Research suggests that on November 20, 1695, Zumbi dos Palmares, the legendary leader of Brazil’s largest fugitive slave community, was executed by Portuguese colonial forces, marking the end of a prolonged resistance against oppression. This event symbolizes the fierce struggle for freedom amid colonial slavery, though accounts vary on details like his exact capture. It seems likely that Zumbi’s legacy inspires modern movements for justice, highlighting themes of leadership and perseverance. Evidence leans toward viewing his story as a reminder that individual acts of courage can challenge systemic injustices, even if outcomes are complex and debated among historians.

**Key Insights from Zumbi’s Legacy**

– Zumbi, born around 1655, escaped slavery and rose to lead Quilombo dos Palmares, a self-sustaining community of escaped enslaved people that defied Portuguese rule for decades.

– His execution on this date followed the destruction of Palmares, but his resistance continues to represent Afro-Brazilian pride and anti-colonial struggle.

– Today, November 20 is celebrated as Black Awareness Day in Brazil, underscoring ongoing conversations about racial equity and historical memory.

**The Historical Context**

In the 17th century, Brazil’s colonial landscape was dominated by Portuguese plantations reliant on enslaved African labor. Quilombos like Palmares emerged as beacons of autonomy, blending African traditions with local adaptations. Zumbi’s leadership emphasized military strategy and community building, fending off multiple invasions. His refusal of peace terms that didn’t guarantee full freedom for all Africans illustrates a commitment to collective liberation.

**Modern Applications**

Applying Zumbi’s story to daily life encourages building personal “quilombos” – safe spaces of resilience amid challenges. It invites reflection on how standing firm in principles can foster growth, though success isn’t always immediate.

**Benefits for Individuals Today**

– **Cultivating Inner Strength**: Like Zumbi’s escape at age 15, identifying personal “enslavements” such as toxic habits and breaking free can lead to empowerment.

– **Community Building**: Drawing from Palmares’ hybrid society, fostering diverse support networks enhances problem-solving and emotional support.

– **Strategic Perseverance**: Zumbi’s defensive tactics remind us to plan ahead in facing obstacles, turning setbacks into opportunities for growth.

**A Practical Plan**

- Reflect weekly on one limiting belief, journaling steps to challenge it, inspired by Zumbi’s defiance.

- Build a “personal quilombo” by connecting with three supportive people monthly, sharing goals openly.

- Set resilient goals: Break a big challenge into defensive “battles,” celebrating small wins to maintain motivation.

- Study history monthly, applying one lesson from figures like Zumbi to current decisions.

- Practice daily affirmations of freedom, visualizing overcoming barriers like Zumbi did in the forests.

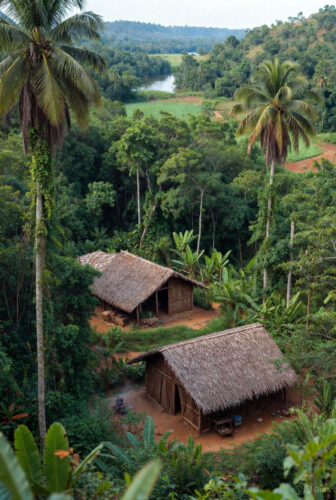

In the dense, palm-fringed hills of what is now Alagoas state in northeastern Brazil, a remarkable chapter of resistance unfolded during the height of Portuguese colonial expansion. The story centers on Zumbi dos Palmares, a figure whose life and death on November 20, 1695, encapsulate the brutal realities of transatlantic slavery and the unyielding human spirit seeking liberty. To fully appreciate this event, we must delve deep into the historical tapestry of colonial Brazil, the rise of quilombos as defiant communities, the intricate society of Palmares, the relentless conflicts with colonial powers, and the dramatic culmination that led to Zumbi’s execution. This exploration reveals not just a tale of defiance but a multifaceted saga of cultural fusion, military ingenuity, and socio-political innovation in the face of overwhelming odds.

The roots of this story trace back to the early 16th century when Portugal established its foothold in Brazil following Pedro Álvares Cabral’s arrival in 1500. By the mid-1500s, the demand for labor in sugar plantations – the economic engine of the colony – led to the massive importation of enslaved Africans, primarily from regions like Angola, the Kingdom of Kongo, and other parts of Central and West Africa. Between 1501 and 1866, Brazil received an estimated 4.9 million enslaved Africans, more than any other destination in the Americas, creating a society where enslaved people outnumbered free inhabitants in many areas. This influx brought diverse cultures, languages, and skills, but also sowed the seeds of resistance. Enslaved individuals, facing unimaginable brutality – whippings, family separations, and grueling labor – frequently escaped into the interior, forming mocambos or quilombos, terms derived from Bantu languages meaning “war camp” or “hideout.”

Quilombo dos Palmares emerged as the most formidable of these communities. Founded around 1605 by a group of about 40 escaped enslaved Africans in the Serra da Barriga region, it grew exponentially amid the chaos of the Dutch-Portuguese wars (1630-1654). During this period, the Dutch invasion of Pernambuco disrupted Portuguese control, allowing thousands of enslaved people to flee. Palmares, named for the abundant palm trees that provided food, shelter, and camouflage, expanded into a confederation of up to 11 villages, or mocambos, spanning an area comparable to modern Portugal. At its zenith in the 1670s, it housed between 20,000 to 30,000 inhabitants, including escaped Africans, Indigenous peoples, mixed-race individuals (cafuzos and mulatos), and even some marginalized Europeans who sought refuge from colonial society.

The society’s structure was a sophisticated blend of African traditions and pragmatic adaptations. Modeled after Central African kingdoms, particularly the Kingdom of Kongo, Palmares operated as a monarchy with an elected king who oversaw a council of leaders. Land was allocated by the king, and family ties played a key role in governance. Economically, the community was self-sufficient: residents cultivated crops like manioc, corn, beans, and sugarcane; raised livestock; fished and hunted in the surrounding forests; and engaged in craftsmanship, producing pottery, tools, and weapons. Trade with nearby Portuguese settlements was common, exchanging surplus goods for firearms, salt, and metal – a risky but necessary interaction that highlighted their strategic acumen. Socially, Palmares was a melting pot: Bantu languages dominated, but Portuguese was used for external dealings. Religious practices fused African animism, Catholicism (introduced via enslaved converts), and Indigenous beliefs, with rituals honoring Orixás (Yoruba deities) and possibly elements of Islam or Judaism from diverse arrivals.

Women held significant roles, often as warriors, farmers, and leaders. Figures like Dandara, Zumbi’s wife, are legendary for their combat prowess and strategic input. The community enforced strict laws, including punishments for adultery or theft, and maintained a class system where newly captured individuals from raids might be enslaved internally – a controversial aspect that mirrored the hierarchies they fled but adapted for survival. Defense was paramount: Palmares’ location in rugged, forested terrain provided natural fortifications, supplemented by wooden palisades, traps, and guerrilla tactics. Warriors, trained in capoeira-like martial arts blending African dances with combat, conducted raids on plantations to liberate more people and acquire resources, perpetuating a cycle of growth and confrontation.

Into this world was born Francisco, later known as Zumbi (meaning “warrior” or “ghost” in Kimbundu). Around 1655, in the heart of Palmares, he entered a life marked by destiny. Legends suggest his mother, Sabina, was sister to Ganga Zumba, Palmares’ earlier leader, and possibly linked to Princess Aqualtune of Kongo, who led a rebellion before her enslavement. Captured as an infant during a raid, Zumbi was taken to a Portuguese plantation in Porto Calvo, where he was baptized and educated by Father António Melo. Learning Portuguese, Latin, and Catholic sacraments, the young boy demonstrated remarkable intelligence, even constructing a model of a Kongo kingdom. But freedom called: at age 15, in 1670, he escaped back to Palmares, shedding his slave name for Zumbi.

His return coincided with escalating tensions. By 1675, Zumbi had risen to commander-in-chief of Palmares’ forces, earning renown for his physical strength, tactical brilliance, and unyielding spirit. Contemporaries viewed him as divinely inspired, possessed by Ogum, the Yoruba god of war, or a demigod immune to bullets – myths that bolstered morale. When Ganga Zumba, seeking peace after devastating attacks, signed a 1678 treaty with Governor Pedro de Almeida offering freedom for Palmares-born residents in exchange for submission and returning future escapees, Zumbi vehemently opposed it. He argued it betrayed those still enslaved elsewhere and distrusted Portuguese promises. Tensions culminated in Ganga Zumba’s mysterious death around 1680 – some accounts suggest poisoning by Zumbi’s faction – paving the way for Zumbi’s ascension as king.

Under Zumbi’s rule (1680-1695), Palmares entered its most defiant phase. He reorganized defenses, intensified raids, and fostered alliances with Indigenous groups. The Portuguese, viewing Palmares as a threat to their economic order – it inspired other escapes and drained labor – launched repeated expeditions. Between 1680 and 1686, six major assaults failed, costing lives and fortunes. One notable 1685 attack by Captain Fernão Carrilho was repelled with heavy colonial losses, thanks to Zumbi’s ambush strategies. These victories solidified Palmares’ reputation as an impregnable bastion, but pressure mounted.

The turning point came in 1694. Governor Caetano de Melo de Castro enlisted bandeirantes – rugged frontiersmen like Domingos Jorge Velho, a seasoned Paulista explorer, and Bernardo Vieira de Melo – to lead a massive force of over 3,000, including Portuguese soldiers, Indigenous allies, and artillery. After a grueling march, they besieged Cerca do Macaco, Palmares’ central fortified village, on January 14. The 42-day siege was brutal: colonists bombarded the palisades with cannons, while defenders rained arrows, boiling oil, and guerrilla strikes. Food shortages and desertions plagued both sides, but on February 6, the walls fell. In the chaos, hundreds of quilombolas died fighting; many, including women and children, chose suicide over recapture, jumping from cliffs in a tragic act of ultimate defiance.

Zumbi, wounded but alive, escaped with a small group, continuing hit-and-run resistance for nearly two years. Betrayed by a companion named Antônio Soares – possibly under torture or for reward – Zumbi was ambushed at Serra Dois Irmãos on November 20, 1695. Shot twice, he fought fiercely before being captured. To crush the myth of his immortality, his body was mutilated: castrated, decapitated, and his head sent to Recife, where it was displayed on a pike in the public square. This gruesome act aimed to deter further rebellion, but instead immortalized Zumbi as a martyr.

The fall of Palmares marked the end of the largest organized resistance to slavery in the Americas at that time, but smaller quilombos persisted until the 19th century. Its legacy influenced abolitionist movements and shaped Brazilian identity. In the 20th century, during the Black Consciousness movement, Zumbi was elevated as a national hero; since 1978, November 20 has been Black Awareness Day, with statues, festivals, and capoeira celebrations honoring him. Historians debate aspects like internal slavery or Ganga Zumba’s death, but consensus holds Palmares as a testament to African agency in the New World.

Delving deeper into the societal intricacies of Palmares reveals a microcosm of cultural resilience. The community’s governance drew heavily from Angolan models, with the king (nganga a nzumbi in Kimbundu) holding executive power but consulting a council of elders from various mocambos. Justice was swift: trials involved witnesses and oracles, with penalties ranging from fines to execution for treason. Economically, communal labor on farms ensured food security, while specialized artisans forged iron tools from scavenged materials. Trade routes connected Palmares to coastal towns, where agents bartered palm oil, honey, and hides for European goods – a delicate balance that sometimes led to alliances with sympathetic settlers.

Military organization was equally impressive. Zumbi’s forces, numbering thousands, employed hit-and-run tactics inspired by African warfare, using the terrain for ambushes. Weapons included machetes, bows, spears, and captured muskets; training emphasized agility and camouflage. Women warriors, like Aqualtune’s alleged daughters, fought alongside men, challenging gender norms of the era. Religiously, syncretism prevailed: Catholic crosses coexisted with African altars, and rituals invoked ancestors for protection. This fusion helped maintain morale during sieges.

The conflicts weren’t isolated; they intertwined with broader colonial dynamics. The Dutch, during their 1630-1654 occupation, attempted to destroy Palmares to secure labor but failed, losing expeditions in 1644-1645. After their expulsion, Portuguese captains-general like João Fernandes Vieira prioritized its eradication, offering bounties for captured fugitives. The 1677 attack under Fernão Carrilho devastated several villages, prompting Ganga Zumba’s peace overtures – a decision that split the community along ideological lines.

Zumbi’s opposition stemmed from principled radicalism. He envisioned total emancipation, not conditional freedom. His leadership style – charismatic yet authoritarian – inspired loyalty but also internal dissent. Post-1694, as a fugitive, he orchestrated raids that kept colonial forces on edge, demonstrating that Palmares’ spirit endured beyond its physical destruction.

To contextualize the final assault, consider the bandeirantes’ role. These Paulista adventurers, often of mixed Portuguese-Indigenous descent, were motivated by land grants and slave captures. Domingos Jorge Velho, a veteran of Indigenous wars, brought ruthless efficiency, employing Tupi allies skilled in tracking. The siege of Cerca do Macaco involved innovative tactics: colonists built a counter-fortification, “the trench,” to encircle the village, cutting off supplies. Defenders countered with sorties, but artillery proved decisive. Accounts describe the final breach as apocalyptic, with fires raging and screams echoing through the hills.

Zumbi’s evasion showcased his cunning: hiding in remote caves, he relied on loyalists for food. The betrayal by Soares, a former comrade captured and coerced, highlights the human frailties in resistance movements. Zumbi’s last stand – fighting despite wounds – embodied the quilombolas’ motto of liberty or death.

Post-execution, the Portuguese dismantled remaining mocambos, granting lands to victors to prevent resurgence. Yet, Palmares inspired later uprisings, like the 1835 Malê Revolt in Bahia. In modern Brazil, archaeological digs at Serra da Barriga uncover artifacts – pottery shards, iron tools – corroborating historical accounts.

**Timeline of Key Events in Quilombo dos Palmares History**

| Year | Event |

|——|——-|

| 1605 | Founding of Palmares by escaped enslaved Africans in Serra da Barriga. |

| 1630-1654 | Dutch-Portuguese wars facilitate growth as thousands flee plantations. |

| 1670 | Zumbi escapes back to Palmares at age 15. |

| 1675 | Zumbi becomes commander-in-chief. |

| 1678 | Ganga Zumba signs controversial peace treaty; Zumbi opposes. |

| 1680 | Zumbi assumes full leadership after Ganga Zumba’s death. |

| 1680-1686 | Six failed Portuguese expeditions against Palmares. |

| 1694 | Major siege and destruction of Cerca do Macaco on February 6. |

| 1695 | Zumbi captured and executed on November 20. |

This table illustrates the protracted nature of the conflict, spanning generations.

Expanding on cultural impacts, Palmares contributed to Brazilian folklore and arts. Capoeira, with its acrobatic moves disguising combat training, traces roots to quilombo warriors. Music and dances in samba and candomblé echo African rhythms preserved there. Literature, like Mario de Andrade’s “Macunaíma,” draws from its myths.

Historiographical debates add layers: early Portuguese chroniclers portrayed quilombolas as bandits, while 20th-century scholars like Edison Carneiro reframed them as proto-republicans. Recent studies emphasize gender roles and economic autonomy, using oral histories from Afro-Brazilian communities.

Transitioning to contemporary relevance, Zumbi’s story offers profound lessons without oversimplifying history’s complexities. In a world grappling with inequality, his defiance motivates personal empowerment. Benefits include fostering resilience: by emulating his strategic planning, individuals can navigate career setbacks or personal crises. Specific bullet points expand on this:

– **Embrace Adaptability**: Zumbi’s fusion of cultures teaches blending diverse influences in problem-solving, like learning new skills to pivot careers.

– **Build Defensive Networks**: Just as Palmares used terrain, create “fortifications” in life – emergency funds or mentorships – to weather storms.

– **Champion Collective Good**: His rejection of partial freedom encourages advocating for others, such as volunteering in community causes.

– **Sustain Long-Term Vision**: Enduring 15 years of leadership amid sieges inspires persistence in goals, like fitness regimes or education.

– **Honor Heritage**: Connecting to roots, as Zumbi did with African traditions, boosts self-esteem and cultural pride.

The plan outlined earlier provides a step-by-step framework: weekly reflections, monthly connections, goal breakdowns, historical study, and daily affirmations. Implementing this can transform historical knowledge into actionable motivation, turning past echoes into present triumphs.

In conclusion, Zumbi’s execution on November 20, 1695, closed a chapter but opened enduring dialogues on freedom. His story, rich in historical depth, fun in its tales of ingenuity, and motivational in its call to action, reminds us that history isn’t distant – it’s a toolkit for today.