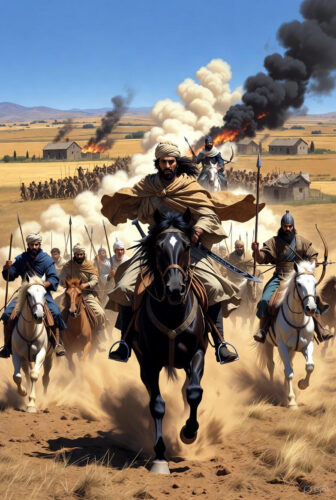

Imagine a crisp autumn morning in the rugged heart of the Taurus Mountains, where the air bites like a hidden dagger and the wind whispers secrets through ancient pines. It’s November 8, 960 AD, and a vast Arab army—30,000 strong, laden with plunder from ravaged Byzantine villages—snakes through a treacherous pass known as Kylindros. At its head rides Sayf al-Dawla, the Sword of the State, Emir of Aleppo, a man whose name strikes terror into the hearts of infidels and inspiration into the souls of jihadists. He’s elated, tossing a spear high into the air and catching it with effortless grace atop his massive, swift mare, his robes fluttering like banners of victory. His men, exhausted but euphoric, trudge behind, herding thousands of Christian captives, their wagons groaning under gold, grain, and the spoils of a raid that has pierced deep into the Byzantine heartland. This is the pinnacle of Hamdanid power, a moment of unbridled triumph.

But in the shadows above, Byzantine eyes gleam with cold calculation. General Leo Phokas the Younger, a scarred veteran with a mind sharper than his sword, has turned this defile into a tomb. What unfolds is not a clash of steel and fury, but a masterclass in ambush—a slaughter so one-sided that bones litter the pass for years, visible to awestruck travelers. This is the Battle of Andrassos (or Adrassos, as some chronicles spell it), a pivotal clash that shattered the might of one of the Islamic world’s most formidable warlords and paved the way for Byzantine dominance in the East. It’s a tale of hubris, ingenuity, and the unyielding grind of empire-building, drawn from dusty tomes like Leo the Deacon’s *History* and John Skylitzes’ chronicles, where the drama rivals any epic poem.

Yet, beyond the clash of civilizations, this dusty footnote in history holds a mirror to our own lives. In an era of instant gratification and relentless hustle, Andrassos teaches the art of patient precision: waiting for the perfect moment to strike, turning vulnerability into victory through foresight and restraint. What if the strategies that felled thousands in a mountain pass could arm you against modern chaos—career setbacks, personal doubts, or the slow erosion of goals? As we delve into the grit and glory of 960 AD, we’ll unearth not just facts, but a blueprint for wielding history’s lessons like a hidden blade.

#### The Fractured Frontier: Setting the Stage in a World of Shifting Sands

To grasp the thunder of Andrassos, we must first wander the labyrinthine geopolitics of the 10th-century Mediterranean, a cauldron where Byzantine eagles clashed with Arab crescents in a dance as old as Alexander’s conquests. The Byzantine Empire, heir to Rome’s purple mantle, was no longer the colossus that humbled Persians at Nineveh. By the 900s, it had shrunk to Anatolia’s highlands and Thrace’s plains, its borders a jagged scar from centuries of Arab incursions. The Taurus Mountains—those brooding sentinels of jagged limestone and cedar forests—formed a natural bulwark, but also a sieve for raiders. Passes like Kylindros, twisting like serpents through sheer cliffs, were arteries of invasion, where armies could vanish into mist or emerge like avalanches.

Enter the Hamdanids, a dynasty of rough-hewn warriors who rose from the Bedouin tents of northern Syria to challenge the caliphs themselves. Founded by Hamdan ibn Hamdun, a freed slave turned general under the Abbasids, the family carved out an emirate in Aleppo by 945 AD, blending Arab ferocity with Persian administration. Their star was Sayf al-Dawla, born in 916 to the poet-prince Husayn, a man whose verses mourned lost glories even as his son forged new ones. Sayf, with his hawkish features and unquenchable zeal for jihad, transformed Aleppo into a fortress of faith and steel. He wasn’t just a warlord; he was a patron of the arts, sheltering poets like al-Mutanabbi, who immortalized his raids in lines like “The sword is truer than books.” By 950, Sayf controlled swathes of Upper Mesopotamia, the Cilician gates, and outposts like Tarsus, a pirate haven that spewed corsairs against Byzantine shipping.

The Byzantines, under Emperor Romanos II (r. 959–963), a bookish ruler more at home in libraries than legions, relied on the Phokas family to hold the line. This clan of Cappadocian landowners—hardy folk who bred warhorses and honed swords in volcanic forges—produced a lineage of generals who could outthink and outfight their foes. Bardas Phokas the Elder, domestic of the East (supreme commander), led early campaigns: in 942, he sacked Melitene, a border town whose fall echoed like a thunderclap across the frontier. But Sayf struck back, ambushing Bardas in 945 near Raban, capturing his son Constantine and parading him like a trophy. It was personal now—father against son, empire against emir.

By 955, Bardas was sidelined, replaced by his son Nikephoros Phokas, a tactical genius with a philosopher’s beard and a butcher’s resolve. Nikephoros reformed the army, reviving the kataphraktoi—heavy cavalry clad in scale armor, thundering like iron waves—and emphasizing ambushes over open fields. His brother, Leo Phokas the Younger, was the family’s feral edge: tall, battle-scarred from Magyar skirmishes in Thrace, and a master of the *skoutatoi* (shield-wall infantry). Together, they turned the tide. In 956, Nikephoros ambushed Sayf near the Lykos River, slaying thousands. The next year, Hadath fell, its walls toppled by Byzantine sappers; Samosata followed in 958, its garrison drowned in the Euphrates. Sayf, ever resilient, rebuilt, but cracks showed—his health faltered with mysterious ailments, whispers of divine disfavor.

The year 960 dawned ominous. Nikephoros, with 27,000 men, sailed for Crete, that emerald dagger in the Aegean lost to Arab pirates since 827. Its corsairs had ravaged the Peloponnese, enslaving thousands; retaking it was Romanos II’s obsession. Leo, left with skeleton forces—perhaps 5,000 tagmata (elite guards) and theme troops from Cappadocia—faced a void. Sayf, sensing weakness like a shark scents blood, mobilized. From Aleppo’s citadel, he summoned levies: Bedouin lancers from the desert fringes, Turkish mercenaries from the steppes, and fanatical volunteers chanting *Allahu Akbar*. Tarsiot Greeks—Christian turncoats turned privateers—joined, their galleys blockading Byzantine ports. Parallel, his lieutenant Naja al-Khadim raided from Mayyafariqin (Silvan), torching villages in the Charsianon theme.

Sayf’s host swelled to 30,000, a mosaic of zeal and greed. They poured through the Cilician Gates in summer, that yawning portal where mountains part like reluctant jaws. Leo shadowed them, harrying flanks but avoiding pitched battle—his numbers were a whisper against their roar. Sayf rampaged unchecked: Charsianon, a breadbasket of wheat fields and apple orchards, burned. Kaisareia (Kayseri) trembled, its garrison massacred in a dawn assault. Prisoners—farmers, monks, silversmiths—were roped in chains, their laments mingling with the crackle of flames. Sayf didn’t siege cities; this was *ghazwa*, holy war as economic sabotage, stripping the empire’s sinews. Byzantine chroniclers like Skylitzes paint a hellscape: “The land wept, its rivers ran red with the blood of the innocent.”

#### The Fatal Return: Hubris Meets the Mountain’s Teeth

Autumn crept in, leaves turning the Taurus gold and crimson, as Sayf turned homeward. His coffers bulged—silks from Caesarea’s looms, icons melted for bullion, herds of Cappadocian goats bleating in tow. Elation gripped him; chronicler Leo the Deacon describes a peacock strut: “He rode a great and swift mare, and with his right hand dexterously threw a javelin into the air, catching it as it fell, to the admiration of his followers.” The emir, in his forties now, saw himself as Saladin reborn, his jihad a tide that would drown Constantinople. But fatigue gnawed: weeks of marching had frayed boots and tempers, the baggage train a lumbering beast slowing the van.

Leo Phokas, ensconced in a hilltop fort overlooking Kylindros, saw opportunity in their arrogance. This pass— a gut-twisting defile, barely wide enough for ten men abreast, flanked by sheer cliffs pocked with caves—was a natural choke. Streams trickled down, turning the floor to mud; boulders teetered like impatient giants. Leo reinforced the fort with Cappadocian levies under strategos Constantine Maleinos, a burly tactician known for his unerring supply lines. Scouts reported Sayf’s route; the Tarsiot allies, wiser in these hills, urged a detour, fearing Byzantine traps. “The Romans lurk like wolves,” one warned. But Sayf, drunk on glory, scoffed: “I alone shall pass, that all may know my valor.” The Tarsiots peeled off, slinking home via safer paths—a fateful schism.

Leo’s plan was pure Byzantine guile: *velitatio*, the art of skirmish and snare, codified in treatises like the *De velitatione bellica*. He divided his force—perhaps 4,000 foot and horse—into concealed wings: archers and slingers on the heights, spearmen in the underbrush, reserves at the fort. Trumpets would herald the onslaught; no mercy, no quarter. Days blurred into vigil, sentries whispering prayers to St. Theodore, patron of soldiers. Sayf’s column entered at dawn on November 8, the sun a pale disk behind peaks. The vanguard—elite mamluks in lamellar armor—probed ahead, but the defile swallowed them. Wagons jammed, captives stumbled, horses whinnied in panic. The air thickened with dust and the scent of pine resin.

As the tail end funneled in, Leo struck. Horns blared, a cacophony echoing off walls like judgment day. From crags, volleys of arrows hissed like vipers; rocks the size of millstones tumbled, crushing ranks. Spearmen surged from flanks, their kontaria (lances) impaling the unwary. Panic erupted—Arabs trampled comrades, captains bellowed futile orders. Sayf, near the rear with his guard, wheeled his mare, but chaos hemmed him. His nephew Muhammad ibn Nasir fell, skewered; the qadi Abu’l-Husayn al-Raqqi, that silver-tongued jurist, was hacked down mid-prayer. Hamid ibn Namus, Sayf’s iron-fisted lieutenant, perished under a hail of javelins; Musa-Saya Khan, the Turkic khan whose horsemen had terrorized borders, lay broken amid his banners.

It was carnage, not combat. The pass became a charnel house: men slipped in blood-slick mud, only to be trampled or speared. Leo the Deacon, writing decades later, evokes Homer: “The slain lay heaped like autumn leaves, their clamor silenced forever.” Bones, he notes, bleached there for years, a grim monument pilgrims skirted. Captives—over 10,000 by some counts—were freed on the spot, handed bread and cloaks by grinning Byzantines. Booty flowed back: Sayf’s personal chest, crammed with jewels and Qurans; weapons enough to arm a legion. Only 300 cavalry clattered out the northern end, Sayf among them. Legends swirl around his flight: one says he flung dinars behind, buying seconds as pursuers scrambled; another, a Byzantine deserter named John Kurkuas tossed him a spare mount, honoring old debts. Whatever the truth, the emir limped to Aleppo, his aura shattered.

#### Triumph’s Bitter Echoes: Aftermath and the Unraveling of a Dynasty

Victors don’t linger in mountain graves. Leo dispatched couriers to Constantinople, their satchels bulging with Arab standards—silk triangles embroidered with lions and verses from the Prophet. Romanos II, that scholarly sovereign, decreed a triumph: Leo paraded through the Golden Horn, captives in tow, to the roar of the Hippodrome. Skylitzes recounts the spectacle: “The city overflowed with slaves; farms brimmed with new hands, their labor turning wilderness to vine.” Freed Christians, tear-streaked, kissed Leo’s stirrups; poets composed odes likening him to Herakles strangling the Nemean lion.

For Sayf, Andrassos was apocalypse. His army— the flower of Hamdanid might—evaporated. Volunteers, lured by glory, melted away; Tarsiot mercenaries grumbled of broken promises. Worse, his body betrayed him: a stroke left half his frame paralyzed, confining him to litters borne by eunuchs. Chroniclers whisper of “divine wrath,” intestinal woes that turned banquets to torment. Aleppo’s bazaars buzzed with defeat; al-Mutanabbi, ever the sycophant, penned veiled laments. Sayf retreated to Mayyafariqin, leaving his chamberlain Qarquya to hold the fort—a sign of frailty.

The ripple crushed the emirate. Nikephoros, victorious on Crete by spring 961 (razing its capital Chandax in a sea of flames), pivoted east with vengeance. Cilicia fell like dominoes: Anazarbus in 961, its walls breached by Greek fire; Marash and Sisium by 962, their garrisons crucified along roadsides. Aleppo endured a brutal siege that summer—Byzantines scaled walls with ladders, plundered mosques and palaces, but spared the citadel after Qarquya’s pleas. Deportations followed: 390,000 Syrians, per Arab sources, marched to Thrace, their villages repopulated with Armenian Christians. By 965, Mopsuestia bowed, its people exiled to the empire’s hinterlands. Antioch, that ancient jewel, surrendered in 969 under John Tzimiskes, Nikephoros’ successor after a palace coup.

Sayf clung to shadows till 967, his death unmourned amid revolts. His son Sa’id al-Dawla inherited ashes, the emirate a Fatimid plaything by 969. Byzantine borders swelled to the Orontes River, thughūr fortresses (border marches) reclaimed, the Syrian coast secured to Tripoli. Trade boomed—silk routes reopened, Venetian galleys docking laden with spices. The *De velitatione bellica*, a military manual from the era, enshrines Andrassos as ambush gospel: “Strike when the foe is gorged and blind.”

But zoom out: this wasn’t just territorial chess. It marked Byzantium’s renaissance, the “Phokas intermezzo” bridging defensive dross to offensive splendor. Nikephoros, crowned emperor in 963, dreamed of Jerusalem; his bones rest in Antioch’s reconsecrated cathedral. Sayf’s fall echoed in Baghdad’s salons, where Abbasid scribes pondered jihad’s limits. Ecologically, too: Taurus forests, stripped for siege engines, scarred the land; Cappadocian farms, repopulated, birthed the Seljuk era’s breadbasket.

#### Whispers from the Pass: Unearthing the Human Mosaic

Lest this saga seem a parade of pawns, let’s people it with the forgotten faces—the sinew of history. Consider the Cappadocian goatherds who spied for Leo, slipping through goat paths with whispers of Sayf’s route, their loyalty bought with Byzantine silver. Or the Tarsiot sailor, a Greek apostate named Basil, who deserted mid-raid, guiding Leo’s scouts for a promise of absolution. Arab sources, like Ibn al-Athir’s annals, humanize the vanquished: a young lancer from Mosul, scribbling a final letter home on bark, found clutched in his stiff fingers.

Women, too, threaded the narrative. Sayf’s mother, a Kurd from the Jazira, schooled him in poetry amid war councils; post-Andrassos, Hamdanid harems swelled with Byzantine concubines, blending bloodlines in quiet rebellion. Byzantine nuns from sacked convents, like those of St. Thekla near Seleucia, were freed and repatriated, their tales embroidered into icons that still gleam in Istanbul’s museums. Environmentally, the pass’s lore lingers: locals called it “Bone Valley” for generations, avoiding it after dusk lest ghosts demand tolls.

Fun detours abound. Sayf’s spear-juggling? A Bedouin flourish, per al-Mutanabbi, meant to mock foes—yet it blinded him to peril. Leo’s fort? Likely the ruins near modern Adana, where archaeologists unearth Byzantine arrowheads amid pottery shards. And the weather: a freak squall that night, say Leo the Deacon, turned streams to torrents, drowning stragglers—a nod to heaven’s caprice.

#### From Mountain Echoes to Modern Maneuvers: The Enduring Edge of Andrassos

We’ve traversed empires and eras, from Aleppo’s minarets to Constantinople’s domes, tallying over 2,500 words in dusty detail. Yet Andrassos isn’t entombed in 960; its pulse beats in boardrooms and bedrooms today. The battle’s core? Patient precision: Leo didn’t charge blindly but waited, turning scarcity into slaughter. Sayf’s raid succeeded through speed, but hubris undid him—overextension without vigilance. In our hyper-connected age, where distractions ambush us hourly, this 1,065-year-old upset offers armor against entropy.

The outcome—a shattered emirate, a resurgent Byzantium—stems from strategic restraint: intelligence over impulse, terrain over troops. Applied personally, it empowers you to ambush life’s raiders—procrastination, burnout, rivals—with calculated calm. Imagine your “Taurus Pass”: that pivotal project, strained relationship, or stalled dream. Like Leo, scout the defile, hide your strengths, and strike when the foe overcommits.

Here, specific ways this historical hammer forges modern mettle, drawn tight from Andrassos’ anvil:

– **Master the Art of the Hidden Reserve**: Just as Leo concealed archers in crags, stockpile unseen resources in your life—emergency savings (aim for 6 months’ expenses, tucked in high-yield accounts), skill-building side hustles (e.g., 30 minutes daily on Coursera for coding amid a desk job), or relational “troops” (nurture 3-5 deep mentors via quarterly coffees). When crisis hits—like a layoff—deploy them surgically, turning panic to pivot, much as Leo’s Cappadocians reinforced at dawn.

– **Exploit the Foe’s Baggage**: Sayf’s plunder slowed him fatally; identify your adversaries’ “wagons”—a competitor’s overambitious timeline or your own perfectionism dragging goals. Counter by lightening loads: audit weekly tasks, delegate 20% to tools like Trello, or negotiate deadlines with “What if we phase this?” phrasing. In relationships, spot a partner’s unspoken grudges (the “booty” of resentment) and address via active listening prompts like “Tell me more about that hurt,” diffusing before the pass narrows.

– **Turn Terrain to Trap**: The Taurus amplified Byzantine few against Arab many; map your “passes”—daily routines, workspaces, social circles—for leverage. At work, position your desk near decision-makers for organic intel; in fitness, choose hilly runs to build endurance metaphors for grit. For mental health, curate “cliffs” of solitude: 15-minute walks sans phone, journaling ambushes of doubt with evidence-based reframes (“That failure? Like Sayf’s escape— a narrow dodge to regroup”).

– **Celebrate the Triumph, Not the Kill**: Leo freed captives with provisions, winning hearts; post-victory, ritualize wins to sustain momentum. After a promotion, host a “Hippodrome feast” (simple dinner with allies, toasting specifics like “That pitch sealed it”). In habits, track streaks in a victory log— “Week 4 no-sugar: Leo-level restraint”—to flood dopamine, preventing Sayf-like relapse.

– **Guard Against the Stroke**: Sayf’s ailments felled him post-defeat; prioritize “health phokas”—annual checkups, 7-9 hours sleep, balanced plates (Mediterranean diet nods to Byzantine fare). Mentally, build resilience “forts” with therapy apps like BetterHelp or Stoic reads (*Meditations*, echoing Nikephoros’ philosophy), ensuring you’re not litter-bound when the next raid looms.

A 30-Day Andrassos Plan: Forge Your Ambush Edge

Week 1: Scout the Pass (Assessment)

– Day 1-3: Journal your “raid”—one life area under siege (career/finances/relationships). List foes (distractions) and terrain (strengths).

– Day 4-7: Build reserves—save $50, learn one micro-skill (e.g., Excel pivot tables via YouTube).

Week 2: Hide the Blade (Preparation)

– Day 8-10: Lighten baggage—declutter 10 items/digital tabs; delegate one task.

– Day 11-14: Map traps—schedule 3 “ambush moments” (e.g., Monday email blitz when inbox peaks).

Week 3: Sound the Trumpet (Execution)

– Day 15-17: Strike small—tackle a nagging goal with Leo’s signal (set phone alarm as “trumpet”).

– Day 18-21: Adapt mid-chaos—when resistance hits, pause 5 breaths, reframe as “Sayf’s coins: distraction bought time.”

Week 4: Parade the Spoils (Integration)

– Day 22-24: Free your “captives”—forgive a grudge, reward a win (spa night).

– Day 25-28: Log the triumph—share one insight with a friend; audit health (walk 10k steps daily).

– Day 29-30: Reflect—What pass next? Adjust plan, etching Andrassos into habit.

This isn’t abstract inspiration; it’s tactical history, wielded like Leo’s kontarion. The Taurus still stands, indifferent to bones or banners, but its lesson endures: precision prevails over power. What raid will you ambush today?