Welcome to a journey through time, where the thundering hooves of Mongol horses echo across centuries, and the story of one man’s indomitable will reshapes empires and minds alike. On this day, August 18, in the year 1227, the world lost Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire and arguably the greatest conqueror in history. But his death was not an end—it was the culmination of a life that spanned brutal hardships, epic victories, and revolutionary innovations. In this blog, we’ll dive deep into the historical tapestry of Genghis Khan’s existence, exploring his origins, rise, conquests, and the mysterious circumstances surrounding his final moments. We’ll uncover fun anecdotes, educational insights, and the sheer scale of his impact, all while keeping the narrative lively and engaging. Then, we’ll bridge the past to the present, showing how the lessons from his life can supercharge your personal growth with practical, motivational strategies. Buckle up—this is history at its most thrilling!

#### The Origins of a Legend: Temüjin’s Turbulent Early Years

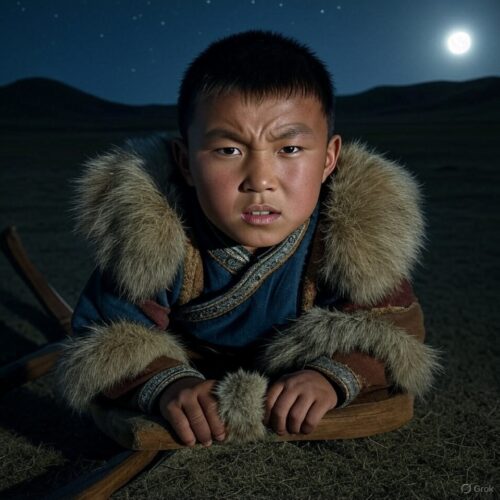

Imagine a vast, unforgiving steppe where survival is a daily battle against nature and rivals. This was the world into which Temüjin, later known as Genghis Khan, was born around 1162 near the Onon River in what is now Mongolia. His birth was shrouded in myth: legends claim he emerged clutching a blood clot in his fist, a portent of the bloodshed and glory to come. His father, Yesugei, was a chieftain of the Borjigin clan, a minor but proud group among the nomadic Mongol tribes. Yesugei named his son after a captured enemy, Temüchin-uge, perhaps to instill a warrior’s spirit from the start.

Life on the steppe was harsh. Tribes like the Mongols, Merkits, Tatars, and Naimans constantly raided each other for livestock, women, and honor. Temüjin learned to ride horses before he could walk properly, mastering archery and hunting as essential skills. At age nine, his father arranged a betrothal to Börte, a girl from the Onggirat tribe, to forge alliances. But tragedy struck when Yesugei was poisoned by Tatars during a feast. The family—Temüjin, his mother Hö’elün, siblings, and half-siblings—was abandoned by their clan, the Tayichiud, who saw no value in supporting a widow and children.

For years, they scraped by as outcasts, eating roots, fish, and whatever they could hunt. One infamous incident saw Temüjin and his brother Qasar kill their half-brother Behter in a dispute over a fish—a stark illustration of the brutal pragmatism required for survival. The Secret History of the Mongols, a 13th-century chronicle that’s like the Mongol equivalent of an epic saga, recounts how Hö’elün scolded them fiercely, emphasizing family unity. This period honed Temüjin’s cunning and charisma. He attracted loyal followers, like Bo’orchu, who joined after helping recover stolen horses, proving that even in poverty, Temüjin inspired devotion.

Captured by the Tayichiud as a teenager, Temüjin was enslaved with a wooden yoke around his neck. His daring escape, aided by a sympathetic guard named Sorkan-Shira, became a turning point. Hiding in a river overnight, he evaded pursuers and reunited with his family. This escapade not only boosted his reputation but also highlighted his resourcefulness—skills that would later turn tribes into an empire.

Fun fact: The Mongols believed in shamanism, and Temüjin’s early life was filled with omens. His mother, abducted by Yesugei from another tribe, embodied the era’s raiding culture, where women like her became pillars of strength, raising warriors amid chaos.

#### Forging Unity: The Rise to Khan of Khans

By his late teens, Temüjin married Börte, but their union was short-lived when Merkits raided and abducted her in revenge for Hö’elün’s kidnapping years earlier. Temüjin turned to Toghrul, khan of the powerful Kerait tribe and his father’s sworn brother, for help. With Toghrul and his childhood friend Jamukha, he launched a rescue, crushing the Merkits. Börte was saved, but her pregnancy with Jochi raised paternity questions, a taboo that haunted the family.

Over the next decade, Temüjin built alliances through marriages—his daughters wed to key tribes—and military prowess. He and Jamukha campaigned together, but rivalry brewed. Jamukha, elected gur-khan (universal ruler) by some tribes, represented traditional aristocracy, while Temüjin championed meritocracy, promoting based on talent, not birth.

The split came in 1187 at the Battle of Dalan Balzhat, where Jamukha defeated Temüjin, boiling 70 young captives alive in cauldrons—a gruesome act that drove defectors to Temüjin. Exiled, Temüjin may have served the Jin dynasty in China, honing tactics against settled armies. Returning in the 1190s, he aided Toghrul against threats, earning the title cha-ut kuri.

Key victories followed: subduing the Tatars (avenging his father), Jurkin, and Tayichiud. He executed rival leaders but spared and integrated common warriors, a revolutionary policy that swelled his ranks. By 1201, Jamukha rallied a coalition, but Temüjin triumphed at Köiten, capturing and executing Jamukha in 1205 after his betrayal. Jamukha’s last words, requesting death without blood spilled, underscored their tragic bond.

In 1206, at a grand kurultai by the Onon River, Temüjin was proclaimed Genghis Khan, “Oceanic Ruler.” He reorganized society: decimal army units (arban of 10, jaghun of 100, up to tumen of 10,000), a merit-based yam postal system for communication, and laws (Yassa) banning theft, adultery, and promoting religious tolerance. He adopted the Uyghur script for administration, blending nomad mobility with bureaucratic efficiency.

Interesting anecdote: Genghis forbade Mongol nobles from hunting during breeding seasons to preserve wildlife, an early conservation effort amid his conquests.

#### The Storm of Conquest: Building the Largest Empire

Genghis Khan’s empire-building began with China. In 1207, he subdued the Western Xia (Tanguts), forcing tribute. By 1211, he targeted the Jin dynasty, whose heavy taxes on nomads fueled resentment. Crossing the Gobi Desert, his 90,000 horsemen used feigned retreats to lure Jin armies into ambushes. At Badger Mouth in 1211, they annihilated 200,000 Jin troops.

Sieging Zhongdu (Beijing) in 1214-15, Mongols employed Chinese defectors for catapults and gunpowder. The city fell amid famine, with reports of cannibalism. Genghis diverted the Yellow River to flood enemies, showcasing engineering ingenuity.

Westward, the 1218 insult by Khwarezm Shah Muhammad—killing Mongol envoys—ignited fury. Genghis mobilized 200,000 men in 1219, splitting forces for a multi-front assault. Subutai and Jebe pursued the shah across Persia, while Genghis sacked Bukhara, where he declared himself “the scourge of God.” Samarkand fell after betrayal, its artisans spared for Mongol use.

The campaign’s brutality was strategic: massacres at resistant cities like Merv (over 1 million killed) encouraged surrender elsewhere. By 1223, Mongols raided into Russia at the Battle of Kalka River, defeating Kievan Rus’ princes. Explorations reached Georgia and Volga Bulgaria.

Back east, Genghis quelled Xia rebellions in 1225-27. His armies incorporated diverse technologies: Persian doctors, Chinese siege experts, and Muslim traders.

Educational insight: Mongol mobility—horsemen traveling 100 miles daily with multiple mounts—combined with intelligence networks made them unstoppable. They promoted trade, protecting the Silk Road, fostering cultural exchange from Europe to Asia.

Fun element: Legends say Genghis sought immortality from Taoist monk Qiu Chuji, who advised moderation—ironic for a conqueror!

#### The Final Campaign and Mysterious Death on August 18, 1227

In 1226, aged about 65, Genghis launched a final punitive expedition against the Western Xia for allying with enemies. Despite a hunting fall injuring his knee, he pressed on, capturing cities like Ganzhou. By spring 1227, the Xia capital Yinchuan was besieged.

Accounts of his death vary. The Secret History claims illness from the fall worsened in the Liupan Mountains’ heat. Persian historian Juvayni says he was struck by lightning or poisoned. Some legends allege assassination by a Xia princess. Modern theories suggest typhus or plague.

On August 18, 1227, Genghis died, reportedly advising his sons on succession. His body was secretly transported to Mongolia, with escorts killing witnesses to conceal the burial site—possibly in the Khentii Mountains, unmarked as per tradition. The Xia surrendered soon after, their emperor executed.

This secrecy fueled myths: his tomb allegedly holds treasures, cursed to doom finders. Recent archaeology uses non-invasive tech to search, but it remains undiscovered.

#### Succession and Immediate Aftermath

Genghis designated Ögedei as successor in 1219, confirmed before death. Jochi, suspected of illegitimacy, was sidelined (he died in 1227); Chagatai governed Central Asia; Tolui received Mongolia. Ögedei was enthroned in 1229, continuing expansions.

The empire peaked under Ögedei and successors, reaching from Korea to Hungary by 1279 under Kublai. But divisions emerged: the Golden Horde, Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate, and Yuan dynasty fractured it.

#### The Enduring Legacy: Reshaping the World

Genghis Khan’s empire covered 9 million square miles, influencing genetics (8% of Asian men carry his Y-chromosome), trade (Pax Mongolica enabled Marco Polo), and culture. He promoted literacy, religious freedom, and women’s rights (relative to era). Yet, his conquests killed millions—perhaps 40 million, reducing global population by 11%.

In Mongolia, he’s a national hero; elsewhere, views range from barbarian to genius. UNESCO named 1990 his 800th anniversary year.

Fun twist: Modern depictions, like in video games or films, often exaggerate his ferocity, but he was a strategic innovator, not just a destroyer.

#### From Khan to You: Applying Genghis Khan’s Legacy to Your Life Today

Genghis Khan’s life teaches that from adversity rises greatness. His outcome—uniting fractious groups into a superpower—shows how vision, adaptability, and loyalty build success. Here’s how you can benefit today, turning historical wisdom into personal triumph.

– **Embrace Resilience in Setbacks**: Like Temüjin’s exile, view failures as forging experiences. If you lose a job, use it to skill-up, networking like he did with allies.

– **Build Merit-Based Networks**: Promote talent over nepotism. In your career, mentor diverse team members, creating a loyal “tumen” that propels projects forward.

– **Adapt Strategies Dynamically**: Mimic Mongol tactics—feign retreats in negotiations to draw out opponents’ weaknesses, then strike decisively.

– **Foster Unity and Tolerance**: Apply his Yassa by encouraging diverse viewpoints in your community or workplace, boosting innovation.

– **Pursue Lifelong Learning**: Genghis adopted foreign tech; you can learn new skills via online courses, expanding your “empire” of knowledge.

**Your 30-Day Khan-Inspired Plan**:

– **Days 1-7: Reflect and Ally** – Journal past hardships, identify 3 “allies” (mentors/friends) to connect with weekly.

– **Days 8-14: Strategize Conquests** – Set a big goal (e.g., promotion), break into decimal steps like Mongol units, adapt as needed.

– **Days 15-21: Build Loyalty** – Help others succeed, organize a group activity to foster bonds.

– **Days 22-28: Expand Horizons** – Learn a new skill (e.g., coding/archery for fun), apply it practically.

– **Days 29-30: Celebrate and Plan Ahead** – Review progress, host a “kurultai” dinner to share wins, set next goals.

Channel the Khan’s spirit—you’re not conquering lands, but your potential. Rise, unite, adapt, and thrive!