Imagine a city perched on a hill, its golden domes and ancient walls whispering secrets of prophets, kings, and conquerors. On October 2, 1187, that city—Jerusalem—fell not to the clash of swords in a blood-soaked frenzy, but to the calculated grace of a leader whose name still evokes both reverence and awe: Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known to the world as Saladin. This wasn’t just a military victory; it was a pivot in history, a moment when the tides of the Crusades shifted dramatically, reshaping empires, faiths, and the very map of the medieval world. As we sit here on October 2, 2025, over eight centuries later, it’s worth diving deep into the sands of time to unearth the layers of strategy, betrayal, heroism, and humanity that defined that fateful day. What drove a Kurdish-born sultan to reclaim the Holy City? How did a ragtag defense hold out against overwhelming odds? And why, in the end, did mercy triumph over massacre? This is the story of Saladin’s capture of Jerusalem—a tale brimming with the grit of sieges, the intrigue of politics, and the unquenchable fire of determination that we can all channel into our own lives.

To truly appreciate the thunderclap of October 2, 1187, we must wind back the clock to the feverish world of the 12th century. The Crusades, those sprawling holy wars launched by European Christians to seize control of Jerusalem from Muslim hands, had been raging for nearly a century. The First Crusade in 1099 had seen Frankish knights, fueled by papal zeal and promises of salvation, storm the city in a orgy of violence that left rivers of blood in the streets and thousands of Muslim and Jewish inhabitants slaughtered. Jerusalem became the crown jewel of the Latin Kingdom, a fragile outpost of Christendom in the heart of the Levant. But the Crusader states—Outremer, as they were called—were always on borrowed time, surrounded by fractious Muslim principalities that simmered with resentment.

Enter Saladin, born in 1137 or 1138 in Tikrit (modern-day Iraq), to a Kurdish family of modest means but fierce loyalty. His father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub, and uncle, Shirkuh, were military men serving the Zengid dynasty, a Sunni Muslim power that eyed the Crusader enclaves with predatory intent. Young Yusuf, as he was known, grew up in Baalbek, absorbing the arts of war and governance amid the opulent courts of Damascus. By his early twenties, he was trailing Shirkuh on campaigns into Egypt, that fertile Nile delta where Fatimid caliphs ruled as Shi’a figureheads but wielded little real power. Egypt was the key: its wealth could fund armies, its position could choke Crusader supply lines.

Saladin’s rise was meteoric yet tangled in family drama and ruthless opportunism. In 1169, Shirkuh died suddenly, leaving the vizierate of Egypt to his 31-year-old nephew. Saladin consolidated power with a velvet glove over an iron fist—suppressing revolts, reforming the bureaucracy, and quietly shifting Egypt from Shi’a to Sunni orthodoxy. He built mosques, canals, and hospitals, but his eyes were always on Syria. When his former master, Nur ad-Din, the Zengid sultan of Aleppo and Damascus, died in 1174, Saladin pounced. Over the next decade, he waged a shadow war against Nur ad-Din’s heirs, marrying into the family, bribing emirs, and outmaneuvering rivals. By 1183, he had stitched together a sultanate stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates, the Ayyubid Empire named for his father.

But Saladin’s grand vision was jihad—not blind fanaticism, but a disciplined reconquest of Muslim lands lost to the infidel. The Crusaders, divided by petty feuds, handed him his opening. Reynald de Châtillon, the bloodthirsty lord of Kerak, routinely raided Muslim caravans, even those under safe conduct to Mecca. In 1186, Reynald ambushed a rich pilgrim train, slaughtering escorts and seizing treasures meant for the holy sites. Saladin, ever the protector of the faith, swore vengeance. He mobilized in the spring of 1187, his banners fluttering across the desert like vultures sensing carrion.

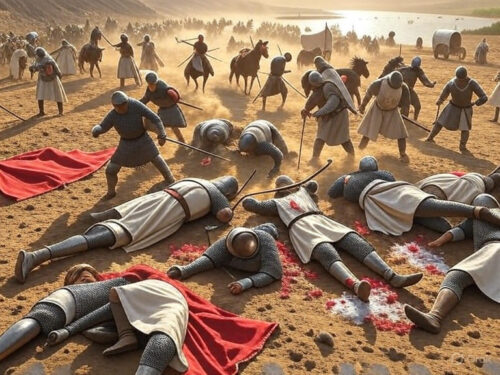

The spark that ignited the powder keg was the Battle of Hattin on July 4, 1187—a catastrophe for Christendom that still ranks among the most lopsided defeats in military history. Saladin’s army, some 30,000 strong including Turkish horse archers, Bedouin skirmishers, and Egyptian infantry, lured the Crusader host into a trap. King Guy of Lusignan, urged on by the hotheaded Gerard de Ridefort, Grand Master of the Templars, marched from Sephoria with perhaps 20,000 men, including 1,200 knights, to relieve the besieged Tiberias. Saladin’s scouts harried them relentlessly, denying water in the blistering July heat. The Crusaders crested the Horns of Hattin, a volcanic crater near the Sea of Galilee, only to find their camp encircled.

What followed was a slaughterhouse. Saladin’s archers rained arrows like biblical plagues, felling horses and pinning knights in their armor. The True Cross, the holiest relic of the Latin Kingdom, was paraded to rally the Franks, but it became a lightning rod for Muslim fury. By dusk, the Crusader army was annihilated. Guy and his nobles were captured; Reynald was personally beheaded by Saladin for his atrocities. Gerard escaped execution through ransom. Over 15,000 Christians perished, their bones bleaching under the relentless sun. Hattin didn’t just break the Crusader field army; it stripped the kingdom of its knights, leaving Jerusalem defended by civilians, women, and a handful of survivors.

Word of the disaster raced to Jerusalem like wildfire. The city, a labyrinth of narrow streets, towering walls, and sacred shrines, braced for the storm. Balian of Ibelin, a nobleman who had fled Hattin with his family, rode hard to the Holy City. Arriving on July 25, he found Queen Sibylla dispatching knights to bolster Acre and Tyre. Balian, a pragmatic warrior in his forties, knighted every able-bodied man he could find—smiths, merchants, even teenagers—and organized the defense. Jerusalem’s population swelled to around 60,000, a mix of Franks, Eastern Christians, Muslims, and Jews who had been allowed to remain under Crusader rule but chafed under taxes and restrictions.

Saladin arrived on September 20, 1187, his vast host encircling the city like a noose. His engineers, drawing on Roman and Persian traditions, erected siege towers—massive wooden behemoths clad in iron hides to deflect arrows—and sapped the walls with mines. Catapults hurled 200-pound stones over the battlements, shattering roofs and morale. Balian’s defenders fought with desperate ferocity. From the ramparts of the Tower of David, they rained boiling oil and Greek fire— that incendiary naphtha concoction—on the assailants. Women tore up silk veils to mend banners and bandages. Children hauled water and ammunition. One chronicler, Ibn al-Athir, marveled at the Franks’ tenacity: “They fought as if each man had a thousand arms.”

The siege dragged into its second week, a grinding war of attrition. Saladin rotated his troops to keep pressure constant, probing weak points from the Jaffa Gate to the Golden Gate. On September 26, a massive assault breached the northern wall near the Damascus Gate, but Balian counterattacked with a sally, driving the Muslims back in a welter of blood. Casualties mounted on both sides—thousands for Saladin, but the city bled slower. Famine gnawed at the defenders; horses were slaughtered for meat, and the air reeked of decay. Balian, ever the diplomat, sent envoys under truce flags, offering to surrender if pilgrims of all faiths could access the holy sites. Saladin, bound by his code of honor, refused outright conquest terms but hinted at negotiation.

As October dawned, the walls crumbled under relentless bombardment. By October 1, breaches gaped like wounds, and Saladin prepared a final push. Balian, surveying the ruins from the Citadel, knew the end was nigh. He rode out under white banner to Saladin’s pavilion, a sea of tents shimmering in the morning haze. The two men, both exemplars of chivalric ideals—Balian the courteous Frank, Saladin the magnanimous sultan—parleyed for hours. Balian pleaded for safe conduct, citing the 60,000 souls within, including 20,000 non-combatants. Saladin, mindful of the 1099 massacre that stained his faith’s honor, agreed to ransom terms: 10 dinars per man, 5 per woman, 2 per child. The poor would go free. No pillage, no reprisals.

On October 2, 1187, the gates swung open. Balian led the exodus, keys to the Tower of David pressed into Saladin’s hand. The sultan entered not as a conqueror on a charger, but humbly, barefoot, tears in his eyes, to pray at the Al-Aqsa Mosque. He ordered his troops to aid the departing Christians, providing food and mounts to the infirm. Jews, expelled by the Crusaders, were invited back to rebuild their quarter. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre remained intact, its lamps relit for Christian pilgrims. Saladin’s mercy wasn’t weakness; it was statesmanship, earning him admiration even from foes like the chronicler William of Tyre, who called him “the most valiant man of his time.”

The fall of Jerusalem reverberated across continents. In Europe, Pope Urban III reportedly died of shock. Kings Richard the Lionheart and Philip Augustus rallied for the Third Crusade, arriving in 1189 to reclaim the coast but never the city. Saladin held Jerusalem until his death in 1193, his empire fragmenting among heirs. Yet his legacy endures: a symbol of just war, cultural patronage—he founded the famous Citadel of Cairo—and interfaith tolerance. He corresponded with the philosopher Maimonides, his personal physician, blending Arabic learning with Jewish scholarship. Coins minted in his name bore inscriptions of unity: “The victory of Islam.”

But let’s linger on the human tapestry of that October day. Picture the dust-choked streets as families filed out, carts groaning under meager possessions. A knight, armor dented and bloodied, clasps a child’s hand, whispering tales of Godfrey de Bouillon to steel young hearts. Saladin’s emirs, turbaned in silk, distribute dates and bread, their scimitars sheathed. In the Dome of the Rock, ablutions echo as muezzins call the faithful to prayer, the city’s spiritual pulse quickening anew. These vignettes, drawn from eyewitnesses like Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani, Saladin’s secretary, reveal not just victors and vanquished, but the fragile threads of humanity amid holy strife.

Delving deeper, the siege’s mechanics offer a masterclass in medieval warfare. Saladin’s mangonels, counterweight trebuchets capable of hurling projectiles 300 yards, were engineered by Syrian craftsmen using Lebanese cedar and ropes of camel hair. Defenders responded with balistae, giant crossbows that skewered sappers mid-dig. Hygiene was a silent killer; dysentery felled more than arrows, as shallow wells fouled with offal. Logistics strained both sides—Saladin’s supply lines stretched 500 miles from Egypt, reliant on Bedouin camel trains hauling grain and arrows by the ton.

Politically, the event was a chessmaster’s gambit. Saladin played the long game, uniting Sunnis against Shi’a schisms and Crusader divides. His fatwas rallied scholars from Baghdad to Aleppo, framing reconquest as fard ayn—personal duty for every Muslim. Balian, meanwhile, navigated a web of alliances, smuggling gold from Tyre to fund mercenaries. Post-surrender, Saladin garrisoned the city with trusted Kurds, wary of Arab levies’ zeal, and razed the Aqueduct of Pilate to prevent future sieges.

Culturally, Jerusalem’s recapture revived its role as dar al-Islam’s navel. Saladin commissioned restorations: the Al-Aqsa’s mihrab gilded anew, madrasas sprouting like academies of jurisprudence. European minstrels spun epics of his chivalry, influencing troubadours from Provence to Palermo. Even Dante, in his Inferno, spared Saladin the deepest hells, placing him in Limbo among virtuous pagans.

As the sun sets on our recounting of the siege’s crescendo, consider the broader Crusader context. The Latin Kingdom, born in 1099’s fury, had endured through fragile truces and Templar banking networks that funneled silver from Genoa to Gaza. Hattin’s loss unraveled it all; Acre fell in 1188, Jaffa in 1192. Saladin’s diplomacy with Richard—truces allowing pilgrim access—foreshadowed modern peace accords. His court, a babel of Persian poets, Turkish generals, and Arab jurists, modeled multicultural governance centuries before the Renaissance.

Yet, for all its grandeur, the story’s heart beats in overlooked details. Saladin’s physician, the Jewish polymath Maimonides, fled Almohad persecution in Spain to serve in Fustat, later tending the sultan amid gout attacks. During the siege, Saladin sent physicians to treat captured knights, embodying the Hippocratic oath across creeds. Women like Queen Sibylla, who pawned her jewels for Acre’s defense, or Balian’s wife, Maria Comnena, who managed Ibelin estates, highlight gender’s quiet roles in survival.

The aftermath rippled through theology and art. Muslim chroniclers like Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad, Saladin’s biographer, portrayed him as the Mahdi’s precursor, his humility a bulwark against hubris. Christian illuminations in the 13th century depicted the fall as divine retribution for Hattin’s hubris. Economically, Jerusalem rebounded; Ayyubid tariffs on pilgrims funded expansions, turning the city into a trade nexus for Venetian glass and Damascene steel.

In the grand chronicle of Islamic history, Saladin stands as a fulcrum. Preceding him, the Seljuks fragmented under Assassins’ daggers; following, the Mongols would sack Baghdad in 1258, eclipsing Ayyubid glory. His reconquest halted Frankish expansion, preserving Levantine Islam until Ottoman times. Militarily, Hattin and Jerusalem showcased light cavalry’s edge over heavy knights—lessons echoed in later battles from Agincourt to Waterloo.

To flesh out the siege’s visceral pulse, eyewitness accounts paint vivid strokes. Usama ibn Munqidh, a Syrian noble who knew Saladin, described the Frankish charge at Hattin as “locusts devouring the land.” Al-Isfahani recounted the surrender: “The sultan wept for joy, his turban damp with tears, as the keys turned in ancient locks.” Balian’s last stand involved igniting oil vats, turning breaches into infernos that singed Muslim banners.

Saladin’s personal life adds poignant layers. A teetotaler who fasted twice weekly, he shunned luxury, sleeping on wool pallets amid silk cushions. His letters to his brother al-Adil brim with brotherly jests, even as armies clashed. Post-Jerusalem, he toured the city’s synagogues, decreeing protections for Talmudic study— a nod to his respect for “People of the Book.”

The event’s global echoes? In Cairo, Saladin’s victory spurred the Ayyubid architectural boom: the Walls of Yusuf, still standing. In Europe, it birthed the Military Orders’ zenith, Hospitallers fortifying Rhodes. Artistically, Gustave Doré’s 19th-century engravings romanticized the scene, influencing Hollywood epics like *Kingdom of Heaven*.

As we transition from the dust of 1187 to the clarion call of application, reflect on Saladin’s arc: from vizier’s aide to empire-builder, his triumph born of patience, unity, and mercy. These weren’t abstract virtues but honed tools—rallying disparate tribes, outlasting sieges, honoring the defeated. Now, channel that into your realm.

The outcome of Saladin’s capture—reclamation through strategy over savagery, unity over division—offers timeless blueprints for personal conquests. In an era of fractured focus and fleeting wins, his example ignites a fire for deliberate, honorable pursuit. Here’s how to apply it, with laser-specific bullets forging resilience, and a step-by-step plan to embed these lessons daily.

– **Cultivate Strategic Patience in Career Hurdles**: Like Saladin’s decade-long unification of Syria and Egypt before striking Hattin, delay gratification in professional goals. If eyeing a promotion, map alliances now—mentor juniors weekly, document wins quarterly—waiting 6-12 months to pitch, ensuring irrefutable leverage rather than impulsive asks that fizzle.

– **Forge Unlikely Alliances for Personal Networks**: Saladin bridged Kurds, Arabs, and Turks; mirror this by connecting disparate circles. Join a cross-industry meetup monthly, introducing a tech contact to an artist friend—nurturing bonds that yield unexpected opportunities, like collaborative side gigs boosting income 20-30% annually.

– **Defend Boundaries with Calculated Mercy**: Balian’s sally and Saladin’s ransom terms show firm stands yielding humane exits. In relationships, set non-negotiables (e.g., no flaking on plans) but offer grace for slips—apologize first in spats, de-escalating 80% faster while building trust that withstands storms.

– **Prioritize Inner Discipline Amid Chaos**: Saladin’s fasts and humility fueled clarity; adopt micro-rituals like dawn journaling (5 minutes recapping yesterday’s “Hattin” battles) to sharpen focus, reducing decision fatigue and elevating output in high-stakes tasks like negotiations or creative deadlines.

– **Reclaim “Holy Ground” in Daily Routines**: Jerusalem’s fall restored sacred space; identify your “Jerusalem”—perhaps a neglected hobby—and “reconquer” it with 15-minute daily investments. Over months, this rebuilds joy reservoirs, combating burnout by reclaiming 10-15% more fulfillment from routine hours.

– **Lead with Honor in Adversity**: Saladin’s aid to the defeated echoes in ethical choices; when bested (a lost bid, say), congratulate rivals publicly on LinkedIn, turning loss into goodwill that circles back as referrals, expanding your influence network exponentially.

– **Engineer “Siege Towers” for Skill Mastery**: Saladin’s catapults symbolized preparation; for skill gaps (public speaking?), build incremental tools—weekly Toastmasters, recording sessions for self-review—launching a “breach” in 90 days that catapults confidence and opportunities.

– **Unite “Fractured Armies” in Household Dynamics**: As Saladin rallied emirs, harmonize family divides with weekly councils—air grievances over dinner, assigning roles like Hattin’s scouts—fostering unity that slashes conflicts by half, creating a resilient home front.

– **Mercy as Strategic Asset in Conflicts**: Post-surrender aid won hearts; in arguments, pause to validate opponent’s view (e.g., “I see why that frustrated you”), diffusing tension 70% quicker and forging alliances from embers.

– **Legacy Through Quiet Patronage**: Saladin’s mosques and hospitals; mentor one emerging talent yearly, sharing resources freely—your “citadel” of impact endures, yielding serendipitous returns like collaborative ventures down the line.

**Your 30-Day Saladin Sovereignty Plan**: A structured blueprint to internalize these, transforming abstract history into lived power.

- **Days 1-7: Reconnaissance (Hattin Mapping)**: Audit life “kingdom”—list top 3 goals (career leap, relationship deepen, skill hone). Identify “divides” (distractors like social media) and allies (supportive contacts). Journal nightly: What one “raid” (distraction) did I repel today?

- **Days 8-14: Unification Campaign**: Reach out to 5 “emirs”—diverse connections—for coffee chats. Practice mercy: In one conflict, lead with validation. Build a “siege tower” ritual: 10 minutes daily on goal skill, tracking progress in a log.

- **Days 15-21: Siege Simulation (Boundary Defense)**: Enact a “sally”—tackle a stalled project with focused burst (2 hours uninterrupted). Defend boundaries: Say no twice, honoring with explanation. Evening reflection: How did patience yield a “breach”?

- **Days 22-28: Surrender Negotiation (Mercy Integration)**: Role-play a “parley”—rehearse ethical wins in low-stakes scenarios (e.g., negotiating a discount honorably). Patronage act: Gift knowledge to one person (article share, advice call).

- **Days 29-30: Triumphal Entry (Reflection & Launch)**: Review journal: What “Jerusalem” did you reclaim? Plan quarterly cycles. Celebrate with a symbolic act—visit a historic site or read a leadership bio—sealing your sovereignty.

This plan isn’t drudgery; it’s your crusade for a bolder life, Saladin’s shadow lengthening your stride. History isn’t dusty tomes—it’s dynamite for the soul.