In the annals of history, few moments capture the raw drama of human conflict quite like the Battle of Lepanto on October 7, 1571. Picture a vast armada of wooden warships slicing through the choppy waters of the Gulf of Patras, oars churning like the limbs of a colossal beast, cannons roaring in defiance of the wind. This wasn’t just a naval skirmish; it was a cataclysmic showdown between the sprawling Ottoman Empire and a fragile coalition of Christian states known as the Holy League. Fought near the strategic port of Lepanto—modern-day Naupactus in Greece—this engagement involved over 450 vessels and tens of thousands of combatants, marking the largest naval battle in the Western world since the days of ancient triremes. The clash unfolded amid the broader Ottoman–Venetian War, a theater of the endless Ottoman–Habsburg conflicts that had plagued the Mediterranean for decades. What began as a desperate bid to halt Ottoman expansion turned into a resounding victory that echoed through centuries, reshaping power dynamics and inspiring legends of heroism and divine intervention.

To understand the magnitude of Lepanto, one must delve into the turbulent backdrop of 16th-century Europe and the Islamic world. The Ottoman Empire, under sultans like the legendary Suleiman the Magnificent, had been on a relentless march of conquest since the late 1400s. By the mid-1500s, they controlled vast swaths of the Balkans, North Africa, and key islands in the eastern Mediterranean, using their formidable navy to raid Christian shipping lanes and threaten the heart of Europe. Ottoman galleys, powered by chained slaves and elite janissary soldiers, dominated the seas, turning the Mediterranean into a battleground where Christian merchants lived in perpetual fear. The empire’s expansion wasn’t merely territorial; it was ideological, clashing with the Catholic Church’s vision of Christendom during a time when Europe was already fractured by the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther’s schism had splintered the continent, making unified action against external threats a near-impossible dream.

The immediate spark for Lepanto was the Ottoman invasion of Cyprus in 1570, a prized Venetian colony rich in trade routes for spices, silks, and slaves. Sultan Selim II, who had inherited the throne in 1566 after Suleiman’s death, continued his predecessor’s aggressive policies but lacked the same military genius. Ottoman forces besieged Nicosia, the island’s capital, in July 1570, capturing it after a grueling six-week defense that cost thousands of lives. The Venetians, exhausted and outmatched, shifted their focus to Famagusta, the last major stronghold. The siege there dragged on from September 1570 into August 1571, with Ottoman commander Lala Mustafa Pasha bombarding the walls relentlessly. When the Venetian garrison finally surrendered on August 1, 1571, under promises of safe passage, Mustafa betrayed the agreement. He executed the Venetian commander, Marco Antonio Bragadin, in a horrific manner—flaying him alive and parading his stuffed skin through the streets. This atrocity sent shockwaves across Europe, fueling outrage and cries for vengeance. News of the betrayal reached Venice and Rome, where it was seen not just as a military defeat but as a profane insult to Christian honor.

Pope Pius V, a Dominican friar turned pontiff in 1566, seized on the crisis to forge the Holy League. A man of unyielding zeal, Pius V viewed the Ottoman threat as an existential danger to Catholicism, especially as Protestantism gained ground. In May 1571, he issued a papal bull calling for a crusade, pressuring reluctant powers like Spain and Venice to set aside their rivalries. Venice, reeling from Cyprus’s loss, contributed the bulk of the fleet—109 galleys and galleasses—driven by economic imperatives to protect their maritime empire. Spain, under King Philip II, provided 49 galleys, though they diverted some resources to fight Barbary pirates in North Africa. Smaller states like Genoa, the Papal States, Savoy, Tuscany, and the Knights Hospitaller joined, pooling resources in a rare display of pan-European solidarity. The League’s fleet assembled in Messina, Sicily, in late summer 1571, blessed with a banner depicting Christ crucified, carried aboard the flagship.

Command fell to John of Austria, Philip II’s illegitimate half-brother, a 24-year-old naval novice but charismatic leader appointed by the pope. John, born in 1547 as Gerónimo de Austria, had risen through Spanish ranks and symbolized Habsburg might. His deputies included the seasoned Marcantonio Colonna of the Papal States and Sebastiano Venier for Venice, though tensions simmered—Venetians resented Spanish dominance, and one pre-battle incident saw a Spanish soldier hanged for insubordination. On the Ottoman side, Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, the Kapudan Pasha (grand admiral), led from the massive galley Sultana. Ali, a skilled but overconfident commander, commanded 222 galleys and 56 galliots, crewed by 37,000 sailors and oarsmen (many Greek Christians pressed into service) and 30,000 soldiers, including fierce janissaries. His wings were led by Mehmed Sirocco, a renegade corsair on the right, and Uluç Ali, a cunning Albanian admiral on the left.

The fleets converged after the Holy League departed Messina on September 16, 1571, sailing eastward across the Ionian Sea. Scouting reports confirmed the Ottoman armada heading west from Lepanto harbor to intercept them. On October 6, the Christians anchored near the Echinades islands, debating whether to press the attack amid squalls and supply shortages. John convened a war council at dawn on October 7 aboard his flagship La Real, opting for battle despite the risks. As the sun rose, lookouts spotted the Ottoman sails. Priests administered the Sacrament, chains were struck from Christian galley slaves (who were armed and promised freedom), and trumpets blared to rally the men. The wind, initially favoring the Ottomans, shifted dramatically around noon, allowing the League to form a crescent-shaped line: left wing under Agostino Barbarigo (53 galleys, 2 galleasses), center under John (62 galleys, 2 galleasses), right under Gianandrea Doria (53 galleys, 2 galleasses), and reserve under Álvaro de Bazán (38 galleys).

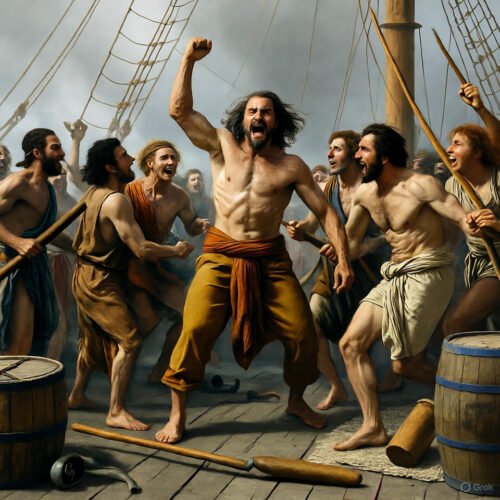

The Ottomans formed a similar line, but the Christians held a technological edge: six massive Venetian galleasses positioned ahead, armed with heavy bronze cannons that could fire devastating broadsides from afar. As the fleets closed, these floating fortresses unleashed hell—cannonballs tearing into Ottoman hulls, splintering masts, and sowing chaos in their tightly packed formation. The battle erupted in earnest around 1 p.m. On the left, Barbarigo’s wing clashed with Sirocco’s near the northern shore. Sirocco attempted an envelopment, slipping galleys between the Christians and the coast, but Barbarigo hugged the shoreline to counter it. The fighting devolved into a brutal melee, ships ramming and boarding in a floating slaughterhouse. Both commanders perished—Barbarigo from an arrow to the eye, Sirocco in the fray—while liberated Christian slaves on Ottoman vessels turned on their captors, wielding captured weapons.

In the center, the clash of flagships defined the battle’s turning point. Ali Pasha’s Sultana rammed La Real, locking the two in a deadly embrace up to the fourth rowing bench. Spanish tercios—elite pikemen and arquebusiers—poured onto the deck, clashing with janissaries in sword-and-shield combat. Muskets barked, bows twanged, and blood soaked the planks as the ships became a single battlefield. La Real teetered on the brink, but Colonna’s papal galley boarded the Sultana from the rear, capturing Ali Pasha, who was beheaded, his head impaled on a pike to demoralize the Ottomans. The Holy League banner rose over the enemy flagship, triggering a cascade of surrenders in the center. Fighting raged for two hours here, with isolated duels continuing amid smoke and screams.

On the right, Doria’s hesitation—sailing southward to avoid encirclement—opened a gap that Uluç Ali exploited, wheeling around to threaten the center and capturing the Knights Hospitaller’s flagship. Accusations of cowardice dogged Doria, but Bazán’s reserve squadron surged in, their fresh troops repelling the assault. Uluç Ali, ever the survivor, disengaged with a handful of prizes, including the Maltese banner, escaping westward. By evening, as the sun dipped, the battle wound down. Ottoman janissaries fought to the last, hurling fruit when ammunition ran dry, but mutinies among Greek rowers sealed their fate. The sea ran red with an estimated 20,000–30,000 Ottoman dead, against 7,500–10,000 Christian losses. The League captured 137 vessels, freed 15,000 slaves, and shattered the Ottoman fleet, though Uluç Ali’s survival allowed the empire to rebuild.

The outcome reverberated far beyond the gulf. Militarily, Lepanto halted Ottoman naval supremacy, preventing invasions of Sicily or Italy and securing Christian trade routes. Venice lost Cyprus permanently in 1573, but the victory bought time for Europe to consolidate. Symbolically, Pius V hailed it as a miracle, instituting the feast of Our Lady of the Victory (later Our Lady of the Rosary) on October 7, crediting rosary prayers for the win— a narrative that inspired Cervantes, who fought and lost a hand there, to pen Don Quixote. Philip II used it to bolster his Catholic credentials amid the Armada’s later failures. For the Ottomans, Selim II rebuilt the fleet within a year under Uluç Ali, but the psychological blow lingered, eroding their aura of invincibility. Long-term, it marked the twilight of galley warfare, paving the way for sail-powered navies and colonial expansions. The battle’s legacy endures in art, like Titian’s paintings, and historiography, where it’s debated as a turning point or mere respite in Ottoman decline.

Delving deeper into the human element, Lepanto was a tapestry of individual valor amid collective chaos. Take the Greek oarsmen: over 25,000 served on both sides, their resentment boiling over in mutinies that tipped scales. Venetian captains like Antonio da Canale manned ships with citizen rowers who doubled as fighters, contrasting Ottoman reliance on expendable slaves. Spanish tercios, drilled in rigid formations, outmatched janissaries in disciplined firepower—arquebuses piercing chainmail at range. The galleasses, innovations with three masts and 50 guns each, fired up to 200 rounds before contact, their crews sweating in the heat as powder smoke choked the air. Weather played a pivotal role; the noon wind shift, interpreted as divine favor, disorganized the Ottomans, whose lighter galliots floundered.

Post-battle, the victors towed prizes to safe harbors, treating wounded with rudimentary surgery—amputations without anesthesia common. Captured Turks faced enslavement or execution, mirroring Ottoman practices. News spread via couriers to Rome, where Pius V, praying the rosary, reportedly saw a vision of victory before official word arrived. Cervantes later reflected on it as a moment when “the world stood still,” capturing the battle’s mythic status.

The strategic calculus of Lepanto reveals layers of contingency. The Holy League’s artillery advantage—1,800 guns versus 750 Ottoman pieces—proved decisive, though ammo shortages nearly doomed them. Ottoman overextension, with diluted elite forces post-Suleiman, contrasted Christian motivation: crusading fervor versus imperial duty. Uluç Ali’s escape, seizing 15 galleys, underscored incomplete triumph; by 1572, the Ottomans raided Spanish coasts anew. Yet, Lepanto’s moral victory endures, symbolizing resilience against overwhelming odds.

In the centuries since, historians debate its impacts: Did it accelerate Ottoman stagnation, or was decline inevitable? It certainly boosted European confidence, influencing the Battle of Lepanto’s cultural footprint in operas, novels, and festivals. The feast day persists in Catholic liturgy, a reminder of unity forged in crisis.

The outcome of Lepanto—a coalition triumphing through shared purpose and bold action—offers profound benefits for individuals today facing personal “empires” of challenge, like career stagnation or health battles. By emulating the League’s resolve, one can harness collective strength and strategic preparation to overcome obstacles.

– Cultivate alliances: Just as Venice and Spain bridged enmities, network with diverse contacts—join professional groups or mentor programs to pool resources against workplace rivals, turning solo struggles into supported advances.

– Embrace technological edges: The galleasses’ firepower mirrors modern tools; invest in skills like AI proficiency or data analytics to disrupt competitors, gaining an “artillery” advantage in job markets or projects.

– Seize shifting winds: The battle’s wind change symbolizes opportunity; monitor personal “weather”—economic trends or health metrics—and pivot quickly, such as upskilling during downturns to emerge stronger.

– Rally inner forces: Freeing slaves parallels self-liberation; identify and “arm” suppressed talents, like turning a hobby into a side hustle, fueling motivation amid drudgery.

– Persist post-victory: Ottomans rebuilt, so maintain gains—after a promotion, continue learning to prevent backsliding, building a “reserve squadron” of habits like daily reading.

To apply this, follow this plan: Week 1: Assess your “Ottoman threat”—list top challenges and potential allies. Week 2: Build your fleet—network via LinkedIn or events, acquiring one new skill. Week 3: Engage—tackle a key issue with prepared tactics, tracking progress daily. Week 4: Reflect and reserve—celebrate wins, stockpile resources for future battles, reviewing what “winds” aided you.

Lepanto’s echoes motivate: In a divided world, unity prevails. Dive into history’s waves, and ride them to personal victory.