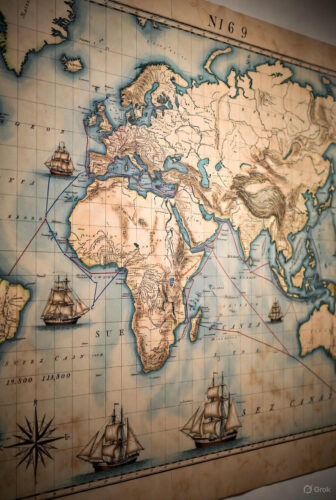

Imagine a world where continents are divided by vast oceans, and journeys that once took months are suddenly slashed to weeks. On November 17, 1869, that vision became reality with the opening of the Suez Canal, a monumental engineering feat that linked the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, forever altering the course of global trade, exploration, and human ambition. This wasn’t just a ditch dug through the Egyptian desert; it was a testament to human ingenuity, perseverance against overwhelming odds, and the power of visionary leadership. As we dive into this captivating chapter of history, we’ll explore the ancient roots, the grueling construction, the lavish inauguration, and the ripple effects that continue to shape our world. But beyond the facts, we’ll uncover how this event’s lessons can inspire you to carve your own “canals” through life’s barriers, creating shortcuts to success and fulfillment. Get ready for a journey that’s equal parts epic history and empowering motivation!

The story of the Suez Canal didn’t begin in the 19th century; its origins stretch back thousands of years to the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. As early as the 19th century BCE, during the reign of Senusret III of the Twelfth Dynasty, Egyptians attempted to connect the Nile River to the Red Sea via a canal through the Wadi Tumilat valley. This early waterway, navigable only during the Nile’s flood season, allowed for easier transport of goods and military expeditions. Historical accounts, including those from Greek philosopher Aristotle, suggest that earlier rulers like Sesostris (possibly Senusret II) contemplated such a project but abandoned it due to fears of differing sea levels causing catastrophic flooding. By the 6th century BCE, Pharaoh Necho II took up the challenge, reportedly employing 120,000 workers to dig a canal from Bubastis on the Nile to the Red Sea. Tragically, an oracle warned him that his efforts would benefit foreign invaders, leading him to halt the project after massive loss of life—though modern historians debate the accuracy of these numbers, seeing them as exaggerated for dramatic effect.

The Persian conqueror Darius I completed Necho’s canal around 522–486 BCE, creating a navigable path wide enough for two triremes to pass abreast. Inscribed stelae along the route proclaimed Darius’s achievement in multiple languages, boasting of how the canal facilitated trade from Egypt to Persia. Under the Ptolemies, Ptolemy II Philadelphus reopened and improved it in the 3rd century BCE, adding a lock system to manage water flow and prevent saltwater intrusion into the Nile’s fertile delta. This “Canal of the Pharaohs” thrived for centuries, aiding Roman Emperor Trajan in the 1st century CE when he restored it as the Amnis Traianus. However, by the Islamic era, the canal fell into disrepair. Caliph Al-Mansur ordered it closed in 767 CE to prevent enemy access, though brief revivals occurred under figures like Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah around 1000 CE. These ancient efforts highlight humanity’s long-standing dream of bridging East and West, a dream thwarted by silt, politics, and nature until the modern age.

Fast-forward to the 19th century, when European imperialism and industrial innovation reignited the idea. The catalyst was Ferdinand de Lesseps, a charismatic French diplomat born in 1805, who had served in Egypt and formed a close bond with Said Pasha, the Ottoman viceroy. De Lesseps wasn’t an engineer but a visionary networker. In 1854, he secured a concession from Said to build a canal across the Isthmus of Suez, a 120-mile strip of desert separating the two seas. To legitimize the project, de Lesseps assembled the International Commission for the Piercing of the Isthmus of Suez in 1855, gathering 13 experts from seven countries, including Austrian engineer Alois Negrelli and Belgian Louis Maurice Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds. After extensive surveys, the commission confirmed no significant elevation difference between the seas, recommending a lockless, sea-level canal based on Negrelli’s designs.

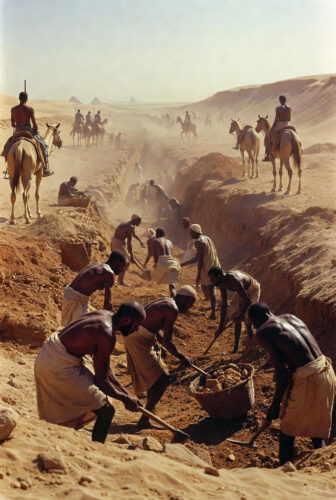

The Suez Canal Company was founded on December 15, 1858, with de Lesseps as its driving force. Raising funds proved tricky; Britain, fearing a threat to its Cape of Good Hope route and Indian trade monopoly, opposed the project vehemently. Lord Palmerston dismissed it as impractical, citing sandy terrain and labor issues. Despite this, de Lesseps sold shares primarily in France, with Egyptian backing covering 44% of the costs. Construction began on April 25, 1859, at what would become Port Said. The workforce swelled to over 1.5 million, drawn from Egypt, Europe, and beyond. Initially, forced labor (corvée) was used, with Egyptian fellahin (peasants) conscripted under harsh conditions. Britain intervened in 1864, pressuring the Ottoman Empire to abolish corvée, forcing the company to adopt mechanized dredgers and pay workers—ballooning costs to double the original 200 million francs estimate.

The construction phase was a saga of triumphs and tribulations. Workers faced scorching heat, sandstorms, and cholera outbreaks that claimed thousands of lives—official estimates put deaths at around 1,000, but some accounts inflate it to 120,000, including epidemics in 1865. Engineers grappled with excavating 97 million cubic meters of earth, using innovative steam-powered dredgers designed by French firms like Borel, Lavalley, and Couvreux. These machines, resembling floating factories, scooped sand and dumped it via conveyor belts. To supply fresh water, a parallel Sweet Water Canal was dug from the Nile to Ismailia by 1863, not only aiding workers but irrigating the arid region. Company towns sprang up: Port Said in the north, named after Said Pasha; Ismailia in the middle, honoring his successor Khedive Ismail; and Port Tewfik (now Suez) in the south. Fun fact: Ismailia was planned as a “garden city” with tree-lined streets, a stark contrast to the surrounding desert, and it hosted lavish parties to boost morale.

Challenges abounded. The Bitter Lakes, a series of hypersaline depressions, posed ecological hurdles; engineers flooded them gradually to dilute salinity, inadvertently creating a pathway for marine species migration—known today as Lessepsian migration, where over 300 Red Sea species have invaded the Mediterranean, altering ecosystems. Political intrigue added tension; Britain spread rumors of failure, and financial scandals nearly bankrupted the company. Yet, de Lesseps’s charisma prevailed. He motivated workers with bonuses and cultural events, even organizing camel races and theatrical performances in the desert camps. By 1869, the canal measured 164 kilometers long, 8 meters deep, and 22 meters wide at the bottom, with passing bays in the Ballah Bypass and Great Bitter Lake. The total cost? A staggering 432 million francs, funded by international investors who saw the potential for revolutionizing trade.

The pinnacle arrived on November 17, 1869, with the canal’s official opening—a spectacle of opulence and international diplomacy. Festivities kicked off two days earlier at Port Said, where illuminations lit the night sky, fireworks exploded in vibrant colors, and a banquet was held aboard Khedive Ismail’s yacht. Over 6,000 guests attended, including Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, Empress Eugénie of France aboard the imperial yacht L’Aigle, Crown Prince Frederick of Prussia, and Prince Henry of the Netherlands. The ceremony blended cultures: Muslim imams and Christian priests offered blessings at temporary altars on the beach, symbolizing unity. At dawn on the 17th, L’Aigle led a procession of 68 vessels into the canal, its decks adorned with flags and flowers. A minor hiccup occurred when the French ship Péluse grounded in Lake Timsah, but quick towing cleared the way.

The fleet sailed southward, stopping at Ismailia for more revelry: military parades, a grand ball in a purpose-built palace, and an opera performance of Verdi’s Aida (commissioned for the event but premiered later). Anecdotes from the day add flavor; HMS Newport, under Captain George Nares, cheekily maneuvered to be the second ship through, earning British newspapers’ praise as a “plucky little vessel” surveying for the Admiralty. The procession reached Suez by November 20, where more feasts awaited. De Lesseps telegraphed triumphs to world leaders, declaring, “The canal is open!” The event cost Egypt 1 million pounds, nearly bankrupting the khedive, but it showcased the canal as a bridge between civilizations. Newspapers worldwide hailed it as the “eighth wonder,” with The Times of London reluctantly admitting its success despite prior skepticism.

In the immediate aftermath, the canal transformed maritime routes. Before Suez, ships from Europe to Asia rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, a 19,800-kilometer trek from London to Mumbai. The canal shortened it to 11,600 kilometers, saving weeks and reducing fuel costs. In its first year, 486 ships transited, carrying 436,609 tons of cargo—modest, but traffic exploded to over 3,000 vessels by 1880. It accelerated European colonization of Africa, as powers like Britain and France gained faster access to colonies. Economically, Mediterranean ports like Trieste boomed, while Cape Town suffered. Politically, Egypt’s debt from construction led Ismail to sell his shares to Britain in 1875 for £4 million, giving Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli a strategic foothold. This move foreshadowed the 1882 British occupation after the Urabi Revolt, turning Egypt into a de facto protectorate.

The canal’s long-term significance is profound, weaving through wars, crises, and expansions. The 1888 Convention of Constantinople declared it a neutral zone open to all in peace and war, but reality differed. During World War I, it was defended against Ottoman attacks, and in World War II, Axis forces targeted it. The 1956 Suez Crisis erupted when President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the canal, prompting an Anglo-French-Israeli invasion; UN intervention reopened it in 1957. Closures followed the 1967 Six-Day War, stranding 15 ships (the “Yellow Fleet”) for eight years until 1975. Today, the canal spans 193 kilometers, deepened to 24 meters and widened to 205 meters, with a 2015 parallel channel allowing two-way traffic. It handles 12% of global trade, generating $9.4 billion in 2023 revenue for Egypt. Yet, vulnerabilities persist: the 2021 Ever Given blockage disrupted supply chains, costing billions. Environmentally, Lessepsian migration has introduced invasive species like the venomous lionfish to the Mediterranean, impacting fisheries.

Fun historical tidbits pepper this tale. De Lesseps, undeterred by critics, once quipped, “The canal will be dug by the hands of Egyptians and the money of Frenchmen.” His later Panama Canal attempt failed spectacularly due to disease and terrain, but Suez cemented his legacy. The opening inspired cultural works, from Jules Verne’s novels to modern films. Economically, it enabled the tea clipper races’ decline, as steamships dominated shorter routes. Geopolitically, it influenced the Scramble for Africa and even the Cold War, with superpowers vying for control.

Shifting from history to inspiration, the Suez Canal’s legacy offers powerful metaphors for personal growth. Just as it created a shortcut through impassable land, you can forge efficient paths in your life by overcoming obstacles with vision and persistence. Research suggests that monumental achievements like this stem from bold planning and adaptability—qualities anyone can cultivate. It seems likely that embracing such strategies leads to greater efficiency and success, though individual results vary based on circumstances. The evidence leans toward the idea that historical lessons like these foster resilience, especially in a fast-paced world.

**Key Insights from the Suez Canal for Modern Life:**

– **Vision Overcomes Doubt:** De Lesseps faced global skepticism, yet his clear goal prevailed. Today, this reminds us that big dreams often encounter resistance, but focused vision can turn naysayers into allies.

– **Perseverance Through Adversity:** Construction endured epidemics and financial woes, mirroring how personal challenges build character. Studies on resilience show that enduring hardships strengthens problem-solving skills.

– **Collaboration Breeds Success:** International experts and diverse workers united for a common purpose, highlighting how teamwork amplifies individual efforts in careers or relationships.

– **Innovation Shortens Journeys:** The canal cut travel times dramatically; similarly, adopting new tools or habits can streamline your daily routines, freeing time for passions.

– **Long-Term Impact of Bold Actions:** Its effects endure centuries later, suggesting that today’s risks can yield lifelong benefits if pursued wisely.

Now, how can you apply this to your individual life? Here’s a specific, step-by-step plan to “dig your own canal”—a motivational roadmap drawing from the event’s outcomes. This isn’t about grand engineering but creating personal shortcuts to efficiency, growth, and joy.

**Your Personal Canal-Building Plan:**

– **Step 1: Identify Your ‘Isthmus’ (1-2 Weeks):** Reflect on barriers in your life, like a time-consuming commute or inefficient work habits. Journal daily: What ‘seas’ do you want to connect—perhaps career advancement and family time? Set a specific goal, e.g., “Reduce my weekly work hours by 10 without losing productivity.”

– **Step 2: Assemble Your ‘Commission’ (2-4 Weeks):** Gather advisors—mentors, books, or apps. Research tools like time-management apps (e.g., Todoist) or courses on platforms like Coursera. Just as de Lesseps consulted experts, seek input to map your path.

– **Step 3: Break Ground with Small Actions (Ongoing, Start Immediately):** Begin ‘digging’ with daily habits. If streamlining health, walk 30 minutes daily while listening to podcasts. Track progress like workers measured earth removed—use a app to log wins.

– **Step 4: Overcome Challenges Creatively (As Needed):** When setbacks hit, adapt like introducing dredgers. If motivation wanes, gamify tasks with rewards, or join a accountability group. Remember cholera outbreaks? Build resilience with mindfulness practices.

– **Step 5: Celebrate Milestones and Expand (Every Month):** Mark progress with small ‘inaugurations’—a treat or share with friends. Once established, widen your ‘canal’ by adding layers, like networking for career shortcuts.

– **Step 6: Maintain and Adapt Long-Term (Lifetime):** Review quarterly, adjusting for changes. The canal’s expansions show sustainability requires upkeep—apply this to habits for enduring benefits.

By channeling the spirit of November 17, 1869, you’re not just learning history; you’re harnessing it to propel your life forward. The Suez Canal proves that with determination, even deserts yield to dreams. So, grab your metaphorical shovel—what shortcut will you create today?

The Suez Canal’s opening on November 17, 1869, stands as one of humanity’s greatest engineering triumphs, but its roots delve deep into antiquity, revealing a persistent human quest to conquer geography. Ancient Egyptians, under pharaohs like Senusret III around 1870 BCE, constructed rudimentary canals linking the Nile to the Red Sea via natural depressions, facilitating trade in gold, incense, and slaves. These seasonal waterways, reliant on floods, underscore early ingenuity but also limitations—siltation and maintenance proved perennial foes. Aristotle’s accounts of Sesostris’s aborted attempt due to sea-level fears illustrate early engineering myths, debunked millennia later. Necho II’s ambitious project in the 6th century BCE, chronicled by Herodotus, involved massive labor but halted amid prophetic warnings, leaving a legacy of unfinished ambition.

Darius I’s completion marked a high point, with the canal spanning from Bubastis to Suez, enabling Persian fleets to navigate swiftly. Ptolemaic enhancements added sophistication, including locks—a fun engineering precursor to modern systems. Roman restorations under Trajan emphasized military utility, transporting legions efficiently. Islamic eras saw fluctuations: Amr ibn al-As reopened it post-641 CE conquest for provisioning Medina, but strategic closures followed. Al-Mansur’s 767 CE blockade aimed to starve rebels, while Al-Hakim’s brief revival around 1000 CE highlights cyclical interest. By the Ottoman period, the idea lay dormant, buried under sand and forgotten treaties, until Napoleon’s 1799 expedition rediscovered ancient traces, sparking European fascination.

The 19th-century revival owed much to geopolitical shifts. Post-Napoleonic Europe craved faster Asian routes amid industrial booms in textiles and spices. Ferdinand de Lesseps, leveraging his consular experience in Alexandria, envisioned a neutral canal. His 1854 concession from Said Pasha granted 99-year rights, with Egypt providing land and labor. The International Commission’s 1856 report, after rigorous surveys, dismissed elevation myths, proposing a direct cut. Negrelli’s blueprints, emphasizing natural lakes, proved pivotal. Company formation in 1858 faced hurdles: British opposition, viewing it as French encroachment, delayed Ottoman ratification until 1866. Share sales targeted French bourgeoisie, with de Lesseps’s promotional tours evoking modern crowdfunding.

Construction’s scale was awe-inspiring. Starting at Port Said, workers—initially 20,000 corvée laborers—used picks, shovels, and baskets. Mechanization post-1864 introduced 60 dredgers, excavating at rates unimaginable before. Cholera epidemics in 1865 killed hundreds, prompting quarantine camps. The Sweet Water Canal, 92 kilometers long, supplied 200,000 cubic meters daily, transforming desert into oases. Towns like Ismailia, with its French-style villas and lakeside promenades, became hubs of multicultural life—Europeans, Arabs, and Africans mingling in markets. Costs escalated due to bribes, lawsuits, and redesigns; arbitration by Napoleon III in 1864 awarded Egypt compensation for ending corvée.

Key figures animated the drama. De Lesseps, dubbed “Le Grand Français,” navigated diplomacy with flair. Said Pasha’s death in 1863 shifted patronage to Ismail, who dreamed of modernizing Egypt. Engineers like Linant de Bellefonds mapped routes, while financiers like the Rothschilds underwrote bonds. Workers’ stories add humanity: Italian masons built lighthouses, Greek divers cleared rocks, and Egyptian fellahin endured backbreaking toil for meager wages. Anecdotes abound—like de Lesseps riding camels to inspect sites, or workers discovering ancient artifacts, including pharaonic obelisks repurposed for ports.

The inauguration’s extravagance rivaled royal weddings. Preparations included building a opera house in Cairo and importing European luxuries. On November 15, Port Said glowed with gas lamps, hosting banquets where caviar met baklava. The November 17 procession, with L’Aigle at the fore carrying Empress Eugénie in elegant gowns, symbolized Franco-Egyptian alliance. Blessings invoked peace: a sheikh recited Quranic verses, a priest sprinkled holy water. The fleet’s journey featured salutes from warships, with crowds lining banks waving flags. At Ismailia, 500 cooks prepared feasts for 4,000, including exotic dishes like camel stuffed with turkeys. The ball’s fireworks lit Lake Timsah, where a temporary theater staged comedies. By Suez, celebrations culminated in pyramid visits, blending ancient and modern wonders.

Immediate effects rippled globally. Trade volumes surged, with cotton from India reaching Lancashire mills faster, fueling industrial growth. Britain’s 1875 share purchase, financed by Rothschild loans, marked imperial pivot. The canal intensified African partitioning, enabling quicker troop deployments. Culturally, it inspired literature—Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days” assumed its use—and art, like Riou’s paintings of the opening.

Long-term, the canal evolved amid turmoil. Nationalization in 1956 sparked crisis, highlighting its strategic value. Expansions, like the 2015 New Suez Canal adding 35 kilometers of parallel lane, cost $8 billion, boosting capacity to 97 ships daily. Revenue funds Egypt’s economy, but risks like piracy and climate change loom. Ecologically, invasive species disrupt balances, a unintended legacy of connectivity.

Drawing parallels, the canal teaches that shortcuts require sweat but yield exponential rewards. Vision, collaboration, and adaptation—hallmarks of its success—apply to personal endeavors, from career pivots to habit reforms.