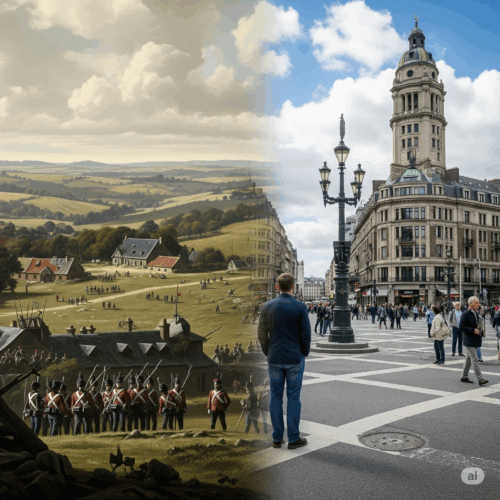

Part I: The Day the World Held Its Breath: The Field of Waterloo, June 18, 1815

Introduction: A Storm of Mud and Fate

The morning of June 18, 1815, dawned not with a glorious sunrise but with a miserable, persistent drizzle. For hours, a violent thunderstorm had lashed the rolling fields of Belgium, turning the rich farmland into a sodden quagmire. Nearly 200,000 soldiers from half a dozen nations shivered in the damp, their magnificent uniforms caked in mud, their stomachs empty, and their nerves frayed. They were waiting. Waiting for the ground to dry. Waiting for orders. Waiting for a battle that would, in a single, bloody day, decide the fate of Europe for the next century.

On one ridge stood the French army, commanded by the most formidable military mind in history: Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Having clawed his way back from exile on the island of Elba, he was risking everything on one last, desperate gamble to reclaim his empire. On the opposing ridge stood a patchwork army of British, Dutch, Belgian, and German troops under the command of a man who was Napoleon’s opposite in almost every way: the cool, aristocratic, and unflappable Duke of Wellington. This wasn’t just a clash of armies; it was a collision of philosophies. It was audacious genius versus methodical preparation, a final, epic confrontation between the man who had torn the old world apart and the man tasked with holding it together.

The phrase “to meet your Waterloo” has entered our language as a synonym for a final, crushing defeat. But this is a profound misunderstanding of what happened on that muddy field. Napoleon’s defeat was not a random stroke of bad luck. It was the inevitable collapse that occurs when a brilliant but flawed strategy, built on arrogance and assumption, smashes against a system designed to withstand it. The Battle of Waterloo is not a story about failure; it is a masterclass in how to prepare for, endure, and win the defining challenges of your life. It is a blueprint for victory.

The phrase “to meet your Waterloo” has entered our language as a synonym for a final, crushing defeat. But this is a profound misunderstanding of what happened on that muddy field. Napoleon’s defeat was not a random stroke of bad luck. It was the inevitable collapse that occurs when a brilliant but flawed strategy, built on arrogance and assumption, smashes against a system designed to withstand it. The Battle of Waterloo is not a story about failure; it is a masterclass in how to prepare for, endure, and win the defining challenges of your life. It is a blueprint for victory.

The Emperor’s Final Gambit: A Strategy of Desperate Genius

To understand Waterloo, you must understand the “Hundred Days” that preceded it. Less than a year earlier, Napoleon had been defeated and exiled. The old monarchy, under the deeply unpopular King Louis XVIII, was restored in France. The new regime quickly alienated the army by putting thousands of officers on half-pay and angered the populace by restoring the old aristocracy’s airs and graces. Sensing his opportunity, Napoleon escaped from Elba in March 1815 and landed in France. His return was a triumph of sheer charisma; the very troops sent to arrest him wept and flocked to his banner, and he marched into Paris without firing a shot.

But his throne was precarious. The great powers of Europe—Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia—immediately declared him an outlaw and formed the Seventh Coalition, mobilizing nearly a million men to crush him once and for all. Napoleon, with a hastily assembled army of around 200,000, was massively outnumbered. A defensive war was politically impossible. His only chance was to strike first, fast, and decisively. His strategy was a classic of his own design: divide and conquer. He would march into Belgium and attack the British and Prussian armies before they could unite, hoping a stunning victory would shatter the Coalition’s will and force them to the peace table. It was a strategy born of desperation, a high-stakes gamble that required a perfect execution and left no room for error. This immense pressure, the need for a single, knockout blow, would ultimately cloud his judgment and lead to his downfall.

The Duke’s Calculated Defense: A Masterclass in Risk Mitigation

The Duke of Wellington was no stranger to fighting the French, having battled them for years in Spain and Portugal. He was not a dazzling innovator like Napoleon, but a master of logistics, terrain, and defensive warfare. He knew he could not out-maneuver Napoleon in a dynamic, open battle. So he chose not to.

Instead, he meticulously prepared. He personally selected the battlefield at Mont-Saint-Jean, a site he had surveyed years before, recognizing its defensive strengths. The centerpiece of his plan was a low ridge, which gave his forces the advantage of high ground. Here, he deployed his most famous tactic: the “reverse slope” defense. He positioned the bulk of his army on the far side of the ridge, hidden from French view and, crucially, shielded from the devastating fire of Napoleon’s world-class artillery. With this single, brilliant move, Wellington neutralized one of his enemy’s greatest assets before the first shot was even fired.

He also understood the limitations of his own forces. His army was a multinational coalition, a mix of veteran British redcoats and inexperienced Dutch, Belgian, and German troops. He pragmatically integrated these units, pairing green soldiers with hardened veterans to bolster their resolve. But the absolute cornerstone of his entire strategy was an alliance. He had a pact with the Prussian commander, the fiery 72-year-old Marshal Gebhard von Blücher. They had agreed to support one another, and Wellington’s decision to stand and fight at Waterloo was entirely contingent on the promise that the Prussians would march to his aid.

He also understood the limitations of his own forces. His army was a multinational coalition, a mix of veteran British redcoats and inexperienced Dutch, Belgian, and German troops. He pragmatically integrated these units, pairing green soldiers with hardened veterans to bolster their resolve. But the absolute cornerstone of his entire strategy was an alliance. He had a pact with the Prussian commander, the fiery 72-year-old Marshal Gebhard von Blücher. They had agreed to support one another, and Wellington’s decision to stand and fight at Waterloo was entirely contingent on the promise that the Prussians would march to his aid.

Wellington’s approach was the antithesis of Napoleon’s. Where Napoleon relied on his personal genius to improvise a victory, Wellington relied on a system of meticulous preparation, risk mitigation, and unwavering trust in his allies. He wasn’t trying to be a better Napoleon; he was building a fortress designed to break him.

Part II: The Anatomy of a Defeat: A Cascade of Critical Errors

The Mud Trap: When Perfection Becomes the Enemy of Good

Napoleon was a master of artillery. He knew that to shatter Wellington’s lines quickly, he needed his cannons to be brutally effective. But on the morning of June 18, the ground was a sea of mud. This was a disaster for his plan. The soft earth would make it nearly impossible to maneuver the heavy guns, and worse, it would absorb the impact of the cannonballs, preventing them from skipping across the ground and maximizing casualties.

Faced with imperfect conditions, Napoleon made a fateful decision. Instead of adapting his plan, he decided to wait for the conditions to adapt to him. He delayed the start of the battle from the early morning until 11:30 AM, hoping the sun and wind would dry the ground. This delay was catastrophic. It gave Marshal Blücher’s Prussian army, defeated but not destroyed two days earlier, the crucial extra hours they needed to regroup and march towards Waterloo. In his quest for the perfect tactical advantage, Napoleon sacrificed his entire strategic position.

In a fascinating historical footnote, some scientists now believe this unseasonably violent weather may have been caused by the massive eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia two months prior. The theory suggests that electrostatically charged volcanic ash shot into the ionosphere, disrupting global weather patterns. While still debated, it adds a layer of beautiful chaos to the story—a distant cataclysm creating the local conditions for an empire’s fall.

The Bravest of the Brave, The Worst of Assumptions

Around 4:00 PM, after hours of brutal, grinding attacks, the French commander Marshal Michel Ney—known as “the bravest of the brave”—saw movement on the Allied ridge. He saw supply wagons and stretchers carrying the wounded to the rear and made a catastrophic assumption: Wellington’s army was breaking. He believed he was seeing a full-scale retreat.

Without verifying this information and without direct orders from Napoleon, Ney launched one of history’s most infamous cavalry charges. He hurled 5,000, and eventually nearly 10,000, of France’s elite horsemen at the Allied line. It was a magnificent, terrifying sight. But Wellington’s infantry was not retreating. They calmly formed defensive squares—four-sided formations of infantry with bayonets pointing outwards, creating bristling walls of steel that were virtually impenetrable to cavalry.

Again and again, the French cavalry charged with incredible courage, swirling around the unbreakable squares, but they could not break through. Unsupported by their own infantry or coordinated artillery, the attack was a glorious but bloody failure. It accomplished nothing and squandered the finest cavalry in Europe. Ney’s action was immense, but it wasn’t progress. It was energy without intelligence, a fatal mistake born from an unverified assumption.

Again and again, the French cavalry charged with incredible courage, swirling around the unbreakable squares, but they could not break through. Unsupported by their own infantry or coordinated artillery, the attack was a glorious but bloody failure. It accomplished nothing and squandered the finest cavalry in Europe. Ney’s action was immense, but it wasn’t progress. It was energy without intelligence, a fatal mistake born from an unverified assumption.

The Ghost Army: A Failure of Trust and Initiative

As the main battle raged, a significant portion of Napoleon’s army—33,000 men under Marshal Grouchy—was miles away. They were the “ghost army,” sent to pursue the Prussians after their earlier defeat. When the thunder of the cannons at Waterloo reached Grouchy’s position, his subordinate commanders begged him to abandon the pursuit and “march to the sound of the guns.”

Grouchy refused. A cautious and uninspired commander, he chose to rigidly adhere to his last written orders from Napoleon. He lacked the initiative to recognize that the strategic situation had changed and that his duty was now to support his emperor. This failure of initiative was mirrored by Napoleon’s own hesitation. When Ney’s infantry finally did capture the vital farmhouse of La Haye Sainte at the center of Wellington’s line and pleaded for a few battalions of reinforcements to deliver the final blow, Napoleon refused. Preoccupied by the first signs of the Prussians arriving on his flank, he would not commit his ultimate reserve, the elite Imperial Guard, until it was far too late.

The arrival of Blücher’s Prussians was the final nail in the coffin. They slammed into Napoleon’s right flank, forcing him to divert the Imperial Guard to hold the village of Plancenoit in a desperate rearguard action. This pressure, combined with Wellington’s final, decisive repulse of the last French attack, caused the entire French army to crack, collapse, and flee in a chaotic rout. The French command structure, built on the genius of one man and the rigid obedience of his followers, had proven too brittle. The Allied command, built on a pact of mutual trust, had proven resilient.

Part III: The Wellington Blueprint: Applying Battlefield Strategy to Your Life

Reframing Your ‘Waterloo’

We all face “Waterloo” moments. They are the critical tests in our careers, our relationships, and our personal projects where our strategies, preparations, and character are put to the ultimate test. These are the moments when a single presentation can define a career, a difficult conversation can save a relationship, or a crucial project can make or break a business. The goal is not to fear these moments, but to use the lessons of June 18, 1815, to ensure that we are the ones left standing on the ridge at the end of the day.

The difference between Napoleon’s defeat and Wellington’s victory came down to a few core principles, a mindset that can be applied directly to the challenges we face today.

| Strategic Principle | Napoleon’s Approach (The Path to Defeat) | Wellington’s Approach (The Blueprint for Victory) |

| Preparation vs. Improvisation | Relied on battlefield genius and a single, perfect plan. When conditions changed, the plan crumbled. | Meticulous, long-term preparation. Chose the ground in advance and designed a system to absorb predictable attacks. |

| Alliances & Trust | A top-down, brittle command structure that punished initiative (Grouchy) and lacked communication (Ney). | Built on a pact of mutual support. Trusted Blücher would honor his commitment, which was the cornerstone of the entire strategy. |

| Risk Management | An all-or-nothing gamble for a quick, decisive victory. High risk, high reward, but with no fallback plan. | Focused on risk mitigation. Protected his troops with the reverse slope and fought a defensive battle to minimize casualties until reinforcements arrived. |

| Dealing with Imperfection | Waited for perfect conditions (dry ground), losing critical time and allowing the strategic situation to worsen. | Fought with an imperfect, multinational army. He didn’t complain; he integrated them and created a plan that worked with what he had. |

| Information & Assumptions | Allowed his commanders (Ney) to act on unverified, catastrophic assumptions. Failed to adapt to new information (Prussian arrival) quickly enough. | Maintained situational awareness and based his defensive stance on the reliable intelligence that the Prussians were coming. |

A Five-Point Plan for Personal Victory: The Wellington Blueprint

- 1. Choose Your Ground: The Wellington Ridge Tactic.

Wellington didn’t fight Napoleon on Napoleon’s terms. He chose a battlefield that maximized his own strengths (defense) and neutralized Napoleon’s (artillery).

- Your Action Plan: In any project, negotiation, or conflict, consciously identify your “high ground.” What are your unique skills and unfair advantages? If you are a brilliant writer, frame the debate in a meticulously crafted memo. If you are a charismatic speaker, push for a live presentation. Don’t let your opponent choose the battlefield. Define the terrain and force them to come to you, where you are strongest.

- 2. Master the Reverse Slope: Protect Your Core Morale.

Wellington hid his main force from Napoleon’s cannons, preserving their physical strength and, just as importantly, their morale for the battle’s critical moments.

- Your Action Plan: Identify the sources of “artillery” in your own life—the constant bombardment of negativity, distraction, and stress. This could be endless social media scrolling, toxic colleagues, or your own inner critic. Build your own “reverse slope.” Set firm boundaries. Curate your information diet. Create non-negotiable routines (like exercise, meditation, or time in nature) that shield your mental and emotional energy. Your resilience is a finite and precious resource; guard it as fiercely as Wellington guarded his soldiers.

- 3. Secure Your ‘Prussian’ Alliance: Forge Unbreakable Support.

Wellington’s victory would have been impossible without Blücher’s Prussians. That alliance was not an accident; it was a pact secured long before the battle, built on a foundation of mutual trust and commitment.

- Your Action Plan: Map your personal coalition. Who are the people essential to your success—mentors, advocates, loyal peers, supportive family? Do not wait until you are in a crisis to find them. Invest in these relationships now. Be the kind of reliable, supportive ally that you need. Your network is not a list of contacts; it is your reinforcement army waiting in the wings.

- 4. Counter ‘Ney’s Charge’: A System for Stress-Testing Assumptions.

Marshal Ney’s heroic but disastrous charge was born from a single, fatal, and unverified assumption.

- Your Action Plan: Before you launch a major project, make a difficult decision, or commit significant resources (your “cavalry”), explicitly name your core assumptions. Ask yourself: “What must be true for this to be the right move?” Then, actively try to disprove those assumptions. Seek out dissenting opinions. Find someone to play devil’s advocate. A few minutes of scrutiny before you charge can prevent a massive, futile waste of energy.

- 5. Escape the ‘Mud Trap’: A Bias for Imperfect Action.

Napoleon’s delay, waiting for the mud to dry, cost him his empire. He waited for the perfect moment, and the opportunity vanished forever.

- Your Action Plan: Fight perfectionism, which is often just fear in disguise. For any task, define what “good enough” looks like, not what “perfect” looks like. It is almost always better to launch a project at 80% and iterate than to wait for a flawless 100% and miss your window. Momentum is a strategic asset. Get your cannons moving, even if the ground is a little muddy.

Part IV: Conclusion: History’s Greatest Lesson

The Battle of Waterloo teaches us that victory is rarely the product of solitary, spontaneous genius. It is the product of superior preparation, strategic patience, resilient alliances, and the courage to act in an imperfect world. Wellington won not because he was a greater military genius than Napoleon—he wasn’t—but because his system was more robust, more adaptable, and more grounded in reality than Napoleon’s.

The story of that day is more than just history. It is a timeless lesson in strategy and human nature. The next time you face a great challenge, remember the muddy fields of Waterloo. Don’t be the Emperor, staking everything on a single, flawless plan. Be the Duke. Choose your ground, protect your morale, trust your allies, check your assumptions, and have the courage to advance. History has given you the blueprint. The next move is yours.