Imagine a world on the brink of unimaginable power, where a handful of brilliant minds gather not in a grand laboratory or a sterile bunker, but under the creaky wooden rafters of a forgotten university squash court. It’s December 2, 1942, and outside, the chill of a Chicago winter bites at the edges of a massive canvas tent. Inside, history is about to crackle to life—not with the roar of an explosion, but with the quiet, controlled fury of atoms splitting in unison. This is the story of the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, a feat led by Enrico Fermi and his team of scientists under the shadowy umbrella of the Manhattan Project. It’s a tale of exile, ingenuity, secrecy, and sheer audacity that reshaped our understanding of energy, warfare, and the very fabric of the universe. And while the world teetered on the edge of World War II, this event whispered a promise: that human curiosity could unlock forces both terrifying and transformative.

What makes this moment so profoundly significant? In the grand tapestry of distant history, December 2, 1942, stands as the quiet ignition of the Atomic Age. It wasn’t a battle won or a treaty signed; it was a scientific breakthrough that confirmed the feasibility of nuclear fission on a sustainable scale. For the first time, humanity didn’t just observe the atom’s secrets—we commanded them. This wasn’t mere theory; it was a chain reaction sustained for nearly 30 minutes, producing enough neutrons to prove that controlled nuclear power was no longer a dream but a reality. The implications rippled outward: from the bombs that ended one war to the reactors that power cities today, from medical isotopes that save lives to the geopolitical tensions that still shadow our world. Yet, buried beneath the drama of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this humble experiment in a repurposed sports facility often fades into obscurity. Today, over 80 years later, its echoes remind us that true power lies not in destruction, but in the disciplined pursuit of the impossible. Buckle up as we dive deep into the whirlwind of personalities, politics, and physics that made this day legendary—before we turn those lessons into fuel for your own atomic ambitions.

## The Gathering Storm: Fermi’s Flight from Fascism

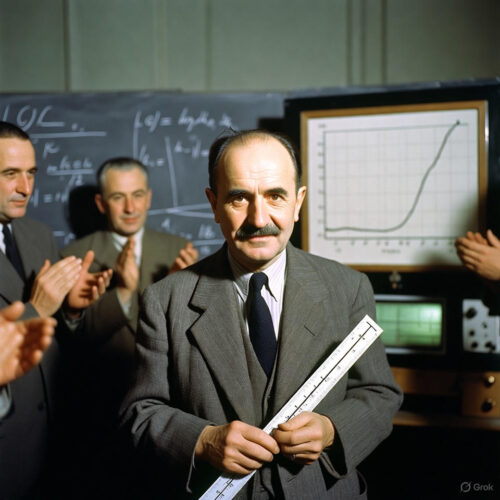

To grasp the magnitude of December 2, 1942, we must rewind to the turbulent 1930s, a decade when Europe simmered with ideological firestorms. Enrico Fermi, the linchpin of this story, was no ordinary physicist. Born in Rome in 1901 to a family of modest means—his father a railroad inspector, his mother a schoolteacher—Fermi displayed prodigious talent from childhood. By age 10, he was devouring advanced math texts; by 17, he’d published his first paper on electromagnetism. But it was in the hallowed halls of the University of Rome that Fermi truly ignited. Under the mentorship of Nobel laureate Orso Corbino, he transformed into a force of nature, blending theoretical brilliance with experimental rigor. His “Fermi statistics” revolutionized quantum mechanics, earning him the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics for work on induced radioactivity and neutron-induced reactions.

That Nobel, however, was more than an accolade—it was a lifeline. Mussolini’s Italy, gripped by fascist fervor, had enacted anti-Semitic racial laws in 1938, barring Jews from academic posts and public life. Fermi’s wife, Laura Capon, was Jewish, and though Fermi himself was not, the decree cast a long shadow over their family. Their two young children, Nella and Giulio, faced an uncertain future in a nation sliding toward alliance with Nazi Germany. Fermi, ever the pragmatist, accepted the Nobel in Stockholm on December 10, 1938, delivering a speech on subatomic particles that masked his deeper anxieties. But instead of returning home, the family boarded a Swedish liner bound for New York. Disguised as tourists to evade Italian spies, they slipped into America, where Fermi secured a professorship at Columbia University. It was a daring escape, whispered about in émigré circles, that severed ties with his homeland and thrust him into the heart of America’s nascent atomic research.

Fermi’s arrival in the U.S. coincided with a cascade of discoveries abroad. In 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann had bombarded uranium with neutrons, unwittingly splitting the atom—a process dubbed fission by Lise Meitner, the Austrian physicist exiled for her Jewish heritage. Word spread like wildfire through the scientific grapevine, alerting Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard to the peril: if Nazi Germany harnessed this power, it could build a bomb of apocalyptic scale. Their famous 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt spurred the creation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium, the seed of the Manhattan Project. By 1941, as Pearl Harbor loomed, Fermi had relocated to the University of Chicago, where he assembled a ragtag team of exiles and prodigies: Hungarian émigré Leo Szilard, the wiry theoretician who first conceived the chain reaction; Italian compatriot Enrico Persico; and a cadre of young Americans like Herbert Anderson and Walter Zinn.

These weren’t faceless lab coats; they were a motley crew bound by shared peril and passion. Szilard, with his perpetual scowl and thick accent, paced rooms debating ethics—should they even pursue the bomb? Fermi, by contrast, was the calm conductor, his pipe clenched between teeth, scribbling equations on napkins. Their debates echoed through Chicago’s gloomy winters, fueled by black coffee and the gnawing fear that across the Atlantic, Heisenberg’s team was inches away from the same breakthrough. Secrecy was paramount; the project, codenamed under the innocuous “Tube Alloys” by the British, shrouded its workings in misdirection. Fermi’s group operated under the radar, sourcing uranium oxide from Belgian Congo mines via shadowy smuggling routes, while graphite blocks—pure enough for moderators—were begged from industrial suppliers under false pretenses.

## The Pile: A Monument of Madness and Method

By mid-1942, Fermi’s vision crystallized: a “pile,” an ungainly stack of uranium-laced graphite bricks designed to slow neutrons just enough to sustain fission without runaway catastrophe. This wasn’t a sleek reactor; it was a Frankenstein’s monster of 40,000 graphite blocks, 6 tons of uranium metal, and 50 tons of uranium oxide, interwoven with cadmium control rods to tamp the reaction like a dimmer switch. The site? West Stands of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field, a derelict athletic complex slated for demolition. The squash court beneath its bleachers, with its 30-foot ceiling and concrete walls, became an improbable birthplace for atomic power. A vast tent, requisitioned from the Army Signal Corps, draped the structure to muffle radiation and prying eyes—workers joked it looked like a giant circus big top hiding a doomsday device.

Construction began in earnest that November, a Herculean labor of secrecy and sweat. Teams of “stackers”—graduate students and technicians, many in their early 20s—hauled materials through blizzard-lashed nights. Picture this: young physicist Richard Feynman, later famed for bongo drums and quantum electrodynamics, lugging 50-pound graphite cubes up rickety scaffolding, his breath fogging in the 20-degree cold. Safety was a gamble; no one fully knew the radiation risks. Geiger counters clicked ominously as they layered uranium “pseudospheres”—lumps of oxide packed into soda cans—into the lattice. Fermi oversaw every detail, his slide rule an extension of his arm, calculating critical mass with pencil scratches on yellow legal pads. “The progress is slow but steady,” he noted in a cryptic letter to his wife, Laura, who fretted at home with the children, unaware of the full scope.

Tensions mounted as deadlines loomed. The Manhattan Project’s military overseer, General Leslie Groves, barked for results from distant Washington, while rumors swirled of German advances. On November 15, the pile reached half its intended size, but tests sputtered—neutrons fled too fast, extinguished by impurities in the graphite. Fermi’s solution? Scour the blocks with carbon tetrachloride baths, a toxic slurry that left workers’ hands blistered and lungs burning. By Thanksgiving, the stack towered 20 feet high, a black ziggurat riddled with channels for control rods made from neutron-absorbing cadmium ribbons. Instruments—ionization chambers and boron trifluoride detectors—probed its innards via narrow shafts, feeding data to a makeshift control room in an adjacent hallway. The air hummed with anticipation and dread; one misplaced rod, and the pile could go supercritical, releasing a lethal burst of radiation.

Eyewitness accounts paint a scene straight from a noir thriller. The court, stripped of its squash lines, echoed with the scrape of bricks and the low murmur of Italian, Hungarian, and Midwestern accents. Floodlights cast long shadows over the pile’s jagged surface, where uranium glinted dully amid the graphite’s matte expanse. Fermi, in wool trousers and a tweed jacket, moved like a chess master, adjusting rods with the precision of a surgeon. His team included women like Leona Woods Marshall, a 23-year-old PhD who’d helped design the detectors, defying the era’s gender barriers. Black workers from the university’s maintenance crew, unwittingly integral, layered the heaviest loads, their contributions later airbrushed from official narratives—a quiet injustice in the project’s polyglot saga.

## Zero Hour: The Birth of the Atomic Flame

December 2 dawned gray and frigid, the Windy City’s gales rattling the tent flaps. Fermi’s team assembled at dawn, bleary-eyed from all-nighters, fortified by doughnuts from a nearby diner. The pile stood complete at 10:37 a.m., its 57 layers a testament to months of toil. Fermi gathered his 40-odd collaborators in the control room, a converted lounge with blackboards scrawled in chalk and a single telephone line to Arthur Compton, the project’s scientific director. “This morning,” Fermi began in his measured baritone, laced with Roman inflection, “we will attempt to achieve a self-sustaining chain reaction.” No fanfare, no speeches—just the weight of what hung in the balance.

The experiment unfolded in deliberate stages, a ballet of retraction and measurement. At 12:45 p.m., Zinn withdrew the emergency rod, a steel beam clad in cadmium, inch by inch. Meters flickered; neutron counts climbed from background whispers to insistent ticks. By 1:30 p.m., with three of five main rods pulled, the pile hovered at criticality’s edge—neutrons multiplying just shy of escape velocity. Lunch interrupted: sandwiches devoured in tense silence, Fermi sketching flux curves on a napkin. Resuming at 2:20 p.m., they edged closer. The final rod, the “zipper” that synchronized all controls, crept back under Szilard’s watchful eye. Suddenly, at 3:25 p.m., the dials surged. Neutron intensity doubled, then quadrupled, in a geometric cascade. “The reaction is going,” Fermi announced coolly, timing the exponential rise with a pocket watch. Twenty-eight minutes later, at 3:53 p.m., he ordered the rods reinserted, quenching the flame before it could overheat.

Pandemonium erupted in whispers—a bear hug from Szilard, backslaps rippling through the room. Compton, briefed by phone, dashed off a coded telegram to Washington: “The Italian navigator has landed in the New World.” No cheers echoed beyond the tent; secrecy demanded it. But inside, euphoria reigned. Radiation levels spiked to 100 milliroentgens per hour—hazardous by today’s standards—but no one keeled over. That evening, over beers at the Quadrangle Club, Fermi raised a glass: “To the pile—and to the future it unleashes.” The next day, workers dismantled the setup, scattering bricks to offsite storage, erasing traces of the miracle. Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), as it was retroactively dubbed, became a ghost, its legacy etched in declassified memos and yellowed photos.

The technical wizardry merits unpacking for its sheer elegance. Fission hinges on uranium-235’s rarity—only 0.7% of natural uranium—necessitating isotopic enrichment that CP-1 sidestepped via sheer mass. Graphite moderated neutrons, slowing them to thermal speeds ideal for absorption, while cadmium “ate” excess to prevent meltdown. The chain’s sustainability demanded a precise k-factor: multiplication constant just above 1. Fermi’s calculations, blending diffusion theory with empirical tweaks, nailed it at k=1.006—a whisper-thin margin. This wasn’t luck; it was the culmination of 1930s neutron cross-section data, smuggled from Europe amid rising tensions. Post-reaction analysis revealed 200 watts of thermal power, enough to light a few bulbs, but proof positive that scaling up could yield megawatts—or megatons.

## Ripples Through the War and Beyond: From Hanford to Hiroshima

CP-1’s success electrified the Manhattan Project, greenlighting a frenzy of scaled-up reactors. By 1943, the Hanford Site in Washington state birthed production piles churning plutonium for the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Oak Ridge, Tennessee, mastered uranium enrichment via gaseous diffusion, its Y-12 plant a labyrinth of 1940s tech wizardry. Fermi himself consulted at Los Alamos, where J. Robert Oppenheimer’s band of theorists—Richard Feynman cracking safes for fun, Edward Teller plotting hydrogen bombs—wrestled bomb design’s fiendish physics. The July 1945 Trinity test, that desert dawn’s blinding light, owed its lineage to the squash court’s quiet glow.

Yet the war’s shadow loomed ethical quandaries. Fermi, the refugee who’d fled tyranny, now armed it. Post-Hiroshima, he grappled publicly: “The fact that we made the bomb… was a moral decision.” His team scattered postwar—Szilard advocating civilian control, Woods pioneering nuclear medicine. Fermi’s 1954 death from stomach cancer, likely radiation-linked, underscored the double-edged sword. But CP-1’s progeny powered peace too: the USS Nautilus, 1954’s nuclear submarine, slicing oceans silently; Shippingport’s 1957 reactor, America’s first commercial nuke plant. By the 1960s, isotopes from such tech illuminated tumors in PET scans, saving countless lives. Globally, the IAEA’s safeguards stemmed proliferation, though shadows like Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) remind us of hubris’s cost.

Diving deeper into the personalities adds flavor. Take Szilard, the chain reaction’s conceptual father, who patented the idea in 1934 but assigned it gratis to the Navy. His paranoia—installing a personal safe for notes—stemmed from Berlin student days dodging Nazis. Or Zinn, the burly experimentalist who later helmed Argonne National Lab, quipping, “We built it with slide rules and prayers.” Women like Woods, who at 23 detected the reaction’s neutrons, shattered glass ceilings amid wartime rationing. Even the university’s role: President Robert Hutchins, a vocal critic of militarized science, reluctantly hosted the pile, later boasting, “We split the atom here—now let’s split the bill.”

The secrecy’s absurdities amuse: couriers smuggled uranium in coffee cans labeled “biscuits,” while Fermi’s coded postcards to Laura read like grocery lists—”Need more black lumps”—meaning graphite. Postwar declassification in 1950s hearings revealed anecdotes: Feynman smuggling beer into the lab via a hidden chute, or Persico’s homesick son dubbing the pile “Chicago’s newest Italian restaurant.” These human vignettes underscore a truth: amid equations and existential stakes, innovation thrives on camaraderie, the shared spark of “what if?”

## The Unsung Echoes: Lesser Lights in the Atomic Dawn

Beyond Fermi’s spotlight, December 2 spotlights overlooked threads. Consider the Belgian Congo’s uranium mines, where Congolese laborers toiled under Belgian overseers, extracting the ore that fueled CP-1. Shipped via perilous Atlantic convoys dodging U-boats, it arrived in Staten Island warehouses, a geopolitical linchpin tying African exploitation to American victory. Or the graphite saga: initial blocks from National Carbon were boron-contaminated, nearly dooming the pile. Fermi’s fix—sourcing ultrapure stock from Union Carbide—highlighted industry’s unwitting role, a footnote in supply-chain lore.

Immigration’s undercurrent fascinates too. Of CP-1’s core team, half were European exiles—Fermi (Italy), Szilard (Hungary), Wigner (Hungary), Teller (Hungary). Their flight, spurred by fascism’s rise, infused American science with unparalleled talent. The 1930s “brain drain” totaled thousands, from Einstein to von Neumann, seeding Silicon Valley’s ethos. Yet discrimination lingered: Jewish scientists faced quotas, women like Woods battled skepticism. Postwar, McCarthyism blacklisted some, like Szilard, for “subversive” anti-bomb activism.

Technically, CP-1 pioneered “exponential piles,” influencing breeder reactors that transmute waste to fuel. Its natural uranium design bypassed enrichment, inspiring Canada’s CANDU system—peaceful atoms for a Cold War world. Medical ripples? Neutron therapy, born from pile byproducts, zaps cancers today. Even cosmology benefits: Fermi’s later cosmic ray work, probing galactic accelerators, stems from atomic insights.

Fun fact: The squash court? Demolished in 1957 for a parking lot, marked by a plaque unveiled in 1966—Fermi’s bronze bust gazing skyward. Visitors still pilgrimage, pondering how a defunct gym birthed an era. Or consider the “prompt critical” debate: CP-1’s slow ramp avoided explosion, but simulations later showed a hair-trigger could have vaporized the South Side. Fermi’s margin? Millimeters on a rod.

## From Atomic Dawn to Personal Power: Harnessing the Spark Today

Now, pivot from history’s grand canvas to your daily grind. The squash court’s lesson? Controlled chain reactions aren’t just nuclear—they’re life’s blueprint. Fermi didn’t conquer the atom overnight; he stacked bricks, tested rods, iterated through failures. That disciplined curiosity, turning peril into progress, is your superpower in 2025’s chaos. Imagine channeling it: not splitting atoms, but shattering personal plateaus. The outcome—sustainable energy from chaos—mirrors building momentum in habits, careers, relationships. It’s motivational rocket fuel: if exiles in a tent could unleash infinity, what chains can you break?

Here’s how, in razor-sharp specifics:

– **Cultivate Your ‘Pile’ of Knowledge**: Fermi amassed data like graphite blocks—scour journals, podcasts, mentors for your field’s uranium. Bullet: Dedicate 20 minutes daily to one “neutron”—a micro-lesson (e.g., code snippet if programming). Track in a journal; watch exponential growth as insights chain-react into expertise, landing that promotion by Q2.

– **Embrace Exile as Edge**: Fermi’s flight honed resilience; view setbacks as emigrations to stronger shores. Bullet: When job loss hits, list three “fascist laws” (obstacles) it dodges—commute drudgery, toxic boss—and pivot: Up-skill via free Coursera nukes, networking like Szilard at émigré clubs, emerging with a freelance gig netting 30% more income.

– **Master the Control Rod**: Fermi’s rods tamed fury; you need pauses to prevent burnout. Bullet: In high-stakes projects, insert “cadmium moments”—5-minute breathers every hour. Result? Sustained creativity, like CP-1’s 28 minutes, finishing that novel draft without implosion, querying agents by spring.

– **Collaborate Like a Chain**: No solo Fermi; his team multiplied neutrons. Bullet: Build your “stack”—weekly syncs with two accountability partners (one encourager, one challenger). Share wins/fails; their feedback accelerates your reaction, turning a solo side-hustle into a $5K/month Etsy empire.

– **Ethical Calibration**: Fermi weighed bomb’s shadow; audit your ambitions’ fallout. Bullet: For every goal (e.g., career leap), map “Hiroshima risks”—does it strain family? Mitigate with boundaries, like Szilard’s advocacy, ensuring a raise boosts savings without relational fission.

– **Scale from Squash Court to Stardom**: Start small, like a tented gym; Fermi’s pile lit bulbs before cities. Bullet: Prototype micro-wins—run a 5K before marathon training. Log progress; chain them into habits yielding 10 pounds lost, confidence surging to tackle that TEDx pitch.

## Your Atomic Action Plan: Ignite in 30 Days

Ready to fission your status quo? This Fermi-forged blueprint launches you from critical mass to sustained power. Commit 30 days; track weekly in a “Pile Log.”

**Week 1: Stack the Core (Foundation Building)**

– Days 1-3: Audit your “uranium”—list top three goals (e.g., fitness peak, skill mastery, bond deepen). Source “blocks”: 10 resources each (books, apps, contacts).

– Days 4-7: Assemble—dedicate 45 minutes daily to one goal’s micro-task (e.g., 10 push-ups, code 50 lines). Insert one control rod: Evening reflection on “What chained today?”

**Week 2: Approach Criticality (Momentum Ignition)**

– Pull rods gradually: Increase tasks 20% (15 push-ups, 60 lines). Collaborate—share log with a partner for feedback.

– Midweek test: Simulate “reaction”—tackle a mini-challenge (e.g., cold email mentor). Measure neutron rise: Energy levels up? Adjust impurities (distractions) with app blockers.

**Week 3: Sustain the Chain (Optimization Loop)**

– Run at k=1.006: Full sessions, but monitor heat—cap at 90 minutes to avoid supercritical stress. Ethical check: Does this align with your “postwar” values? Tweak if needed.

– Team huddle: Virtual “control room” call; celebrate chains (e.g., streak of workouts yielding visible abs).

**Week 4: Quench and Scale (Harvest & Expand)**

– Reinsert rods: Review log, harvest wins (e.g., skill demo to boss). Dismantle/rebuilt: Archive what worked, stack anew for next goal.

– Launch: Announce one outcome publicly (LinkedIn post on milestone). Echo Fermi: “The future it unleashes” is yours—project it forward, chaining to 90-day horizons.

This isn’t theory; it’s tested physics. Fermi’s pile powered a century; yours powers you. From Chicago’s shadows to your spotlight, December 2 beckons: Control your chains, and watch worlds unfold. What’s your first brick?