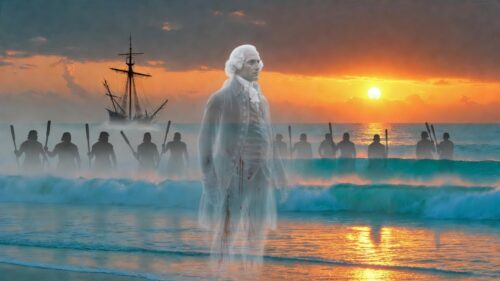

Picture this: It's February 14, 1779. The air in Kealakekua Bay is thick with the scent of plumeria and tension. Two worlds are about to smash into each other like a British frigate ramming a coral reef. On one side, the greatest explorer the Royal Navy has ever produced—Captain James Cook, the man who mapped more of the planet than anyone before him, the guy who turned the Pacific from a blank spot on the map into a British playground. On the other? A thousand Hawaiian warriors, feathers flying, clubs raised, convinced (or at least half-convinced) that this pale, gray-haired stranger might be their god Lono come back to party... or maybe just some pushy haole who overstayed his welcome. What happens next isn't just a footnote in exploration history. It's a masterclass in what happens when arrogance meets ancient protocol, when "I'm in charge here" collides with "this is *our* house, brah." Cook dies in the shallows, stabbed in the neck, clubbed senseless, his body dragged away to be ritually dismembered by the very people who'd once prostrated themselves at his feet. And yet, from that blood-soaked beach in Hawaii, we can pull out a survival manual so sharp it could slice through any modern mess you're facing—career implosion, relationship reef, personal storm. Stick with me. This 2,500-word deep dive into one of history's wildest "what the hell just happened" moments is 90% pure, pulse-pounding 18th-century drama. The last 10%? Your personalized, no-BS plan to weaponize it in 2026.

### The Man Who Charted the Unknown (And Thought He Could Chart People Too)

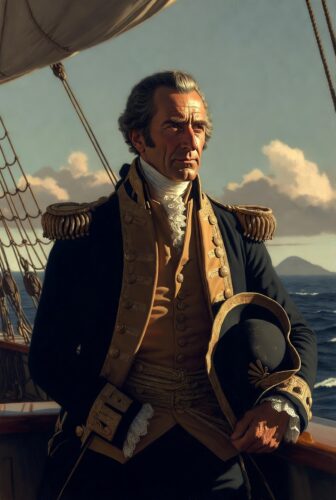

James Cook wasn't born to rule the waves. He was the son of a Scottish farm laborer in Yorkshire, apprenticed to a grocer at 13, then jumping ship (literally) to join the coal trade. By 27, he was a master mariner, but the big break came in 1755 when he enlisted in the Royal Navy as an able seaman. Smart move. Within seven years, he was charting the St. Lawrence River during the Seven Years' War, earning a reputation as the guy who could turn "impossible" into "done by teatime."

Fast-forward to 1768. The Royal Society taps him to lead the *Endeavour* to Tahiti for the Transit of Venus—a scientific flex to measure the solar system. Cook turns it into a three-year circumnavigation that maps New Zealand's entire coastline (no small feat) and Australia's east coast, claiming it for King George. He does it with zero scurvy deaths, thanks to his obsessive sauerkraut rations and fresh greens. The man is a logistics god.

Voyage two (1772-1775) is even crazier: he crosses the Antarctic Circle three times, proves there's no massive southern continent, and charts Tonga, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. By the time he's 47, Cook is a legend—Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted to captain, the toast of London drawing rooms. But the itch is still there. In 1776, at 47 (ancient for a sea dog), he takes command of the *Resolution* and *Discovery* for voyage three: find the Northwest Passage from the Pacific side. Spoiler: he doesn't. But he does "discover" Hawaii.

What happens next isn't just a footnote in exploration history. It's a masterclass in what happens when arrogance meets ancient protocol, when "I'm in charge here" collides with "this is *our* house, brah." Cook dies in the shallows, stabbed in the neck, clubbed senseless, his body dragged away to be ritually dismembered by the very people who'd once prostrated themselves at his feet. And yet, from that blood-soaked beach in Hawaii, we can pull out a survival manual so sharp it could slice through any modern mess you're facing—career implosion, relationship reef, personal storm. Stick with me. This 2,500-word deep dive into one of history's wildest "what the hell just happened" moments is 90% pure, pulse-pounding 18th-century drama. The last 10%? Your personalized, no-BS plan to weaponize it in 2026.

### The Man Who Charted the Unknown (And Thought He Could Chart People Too)

James Cook wasn't born to rule the waves. He was the son of a Scottish farm laborer in Yorkshire, apprenticed to a grocer at 13, then jumping ship (literally) to join the coal trade. By 27, he was a master mariner, but the big break came in 1755 when he enlisted in the Royal Navy as an able seaman. Smart move. Within seven years, he was charting the St. Lawrence River during the Seven Years' War, earning a reputation as the guy who could turn "impossible" into "done by teatime."

Fast-forward to 1768. The Royal Society taps him to lead the *Endeavour* to Tahiti for the Transit of Venus—a scientific flex to measure the solar system. Cook turns it into a three-year circumnavigation that maps New Zealand's entire coastline (no small feat) and Australia's east coast, claiming it for King George. He does it with zero scurvy deaths, thanks to his obsessive sauerkraut rations and fresh greens. The man is a logistics god.

Voyage two (1772-1775) is even crazier: he crosses the Antarctic Circle three times, proves there's no massive southern continent, and charts Tonga, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. By the time he's 47, Cook is a legend—Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted to captain, the toast of London drawing rooms. But the itch is still there. In 1776, at 47 (ancient for a sea dog), he takes command of the *Resolution* and *Discovery* for voyage three: find the Northwest Passage from the Pacific side. Spoiler: he doesn't. But he does "discover" Hawaii. January 18, 1778. The ships sight Oahu. Hawaiians paddle out in canoes, eyes wide at the floating fortresses with white sails and iron everything. Cook names them the Sandwich Islands after his patron, the Earl of Sandwich (yes, the sandwich guy). They trade nails for pigs, sex for nails—classic Pacific contact. Cook notes the Hawaiians are "the most civilized" he'd seen, but also thieves who could steal the shirt off your back while smiling. He leaves after a week, heads north to Alaska, fails at the Passage, and turns back south for repairs.

February 1779. Back to the Big Island. But this time? Different vibe.

### Makahiki Magic: When Cook Arrived as (Maybe) a God

Hawaiian society in 1779 was no primitive backwater. It was a sophisticated chiefdom with aliʻi (nobles), kahuna (priests), strict kapu (taboos), and a calendar tied to the gods. The Makahiki festival—running roughly November to February—was sacred to Lono, the god of fertility, rain, peace, and agriculture. No war. No heavy kapu. Just feasting, games, tribute to the chiefs, and processions carrying Lono's symbol: a tall pole with white kapa cloth and bird feathers, looking suspiciously like a ship's mast with sails.

Cook's *Resolution* limps into Kealakekua Bay on January 17, 1779—peak Makahiki. Ten thousand Hawaiians line the cliffs, chanting. Canoes swarm the ships. Priests from the heiau (temple) at Hikiau lead Cook ashore. They drape him in red kapa, chant "Lono!" and prostrate. Cook, ever the scientist, goes along with the ceremony, sketching the idols. The crew gets the royal treatment: unlimited pork, women, yams. Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the aliʻi nui (high chief) of the island, paddles out on February 25 (wait, no—January 25 in some accounts, but the timeline blurs in the logs). He and Cook exchange names. The chief gives Cook his feathered cloak. They rub noses. It's basically a divine bromance.

January 18, 1778. The ships sight Oahu. Hawaiians paddle out in canoes, eyes wide at the floating fortresses with white sails and iron everything. Cook names them the Sandwich Islands after his patron, the Earl of Sandwich (yes, the sandwich guy). They trade nails for pigs, sex for nails—classic Pacific contact. Cook notes the Hawaiians are "the most civilized" he'd seen, but also thieves who could steal the shirt off your back while smiling. He leaves after a week, heads north to Alaska, fails at the Passage, and turns back south for repairs.

February 1779. Back to the Big Island. But this time? Different vibe.

### Makahiki Magic: When Cook Arrived as (Maybe) a God

Hawaiian society in 1779 was no primitive backwater. It was a sophisticated chiefdom with aliʻi (nobles), kahuna (priests), strict kapu (taboos), and a calendar tied to the gods. The Makahiki festival—running roughly November to February—was sacred to Lono, the god of fertility, rain, peace, and agriculture. No war. No heavy kapu. Just feasting, games, tribute to the chiefs, and processions carrying Lono's symbol: a tall pole with white kapa cloth and bird feathers, looking suspiciously like a ship's mast with sails.

Cook's *Resolution* limps into Kealakekua Bay on January 17, 1779—peak Makahiki. Ten thousand Hawaiians line the cliffs, chanting. Canoes swarm the ships. Priests from the heiau (temple) at Hikiau lead Cook ashore. They drape him in red kapa, chant "Lono!" and prostrate. Cook, ever the scientist, goes along with the ceremony, sketching the idols. The crew gets the royal treatment: unlimited pork, women, yams. Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the aliʻi nui (high chief) of the island, paddles out on February 25 (wait, no—January 25 in some accounts, but the timeline blurs in the logs). He and Cook exchange names. The chief gives Cook his feathered cloak. They rub noses. It's basically a divine bromance. For weeks, it's paradise. But cracks appear. A sailor dies and is buried at the heiau—Hawaiians are horrified; the dead don't belong there. British sailors start dismantling the temple fence for firewood. Priests are pissed. Theft spikes—Hawaiians see European goods as fair game in the Lono spirit. Cook, usually patient, starts flogging thieves. A chief named Palea gets clocked with an oar after a canoe dispute. Tensions simmer.

Makahiki ends. The war god Kū takes over. The ships sail February 4. Then disaster: a storm snaps the *Resolution*'s foremast. They limp back to Kealakekua on February 11. No welcome this time. The bay is under kapu. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is grumpy. "Why you back, Lono? Party's over."

### The Fatal Theft and the Worst Decision in Exploration History

February 13-14. The *Discovery*'s large cutter—the ship's workhorse boat—vanishes overnight. Cook is livid. This isn't some trinket; it's critical gear. His solution? The same one that worked in Tonga and Tahiti: take the king hostage until it's returned.

At dawn on the 14th, Cook loads 10 Royal Marines into the pinnace and launch. He rows to Kaʻawaloa, the chiefs' village on the north shore. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is still in bed. Cook wakes him politely, explains the situation, and suggests a little "visit" to the ship. The old chief, who's been friendly, agrees. His two young sons even scamper ahead to the boat.

But then the wives show up. Kānekapōlei, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's favorite, throws herself at his feet, wailing. Other chiefs surround him, chanting, offering coconut. The crowd swells to 2,000-3,000. Warriors in war mats (thick, spear-proof cloaks) and helmets appear, spears and daggers glinting. Stones start flying.

Cook senses the shift. He tells Lieutenant Molesworth Phillips, "We can never think of compelling him to go on board without killing a number of people." Smart words. Too late to heed them.

Across the bay, bad news travels fast: a lesser chief, Kalimu, has been shot dead by British sailors in a separate scuffle. The crowd erupts. A warrior lunges at Cook with a dagger. Cook fires birdshot—harmless against the war mat. The warrior laughs. Cook switches to ball and drops a man. Chaos.

The marines fire one volley. Then they're swarmed. Clubs rain down. Cook, pistol empty, turns to signal the boats to come closer. Big mistake. A warrior named Kanaʻina (or maybe Kuamoʻo in some accounts) clubs him from behind. Cook staggers, falls to one knee. Another man—possibly a chief named Noʻo—stabs him in the neck with an iron dagger the British themselves had traded.

For weeks, it's paradise. But cracks appear. A sailor dies and is buried at the heiau—Hawaiians are horrified; the dead don't belong there. British sailors start dismantling the temple fence for firewood. Priests are pissed. Theft spikes—Hawaiians see European goods as fair game in the Lono spirit. Cook, usually patient, starts flogging thieves. A chief named Palea gets clocked with an oar after a canoe dispute. Tensions simmer.

Makahiki ends. The war god Kū takes over. The ships sail February 4. Then disaster: a storm snaps the *Resolution*'s foremast. They limp back to Kealakekua on February 11. No welcome this time. The bay is under kapu. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is grumpy. "Why you back, Lono? Party's over."

### The Fatal Theft and the Worst Decision in Exploration History

February 13-14. The *Discovery*'s large cutter—the ship's workhorse boat—vanishes overnight. Cook is livid. This isn't some trinket; it's critical gear. His solution? The same one that worked in Tonga and Tahiti: take the king hostage until it's returned.

At dawn on the 14th, Cook loads 10 Royal Marines into the pinnace and launch. He rows to Kaʻawaloa, the chiefs' village on the north shore. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is still in bed. Cook wakes him politely, explains the situation, and suggests a little "visit" to the ship. The old chief, who's been friendly, agrees. His two young sons even scamper ahead to the boat.

But then the wives show up. Kānekapōlei, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's favorite, throws herself at his feet, wailing. Other chiefs surround him, chanting, offering coconut. The crowd swells to 2,000-3,000. Warriors in war mats (thick, spear-proof cloaks) and helmets appear, spears and daggers glinting. Stones start flying.

Cook senses the shift. He tells Lieutenant Molesworth Phillips, "We can never think of compelling him to go on board without killing a number of people." Smart words. Too late to heed them.

Across the bay, bad news travels fast: a lesser chief, Kalimu, has been shot dead by British sailors in a separate scuffle. The crowd erupts. A warrior lunges at Cook with a dagger. Cook fires birdshot—harmless against the war mat. The warrior laughs. Cook switches to ball and drops a man. Chaos.

The marines fire one volley. Then they're swarmed. Clubs rain down. Cook, pistol empty, turns to signal the boats to come closer. Big mistake. A warrior named Kanaʻina (or maybe Kuamoʻo in some accounts) clubs him from behind. Cook staggers, falls to one knee. Another man—possibly a chief named Noʻo—stabs him in the neck with an iron dagger the British themselves had traded. Eyewitness David Samwell, surgeon on the *Discovery*, captured the horror: "Captain Cook was then the only one remaining on the rock: he was observed making for the pinnace, holding his left hand against the back of his head, to guard it from the stones, and carrying his musket under the other arm... At last he advanced upon him unawares, and with a large club, or common stake, gave him a blow on the back of the head... The stroke seemed to have stunned Captain Cook: he staggered a few paces, then fell on his hand and one knee, and dropped his musket. As he was rising... another Indian stabbed him in the back of the neck with an iron dagger."

Cook topples into the surf. The Hawaiians drag him up the beach. More stabs, more clubs. Four marines die with him. The boats escape under cannon fire from the ships. By nightfall, Cook's body is gone—taken to the heiau, dismembered in ritual, bones cleaned and distributed as sacred relics to the chiefs. The British get back a few charred pieces: hands, skull, thigh bone. They bury what they can at sea with full honors.

Seventeen Hawaiians dead that day. A tragedy of misunderstandings, ego, and bad timing.

### The Aftermath: Regret, Recriminations, and a Legend Reborn

The crew is shattered. Captain Charles Clerke takes over, but he's dying of tuberculosis. They linger, skirmish more, then sail. In England, the news hits like a thunderclap. Cook is mourned as a hero. Statues go up. His journals become bestsellers. But the private logs tell a different story: Cook had grown irritable, quick to violence. William Bligh (yes, *that* Bligh of *Mutiny on the Bounty* fame) blamed the marines. Phillips blamed the boat crews. Everyone blamed everyone.

For the Hawaiians? Mixed. Some saw Cook's death as proof he wasn't Lono after all—gods don't bleed. Others whispered he *was* Lono, and his "death" was ascension. When missionaries arrived decades later, Hawaiians asked when Lono was coming back. Kalaniʻōpuʻu himself may have mourned in a cave. The islands unified under Kamehameha soon after, partly inspired by the British guns and discipline they'd seen.

Cook's legacy? He mapped 1/4 of the world's coastlines. Proved Antarctica was a continent. But that February 14? It humanized him. The invincible explorer reduced to a bleeding man in the surf, outmatched by people he'd underestimated.

### From Hawaiian Blood to Your Personal Revolution: The 2026 Playbook

Okay, history nerds, we've had our fun with the gore and glory. Now the payoff—the part where this 246-year-old clusterfuck becomes your unfair advantage.

Cook's death wasn't random bad luck. It was a textbook failure of *assumption*. He assumed his rules applied everywhere. He assumed force was always the shortcut. He assumed the "natives" would fold like they had before. Boom—dead in paradise.

You? You're not exploring the Pacific, but you're navigating your own uncharted waters every damn day: that toxic job, the stalled side hustle, the relationship that's circling the drain, the health goal you keep "almost" hitting. The same traps that got Cook can sink you. Here's how to flip the script, with hyper-specific, actionable bullets and a 30-day plan that turns "oh shit" into "watch this."

**The 7 Deadly Assumptions (and How to Assassinate Them)**

- **Assumption #1: "My way has always worked before."** Cook's hostage playbook succeeded in Polynesia... until it didn't. *Your move:* Audit your "proven" strategies quarterly. Pick one habit (email at 7am? Cold-calling leads?) and run a 48-hour experiment forcing the opposite. Example: If you're a night owl forcing 5am routines because "successful people do it," switch to 10pm-6am for a week and track output. Cook ignored the Makahiki calendar shift. You ignore your own energy calendar at your peril.

- **Assumption #2: "They'll respect my authority because I'm the expert."** Cook waltzed in like he owned the bay. The Hawaiians saw a guest who'd forgotten the house rules. *Your move:* In every high-stakes meeting or negotiation this month, lead with *their* protocol first. Sales call? Start with "What's one thing keeping you up at night about [their industry]?" Date night? Ask "What's one way I can make you feel more seen this week?" before pitching your agenda. Respect is currency—spend it first.

- **Assumption #3: "Escalation fixes theft."** A boat goes missing, so kidnap the king. Modern version: Employee ghosts a deadline, so you micromanage the whole team. *Your move:* Create a "Cool-Off Protocol." When something's stolen (time, trust, opportunity), wait 24 hours before acting. Use the time to ask: "What's the Hawaiian perspective here—what sacred rule did I unknowingly break?" Then respond with curiosity, not cannons.

- **Assumption #4: "I can read the room from the ship."** Cook stayed aboard while his men stirred the pot on shore. *Your move:* Get in the water. This month, for every major decision, spend one full day embedded with the "natives"—your team, your kids, your customers. Shadow a junior employee. Sit in on your partner's team meeting. Eat lunch in the break room. Data from the deck is fake news.

- **Assumption #5: "Backup will save me."** Cook signaled the boats... and they hesitated. *Your move:* Build "Signal Redundancy." Never rely on one rescue plan. In your life: Have a "Plan B" conversation with your partner/spouse/mentor *before* the crisis. "If I go radio silent for 48 hours on this project, here's exactly what I need you to do." Cook's crew second-guessed. Yours won't.

- **Assumption #6: "The gods are on my side."** Cook let the Lono myth inflate his ego. *Your move:* Kill the god complex. Start a "Mortality Journal." Every Sunday, write one paragraph: "If I died tomorrow, what would people say I got wrong?" Brutal. Liberating. Cook never asked the Hawaiians what they actually believed—he assumed.

- **Assumption #7: "Retreat is weakness."** Cook could've backed off when the crowd formed. He didn't. *Your move:* Master the "Graceful Pivot." When a situation turns hostile (argument, deal falling apart, health scare), have a pre-written exit line: "I hear you. Let's pause and reconvene when we're both calmer." Then *actually* do it. Pride is the real dagger in the neck.

Eyewitness David Samwell, surgeon on the *Discovery*, captured the horror: "Captain Cook was then the only one remaining on the rock: he was observed making for the pinnace, holding his left hand against the back of his head, to guard it from the stones, and carrying his musket under the other arm... At last he advanced upon him unawares, and with a large club, or common stake, gave him a blow on the back of the head... The stroke seemed to have stunned Captain Cook: he staggered a few paces, then fell on his hand and one knee, and dropped his musket. As he was rising... another Indian stabbed him in the back of the neck with an iron dagger."

Cook topples into the surf. The Hawaiians drag him up the beach. More stabs, more clubs. Four marines die with him. The boats escape under cannon fire from the ships. By nightfall, Cook's body is gone—taken to the heiau, dismembered in ritual, bones cleaned and distributed as sacred relics to the chiefs. The British get back a few charred pieces: hands, skull, thigh bone. They bury what they can at sea with full honors.

Seventeen Hawaiians dead that day. A tragedy of misunderstandings, ego, and bad timing.

### The Aftermath: Regret, Recriminations, and a Legend Reborn

The crew is shattered. Captain Charles Clerke takes over, but he's dying of tuberculosis. They linger, skirmish more, then sail. In England, the news hits like a thunderclap. Cook is mourned as a hero. Statues go up. His journals become bestsellers. But the private logs tell a different story: Cook had grown irritable, quick to violence. William Bligh (yes, *that* Bligh of *Mutiny on the Bounty* fame) blamed the marines. Phillips blamed the boat crews. Everyone blamed everyone.

For the Hawaiians? Mixed. Some saw Cook's death as proof he wasn't Lono after all—gods don't bleed. Others whispered he *was* Lono, and his "death" was ascension. When missionaries arrived decades later, Hawaiians asked when Lono was coming back. Kalaniʻōpuʻu himself may have mourned in a cave. The islands unified under Kamehameha soon after, partly inspired by the British guns and discipline they'd seen.

Cook's legacy? He mapped 1/4 of the world's coastlines. Proved Antarctica was a continent. But that February 14? It humanized him. The invincible explorer reduced to a bleeding man in the surf, outmatched by people he'd underestimated.

### From Hawaiian Blood to Your Personal Revolution: The 2026 Playbook

Okay, history nerds, we've had our fun with the gore and glory. Now the payoff—the part where this 246-year-old clusterfuck becomes your unfair advantage.

Cook's death wasn't random bad luck. It was a textbook failure of *assumption*. He assumed his rules applied everywhere. He assumed force was always the shortcut. He assumed the "natives" would fold like they had before. Boom—dead in paradise.

You? You're not exploring the Pacific, but you're navigating your own uncharted waters every damn day: that toxic job, the stalled side hustle, the relationship that's circling the drain, the health goal you keep "almost" hitting. The same traps that got Cook can sink you. Here's how to flip the script, with hyper-specific, actionable bullets and a 30-day plan that turns "oh shit" into "watch this."

**The 7 Deadly Assumptions (and How to Assassinate Them)**

- **Assumption #1: "My way has always worked before."** Cook's hostage playbook succeeded in Polynesia... until it didn't. *Your move:* Audit your "proven" strategies quarterly. Pick one habit (email at 7am? Cold-calling leads?) and run a 48-hour experiment forcing the opposite. Example: If you're a night owl forcing 5am routines because "successful people do it," switch to 10pm-6am for a week and track output. Cook ignored the Makahiki calendar shift. You ignore your own energy calendar at your peril.

- **Assumption #2: "They'll respect my authority because I'm the expert."** Cook waltzed in like he owned the bay. The Hawaiians saw a guest who'd forgotten the house rules. *Your move:* In every high-stakes meeting or negotiation this month, lead with *their* protocol first. Sales call? Start with "What's one thing keeping you up at night about [their industry]?" Date night? Ask "What's one way I can make you feel more seen this week?" before pitching your agenda. Respect is currency—spend it first.

- **Assumption #3: "Escalation fixes theft."** A boat goes missing, so kidnap the king. Modern version: Employee ghosts a deadline, so you micromanage the whole team. *Your move:* Create a "Cool-Off Protocol." When something's stolen (time, trust, opportunity), wait 24 hours before acting. Use the time to ask: "What's the Hawaiian perspective here—what sacred rule did I unknowingly break?" Then respond with curiosity, not cannons.

- **Assumption #4: "I can read the room from the ship."** Cook stayed aboard while his men stirred the pot on shore. *Your move:* Get in the water. This month, for every major decision, spend one full day embedded with the "natives"—your team, your kids, your customers. Shadow a junior employee. Sit in on your partner's team meeting. Eat lunch in the break room. Data from the deck is fake news.

- **Assumption #5: "Backup will save me."** Cook signaled the boats... and they hesitated. *Your move:* Build "Signal Redundancy." Never rely on one rescue plan. In your life: Have a "Plan B" conversation with your partner/spouse/mentor *before* the crisis. "If I go radio silent for 48 hours on this project, here's exactly what I need you to do." Cook's crew second-guessed. Yours won't.

- **Assumption #6: "The gods are on my side."** Cook let the Lono myth inflate his ego. *Your move:* Kill the god complex. Start a "Mortality Journal." Every Sunday, write one paragraph: "If I died tomorrow, what would people say I got wrong?" Brutal. Liberating. Cook never asked the Hawaiians what they actually believed—he assumed.

- **Assumption #7: "Retreat is weakness."** Cook could've backed off when the crowd formed. He didn't. *Your move:* Master the "Graceful Pivot." When a situation turns hostile (argument, deal falling apart, health scare), have a pre-written exit line: "I hear you. Let's pause and reconvene when we're both calmer." Then *actually* do it. Pride is the real dagger in the neck. **Your 30-Day "Cook's Comeback" Plan – Zero Fluff, All Fire**

**Week 1: Map Your Kealakekua**

Day 1-3: List every "bay" in your life (career, health, relationships, money) and rate the "Makahiki vibe" (peaceful season) vs. "Kū season" (war mode). Be brutally honest.

Day 4-7: Pick one bay. Spend 30 minutes daily interviewing "natives" (people in it) about their rules. No defending yourself. Just listen and take notes.

**Week 2: Test Your Assumptions**

Run the 48-hour opposite experiment on one assumption from the list above. Track results in a Google Doc titled "What Cook Would've F*cked Up Here."

**Week 3: Build Your Marine Guard**

Identify your 3-5 "marines" (ride-or-die allies). Have the "If I get clubbed" conversation with each. Write the exact signals and backups. Practice once.

**Week 4: The Burial at Sea**

On day 28, write the obituary of your old self—the one who assumes, escalates, and dies in the surf. Burn it (safely). Day 29-30: Launch one "Lono return"—a bold, respectful move in that bay you mapped, but this time with all the new protocols.

Do this, and by March 2026, you'll move through life like Cook *should* have: curious, humble, lethal when it counts—but never stupid.

Captain Cook didn't die because he was weak. He died because he forgot that every paradise has its own gods, its own calendar, its own daggers hidden in cloaks of hospitality. You don't have to. The same ocean that swallowed him can carry you to shores he never imagined.

Now go. The bay is waiting. Just remember: when the stones start flying, don't reach for the pistol. Reach for the question.

What sacred rule did I miss?

And then? Pivot like your life depends on it.

Because sometimes... it does.

**Your 30-Day "Cook's Comeback" Plan – Zero Fluff, All Fire**

**Week 1: Map Your Kealakekua**

Day 1-3: List every "bay" in your life (career, health, relationships, money) and rate the "Makahiki vibe" (peaceful season) vs. "Kū season" (war mode). Be brutally honest.

Day 4-7: Pick one bay. Spend 30 minutes daily interviewing "natives" (people in it) about their rules. No defending yourself. Just listen and take notes.

**Week 2: Test Your Assumptions**

Run the 48-hour opposite experiment on one assumption from the list above. Track results in a Google Doc titled "What Cook Would've F*cked Up Here."

**Week 3: Build Your Marine Guard**

Identify your 3-5 "marines" (ride-or-die allies). Have the "If I get clubbed" conversation with each. Write the exact signals and backups. Practice once.

**Week 4: The Burial at Sea**

On day 28, write the obituary of your old self—the one who assumes, escalates, and dies in the surf. Burn it (safely). Day 29-30: Launch one "Lono return"—a bold, respectful move in that bay you mapped, but this time with all the new protocols.

Do this, and by March 2026, you'll move through life like Cook *should* have: curious, humble, lethal when it counts—but never stupid.

Captain Cook didn't die because he was weak. He died because he forgot that every paradise has its own gods, its own calendar, its own daggers hidden in cloaks of hospitality. You don't have to. The same ocean that swallowed him can carry you to shores he never imagined.

Now go. The bay is waiting. Just remember: when the stones start flying, don't reach for the pistol. Reach for the question.

What sacred rule did I miss?

And then? Pivot like your life depends on it.

Because sometimes... it does.

What happens next isn't just a footnote in exploration history. It's a masterclass in what happens when arrogance meets ancient protocol, when "I'm in charge here" collides with "this is *our* house, brah." Cook dies in the shallows, stabbed in the neck, clubbed senseless, his body dragged away to be ritually dismembered by the very people who'd once prostrated themselves at his feet. And yet, from that blood-soaked beach in Hawaii, we can pull out a survival manual so sharp it could slice through any modern mess you're facing—career implosion, relationship reef, personal storm. Stick with me. This 2,500-word deep dive into one of history's wildest "what the hell just happened" moments is 90% pure, pulse-pounding 18th-century drama. The last 10%? Your personalized, no-BS plan to weaponize it in 2026. ### The Man Who Charted the Unknown (And Thought He Could Chart People Too) James Cook wasn't born to rule the waves. He was the son of a Scottish farm laborer in Yorkshire, apprenticed to a grocer at 13, then jumping ship (literally) to join the coal trade. By 27, he was a master mariner, but the big break came in 1755 when he enlisted in the Royal Navy as an able seaman. Smart move. Within seven years, he was charting the St. Lawrence River during the Seven Years' War, earning a reputation as the guy who could turn "impossible" into "done by teatime." Fast-forward to 1768. The Royal Society taps him to lead the *Endeavour* to Tahiti for the Transit of Venus—a scientific flex to measure the solar system. Cook turns it into a three-year circumnavigation that maps New Zealand's entire coastline (no small feat) and Australia's east coast, claiming it for King George. He does it with zero scurvy deaths, thanks to his obsessive sauerkraut rations and fresh greens. The man is a logistics god. Voyage two (1772-1775) is even crazier: he crosses the Antarctic Circle three times, proves there's no massive southern continent, and charts Tonga, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. By the time he's 47, Cook is a legend—Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted to captain, the toast of London drawing rooms. But the itch is still there. In 1776, at 47 (ancient for a sea dog), he takes command of the *Resolution* and *Discovery* for voyage three: find the Northwest Passage from the Pacific side. Spoiler: he doesn't. But he does "discover" Hawaii.

January 18, 1778. The ships sight Oahu. Hawaiians paddle out in canoes, eyes wide at the floating fortresses with white sails and iron everything. Cook names them the Sandwich Islands after his patron, the Earl of Sandwich (yes, the sandwich guy). They trade nails for pigs, sex for nails—classic Pacific contact. Cook notes the Hawaiians are "the most civilized" he'd seen, but also thieves who could steal the shirt off your back while smiling. He leaves after a week, heads north to Alaska, fails at the Passage, and turns back south for repairs. February 1779. Back to the Big Island. But this time? Different vibe. ### Makahiki Magic: When Cook Arrived as (Maybe) a God Hawaiian society in 1779 was no primitive backwater. It was a sophisticated chiefdom with aliʻi (nobles), kahuna (priests), strict kapu (taboos), and a calendar tied to the gods. The Makahiki festival—running roughly November to February—was sacred to Lono, the god of fertility, rain, peace, and agriculture. No war. No heavy kapu. Just feasting, games, tribute to the chiefs, and processions carrying Lono's symbol: a tall pole with white kapa cloth and bird feathers, looking suspiciously like a ship's mast with sails. Cook's *Resolution* limps into Kealakekua Bay on January 17, 1779—peak Makahiki. Ten thousand Hawaiians line the cliffs, chanting. Canoes swarm the ships. Priests from the heiau (temple) at Hikiau lead Cook ashore. They drape him in red kapa, chant "Lono!" and prostrate. Cook, ever the scientist, goes along with the ceremony, sketching the idols. The crew gets the royal treatment: unlimited pork, women, yams. Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the aliʻi nui (high chief) of the island, paddles out on February 25 (wait, no—January 25 in some accounts, but the timeline blurs in the logs). He and Cook exchange names. The chief gives Cook his feathered cloak. They rub noses. It's basically a divine bromance.

For weeks, it's paradise. But cracks appear. A sailor dies and is buried at the heiau—Hawaiians are horrified; the dead don't belong there. British sailors start dismantling the temple fence for firewood. Priests are pissed. Theft spikes—Hawaiians see European goods as fair game in the Lono spirit. Cook, usually patient, starts flogging thieves. A chief named Palea gets clocked with an oar after a canoe dispute. Tensions simmer. Makahiki ends. The war god Kū takes over. The ships sail February 4. Then disaster: a storm snaps the *Resolution*'s foremast. They limp back to Kealakekua on February 11. No welcome this time. The bay is under kapu. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is grumpy. "Why you back, Lono? Party's over." ### The Fatal Theft and the Worst Decision in Exploration History February 13-14. The *Discovery*'s large cutter—the ship's workhorse boat—vanishes overnight. Cook is livid. This isn't some trinket; it's critical gear. His solution? The same one that worked in Tonga and Tahiti: take the king hostage until it's returned. At dawn on the 14th, Cook loads 10 Royal Marines into the pinnace and launch. He rows to Kaʻawaloa, the chiefs' village on the north shore. Kalaniʻōpuʻu is still in bed. Cook wakes him politely, explains the situation, and suggests a little "visit" to the ship. The old chief, who's been friendly, agrees. His two young sons even scamper ahead to the boat. But then the wives show up. Kānekapōlei, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's favorite, throws herself at his feet, wailing. Other chiefs surround him, chanting, offering coconut. The crowd swells to 2,000-3,000. Warriors in war mats (thick, spear-proof cloaks) and helmets appear, spears and daggers glinting. Stones start flying. Cook senses the shift. He tells Lieutenant Molesworth Phillips, "We can never think of compelling him to go on board without killing a number of people." Smart words. Too late to heed them. Across the bay, bad news travels fast: a lesser chief, Kalimu, has been shot dead by British sailors in a separate scuffle. The crowd erupts. A warrior lunges at Cook with a dagger. Cook fires birdshot—harmless against the war mat. The warrior laughs. Cook switches to ball and drops a man. Chaos. The marines fire one volley. Then they're swarmed. Clubs rain down. Cook, pistol empty, turns to signal the boats to come closer. Big mistake. A warrior named Kanaʻina (or maybe Kuamoʻo in some accounts) clubs him from behind. Cook staggers, falls to one knee. Another man—possibly a chief named Noʻo—stabs him in the neck with an iron dagger the British themselves had traded.

Eyewitness David Samwell, surgeon on the *Discovery*, captured the horror: "Captain Cook was then the only one remaining on the rock: he was observed making for the pinnace, holding his left hand against the back of his head, to guard it from the stones, and carrying his musket under the other arm... At last he advanced upon him unawares, and with a large club, or common stake, gave him a blow on the back of the head... The stroke seemed to have stunned Captain Cook: he staggered a few paces, then fell on his hand and one knee, and dropped his musket. As he was rising... another Indian stabbed him in the back of the neck with an iron dagger." Cook topples into the surf. The Hawaiians drag him up the beach. More stabs, more clubs. Four marines die with him. The boats escape under cannon fire from the ships. By nightfall, Cook's body is gone—taken to the heiau, dismembered in ritual, bones cleaned and distributed as sacred relics to the chiefs. The British get back a few charred pieces: hands, skull, thigh bone. They bury what they can at sea with full honors. Seventeen Hawaiians dead that day. A tragedy of misunderstandings, ego, and bad timing. ### The Aftermath: Regret, Recriminations, and a Legend Reborn The crew is shattered. Captain Charles Clerke takes over, but he's dying of tuberculosis. They linger, skirmish more, then sail. In England, the news hits like a thunderclap. Cook is mourned as a hero. Statues go up. His journals become bestsellers. But the private logs tell a different story: Cook had grown irritable, quick to violence. William Bligh (yes, *that* Bligh of *Mutiny on the Bounty* fame) blamed the marines. Phillips blamed the boat crews. Everyone blamed everyone. For the Hawaiians? Mixed. Some saw Cook's death as proof he wasn't Lono after all—gods don't bleed. Others whispered he *was* Lono, and his "death" was ascension. When missionaries arrived decades later, Hawaiians asked when Lono was coming back. Kalaniʻōpuʻu himself may have mourned in a cave. The islands unified under Kamehameha soon after, partly inspired by the British guns and discipline they'd seen. Cook's legacy? He mapped 1/4 of the world's coastlines. Proved Antarctica was a continent. But that February 14? It humanized him. The invincible explorer reduced to a bleeding man in the surf, outmatched by people he'd underestimated. ### From Hawaiian Blood to Your Personal Revolution: The 2026 Playbook Okay, history nerds, we've had our fun with the gore and glory. Now the payoff—the part where this 246-year-old clusterfuck becomes your unfair advantage. Cook's death wasn't random bad luck. It was a textbook failure of *assumption*. He assumed his rules applied everywhere. He assumed force was always the shortcut. He assumed the "natives" would fold like they had before. Boom—dead in paradise. You? You're not exploring the Pacific, but you're navigating your own uncharted waters every damn day: that toxic job, the stalled side hustle, the relationship that's circling the drain, the health goal you keep "almost" hitting. The same traps that got Cook can sink you. Here's how to flip the script, with hyper-specific, actionable bullets and a 30-day plan that turns "oh shit" into "watch this." **The 7 Deadly Assumptions (and How to Assassinate Them)** - **Assumption #1: "My way has always worked before."** Cook's hostage playbook succeeded in Polynesia... until it didn't. *Your move:* Audit your "proven" strategies quarterly. Pick one habit (email at 7am? Cold-calling leads?) and run a 48-hour experiment forcing the opposite. Example: If you're a night owl forcing 5am routines because "successful people do it," switch to 10pm-6am for a week and track output. Cook ignored the Makahiki calendar shift. You ignore your own energy calendar at your peril. - **Assumption #2: "They'll respect my authority because I'm the expert."** Cook waltzed in like he owned the bay. The Hawaiians saw a guest who'd forgotten the house rules. *Your move:* In every high-stakes meeting or negotiation this month, lead with *their* protocol first. Sales call? Start with "What's one thing keeping you up at night about [their industry]?" Date night? Ask "What's one way I can make you feel more seen this week?" before pitching your agenda. Respect is currency—spend it first. - **Assumption #3: "Escalation fixes theft."** A boat goes missing, so kidnap the king. Modern version: Employee ghosts a deadline, so you micromanage the whole team. *Your move:* Create a "Cool-Off Protocol." When something's stolen (time, trust, opportunity), wait 24 hours before acting. Use the time to ask: "What's the Hawaiian perspective here—what sacred rule did I unknowingly break?" Then respond with curiosity, not cannons. - **Assumption #4: "I can read the room from the ship."** Cook stayed aboard while his men stirred the pot on shore. *Your move:* Get in the water. This month, for every major decision, spend one full day embedded with the "natives"—your team, your kids, your customers. Shadow a junior employee. Sit in on your partner's team meeting. Eat lunch in the break room. Data from the deck is fake news. - **Assumption #5: "Backup will save me."** Cook signaled the boats... and they hesitated. *Your move:* Build "Signal Redundancy." Never rely on one rescue plan. In your life: Have a "Plan B" conversation with your partner/spouse/mentor *before* the crisis. "If I go radio silent for 48 hours on this project, here's exactly what I need you to do." Cook's crew second-guessed. Yours won't. - **Assumption #6: "The gods are on my side."** Cook let the Lono myth inflate his ego. *Your move:* Kill the god complex. Start a "Mortality Journal." Every Sunday, write one paragraph: "If I died tomorrow, what would people say I got wrong?" Brutal. Liberating. Cook never asked the Hawaiians what they actually believed—he assumed. - **Assumption #7: "Retreat is weakness."** Cook could've backed off when the crowd formed. He didn't. *Your move:* Master the "Graceful Pivot." When a situation turns hostile (argument, deal falling apart, health scare), have a pre-written exit line: "I hear you. Let's pause and reconvene when we're both calmer." Then *actually* do it. Pride is the real dagger in the neck.

**Your 30-Day "Cook's Comeback" Plan – Zero Fluff, All Fire** **Week 1: Map Your Kealakekua** Day 1-3: List every "bay" in your life (career, health, relationships, money) and rate the "Makahiki vibe" (peaceful season) vs. "Kū season" (war mode). Be brutally honest. Day 4-7: Pick one bay. Spend 30 minutes daily interviewing "natives" (people in it) about their rules. No defending yourself. Just listen and take notes. **Week 2: Test Your Assumptions** Run the 48-hour opposite experiment on one assumption from the list above. Track results in a Google Doc titled "What Cook Would've F*cked Up Here." **Week 3: Build Your Marine Guard** Identify your 3-5 "marines" (ride-or-die allies). Have the "If I get clubbed" conversation with each. Write the exact signals and backups. Practice once. **Week 4: The Burial at Sea** On day 28, write the obituary of your old self—the one who assumes, escalates, and dies in the surf. Burn it (safely). Day 29-30: Launch one "Lono return"—a bold, respectful move in that bay you mapped, but this time with all the new protocols. Do this, and by March 2026, you'll move through life like Cook *should* have: curious, humble, lethal when it counts—but never stupid. Captain Cook didn't die because he was weak. He died because he forgot that every paradise has its own gods, its own calendar, its own daggers hidden in cloaks of hospitality. You don't have to. The same ocean that swallowed him can carry you to shores he never imagined. Now go. The bay is waiting. Just remember: when the stones start flying, don't reach for the pistol. Reach for the question. What sacred rule did I miss? And then? Pivot like your life depends on it. Because sometimes... it does.