Imagine a world where a simple argument between a husband and wife could lead to severe punishment under the law—100 brutal floggings for accidentally tearing a piece of paper money. Sounds like a plot from a dramatic historical novel, right? But on August 16, 1384, this very scenario unfolded in the court of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of China’s Ming Dynasty. What could have been a tragic tale of rigid justice turned into an inspiring act of pardon, showcasing the human side of one of history’s most formidable rulers. This event, though small in scale, offers a window into the complexities of 14th-century China, a time of rebirth after Mongol rule, sweeping reforms, and a quest for stability. In this blog, we’ll dive deep into the historical context, exploring the emperor’s life, his dynasty’s foundations, and the intricacies of Ming society. Then, we’ll bridge the centuries to see how this act of mercy can inspire us today, turning ancient wisdom into practical, life-changing habits. Buckle up for a journey that’s equal parts history lesson and motivational boost—because who knew a torn banknote could teach us so much?

### The Turbulent Backdrop: China Before the Ming Dynasty

To truly appreciate the significance of that fateful day in 1384, we must rewind the clock to the chaotic era that preceded the Ming Dynasty. The 14th century in China was marked by the decline of the Yuan Dynasty, established by Kublai Khan in 1271 after the Mongol conquest of the Song Dynasty. The Yuan rulers, descendants of Genghis Khan, brought a foreign flavor to Chinese governance, blending nomadic traditions with Confucian bureaucracy. However, by the mid-1300s, their grip was weakening. Natural disasters plagued the land: massive floods along the Yellow River in 1344 displaced millions, famines ravaged populations, and epidemics, including what some historians link to the Black Death, claimed countless lives.

Amid this turmoil, secret societies and rebel groups emerged, fueled by resentment against Mongol overlords who favored foreigners in high positions and imposed heavy taxes on the Han Chinese majority. One such group was the Red Turban Rebellion, inspired by millenarian Buddhist beliefs in a coming savior. The rebels wore red headscarves as a symbol of their cause, drawing from the White Lotus Society’s prophecies of a “King of Light” who would restore justice. It was into this powder keg that our protagonist, Zhu Yuanzhang—the future Hongwu Emperor—was born.

Zhu’s early life reads like a rags-to-riches epic. Born on October 21, 1328, in a impoverished peasant family in Zhongli village (modern-day Fengyang, Anhui Province), he was the youngest of several children. His parents, struggling tenant farmers, named him Zhu Chongba, meaning “Heavy Eight,” reflecting the hardships of his birth during a time of drought and poverty. Tragedy struck early: in 1344, when Zhu was just 16, floods and plague wiped out his entire family—parents, brothers, and sisters—leaving him orphaned and destitute. With no means to bury them properly, he wrapped their bodies in mats and laid them to rest in a shallow grave.

Desperate, Zhu sought refuge in a nearby Buddhist monastery, Huangjue Temple, where he became a novice monk. Life there was no easier; famine forced the monastery to close temporarily, and Zhu wandered as a beggar-monk for three years, traveling through the Huai River valley. These years exposed him to the suffering of the common people—starving farmers, corrupt officials, and the brutality of Yuan soldiers. He learned to read and write, studying Buddhist scriptures and classical texts, which would later influence his rule. By 1352, at age 24, Zhu returned to the monastery but soon joined the Red Turban rebels in Haozhou, a decision that catapulted him into the annals of history.

Zhu’s ascent was meteoric. Starting as a lowly foot soldier, his charisma, strategic mind, and bravery earned him rapid promotions. He allied with Guo Zixing, a rebel leader, and married Guo’s adopted daughter, Lady Ma (later Empress Ma), who became his lifelong confidante and advisor. By 1355, Zhu commanded his own forces, capturing key cities like Chuzhou and Hezhou. His big break came in 1356 when he seized Nanjing (then called Jiqing), establishing it as his base. Nanjing’s strategic location on the Yangtze River allowed him to control trade routes and build a navy.

The 1360s were a decade of warfare. Zhu defeated rival warlords, including Chen Youliang in the epic Battle of Lake Poyang in 1363—one of the largest naval battles in history, involving hundreds of thousands of troops and massive warships. Chen’s death solidified Zhu’s dominance in the south. He then turned north, expelling the Mongols. On January 23, 1368, in Nanjing, Zhu proclaimed himself emperor, adopting the era name Hongwu (“Vastly Martial”) and founding the Ming (“Bright”) Dynasty. The Yuan capital, Dadu (modern Beijing), fell later that year, marking the end of Mongol rule in China proper.

The Ming Dynasty’s establishment was more than a power grab; it was a restoration of Han Chinese sovereignty after nearly a century of foreign domination. Hongwu aimed to revive traditional Chinese institutions, blending Confucianism with autocratic control. His reign (1368–1398) was characterized by centralization of power, agrarian reforms, and a focus on moral governance. But it wasn’t all smooth sailing—paranoia about plots led to purges, and his strict laws sometimes bordered on tyranny. Yet, moments like the 1384 pardon reveal a ruler capable of empathy.

### Hongwu’s Sweeping Reforms: Building a New Empire

Once in power, the Hongwu Emperor didn’t rest on his laurels. He embarked on ambitious reforms to stabilize and strengthen his fledgling dynasty. Let’s break them down, as they provide crucial context for the 1384 event.

First, land reform was paramount. The Yuan era had seen land concentrated in the hands of Mongol nobles and corrupt officials, leaving peasants landless and resentful. Hongwu confiscated vast estates from the wealthy and redistributed them to the poor. In 1370, he ordered a nationwide land survey, registering households and allocating plots based on family size—typically 15 mu (about 2.5 acres) per person in the north and more in the fertile south. Soldiers received larger allotments, up to 50 mu, to encourage self-sufficiency. By 1393, these efforts had resettled millions, boosting agricultural output. Rice, wheat, and cotton production soared, and new crops like sweet potatoes (introduced later) would further transform the economy.

To enforce this, Hongwu created the lijia system, organizing rural households into groups of 110 families (10 leaders and 100 commoners) for mutual surveillance, tax collection, and labor corvee. This community-based structure ensured taxes were paid in grain, which filled imperial granaries and prevented famines. However, it also fostered a culture of collective responsibility, where one family’s misdeed could punish the group—a precursor to modern social credit systems in some eyes.

Military reforms were equally innovative. Drawing from his rebel days, Hongwu established the weisuo system in 1364, even before becoming emperor. This created hereditary military households, where soldiers farmed in peacetime and fought when called. Guards (wei) of 5,600 men were stationed across the empire, divided into battalions and companies. By the 1390s, there were over 300 guards and a standing army of about 1.2 million. To prevent coups, Hongwu abolished the prime minister position in 1380 after executing his chancellor Hu Weiyong for alleged treason, centralizing power in his hands. He also enfeoffed his sons as princes with military commands on the borders, creating a network of loyal family strongholds.

The legal system under Hongwu was a blend of tradition and innovation. He commissioned the Great Ming Code (Da Ming Lü) in 1367, finalized in 1397, based on the Tang Code of 653 but infused with Confucian ethics. The code covered crimes from treason to petty theft, emphasizing filial piety, social harmony, and punishment proportional to status—officials faced harsher penalties for corruption. Justice was administered through a hierarchy of magistrates, with appeals reaching the emperor. Hongwu often intervened personally, reviewing cases to ensure fairness, though his paranoia led to mass executions, like the 1380 Hu Weiyong purge that claimed 30,000 lives.

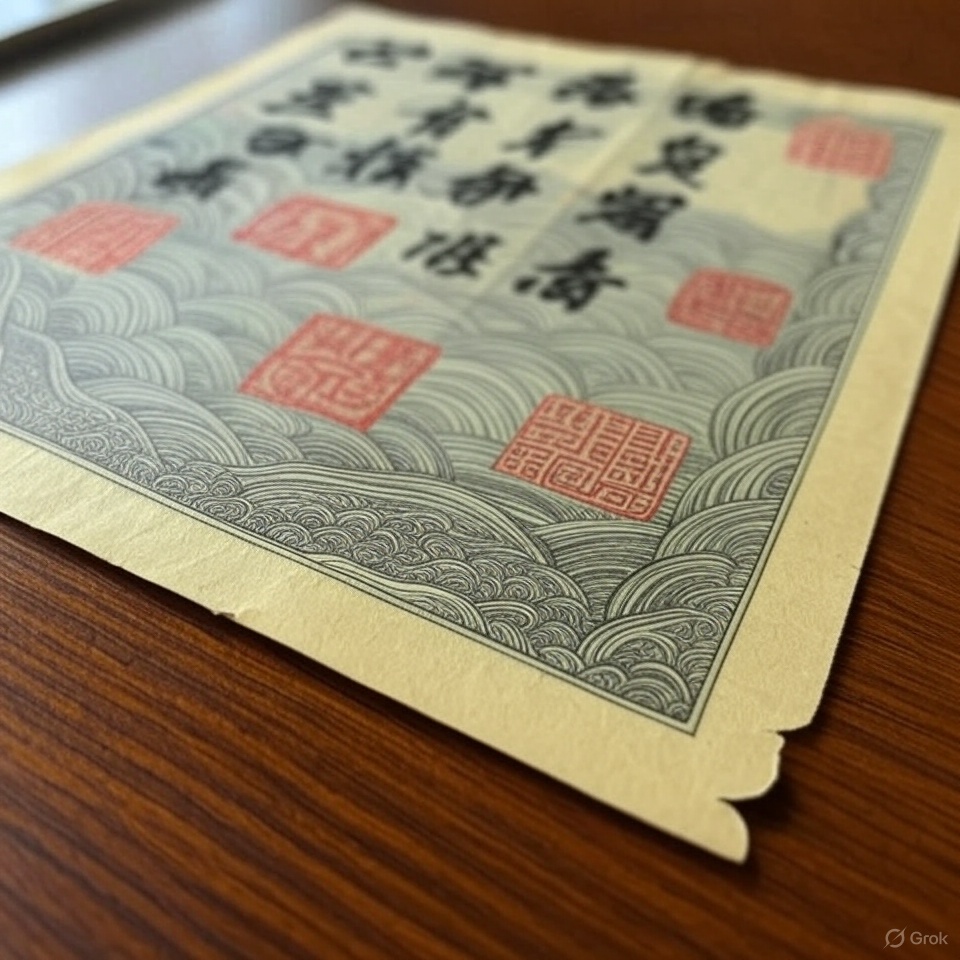

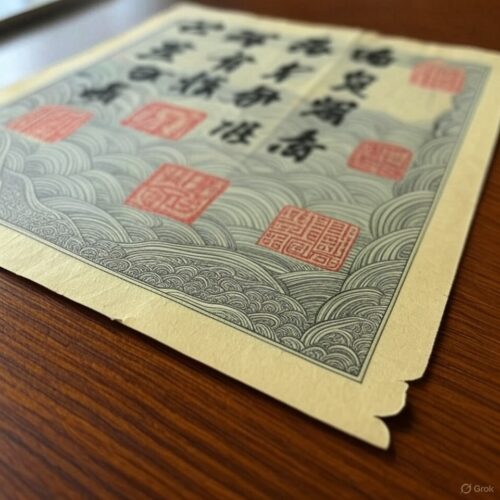

Currency reform was a bold but troubled endeavor. China had pioneered paper money under the Song and Yuan dynasties, but inflation and counterfeiting plagued the system. Hongwu introduced the Da Ming Baochao in 1375, unbacked paper notes meant to replace copper coins and silver ingots. Printed on mulberry bark paper with intricate designs to deter fakes, these notes were mandatory for taxes and trade. However, overprinting caused hyperinflation; by 1380, a note’s value had plummeted. Laws prohibited using precious metals, but merchants ignored them, preferring silver. Destroying or defacing notes was a grave offense, equated to tampering with government seals, punishable by 100 floggings or worse.

This brings us to the heart of our story: paper money’s role in daily life. In Ming China, these notes were more than currency; they symbolized imperial authority. Tearing one was like desecrating a state document. Yet, in a society recovering from war, quarrels over money were common, especially among the poor who relied on these fragile bills for survival.

### The Fateful Day: August 16, 1384, and the Emperor’s Pardon

Now, let’s zoom in on that pivotal moment. On August 16, 1384, in the imperial court at Nanjing, the Hongwu Emperor—now in his mid-50s and 16 years into his reign—presided over a routine legal hearing. The case involved an unnamed couple from a humble background, likely peasants or small traders. According to historical records, including the Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming) and later annals, the pair had argued fiercely over a handful of paper money bills. In the heat of the moment, the notes were torn apart.

Under the Great Ming Code, this act was no minor mishap. Article 273 classified defacing currency as destruction of official documents, a crime against the state. The prescribed punishment? One hundred strokes of the heavy rod—a flogging that could cripple or kill. The law was designed to protect the fragile economy and maintain respect for imperial edicts. Magistrates had already convicted the couple, and the case escalated to the emperor for final judgment, as was custom for unusual or symbolic matters.

What happened next surprised everyone. Hongwu, known for his draconian enforcement, delved into the details. He learned the tear was accidental, born of a domestic spat rather than malice or counterfeiting intent. Perhaps reminded of his own impoverished youth and marital squabbles (Empress Ma often tempered his temper), the emperor showed mercy. He pardoned the couple outright, waiving the floggings and any fines. This decision was recorded as an example of benevolent rule, aligning with Confucian ideals of ren (humaneness) where the ruler acts as a father to his people.

While the event seems minor, it was emblematic of Hongwu’s style. He frequently reviewed petitions, sometimes handling thousands in a day. Other pardons dotted his reign: in 1376, he forgave tax arrears during a drought; in 1390, he amnestied political prisoners. But this case stood out for its personal touch, humanizing a leader often portrayed as paranoid. Historians speculate it served propaganda purposes, demonstrating the emperor’s wisdom to a populace wary of strict laws.

The aftermath? The couple likely returned home grateful, their story spreading as folklore. For the dynasty, it reinforced currency’s importance while showing flexibility. Hongwu’s reign continued until 1398, when he died at 69, succeeded by his grandson Jianwen. His legacy endured: the Ming lasted until 1644, a golden age of culture, exploration (think Zheng He’s voyages), and porcelain artistry.

But what made this event significant? In a era of reconstruction, it highlighted the tension between rigid law and human compassion. Hongwu’s background as a former beggar-monk made him attuned to commoners’ plights, yet his reforms demanded order. This pardon bridged that gap, offering a model of leadership that balanced justice with mercy.

### Broader Impacts: Mercy in Ming Society and Beyond

Expanding outward, the 1384 pardon fits into the larger tapestry of Ming social dynamics. Society was stratified: at the top, the emperor and scholar-officials selected via reinstated civil service exams (from 1384 onward, emphasizing Neo-Confucian texts). Below, merchants thrived despite low status, artisans crafted wonders like the Forbidden City (built later under Yongle), and peasants formed the backbone.

Women’s roles were confined but influential; Empress Ma, a key advisor, advocated for leniency in several cases. Footbinding emerged among elites, symbolizing beauty but limiting mobility. Education spread, with village schools teaching classics, fostering literacy rates higher than in contemporary Europe.

Economically, despite currency woes, Ming China boomed. Silver inflows from Japan and the Americas (via Manila Galleons later) fueled trade. Porcelain, silk, and tea exports created global demand. Culturally, novels like “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” were compiled, and theater flourished.

Hongwu’s mercy also echoed in foreign policy. He sent envoys to Southeast Asia, establishing tributary relations without conquest. Domestically, he built the Great Wall’s precursors and irrigated farmlands.

Yet, challenges persisted: purges eroded trust, and isolationism set in. By the late Ming, corruption and invasions led to fall. Still, Hongwu’s act reminds us that even autocrats can choose kindness.

### From Ancient Pardon to Modern Empowerment: Applying Mercy Today

Now, fast-forward 641 years to our fast-paced world. What can a 14th-century pardon teach us? In an age of cancel culture, road rage, and workplace conflicts, the Hongwu Emperor’s choice to forgive over punish offers a powerful antidote. Mercy isn’t weakness—it’s a strategic tool for personal growth, stronger relationships, and inner peace. Research from psychology shows forgiveness reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, and boosts happiness. By applying this historical fact, you can transform small grievances into opportunities for growth. Here’s how it benefits your individual life, with specific bullet points and a actionable plan.

**Specific Benefits of Embracing Mercy in Daily Life:**

– **In Personal Relationships:** Holding grudges over minor arguments, like a spouse forgetting an anniversary, drains emotional energy. Forgiving quickly, as Hongwu did, fosters trust and deepens bonds, leading to happier marriages or friendships. For example, instead of escalating a fight over household chores, pause and pardon, preventing resentment buildup.

– **At Work or School:** When a colleague takes credit for your idea or a classmate copies your notes without asking, reacting with mercy avoids toxic dynamics. It positions you as a leader, encouraging collaboration and opening doors to mentorship. Studies from Harvard Business Review show forgiving teams are 22% more productive.

– **For Self-Improvement:** Self-mercy is key—pardoning your own mistakes, like missing a gym session, reduces self-sabotage. This builds resilience, helping you stick to goals like weight loss or learning a skill, with less guilt-fueled procrastination.

– **In Community Interactions:** Road rage or online trolls? Choosing mercy de-escalates conflicts, promoting safety and harmony. It models positive behavior, inspiring others and creating a ripple effect in your neighborhood or social circle.

– **Health and Well-Being:** Chronic anger links to heart disease; mercy releases endorphins, improving sleep and immunity. Applying Hongwu’s lesson daily can add years to your life, as per Mayo Clinic findings on forgiveness therapy.

**A Step-by-Step Plan to Incorporate Mercy into Your Life:**

- **Reflect Daily (5 Minutes):** Start each morning journaling one past grievance—big or small—and consciously decide to pardon it. Ask: “What was the intent? How does holding on hurt me?” This mirrors Hongwu’s case review.

- **Practice Pause in Conflicts:** When upset, count to 10 before responding. Visualize the 1384 couple’s tearful relief upon pardon, then choose words of understanding. Apply this in real-time, like during a family dinner debate.

- **Set Mercy Goals Weekly:** Identify three situations to forgive—e.g., a friend’s lateness, a boss’s criticism, your own diet slip. Track in a app or notebook, rewarding yourself with a treat for success.

- **Seek External Input:** Discuss grudges with a trusted friend or therapist, gaining perspective like Hongwu’s court advisors. Join a forgiveness workshop or read books like “The Book of Forgiving” by Desmond Tutu.

- **Review and Adjust Monthly:** At month’s end, assess how mercy improved your mood, relationships, or productivity. Adjust the plan, perhaps adding meditation for deeper empathy.

By weaving this ancient act into your routine, you’ll not only honor history but craft a more fulfilling life. Mercy isn’t just for emperors—it’s your superpower for thriving today. So, next time a “torn banknote” moment arises, channel Hongwu and choose pardon. Your future self will thank you!