Welcome to a journey back in time to a scorching August afternoon in 1385, where the fate of a nation hung by the thread of a hilltop defense. The Battle of Aljubarrota wasn’t just a clash of arms; it was a symphony of strategy, courage, and sheer audacity that echoed through centuries. Picture this: a small Portuguese force, outnumbered five to one, staring down a massive Castilian army backed by French knights and Aragonese allies. Yet, through clever tactics and unbreakable resolve, they turned the tide. This isn’t a fairy tale—it’s raw history, packed with intrigue, betrayal, and triumph. We’ll dive deep into the details of this pivotal event, exploring its roots in royal succession crises, the gritty battlefield maneuvers, and its ripple effects on European power dynamics. Then, we’ll bridge the gap to today, showing how the lessons from that dusty field can supercharge your personal growth with practical, actionable steps. Get ready for an educational rollercoaster that’s as fun as it is enlightening—think epic underdog story meets motivational masterclass!

#### The Turbulent Backdrop: Portugal’s Crisis of Succession (1383–1385)

To understand Aljubarrota, we must rewind to the chaotic years leading up to it. The 14th century was a brutal era for Europe. The Hundred Years’ War raged between England and France, the Black Death had decimated populations, and famines gnawed at societies. Portugal, a small kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula’s edge, was no exception. King Ferdinand I, known as “the Handsome” or “the Inconstant” depending on who you asked, ruled from 1367 to 1383. His reign was marked by three wars with Castile, Portugal’s larger neighbor to the east, and a series of shifting alliances.

Ferdinand’s biggest headache was his lack of a male heir. His only surviving child was Princess Beatrice, born in 1373. In a desperate bid to secure peace and the throne’s future, Ferdinand signed the Treaty of Salvaterra de Magos in April 1383 with King Juan I of Castile. This pact arranged Beatrice’s marriage to Juan, stipulating that their offspring would inherit Portugal. If no children came, the crown would revert to Castilian heirs, effectively merging the kingdoms. But this was a powder keg. Many Portuguese nobles, merchants, and commoners dreaded losing their independence to Castile, which was seen as a cultural and political bully.

Ferdinand died on October 22, 1383, plunging Portugal into an interregnum. Queen Leonor Teles, Ferdinand’s widow, became regent for Beatrice, but her rule was unpopular. Leonor was rumored to have an affair with João Fernandes Andeiro, a Galician noble and Count of Ourém, who wielded immense influence. Tensions boiled over when John of Aviz, an illegitimate son of Ferdinand’s father Peter I and Grand Master of the Military Order of Aviz, emerged as a champion of Portuguese nationalism.

On December 6, 1383, John orchestrated Andeiro’s assassination in Lisbon’s royal palace, sparking a revolution. Lisbon’s populace rallied behind him, proclaiming him “rector and defender of the realm.” Queen Leonor fled to Santarém, appealing to Juan I of Castile for help. Juan invaded in January 1384, forcing Leonor to abdicate and installing Beatrice as queen under his control. But the Portuguese resistance hardened. John of Aviz, now the de facto leader, sought allies abroad.

Enter Nuno Álvares Pereira, a noble from a prominent family and John’s key military mind. In April 1384, at the Battle of Atoleiros, Pereira’s 1,400 Portuguese troops defeated a 5,000-strong Castilian force using innovative defensive tactics: dismounted knights formed tight infantry squares, repelling cavalry charges—a preview of Aljubarrota’s genius. That summer, Juan besieged Lisbon with 20,000 men, but plague and supply shortages, worsened by Pereira’s guerrilla raids, forced a retreat in September 1384.

John solidified his position by courting international support. He negotiated with the Papacy and, crucially, England, which was at war with France (Castile’s ally). In October 1384, English King Richard II promised aid. By April 1385, the Portuguese Cortes (assembly) in Coimbra acclaimed John as King John I, rejecting Beatrice and annexing pro-Castilian towns like Caminha and Braga. Juan I, furious, mustered a massive army for a final invasion, setting the stage for Aljubarrota.

#### Assembling the Armies: Forces and Preparations

By summer 1385, Juan I of Castile had assembled a formidable force of about 31,000 men—the largest army Iberia had seen in centuries. It included 15,000 infantry, 6,000 heavy cavalry lances (each lance typically three to five riders), 8,000 crossbowmen, and over 2,000 elite French heavy knights from companies like those of Sir Geoffroy de Chargny. Allies from Aragon and Genoa added mercenaries, including crossbow experts. The army even brought 15 primitive bombards (early cannons) and was supported by a fleet for coastal operations. Juan’s goal was total conquest: capture Lisbon, crush John I, and install Beatrice.

Opposing them was John I’s Portuguese army, roughly 6,600 strong—a ragtag but determined mix. The core was 2,000 heavy infantry and 1,700 crossbowmen, bolstered by 800 mounted knights who fought dismounted. Crucially, English allies arrived in May 1385: about 200 longbowmen and 500 men-at-arms, mostly veterans from the Hundred Years’ War, including Gascons. A Florentine volunteer, Galioto Belfiore, joined too. The Portuguese lacked the Castilians’ numbers but had superior morale, local knowledge, and innovative leaders like Pereira, appointed Constable of Portugal.

As Juan’s army marched south from Ciudad Real in June 1385, ravaging Portuguese lands, John and Pereira scouted defensive positions. They chose São Jorge hill near Aljubarrota, 100 km north of Lisbon—a flattened plateau flanked by creeks, ideal for funneling attackers into kill zones. The Portuguese dug trenches, scattered caltrops (spiked iron devices to lame horses), and prepared pitfalls, drawing from English tactics at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356).

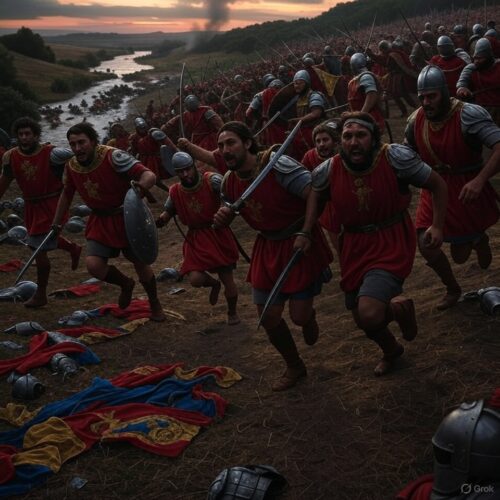

#### The Battle Unfolds: Tactics, Chaos, and Heroism

August 14, 1385, dawned hot and dry. Juan’s army, exhausted from a 15-km march, arrived around noon. Initially, the Castilians tried to bypass the hill, circling to attack from the gentler southern slope. But the Portuguese, spotting this, swiftly repositioned— a feat of discipline under Pereira’s command.

By 6 p.m., with the sun low, Juan ordered the assault. The French knights, eager for glory and promised lands in Portugal, charged first: 2,000 heavy cavalry thundering uphill. But the narrow front, constricted by creeks, turned the charge into a bottleneck. Portuguese and English archers unleashed volleys—longbows piercing armor at 300 yards, crossbows adding density. Horses fell on caltrops, knights tumbled into trenches. The French reached the lines but were met by dismounted Portuguese knights in tight formation, spears and axes hacking away.

Chronicler Jean Froissart, drawing from eyewitnesses, described the French being “cut to pieces” without support. Internal rivalries plagued the Castilians: nobles reportedly delayed aid, jealous of French promises. Many French were slain or captured; John I ordered prisoners executed mid-battle to free guards for the fight—a grim but practical decision.

As dusk fell, the main Castilian force advanced: waves of infantry and dismounted knights climbing the hill. Again, the terrain funneled them into arrow storms. The Portuguese center held firm, with flanks—the “Ala dos Namorados” (Wing of Lovers, young nobles fighting for honor) and “Ala de Madressilva” (Honeysuckle Wing)—enveloping the attackers. Hand-to-hand combat ensued: swords clashing, axes cleaving shields. Pereira’s reserves plugged gaps, while English longbowmen rained death from the sides.

Panic spread in Castilian ranks. Juan I, watching from afar, saw his vanguard shatter. When Portuguese flanks closed like a trap, the Castilians routed. Pursuit was merciless: fleeing troops were hunted through the night, many drowned in creeks or slain by locals. Legend adds color—a baker woman named Brites de Almeida allegedly killed seven hiding Castilians with her shovel, earning the moniker “Padeira de Aljubarrota.” Whether true or not, it captures the folk heroism.

#### Aftermath and Casualties: A Crushing Defeat

The battle lasted barely two hours but was devastating. Portuguese casualties were light: around 1,000 dead or wounded, thanks to defensive positioning. Castilians suffered catastrophically: 5,000 killed on the field, thousands more in pursuit—total losses up to 13,000, including nobles like Pedro Álvares Pereira (a Portuguese traitor fighting for Castile). French knights lost heavily; survivors like Chargny were ransomed. Juan I fled to Santarém, then back to Castile, abandoning artillery and baggage trains loaded with gold.

In October 1385, Pereira struck again at Valverde, defeating another Castilian force. The war ended with the Treaty of Segovia in 1411, but Aljubarrota had already sealed Portugal’s fate.

#### Long-Term Significance: Birth of a Nation and Global Ripples

Aljubarrota wasn’t just a victory; it birthed modern Portugal. It confirmed John I’s rule, establishing the House of Aviz, which reigned until 1580. The battle ensured Portuguese independence, preventing absorption into Castile (later Spain). This autonomy fueled the Age of Discoveries: under Aviz kings like Manuel I, explorers like Vasco da Gama and Bartolomeu Dias opened sea routes to India and Africa, building a global empire.

Diplomatically, it forged the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. In 1386, John I signed the Treaty of Windsor with England—the world’s oldest active alliance, aiding both in wars like Waterloo and WWII. Militarily, Aljubarrota showcased infantry tactics over cavalry, influencing Renaissance warfare and foreshadowing gunpowder eras.

Culturally, it’s etched in Portuguese identity. The battlefield is a national monument, with the Monastery of Batalha (built 1386–1434) commemorating the win—a Gothic masterpiece honoring the dead. Annual reenactments and festivals keep the spirit alive, blending history with fun fairs and medieval feasts. The “Mad Baker” legend inspires tales, songs, and even pastries baked in shovel shapes!

Economically, the victory stabilized Portugal, boosting trade with England and Flanders. It also highlighted social dynamics: commoners and merchants backed John I, shifting power from feudal lords.

In broader European context, Aljubarrota weakened Castile during the Hundred Years’ War, indirectly aiding England. It exemplified how small nations could defy empires through unity and innovation—a theme resonating in later struggles like the Dutch Revolt or American Revolution.

#### From Medieval Battlefield to Modern Life: Benefits and a Personal Action Plan

While Aljubarrota’s historical weight is immense, its core lesson—triumphing against overwhelming odds through preparation, unity, and adaptability—offers timeless motivation. Imagine channeling that defiant spirit in your daily grind: facing a tough job interview, launching a side hustle, or overcoming personal setbacks. The outcome? A more resilient, confident you. Here’s how this historical fact benefits your individual life today, with specific bullet points on applications and a step-by-step plan to implement them. Let’s turn history into your superpower!

– **Embrace Defensive Positioning in Challenges**: Just as the Portuguese chose the hill for advantage, position yourself strategically in life. For example, before a big presentation, research your audience thoroughly to anticipate questions, turning potential pitfalls into strengths.

– **Leverage Alliances for Support**: John I’s English allies were game-changers; build your network. Reach out to a mentor via LinkedIn for career advice, or join a community group for fitness goals, multiplying your resources like those longbowmen amplified the Portuguese line.

– **Innovate Tactics Against Superior Odds**: Pereira’s trenches and caltrops innovated warfare; apply creativity to problems. If debt feels like a Castilian army, use apps like Mint to track spending and create a “defensive square” budget that prioritizes essentials.

– **Foster Unity in Teams or Relationships**: The Portuguese flanks worked in harmony; cultivate teamwork. In a group project, assign roles based on strengths, ensuring everyone feels valued, preventing “routs” like miscommunication.

– **Turn Setbacks into Legends**: The Mad Baker myth shows how ordinary acts become heroic; reframe failures. After a rejected job application, journal what you learned, transforming it into a motivational story for future interviews.

**Your 30-Day Aljubarrota-Inspired Resilience Plan**:

- **Days 1-7: Scout Your Battlefield** – Identify a personal challenge (e.g., improving health). Journal daily: What are the “odds” against you? Research solutions, like free online courses for skill-building.

- **Days 8-14: Build Defenses** – Prepare tools. For career growth, update your resume and practice interviews with a friend, mimicking trenches against rejection.

- **Days 15-21: Forge Alliances** – Connect with three people: a colleague for feedback, a family member for encouragement, an online forum for tips. Schedule weekly check-ins.

- **Days 22-28: Execute with Adaptability** – Take action, like applying for jobs or starting a workout routine. Adapt if obstacles arise—switch gyms if one doesn’t fit, like repositioning on the hill.

- **Days 29-30: Celebrate and Reflect** – Review progress. Treat yourself (maybe bake “Mad Baker” cookies!), note wins, and plan the next “battle.” Repeat monthly for ongoing growth.

By applying Aljubarrota’s lessons, you’ll not only honor history but ignite your potential. Remember, if a outnumbered army could shape empires, imagine what you can achieve. Charge forward—your hill awaits!