On this very day, June 24th, in 1947, a private pilot named Kenneth Arnold was flying his CallAir A-2 single-engine plane over the glaciated peaks of the Cascade Mountains in Washington state. He wasn’t looking for anything extraordinary. His mission was mundane: he was searching for the wreckage of a downed military transport plane, hoping to claim a large cash reward. The sky was crystal clear. But what he saw next, near the majestic silhouette of Mount Rainier, would not only change his life but would also permanently alter our cultural vocabulary and ignite a global phenomenon that burns to this day.

He saw a string of nine objects. They were brilliantly bright, flying in a staggered, echelon formation. They moved with a speed and fluidity that defied any explanation. He clocked them moving from Mount Rainier to Mount Adams, a distance of nearly 50 miles, in just one minute and forty-two seconds. This calculated to a speed of over 1,700 miles per hour, a velocity unheard of for any known aircraft in 1947. He later described their motion to a reporter as being like a “saucer would if you skipped it across the water.” The reporter seized on the image, and a headline was born: “Flying Saucers.” The modern age of UFOs had begun.

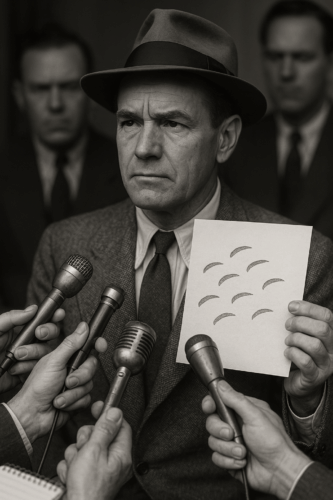

Kenneth Arnold was a respected businessman and an experienced pilot, not a fantasist. He was a credible witness describing an incredible event. His sighting triggered hundreds, then thousands, of similar reports across the nation. The government launched investigations. The public became captivated. But at its core, this is a story about one person encountering something so far outside his frame of reference that he struggled to even describe it. He saw something that simply did not fit.

Kenneth Arnold was a respected businessman and an experienced pilot, not a fantasist. He was a credible witness describing an incredible event. His sighting triggered hundreds, then thousands, of similar reports across the nation. The government launched investigations. The public became captivated. But at its core, this is a story about one person encountering something so far outside his frame of reference that he struggled to even describe it. He saw something that simply did not fit.

And right there is where this 78-year-old event becomes deeply, personally relevant to you today. We all have “flying saucers” appear in our lives. They are the unexpected job offers, the disruptive new technologies, the sudden personal insights, the radical business ideas, or the life-altering opportunities that don’t fit our current map of reality. They are the things that challenge our assumptions and force us to look at the world differently. Most people dismiss them as impossible. But learning from Kenneth Arnold gives us a framework for how to spot them, how to navigate the reaction, and how to use them to pilot our lives into new and extraordinary territory.

Benefit Today: Train Yourself to See the Unseen Opportunity

The other pilots flying in the area that day didn’t report seeing anything. Arnold saw the objects because he was actively scanning the horizon, looking for something out of the ordinary. In our lives, we are often so focused on our flight plan—our daily tasks, our routines, our established goals—that we fail to see the incredible, game-changing opportunities flying right past us. You can train your perception to be more like Arnold’s: open, active, and ready for the unexpected.

- Challenge Your Mental Models: We all have mental models of how the world works. “That’s not how my industry functions,” “I’m not the kind of person who does that.” These models are comfortable, but they are also cages. Actively question them.

- Practice Active Observation: Don’t just look; see. Pay attention to the details, the anomalies, the little things that seem slightly “off” in your work or life. This is often where the most significant opportunities hide.

- Expose Yourself to New Data: If you only read about your own field or talk to people who think like you, you will never have a paradigm shift. Intentionally consume information from unrelated fields. It “cross-pollinates” your brain and allows you to make novel connections.

- Ask “What If?” not “Is That Possible?”: When confronted with a strange new idea, the default reaction is to judge its feasibility. Instead, start with curiosity. “What if that were true? What would that make possible?” This opens doors in your mind that were previously locked.

Your Personal Plan for Developing “Saucer-Spotting” Perception:

Your Personal Plan for Developing “Saucer-Spotting” Perception:

- Step 1: Conduct a “Pattern Interrupt.” Once a week, deliberately break one of your routines. Take a different route to work. Work from a different location. Read a magazine you’d never pick up. This forces your brain out of autopilot and into an active, observational mode.

- Step 2: Start a “Curiosity Log.” For 30 days, write down one question each day about something you don’t understand. It could be big or small. At the end of the month, you’ll have 30 avenues for new learning and you’ll have trained yourself to live in a state of inquiry.

- Step 3: Schedule a “Cross-Pollination” Meeting. Once a month, have lunch or coffee with someone from a completely different department, industry, or walk of life. Your only goal is to understand their world. Don’t sell, don’t pitch—just learn.

- Step 4: Practice “Assumption Reversal.” Take a core belief you hold about your work or life (“I must work 8 hours a day to be productive”). Spend 15 minutes seriously brainstorming what would happen and what would be possible if the complete opposite were true.

Benefit Today: Navigate Skepticism with Unshakable Integrity

Kenneth Arnold was not celebrated, at first. He was ridiculed by many and subjected to intense, often dismissive, investigation. When you bring a new idea to your boss, propose a major life change to your family, or launch a business that breaks the mold, you will face your own wave of skepticism. People fear what they don’t understand. Arnold’s response is a masterclass in how to handle it. He never wavered, he never embellished, and he stuck meticulously to what he saw, not what he believed.

- Report, Don’t Interpret: Arnold described the objects’ shape, speed, and movement. He didn’t claim they were alien spaceships. He reported the data. When you present a new idea, stick to the facts, the potential, and the plan. Let others draw their own conclusions. Getting into a debate about beliefs is a losing game.

- Find Your Allies: While many scoffed, others came forward with their own sightings. Arnold wasn’t alone for long. When you’re pushing a new frontier, you must find the other people who see the same possibility. They are your confirmation and your support system.

- Don’t Get Defensive: Ridicule is designed to make you emotional, and when you’re emotional, you lose credibility. Stay calm. Let the merits of your idea and, eventually, your results, do the talking.

- Maintain Your Credibility: Arnold’s reputation as a sober businessman was his greatest asset. In everything you do, your integrity is your shield. Guard it fiercely.

Your Personal Plan for Managing Doubters:

Your Personal Plan for Managing Doubters:

- Step 1: Write Your “Arnold Report.” Before presenting your new idea, write it down in the plainest, most factual language possible. What is the observation/opportunity? What is the data? What is the proposed action? This document becomes your anchor.

- Step 2: Build a “Witness Coalition.” Before going public with a big idea, test it with a small group of trusted, open-minded advisors. Get their feedback and build a small core of support before you face the wider world.

- Step 3: Focus on the “Flight Test.” Instead of endlessly arguing about your idea, create a small-scale pilot program or experiment to test it. A small, successful demonstration is infinitely more powerful than the most eloquent argument. Build a prototype of your “saucer.”

- Step 4: Reframe Skepticism as a Data Point. When someone pokes a hole in your idea, don’t see it as an attack. See it as valuable data. They’ve just shown you a weakness you need to patch. Thank them for the stress test.

Benefit Today: Learn to Fly Confidently into the Unknown

The flying saucer phenomenon thrust society into a conversation with the unknown. It was unsettling, exciting, and paradigm-shattering. Your own personal growth works the same way. The most transformative experiences in your life will happen when you voluntarily fly out of your comfortable, mapped territory and into the vast, unknown sky. Arnold didn’t know what he was looking at, but he didn’t turn back. He watched, he learned, and he flew onward.

- See Uncertainty as Opportunity: A mapped world has no room for discovery. Uncertainty is simply a blank space on the map where you can draw something new.

- Cultivate Calculated Risk-Taking: Arnold was a pilot; he understood risk. He didn’t do anything reckless. Embracing the unknown doesn’t mean being careless. It means taking well-considered leaps.

- Make Curiosity Your Co-Pilot: Let your curiosity guide you more than your fear. When you have a choice between the safe, known path and the uncertain but intriguing one, let curiosity break the tie.

- Your Comfort Zone is a Ceiling: You cannot grow and stay comfortable at the same time. Personal evolution requires you to fly at an altitude that makes you just a little bit nervous.

Your Personal Plan for Embracing the Unknown:

Your Personal Plan for Embracing the Unknown:

- Step 1: Define Your “Safety Altitude.” What is the minimum you need to feel secure (financially, emotionally)? Knowing you have a safety net makes taking risks far less terrifying. What’s your “parachute”?

- Step 2: Take One “Calculated Leap” a Month. This doesn’t have to be life-altering. It could be signing up for a class you know nothing about, volunteering for a project outside your skill set, or taking a solo weekend trip. The goal is to build your “unknown” muscle.

- Step 3: Reframe Your Language. Banish “I can’t” and “That’s impossible” from your vocabulary. Replace them with “How could I?” and “What would it take?” Language shapes reality.

- Step 4: Find Your Mount Rainier. What is the big, exciting, slightly scary thing on your horizon that you keep looking at but never fly toward? Make a commitment today to start banking in that direction.

On June 24, 1947, Kenneth Arnold saw something that changed the world. But the lesson isn’t about aliens or government conspiracies. It’s a deeply human story about what happens at the edge of perception. It’s a blueprint for how to see what others miss, how to stand by your vision in the face of doubt, and how to find the courage to fly toward the thrilling unknown. The most amazing things in your life are out there, right now, flying just beyond the edge of your sight. Look up.