like career advancement. List risks, resources needed, and potential obstacles. Research thoroughly, akin to the company's charter preparations.

**Days 6-10: Assemble Your Crew:** Identify 3-5 people for support. Schedule coffee chats or virtual meets to discuss your goal, gathering advice and accountability.

**Days 11-15: Launch with Preparation:** Stock up on tools—books, apps, or courses. Start small actions, like daily habits building toward your aim, mirroring the fleet's provisioning.

**Days 16-20: Navigate Challenges:** Track progress in a journal. When hurdles hit, adapt strategies without derailing, drawing from the voyage's storms.

**Days 21-25: Innovate and Iterate:** Experiment with one new approach, like a different routine or tool. Evaluate results and refine, echoing tobacco's introduction.

**Days 26-30: Reflect and Sustain:** Review achievements, celebrate wins, and plan next steps. Commit to ongoing resilience practices, ensuring your journey endures like Jamestown's legacy.

This isn't just history—it's a rally cry. The Virginia Company's departure on December 20, 1606, reminds us that from humble, hazardous starts come world-changing outcomes. Channel that spirit, and watch your own story unfold with epic flair.

Let's start at the beginning, rewinding to the turbulent world of early 17th-century England. King James I had ascended the throne just three years earlier in 1603, uniting England and Scotland under one crown but inheriting a realm rife with economic pressures, religious tensions, and imperial envy. Europe was ablaze with colonial fever. Spain had already amassed staggering wealth from its New World conquests—think mountains of silver from Potosí and gold from Aztec ruins—fueling England's desire to catch up. The English had dabbled in overseas ventures before: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's ill-fated Newfoundland expedition in 1583, Sir Walter Raleigh's doomed Roanoke colony in the 1580s (the infamous "Lost Colony" that vanished without a trace). These failures stung, but they also taught valuable lessons about the perils of underfunded, poorly planned adventures. Enter the Virginia Company. Formed as a joint-stock enterprise—a novel business model where investors pooled resources and shared risks—this group of London merchants, nobles, and adventurers sought royal approval to stake a claim in North America. On April 10, 1606, King James granted them a charter, dividing the potential territories between two branches: the Virginia Company of London (for the southern region, roughly from modern-day North Carolina to New York) and the Plymouth Company (for the north). The charter's language was grand and sweeping, authorizing the company to "plant" colonies, mine for precious metals, trade with natives, and propagate the Protestant faith among "savages and barbarous people." But beneath the lofty rhetoric lay pragmatic goals: profit from gold, silver, or a northwest passage to Asia; relieve England's overpopulation by shipping off the unemployed and restless; and establish a strategic foothold to challenge Spanish dominance. The company's investors were a who's who of London's elite. Figures like Sir Thomas Smythe, a wealthy merchant and future governor of the East India Company, poured in funds. They recruited colonists from diverse backgrounds: gentlemen seeking adventure and status, skilled craftsmen like carpenters and blacksmiths, laborers for the grunt work, and even a few boys as servants or apprentices. Notably absent were women and families—this was a male-dominated venture focused on extraction and survival, not long-term settlement. The total number of passengers hovered around 104 to 105, plus a crew of about 39 sailors, making for cramped quarters on ships that were tiny by modern standards. The fleet consisted of three vessels, each with its own character and captain. The flagship, Susan Constant, was the largest at about 120 tons, commanded by the experienced mariner Christopher Newport. A one-armed veteran of privateering raids against the Spanish (he'd lost his limb in a Caribbean skirmish), Newport was chosen for his navigational prowess and leadership. The Godspeed, around 40 tons, was captained by Bartholomew Gosnold, an explorer who'd previously scouted New England in 1602 and named Cape Cod. The smallest, the pinnace Discovery at 20 tons, fell under John Ratcliffe (a pseudonym for John Sicklemore), a less distinguished but capable seaman. These ships were typical of the era: wooden hulls reinforced with oak, square-rigged sails for ocean winds, and rudimentary navigation tools like compasses, astrolabes, and lead lines for sounding depths. Preparations for departure were meticulous yet fraught with delays. The company had to secure provisions—barrels of salted pork, beef, fish, biscuits, cheese, beer (safer than water), and oatmeal—enough for a projected three-month crossing, though reality would prove harsher. Tools for building, weapons for defense (muskets, swords, and armor), trade goods like beads and copper for natives, and even seeds for planting crops were loaded aboard. Sealed instructions from the company council, to be opened only after crossing the Atlantic, named the colonial leaders: a seven-man council including Newport, Gosnold, Ratcliffe, Edward Maria Wingfield (a soldier and investor), George Kendall, John Martin, and the soon-to-be-famous John Smith. Why December 20? Winter departures were risky due to stormy Atlantic weather, but urgency drove the decision. Rival powers were moving fast—France had founded Quebec in 1608, but rumors of Spanish encroachments spurred action. The ships had been ready since autumn, but winds and tides delayed them. Finally, on that crisp December day (sources vary between the 19th and 20th, likely due to old-style Julian calendar discrepancies), the fleet cast off from Blackwall, a shipyard east of London. Crowds gathered to wave farewell, trumpets blared, and prayers were offered for safe passage. As the ships navigated down the Thames toward the English Channel, no one could foresee the trials ahead. The voyage itself was a four-and-a-half-month odyssey of endurance. Leaving England, they hugged the coast southward, stopping briefly in the Downs (off Kent) before braving the open sea. Storms battered them almost immediately, scattering the fleet and forcing a retreat to Plymouth for repairs. Reunited, they pressed on, reaching the Canary Islands by mid-January 1607 for fresh water and supplies. From there, the route followed prevailing trade winds: southwest to the Caribbean. They sighted Dominica on March 23, then hopped through the Virgin Islands (which they named), enduring heat, scurvy outbreaks, and rationing as food spoiled. Tensions simmered aboard. John Smith, a boastful mercenary with experience in European wars and Ottoman captivity, clashed with Wingfield and others. Accused of mutiny, he was confined in irons for much of the trip. Meanwhile, the passengers—unaccustomed to ship life—suffered from seasickness, cramped conditions, and boredom. Games of dice, storytelling, and religious services provided diversion, but disease claimed lives; at least one colonist died en route. Arriving at the Chesapeake Bay on April 26, 1607, they explored the coastline, naming Cape Henry after the king's son. A skirmish with natives at Cape Comfort foreshadowed conflicts. On May 13, they anchored at a marshy peninsula 60 miles up the James River (named for the king), deeming it defensible against Spanish ships. The next day, May 14, they disembarked and began fortifying Jamestown—named for James I.

The early months were a nightmare. The site, chosen for its strategic depth, was a malarial swamp with brackish water. Mosquitoes spread disease, killing dozens. By September, half the colonists were dead, including Gosnold. Food shortages led to starvation; they traded with Powhatan natives for corn but relations soured. Internal strife peaked: Wingfield was deposed as president, Ratcliffe took over briefly, and Smith emerged as a leader after his release. His famous "he that will not work shall not eat" edict enforced labor, but the "Starving Time" of 1609-1610 would later reduce the population from 500 to 60.

Despite the horrors, Jamestown persevered. Reinforcements arrived in 1608 and 1609, including the ill-fated Third Supply fleet wrecked by a hurricane (inspiring Shakespeare's *The Tempest*). John Rolfe introduced tobacco in 1612, turning it into a cash crop that saved the colony economically. The 1619 arrival of the first African slaves and the House of Burgesses marked shifts toward plantation agriculture and self-governance. By 1624, after a devastating Powhatan uprising in 1622 that killed 347 settlers, the Virginia Company went bankrupt, and Virginia became a royal colony. This event's significance can't be overstated. Jamestown wasn't just a foothold; it was the blueprint for English expansion in America. It introduced concepts like representative government (the 1619 assembly was the first in the New World), private land ownership, and commercial agriculture. It also set the stage for cultural clashes, slavery, and the displacement of indigenous peoples—dark legacies that shaped the continent's future. Without this voyage, the trajectory of North American history might have veered toward French or Spanish dominance, altering everything from the American Revolution to modern geopolitics. Now, let's zoom in on the nitty-gritty details that make this history come alive. The ships themselves were marvels of Elizabethan engineering. The Susan Constant, about 100 feet long, had a crew of 71 and carried 54 passengers. Its hold brimmed with 20 tons of provisions, including 8,000 biscuits and 10 barrels of oatmeal. The Godspeed, sleeker at 68 feet, accommodated 52 souls, while the Discovery, a mere 50 feet, squeezed in 21. Navigation relied on dead reckoning—estimating position from speed and direction—supplemented by celestial observations. Errors were common; one storm blew them off course by hundreds of miles. The passengers' daily life was regimented. Mornings began with prayers led by the chaplain, Rev. Robert Hunt. Meals were sparse: hardtack biscuits, salted meat, and pease porridge. Fresh fish caught en route provided variety. Hygiene was abysmal; lice, rats, and dysentery plagued them. Entertainment included reading from the Bible or Hakluyt's travel narratives, which fueled dreams of golden cities.

Upon arrival, the sealed box revealed the council, but egos clashed immediately. Wingfield, a haughty aristocrat, favored gentlemen over laborers, exacerbating divisions. Smith's adventures—exploring rivers, trading with Powhatans, and his alleged rescue by Pocahontas (a story he embellished later)—added drama. The natives, part of the Powhatan Confederacy under Chief Wahunsenacawh (Powhatan), initially aided the strangers but grew wary as demands increased. Economically, the company invested £10,000 (millions today), expecting quick returns. They sent back sassafras (for medicine) and clapboard (timber), but no gold. Tobacco's boom came later, with exports jumping from 2,300 pounds in 1616 to 1.5 million by 1629. Socially, the colony evolved: women arrived in 1608, families in 1619, shifting from a military outpost to a society.

Politically, the charter's evolution reflected changing priorities. The 1609 second charter expanded territory and governance, while the 1612 third introduced lotteries to fund the venture—early crowdfunding. By dissolution in 1624, over 6,000 had emigrated, though only 1,200 survived, highlighting the human cost. Culturally, Jamestown bridged worlds. Artifacts unearthed today—glass beads, iron tools, native pottery—reveal trade and adaptation. The site's archaeology, ongoing since 1994, has uncovered forts, wells, and graves, painting a vivid picture of resilience amid ruin. Shifting gears from the depths of history, let's bridge this epic to your world today. The Virginia Company's voyage teaches us that bold beginnings, even amid uncertainty, can forge extraordinary paths. Their story of venturing into the unknown mirrors our personal quests—whether starting a career, overcoming setbacks, or chasing dreams. Here's how you can harness these lessons for tangible benefits in your life, with a step-by-step plan to turn historical wisdom into modern momentum. - **Embrace Calculated Risks for Growth Opportunities:** Just as the company weighed dangers against potential riches, assess your own ventures. For instance, if contemplating a job switch, research market trends, network with industry pros, and pilot small changes like freelance gigs to test waters without full commitment. - **Build a Diverse Support Network:** The mix of gentlemen, craftsmen, and sailors highlights teamwork's power. In your life, cultivate a circle of mentors, peers, and experts—join professional groups, attend workshops, or use apps like LinkedIn to connect, ensuring varied perspectives fuel your progress. - **Prepare Thoroughly but Adapt Flexibly:** The colonists' provisions sustained them initially, but adaptation to new environments saved them. Apply this by creating detailed plans for goals (e.g., a fitness regimen with meal preps and workouts), yet remain open to pivots—like switching routines if injuries arise. - **Learn from Setbacks Without Quitting:** Starvation and disease nearly doomed Jamestown, but persistence prevailed. When facing failures, like a rejected project, analyze errors (journal root causes), seek feedback, and iterate—turning losses into stepping stones. - **Invest in Long-Term Vision Over Quick Wins:** No gold rush, but tobacco's cultivation paid off. Focus on sustainable habits: save 10% of income monthly for investments, or dedicate weekly time to skill-building courses, compounding efforts for future rewards. - **Foster Resilience Through Community and Faith:** Prayers and native alliances bolstered morale. Build emotional fortitude by practicing gratitude daily, joining support groups for challenges like weight loss, or meditating to center yourself amid chaos. - **Innovate in the Face of Adversity:** Rolfe's tobacco hybrid revolutionized the economy. Channel this by experimenting—try new productivity tools if old methods falter, or brainstorm side hustles blending your passions, like turning a hobby into an Etsy shop. Now, a practical 30-day plan to apply these insights: