In the misty annals of ancient China, where empires clashed like thunderclouds over vast rivers, one naval showdown stands out not just for its explosive drama but for its clever twist of fate. On November 26, 1161, the waters of the Yangtze River near Caishi became the stage for a battle that pitted innovation against invasion, underdogs against overlords. The Battle of Caishi wasn’t merely a skirmish; it was a pivotal moment that halted a mighty empire’s advance and showcased the power of human ingenuity. Picture this: paddle-wheel ships slicing through waves, thunderclap bombs lighting up the sky like premature fireworks, and a ragtag force turning the tide against a horde. This isn’t the stuff of legend—it’s real history, packed with intrigue, betrayal, and brilliance. And while the echoes of that day have faded over centuries, the lessons ripple forward, offering us ways to navigate our own modern battles with strategy and spark.

Let’s dive deep into the historical currents that led to this explosive encounter. The Song dynasty, ruling from 960 to 1279, was a beacon of cultural and technological splendor in China. This Han Chinese-led empire had transformed governance, art, and science, inventing everything from movable type printing to magnetic compasses. But by the 12th century, it faced existential threats from the north. The Jin dynasty, established in 1115 by the Jurchen people—a semi-nomadic group from Manchuria—had risen like a storm. Led by ambitious rulers, the Jin toppled the Liao dynasty and turned their sights southward, eyeing the fertile lands and wealth of the Song.

The roots of conflict stretched back decades. In the early 1100s, the Song and Jin had been uneasy allies against the common enemy, the Liao. The Jurchens, under their founder Wanyan Aguda, rebelled against Liao overlords in 1114-1115, founding the Jin dynasty. By 1121-1122, they joined forces with the Song to dismantle the Liao entirely. But alliances frayed quickly. Disputes over territories, particularly the strategically vital Sixteen Prefectures along the northern border, ignited hostilities. By 1125, Jin armies swept south, crossing the Yellow River and laying siege to the Song capital of Kaifeng. The assaults were brutal: in 1126 and 1127, Kaifeng fell twice, culminating in the infamous Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong and his successor Qinzong, along with thousands of royal family members and courtiers, were captured and marched north in humiliation. This catastrophe marked the end of the Northern Song and the birth of the Southern Song, as the surviving imperial prince Zhao Gou—later Emperor Gaozong—fled south and established a new capital in Hangzhou by 1129.

The Jin didn’t stop there. They installed a puppet state called Da Qi in the conquered northern territories from 1130 to 1137, using it as a buffer and proxy to drain Song resources. Jin generals like Wuzhu pushed further south, attempting to cross the Yangtze River, the natural barrier protecting the Southern Song heartland. In 1130, Wuzhu’s forces nearly captured Gaozong himself during a chaotic retreat, but Song naval commanders like Han Shizhong thwarted them with clever tactics, including blocking river passages with iron chains and fire ships. These early repulses set the tone: the Song, though weakened on land, excelled at naval warfare. By 1142, exhausted by stalemates and internal pressures, both sides signed the Treaty of Shaoxing. This accord drew the border along the Huai River, forced the Song to pay annual tributes of silver and silk, and prohibited them from buying horses from the Jin— a move to cripple Song cavalry. For nearly two decades, an uneasy peace held, but smuggling and border skirmishes simmered beneath the surface.

Enter Wanyan Liang, the man who would ignite the powder keg. In 1150, this ambitious prince orchestrated a bloody coup, assassinating his cousin Emperor Xizong and usurping the Jin throne. Styling himself as Emperor Hailingwang, Wanyan Liang was a Sinophile, fascinated by Han Chinese culture. He moved the Jin capital from the remote Huining Prefecture in Manchuria to Yanjing (modern Beijing) and planned to elevate Kaifeng as a southern capital. His policies aimed at centralizing power, adopting Han administrative systems, and promoting Confucian ideals— but at a cost. He suppressed Jurchen traditions, executed rivals, and imposed heavy taxes to fund his grand visions. By 1158, Wanyan Liang fixated on conquering the Southern Song to unify China under Jin rule. He accused the Song of violating the treaty by smuggling horses and harboring Jin deserters, using these as pretexts for war.

Preparations were massive and ruthless. Starting in 1159, Wanyan Liang drafted every able-bodied man aged 20-60 from Han Chinese households under Jin control, amassing an army claimed to number 600,000 strong, though historians like Herbert Franke estimate a more realistic 120,000 frontline troops after accounting for desertions and logistics. He stockpiled weapons, acquired 560,000 horses, and ordered the construction of a fleet in Tong Prefecture near Beijing. But haste bred flaws: many ships were shoddily built, some sinking in the Liangshan marshes during transport south. The draft sparked widespread revolts; Wanyan Liang crushed them mercilessly, executing his own stepmother, Khitan nobles, and anyone voicing dissent. A major Khitan rebellion in the northeast diverted troops, weakening his campaign before it began.

On the Song side, warning signs abounded. Diplomats noted the rudeness of Jin envoys, a deliberate insult signaling hostility. Yet Emperor Gaozong, scarred by past traumas, hesitated on full mobilization. Only in 1161 did he authorize three new garrisons along the Yangtze. Prime Minister Chen Kangbo orchestrated the defense, focusing on naval strengths. Scholar-official Yu Yunwen, originally sent to boost morale, ended up commanding ground forces at Caishi after the original general fell ill. Yu consolidated scattered units, rallying 18,000 troops and a fleet of up to 340 paddle-wheel warships—innovative vessels powered by treadmill-driven paddles for superior maneuverability.

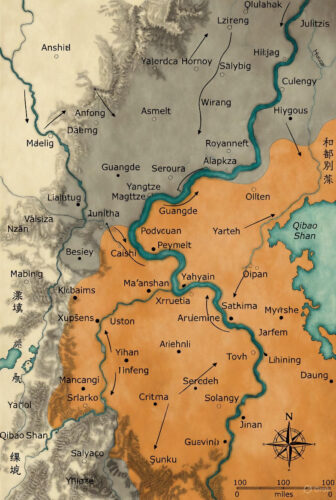

The invasion launched on October 15, 1161, when Wanyan Liang led four armies from Kaifeng. They crossed the Huai River on October 28 with little resistance, as Song defenses prioritized the Yangtze. Encamping near Yangzhou, the Jin faced supply shortages and morale dips. Desertions mounted as conscripts realized the perils of river crossing against a prepared foe. Wanyan Liang, undeterred, performed a ritual horse sacrifice on November 26, signaling the assault. His plan: ferry troops across the Yangtze at Caishi, a strategic point south of modern Nanjing near Ma’anshan, to outflank Song defenses and march on Hangzhou.

The battle erupted that day. Jin forces boarded light, double-decked ships—oarsmen below, archers and spearmen above—armored with rhinoceros hides for protection. These vessels, numbering perhaps hundreds, were makeshift, many replacements for those lost en route. As they pushed off the northern shore, Song scouts on horseback signaled from afar with flags. Hidden behind Qibao Shan island, the Song fleet ambushed from both flanks. Paddle-wheel ships, some towering with multiple decks, charged forward, their treadmills allowing speeds and turns impossible for oar-driven Jin boats.

What turned the tide were the Song’s cutting-edge weapons. Trebuchets hurled “thunderclap bombs”—incendiary devices packed with gunpowder, lime, sulfur, iron shrapnel, and possibly arsenic. These exploded on impact, releasing blinding smoke clouds that choked and burned enemies, igniting wooden hulls. Historical accounts describe the chaos: Jin soldiers, blinded and panicked, leaped into the river, drowning in droves. Song crossbowmen and infantry on the south bank repelled any who landed, led by lieutenants like Dai Gao, Jian Kang, and Shi Zhun. Yu Yunwen, from the shore, directed the fray, his presence inspiring troops who had been demoralized by rumors of Jin invincibility.

Fighting spilled into November 27. A second Jin wave met similar devastation. Wanyan Liang, watching from afar, burned his remaining ships in rage and retreated to Yangzhou. Casualties were staggering: Song sources claim 4,000 Jin dead and two commanders captured; others inflate to 24,000 slain and 500 prisoners. Conservative estimates peg Jin losses at 500 men and 20 ships, but with drownings and desertions, the toll likely exceeded 10,000. Song forces suffered minimal losses, their technological edge proving decisive.

The aftermath reshaped empires. Discontent boiled over in the Jin camp. On December 15, 1161, mutinous officers assassinated Wanyan Liang, installing his cousin as Emperor Shizong. The new ruler reversed many policies, withdrawing forces north in 1162. A 1165 treaty reaffirmed the Huai border, ending major Jin offensives. For the Song, victory boosted morale and security, allowing naval expansion from 3,000 to 52,000 sailors over the next century. Gaozong abdicated in 1162, perhaps under pressure from war critics, passing the throne to Xiaozong.

Historically, Caishi echoes the 383 AD Battle of Fei River, where a smaller force repelled invaders through cunning. It underscored the Song’s naval prowess, pioneered in the 1130s with paddle-wheels and gunpowder mandates from 1129. Innovators like Gao Xuan refined ship designs, integrating trebuchets for bomb deployment. This battle marked an early milestone in gunpowder warfare, foreshadowing its global impact. By halting Jin expansion, it preserved Southern Song culture, enabling advancements in poetry, painting, and philosophy amid division. The Jin, humbled, shifted focus inward, eventually falling to Mongols in 1234, while the Song endured until 1279.

But beyond the clash of steel and fire, Caishi’s legacy is a testament to resilience. The Song, outnumbered and outmaneuvered on land, triumphed through preparation, innovation, and unity. Wanyan Liang’s hubris—rushing ill-prepared forces—contrasted with Yu Yunwen’s adaptability, turning a morale visit into command mastery.

Now, fast-forward to today. In our fast-paced world of challenges, from career pivots to personal hurdles, Caishi’s outcome offers potent inspiration. The Song’s victory teaches that clever strategy and tools can overcome odds, a principle applicable to everyday life. Here’s how you can harness this historical fact for personal benefit:

– **Embrace Innovation in Problem-Solving**: Just as the Song deployed thunderclap bombs, seek cutting-edge tools in your field. For instance, if facing a work deadline, adopt AI software or apps like Trello for task management, turning potential chaos into streamlined success.

– **Build Resilience Through Preparation**: The Song’s hidden fleet ambushed the Jin—prepare for life’s ambushes by maintaining an emergency fund or skill-building via online courses on platforms like Coursera, ensuring you’re ready when opportunities or crises strike.

– **Foster Unity in Teams**: Yu Yunwen rallied disparate units; in your life, cultivate networks through LinkedIn or local groups, collaborating on projects to amplify individual efforts.

– **Adapt to Adversity**: When plans falter like Jin ships, pivot quickly— if a job loss hits, update your resume and network immediately, transforming setback into growth.

– **Leverage Technology for Advantage**: Mirror Song paddle-wheels by using fitness trackers or meditation apps to enhance health, outpacing personal limitations.

To apply these systematically, follow this 7-day plan:

- **Day 1: Research and Reflect** – Read about a modern innovation in your interest area (e.g., via TED Talks) and journal how it parallels Song tech.

- **Day 2: Assess Challenges** – List current obstacles and brainstorm tools or strategies to address them, inspired by Song tactics.

- **Day 3: Build Skills** – Dedicate time to learning a new app or skill, practicing adaptability.

- **Day 4: Network and Unite** – Reach out to one contact for advice, fostering unity.

- **Day 5: Prepare Proactively** – Set up a small “defense” like a backup plan for a key goal.

- **Day 6: Innovate Practically** – Apply a new tool to a daily task and note improvements.

- **Day 7: Review and Motivate** – Evaluate progress, celebrate wins, and commit to ongoing application.

Caishi reminds us: history isn’t dusty—it’s dynamite. By channeling its spirit, you can turn underdog moments into victories, proving that with wit and will, even rivers can be conquered.