Picture this: It is February 11, 1144, in the ancient hilltop city of Segovia, high on the meseta of central Spain. Snow dusts the famous Roman aqueduct that has stood for over a thousand years, carrying water from the mountains like a stone serpent frozen in mid-slither. In a modest chamber lit by tallow candles and a brazier, an English cleric named Robert of Chester sets down his quill. He has just finished copying the final words of a manuscript he translated from Arabic into Latin. The colophon he adds is precise, almost defiant in its specificity: completed on the 11th day of February in the year of our Lord 1144.

He has no idea—no earthly clue—that this single act, this quiet transfer of ink from one language to another, will ignite a firestorm of curiosity, fraud, genius, and genuine discovery that will burn across Europe for the next seven centuries. This book, the *Liber de compositione alchemiae* (The Book of the Composition of Alchemy), is the first full alchemical treatise to reach the Latin West. Before Robert, Europeans had vague rumors of “Arabic sorcery” involving metals and elixirs. After him, kings, monks, scholars, and charlatans would chase the dream of transmutation with a fervor that blended the sacred and the ridiculous. This is not the story of a flashy battle or a famous coronation. It is the story of a translator in a borderland city, hunched over his desk while the Reconquista rumbled in the distance. It is a tale of cultural theft in the best possible sense—stealing knowledge across enemy lines—and it changed the trajectory of Western science more profoundly than most cannonades or coronations ever did. And by the end of this long ramble through the dusty corridors of the 12th century, you will see exactly how the spirit of that February day can become your own personal laboratory for turning the base metal of ordinary life into something far more valuable.

### The World That Needed a Spark

To understand why Robert’s translation mattered so much, you must first understand how intellectually starved Latin Europe was in the early 12th century. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed nearly 700 years earlier. What remained was a patchwork of feudal kingdoms, monasteries preserving fragments of classical learning, and a Church that was often more concerned with orthodoxy than experimentation. Greek texts survived mostly in Arabic translations made by scholars in Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba during the Islamic Golden Age. The great libraries of the Caliphate had safeguarded Aristotle, Plato, Galen, and the Hermetic writings, then improved upon them with original research in mathematics, optics, medicine, and—yes—alchemy.

Alchemy in the Islamic world was never the cartoonish gold-making scam it later became in the popular imagination. It was a sophisticated philosophical and practical discipline. Thinkers like Jabir ibn Hayyan (known to the Latins as Geber, fl. late 8th–early 9th century) developed an experimental method centuries before the so-called Scientific Revolution. Jabir emphasized repeatable processes, laboratory apparatus (alembics, stills, furnaces), and a theory that all metals were composed of two principles: sulfur (the fiery, combustible spirit) and mercury (the fluid, metallic body). By purifying and recombining these principles in the correct ratios, one could theoretically transmute base metals into noble ones or create the elixir of life.

This is not the story of a flashy battle or a famous coronation. It is the story of a translator in a borderland city, hunched over his desk while the Reconquista rumbled in the distance. It is a tale of cultural theft in the best possible sense—stealing knowledge across enemy lines—and it changed the trajectory of Western science more profoundly than most cannonades or coronations ever did. And by the end of this long ramble through the dusty corridors of the 12th century, you will see exactly how the spirit of that February day can become your own personal laboratory for turning the base metal of ordinary life into something far more valuable.

### The World That Needed a Spark

To understand why Robert’s translation mattered so much, you must first understand how intellectually starved Latin Europe was in the early 12th century. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed nearly 700 years earlier. What remained was a patchwork of feudal kingdoms, monasteries preserving fragments of classical learning, and a Church that was often more concerned with orthodoxy than experimentation. Greek texts survived mostly in Arabic translations made by scholars in Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba during the Islamic Golden Age. The great libraries of the Caliphate had safeguarded Aristotle, Plato, Galen, and the Hermetic writings, then improved upon them with original research in mathematics, optics, medicine, and—yes—alchemy.

Alchemy in the Islamic world was never the cartoonish gold-making scam it later became in the popular imagination. It was a sophisticated philosophical and practical discipline. Thinkers like Jabir ibn Hayyan (known to the Latins as Geber, fl. late 8th–early 9th century) developed an experimental method centuries before the so-called Scientific Revolution. Jabir emphasized repeatable processes, laboratory apparatus (alembics, stills, furnaces), and a theory that all metals were composed of two principles: sulfur (the fiery, combustible spirit) and mercury (the fluid, metallic body). By purifying and recombining these principles in the correct ratios, one could theoretically transmute base metals into noble ones or create the elixir of life. Jabir’s enormous corpus—much of it probably written by later followers in his school—stressed balance, the four elements of Aristotle (earth, air, fire, water) modified by the Islamic emphasis on qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry), and a spiritual dimension: the alchemist must purify his own soul to succeed in purifying matter. This was serious philosophy dressed in the language of the laboratory.

By the 12th century, Christian Europe was waking up to this treasure trove. The Reconquista had turned Spain into a porous frontier. Cities like Toledo, Barcelona, and Segovia became magnets for ambitious scholars willing to learn Arabic from Muslim and Jewish tutors. These men—often clerics with a taste for the forbidden or the useful—formed what historians now call the “Toledo School of Translators,” though the work happened in many places. They translated everything: Ptolemy’s astronomy, Avicenna’s medicine, Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra (which gave us the word “algorithm”), and, thanks to Robert, the secrets of alchemy.

### Enter Robert of Chester, the Unlikely Pioneer

We know frustratingly little about Robert the man. He was English, probably from the northwest (hence “of Chester”). By the 1140s he was in Spain, part of a loose network of translators that included the remarkable Hermann of Carinthia (also called Hermann the Dalmatian), a colorful character who roamed from the Pyrenees to the Ebro River in search of knowledge. Robert and Hermann seem to have collaborated or at least inspired each other. Robert also translated Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra in 1145—the first Latin version of that groundbreaking text—and astronomical works. He may later have become archdeacon of Pamplona. But his most explosive contribution came on that cold February day in Segovia.

Why Segovia? The city sat in the Kingdom of Castile, strategically located on the route between the Christian north and the Muslim south. Its Roman aqueduct still functioned, a daily reminder of lost grandeur that perhaps inspired men like Robert to recover ancient wisdom. The atmosphere was one of pragmatic curiosity rather than pure scholarship. Christian rulers needed administrative knowledge, medical expertise, and—let’s be honest—any technological edge they could get in their long war against the Almoravids and later Almohads.

Robert worked from an Arabic original now usually identified as *Masāʾil Khālid li-Maryānus al-rāhib* (The Questions of Khalid to the Monk Maryanus) or a text from the Jabirian corpus. The Latin title he gave it—*Liber de compositione alchemiae*—sounds dry, but the content is anything but. It is framed as a dramatic dialogue between a Christian hermit named Morienus (or Maryanus) and the Umayyad prince Khalid ibn Yazid.

### The Legend Within the Book: Morienus and Khalid

The story is pure medieval storytelling gold. Khalid ibn Yazid was a real historical figure, a prince of the Umayyad Caliphate in the late 7th century. After the dynasty’s bloody succession struggles, he supposedly retired from politics and devoted himself to learning. Legend says he became the first Muslim to seriously pursue alchemy. He searched far and wide until he found Morienus, a Christian hermit living in the mountains outside Alexandria or perhaps Damascus, who had inherited the true art from the ancient sages.

Khalid, being a prince, arrives with pomp and offers riches. Morienus, being a proper ascetic master, tests him mercilessly. He demands that Khalid abandon his worldly power, live simply, and prove his sincerity. Only then does the hermit reveal the secrets. The text includes practical instructions—how to prepare the “philosophical mercury,” the stages of the Great Work (nigredo, albedo, rubedo—the blackening, whitening, and reddening), the use of the “green lion” (a symbolic and sometimes literal substance, often linked to vitriol or antimony compounds that devour base metals), and the ultimate goal: the philosopher’s stone that transmutes and heals.

Jabir’s enormous corpus—much of it probably written by later followers in his school—stressed balance, the four elements of Aristotle (earth, air, fire, water) modified by the Islamic emphasis on qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry), and a spiritual dimension: the alchemist must purify his own soul to succeed in purifying matter. This was serious philosophy dressed in the language of the laboratory.

By the 12th century, Christian Europe was waking up to this treasure trove. The Reconquista had turned Spain into a porous frontier. Cities like Toledo, Barcelona, and Segovia became magnets for ambitious scholars willing to learn Arabic from Muslim and Jewish tutors. These men—often clerics with a taste for the forbidden or the useful—formed what historians now call the “Toledo School of Translators,” though the work happened in many places. They translated everything: Ptolemy’s astronomy, Avicenna’s medicine, Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra (which gave us the word “algorithm”), and, thanks to Robert, the secrets of alchemy.

### Enter Robert of Chester, the Unlikely Pioneer

We know frustratingly little about Robert the man. He was English, probably from the northwest (hence “of Chester”). By the 1140s he was in Spain, part of a loose network of translators that included the remarkable Hermann of Carinthia (also called Hermann the Dalmatian), a colorful character who roamed from the Pyrenees to the Ebro River in search of knowledge. Robert and Hermann seem to have collaborated or at least inspired each other. Robert also translated Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra in 1145—the first Latin version of that groundbreaking text—and astronomical works. He may later have become archdeacon of Pamplona. But his most explosive contribution came on that cold February day in Segovia.

Why Segovia? The city sat in the Kingdom of Castile, strategically located on the route between the Christian north and the Muslim south. Its Roman aqueduct still functioned, a daily reminder of lost grandeur that perhaps inspired men like Robert to recover ancient wisdom. The atmosphere was one of pragmatic curiosity rather than pure scholarship. Christian rulers needed administrative knowledge, medical expertise, and—let’s be honest—any technological edge they could get in their long war against the Almoravids and later Almohads.

Robert worked from an Arabic original now usually identified as *Masāʾil Khālid li-Maryānus al-rāhib* (The Questions of Khalid to the Monk Maryanus) or a text from the Jabirian corpus. The Latin title he gave it—*Liber de compositione alchemiae*—sounds dry, but the content is anything but. It is framed as a dramatic dialogue between a Christian hermit named Morienus (or Maryanus) and the Umayyad prince Khalid ibn Yazid.

### The Legend Within the Book: Morienus and Khalid

The story is pure medieval storytelling gold. Khalid ibn Yazid was a real historical figure, a prince of the Umayyad Caliphate in the late 7th century. After the dynasty’s bloody succession struggles, he supposedly retired from politics and devoted himself to learning. Legend says he became the first Muslim to seriously pursue alchemy. He searched far and wide until he found Morienus, a Christian hermit living in the mountains outside Alexandria or perhaps Damascus, who had inherited the true art from the ancient sages.

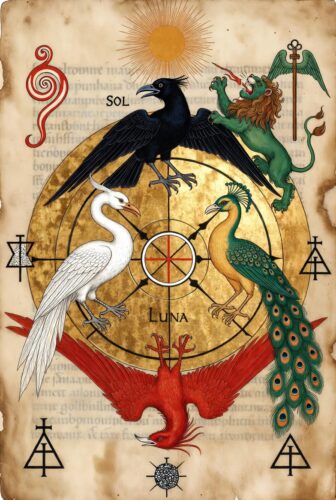

Khalid, being a prince, arrives with pomp and offers riches. Morienus, being a proper ascetic master, tests him mercilessly. He demands that Khalid abandon his worldly power, live simply, and prove his sincerity. Only then does the hermit reveal the secrets. The text includes practical instructions—how to prepare the “philosophical mercury,” the stages of the Great Work (nigredo, albedo, rubedo—the blackening, whitening, and reddening), the use of the “green lion” (a symbolic and sometimes literal substance, often linked to vitriol or antimony compounds that devour base metals), and the ultimate goal: the philosopher’s stone that transmutes and heals. The language is cryptic, as alchemical writing always is. Metals are called by planetary names (Sol for gold, Luna for silver, Saturn for lead). Processes are veiled in metaphors of marriage, death, and rebirth. Yet beneath the veil are real laboratory operations: distillation, sublimation, calcination, coagulation. Robert’s translation preserved these, making them accessible—dangerously accessible—to European readers for the first time.

Robert finished his work on February 11 and added a preface expressing both humility and excitement. He knew he was handling dangerous, almost sacred knowledge. In the medieval mind, manipulating the elements was close to playing God. Yet the intellectual hunger was too strong to resist.

### The Fire Spreads: From Segovia to the Monasteries and Courts

Manuscripts of Robert’s translation began to circulate almost immediately. Copies reached France, England, and Italy within decades. By the 13th century, alchemy was a recognized (if controversial) pursuit. Scholars like Albertus Magnus and his pupil Thomas Aquinas discussed it seriously, distinguishing between “true” alchemy and fraudulent puffery. Roger Bacon, the Franciscan friar often called the first experimental scientist, praised the experimental method he saw implied in alchemical texts and urged the study of “the secrets of nature.”

The practical results were astonishing. Alchemists, tinkering in their smoky laboratories, discovered or perfected:

- Mineral acids (sulfuric, nitric, hydrochloric) that could dissolve metals and etch glass.

- Improved distillation techniques that produced stronger alcohols and essential oils for medicine and perfume.

- New compounds used in metallurgy, dyeing, and glassmaking.

- Pharmacological preparations that, while often toxic, laid groundwork for later pharmacology.

Of course, there was plenty of comedy and tragedy mixed in. Kings and nobles, desperate for gold to fund wars or luxury, hired alchemists by the dozen. Some were genuine scholars; many were con artists. The “puffers”—so called because they spent hours blowing on furnaces—became stock figures of ridicule. One 14th-century story tells of an alchemist who convinced a duke he could multiply gold. He secretly added real gold filings to the crucible while the duke wasn’t looking, then “produced” more than he started with. When the trick was discovered, the alchemist wisely fled before the duke’s gratitude turned to rage.

Yet even the failures advanced knowledge. Every exploded retort, every batch of foul-smelling sludge taught something about chemical behavior. The quest for the elixir of life led to better understanding of distillation and preservation. The search for the stone pushed the boundaries of apparatus design—bellows, furnaces, balances—that would later serve genuine chemistry.

By the Renaissance, alchemy had become a full-blown intellectual movement. Figures like Paracelsus rejected the old sulfur-mercury theory in favor of a new tria prima (sulfur, mercury, salt) and revolutionized medicine with chemical remedies. John Dee, astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, combined alchemy with angel magic and mathematics. Even Isaac Newton, the towering genius of the Scientific Revolution, spent more time on alchemy than on calculus or optics—thousands of pages of notes, conducted in secret.

The irony is delicious: the mystical, often fraudulent pursuit of turning lead into gold helped create the rational, empirical science that eventually declared alchemy impossible (at least by chemical means—nuclear transmutation is another story). Robert Boyle’s *The Sceptical Chymist* (1661) is usually seen as the death knell of traditional alchemy, yet Boyle himself was deeply immersed in alchemical experiments. The laboratory techniques, the emphasis on observation and repetition, the very idea that nature could be manipulated through human ingenuity—all flowed from that first Latin translation completed on February 11, 1144.

The language is cryptic, as alchemical writing always is. Metals are called by planetary names (Sol for gold, Luna for silver, Saturn for lead). Processes are veiled in metaphors of marriage, death, and rebirth. Yet beneath the veil are real laboratory operations: distillation, sublimation, calcination, coagulation. Robert’s translation preserved these, making them accessible—dangerously accessible—to European readers for the first time.

Robert finished his work on February 11 and added a preface expressing both humility and excitement. He knew he was handling dangerous, almost sacred knowledge. In the medieval mind, manipulating the elements was close to playing God. Yet the intellectual hunger was too strong to resist.

### The Fire Spreads: From Segovia to the Monasteries and Courts

Manuscripts of Robert’s translation began to circulate almost immediately. Copies reached France, England, and Italy within decades. By the 13th century, alchemy was a recognized (if controversial) pursuit. Scholars like Albertus Magnus and his pupil Thomas Aquinas discussed it seriously, distinguishing between “true” alchemy and fraudulent puffery. Roger Bacon, the Franciscan friar often called the first experimental scientist, praised the experimental method he saw implied in alchemical texts and urged the study of “the secrets of nature.”

The practical results were astonishing. Alchemists, tinkering in their smoky laboratories, discovered or perfected:

- Mineral acids (sulfuric, nitric, hydrochloric) that could dissolve metals and etch glass.

- Improved distillation techniques that produced stronger alcohols and essential oils for medicine and perfume.

- New compounds used in metallurgy, dyeing, and glassmaking.

- Pharmacological preparations that, while often toxic, laid groundwork for later pharmacology.

Of course, there was plenty of comedy and tragedy mixed in. Kings and nobles, desperate for gold to fund wars or luxury, hired alchemists by the dozen. Some were genuine scholars; many were con artists. The “puffers”—so called because they spent hours blowing on furnaces—became stock figures of ridicule. One 14th-century story tells of an alchemist who convinced a duke he could multiply gold. He secretly added real gold filings to the crucible while the duke wasn’t looking, then “produced” more than he started with. When the trick was discovered, the alchemist wisely fled before the duke’s gratitude turned to rage.

Yet even the failures advanced knowledge. Every exploded retort, every batch of foul-smelling sludge taught something about chemical behavior. The quest for the elixir of life led to better understanding of distillation and preservation. The search for the stone pushed the boundaries of apparatus design—bellows, furnaces, balances—that would later serve genuine chemistry.

By the Renaissance, alchemy had become a full-blown intellectual movement. Figures like Paracelsus rejected the old sulfur-mercury theory in favor of a new tria prima (sulfur, mercury, salt) and revolutionized medicine with chemical remedies. John Dee, astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, combined alchemy with angel magic and mathematics. Even Isaac Newton, the towering genius of the Scientific Revolution, spent more time on alchemy than on calculus or optics—thousands of pages of notes, conducted in secret.

The irony is delicious: the mystical, often fraudulent pursuit of turning lead into gold helped create the rational, empirical science that eventually declared alchemy impossible (at least by chemical means—nuclear transmutation is another story). Robert Boyle’s *The Sceptical Chymist* (1661) is usually seen as the death knell of traditional alchemy, yet Boyle himself was deeply immersed in alchemical experiments. The laboratory techniques, the emphasis on observation and repetition, the very idea that nature could be manipulated through human ingenuity—all flowed from that first Latin translation completed on February 11, 1144. ### The Human Drama Behind the Science

It is easy to focus on the intellectual lineage, but the human stories are what make this history sing. Imagine Robert in Segovia: an Englishman far from the green fields of home, surrounded by the sounds of a frontier city—mules on cobblestones, the call to prayer from a distant mosque still in use, the hammering of armorers preparing for the next campaign against the Moors. He is learning Arabic, a language of poets and philosophers, from tutors who might have viewed him with suspicion or pragmatic tolerance. Every technical term is a battle: how do you render *al-iksir* (elixir) or the mysterious *al-kibrit* (sulfur) so that a European reader understands?

The broader context is one of violent collision and quiet collaboration. The Second Crusade was being preached around this time (it would launch in 1147). Yet in the translation workshops, Christians, Jews, and Muslims worked side by side. Knowledge did not respect the boundaries of holy war. Robert’s work is a testament to the power of curiosity to transcend tribalism.

The *Liber de compositione alchemiae* itself carries a moral lesson that feels surprisingly modern. Morienus tells Khalid that true alchemy requires purity of heart. The alchemist must master himself before he can master matter. Greed dooms the quest; humility and perseverance may reward it. Whether or not the stone exists, the discipline of the laboratory forges character.

### From Distant History to Your Daily Laboratory

Ninety percent of this tale belongs to the past, as it should. But the remaining ten percent is the living spark you can carry forward. The outcome of Robert’s quiet labor on that February day was nothing less than the seeding of the experimental mindset in the West. One man’s decision to cross cultures, master a difficult language, and translate obscure knowledge created ripples that became waves of discovery. You do not need to invent modern chemistry to reap similar rewards. You only need to become the alchemist of your own life.

Here is how a person benefits today by applying the lessons of that distant February 11:

- **Cross-cultural knowledge acquisition builds unexpected superpowers.** Robert left the familiar to learn Arabic and unlock entire libraries. Today, deliberately studying ideas, techniques, or mindsets from outside your native culture (whether Japanese business philosophy, Indian contemplative practices, or African storytelling traditions) expands your mental models and gives you tools others lack. The benefit is resilience and creativity in an increasingly connected world.

- **Persistent, humble experimentation turns repeated failure into compound interest.** Alchemists endured explosions, toxic fumes, and years of null results. Their notebooks—when they kept them—were records of disciplined trial and error. In modern life, this translates to treating your career, health, relationships, and skills as a laboratory. Each setback is data. The person who logs their attempts, adjusts variables, and keeps the furnace burning eventually achieves transformations that look like magic to outsiders.

- **The inner work precedes the outer result.** Morienus insisted Khalid purify his intentions. Modern psychology and performance research confirm that self-mastery—managing impulses, cultivating focus, aligning actions with values—is the true “philosopher’s stone.” External achievements built on shaky character collapse; those built on inner refinement endure.

- **Obscure, patient labor can have outsized historical impact.** Robert was not a king or general. He was a translator with a deadline. Most days felt ordinary. Yet his single completed manuscript helped birth a tradition that influenced Newton and Lavoisier. This reminds us that seemingly small, consistent contributions—writing daily, mentoring quietly, refining a craft—accumulate into legacies we cannot foresee.

**Your Personal 90-Day Alchemical Transformation Plan**

To make this concrete, here is a specific, actionable plan inspired directly by Robert’s example and the alchemical tradition. Treat your life as the prima materia (raw material) and follow the classic stages with modern discipline.

**Weeks 1–2: The Nigredo (Blackening – Breaking Down the Old)**

Identify three “base metals” in your life—habits, situations, or mindsets that hold you back (e.g., mindless scrolling, procrastination on a key project, negative self-talk). Keep a daily laboratory notebook: every evening, record what you observed, what triggered the behavior, and one small experiment you will try tomorrow. The goal is not perfection but honest observation. Burn away illusion through radical honesty.

**Weeks 3–6: The Albedo (Whitening – Purification and Clarification)**

Introduce structure. Choose one high-leverage skill or domain (public speaking, a language, financial literacy, physical fitness) and study it like Robert studied Arabic. Dedicate 45 focused minutes daily using the Pomodoro technique. Source materials from outside your usual bubble—books, teachers, or communities from different cultures or eras. Track progress quantitatively (words learned, pounds lifted, dollars saved) and qualitatively (how you feel). This is the stage of washing the material, removing impurities.

**Weeks 7–10: The Citrinitas (Yellowing – Energizing and Integration)**

Apply what you have learned in real-world “furnace” conditions. Run deliberate experiments: pitch the new idea at work, have the difficult conversation, launch the small side project. Expect failures—the alchemists did. After each, perform a “post-mortem distillation”: What worked? What vaporized? What residue remains useful? Adjust and repeat. This stage builds heat and momentum.

**Weeks 11–12: The Rubedo (Reddening – The Final Coagulation)**

Synthesize. Create a tangible “stone”—a completed project, a new habit stack, a documented system that others can use. Share it modestly. Reflect on the inner changes: greater patience, sharper focus, deeper curiosity. Celebrate not with fanfare but with a ritual acknowledgment that the work itself was the reward.

**Maintenance: The Eternal Laboratory**

There is no final “done.” Like the alchemists who kept their fires burning for decades, schedule weekly reviews and daily micro-experiments. Read one page of something challenging. Try one new variable in your routines. Stay humble—true mastery always reveals how much more there is to learn.

The beauty of this approach is its universality. Whether you are a student, entrepreneur, parent, or retiree, the laboratory is portable. Your kitchen becomes a site for nutritional experiments, your commute a classroom for language tapes or podcasts, your journal the vellum on which you record the Great Work.

### The Human Drama Behind the Science

It is easy to focus on the intellectual lineage, but the human stories are what make this history sing. Imagine Robert in Segovia: an Englishman far from the green fields of home, surrounded by the sounds of a frontier city—mules on cobblestones, the call to prayer from a distant mosque still in use, the hammering of armorers preparing for the next campaign against the Moors. He is learning Arabic, a language of poets and philosophers, from tutors who might have viewed him with suspicion or pragmatic tolerance. Every technical term is a battle: how do you render *al-iksir* (elixir) or the mysterious *al-kibrit* (sulfur) so that a European reader understands?

The broader context is one of violent collision and quiet collaboration. The Second Crusade was being preached around this time (it would launch in 1147). Yet in the translation workshops, Christians, Jews, and Muslims worked side by side. Knowledge did not respect the boundaries of holy war. Robert’s work is a testament to the power of curiosity to transcend tribalism.

The *Liber de compositione alchemiae* itself carries a moral lesson that feels surprisingly modern. Morienus tells Khalid that true alchemy requires purity of heart. The alchemist must master himself before he can master matter. Greed dooms the quest; humility and perseverance may reward it. Whether or not the stone exists, the discipline of the laboratory forges character.

### From Distant History to Your Daily Laboratory

Ninety percent of this tale belongs to the past, as it should. But the remaining ten percent is the living spark you can carry forward. The outcome of Robert’s quiet labor on that February day was nothing less than the seeding of the experimental mindset in the West. One man’s decision to cross cultures, master a difficult language, and translate obscure knowledge created ripples that became waves of discovery. You do not need to invent modern chemistry to reap similar rewards. You only need to become the alchemist of your own life.

Here is how a person benefits today by applying the lessons of that distant February 11:

- **Cross-cultural knowledge acquisition builds unexpected superpowers.** Robert left the familiar to learn Arabic and unlock entire libraries. Today, deliberately studying ideas, techniques, or mindsets from outside your native culture (whether Japanese business philosophy, Indian contemplative practices, or African storytelling traditions) expands your mental models and gives you tools others lack. The benefit is resilience and creativity in an increasingly connected world.

- **Persistent, humble experimentation turns repeated failure into compound interest.** Alchemists endured explosions, toxic fumes, and years of null results. Their notebooks—when they kept them—were records of disciplined trial and error. In modern life, this translates to treating your career, health, relationships, and skills as a laboratory. Each setback is data. The person who logs their attempts, adjusts variables, and keeps the furnace burning eventually achieves transformations that look like magic to outsiders.

- **The inner work precedes the outer result.** Morienus insisted Khalid purify his intentions. Modern psychology and performance research confirm that self-mastery—managing impulses, cultivating focus, aligning actions with values—is the true “philosopher’s stone.” External achievements built on shaky character collapse; those built on inner refinement endure.

- **Obscure, patient labor can have outsized historical impact.** Robert was not a king or general. He was a translator with a deadline. Most days felt ordinary. Yet his single completed manuscript helped birth a tradition that influenced Newton and Lavoisier. This reminds us that seemingly small, consistent contributions—writing daily, mentoring quietly, refining a craft—accumulate into legacies we cannot foresee.

**Your Personal 90-Day Alchemical Transformation Plan**

To make this concrete, here is a specific, actionable plan inspired directly by Robert’s example and the alchemical tradition. Treat your life as the prima materia (raw material) and follow the classic stages with modern discipline.

**Weeks 1–2: The Nigredo (Blackening – Breaking Down the Old)**

Identify three “base metals” in your life—habits, situations, or mindsets that hold you back (e.g., mindless scrolling, procrastination on a key project, negative self-talk). Keep a daily laboratory notebook: every evening, record what you observed, what triggered the behavior, and one small experiment you will try tomorrow. The goal is not perfection but honest observation. Burn away illusion through radical honesty.

**Weeks 3–6: The Albedo (Whitening – Purification and Clarification)**

Introduce structure. Choose one high-leverage skill or domain (public speaking, a language, financial literacy, physical fitness) and study it like Robert studied Arabic. Dedicate 45 focused minutes daily using the Pomodoro technique. Source materials from outside your usual bubble—books, teachers, or communities from different cultures or eras. Track progress quantitatively (words learned, pounds lifted, dollars saved) and qualitatively (how you feel). This is the stage of washing the material, removing impurities.

**Weeks 7–10: The Citrinitas (Yellowing – Energizing and Integration)**

Apply what you have learned in real-world “furnace” conditions. Run deliberate experiments: pitch the new idea at work, have the difficult conversation, launch the small side project. Expect failures—the alchemists did. After each, perform a “post-mortem distillation”: What worked? What vaporized? What residue remains useful? Adjust and repeat. This stage builds heat and momentum.

**Weeks 11–12: The Rubedo (Reddening – The Final Coagulation)**

Synthesize. Create a tangible “stone”—a completed project, a new habit stack, a documented system that others can use. Share it modestly. Reflect on the inner changes: greater patience, sharper focus, deeper curiosity. Celebrate not with fanfare but with a ritual acknowledgment that the work itself was the reward.

**Maintenance: The Eternal Laboratory**

There is no final “done.” Like the alchemists who kept their fires burning for decades, schedule weekly reviews and daily micro-experiments. Read one page of something challenging. Try one new variable in your routines. Stay humble—true mastery always reveals how much more there is to learn.

The beauty of this approach is its universality. Whether you are a student, entrepreneur, parent, or retiree, the laboratory is portable. Your kitchen becomes a site for nutritional experiments, your commute a classroom for language tapes or podcasts, your journal the vellum on which you record the Great Work. Robert of Chester probably never imagined that his careful Latin rendering of an Arabic dialogue would help lay the foundations for the modern world’s material prosperity and scientific worldview. He simply did the work in front of him with diligence and intellectual courage. That is the ultimate lesson of February 11, 1144: significance often hides in the quiet, persistent acts of translation—turning the foreign into the familiar, the obscure into the usable, the base into the noble.

So pick up your quill. The furnace is ready. The prima materia is whatever raw material your life offers today. The date is always February 11 in the laboratory of the self. Begin the composition. The transmutation awaits.

Robert of Chester probably never imagined that his careful Latin rendering of an Arabic dialogue would help lay the foundations for the modern world’s material prosperity and scientific worldview. He simply did the work in front of him with diligence and intellectual courage. That is the ultimate lesson of February 11, 1144: significance often hides in the quiet, persistent acts of translation—turning the foreign into the familiar, the obscure into the usable, the base into the noble.

So pick up your quill. The furnace is ready. The prima materia is whatever raw material your life offers today. The date is always February 11 in the laboratory of the self. Begin the composition. The transmutation awaits.

This is not the story of a flashy battle or a famous coronation. It is the story of a translator in a borderland city, hunched over his desk while the Reconquista rumbled in the distance. It is a tale of cultural theft in the best possible sense—stealing knowledge across enemy lines—and it changed the trajectory of Western science more profoundly than most cannonades or coronations ever did. And by the end of this long ramble through the dusty corridors of the 12th century, you will see exactly how the spirit of that February day can become your own personal laboratory for turning the base metal of ordinary life into something far more valuable. ### The World That Needed a Spark To understand why Robert’s translation mattered so much, you must first understand how intellectually starved Latin Europe was in the early 12th century. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed nearly 700 years earlier. What remained was a patchwork of feudal kingdoms, monasteries preserving fragments of classical learning, and a Church that was often more concerned with orthodoxy than experimentation. Greek texts survived mostly in Arabic translations made by scholars in Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba during the Islamic Golden Age. The great libraries of the Caliphate had safeguarded Aristotle, Plato, Galen, and the Hermetic writings, then improved upon them with original research in mathematics, optics, medicine, and—yes—alchemy. Alchemy in the Islamic world was never the cartoonish gold-making scam it later became in the popular imagination. It was a sophisticated philosophical and practical discipline. Thinkers like Jabir ibn Hayyan (known to the Latins as Geber, fl. late 8th–early 9th century) developed an experimental method centuries before the so-called Scientific Revolution. Jabir emphasized repeatable processes, laboratory apparatus (alembics, stills, furnaces), and a theory that all metals were composed of two principles: sulfur (the fiery, combustible spirit) and mercury (the fluid, metallic body). By purifying and recombining these principles in the correct ratios, one could theoretically transmute base metals into noble ones or create the elixir of life.

Jabir’s enormous corpus—much of it probably written by later followers in his school—stressed balance, the four elements of Aristotle (earth, air, fire, water) modified by the Islamic emphasis on qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry), and a spiritual dimension: the alchemist must purify his own soul to succeed in purifying matter. This was serious philosophy dressed in the language of the laboratory. By the 12th century, Christian Europe was waking up to this treasure trove. The Reconquista had turned Spain into a porous frontier. Cities like Toledo, Barcelona, and Segovia became magnets for ambitious scholars willing to learn Arabic from Muslim and Jewish tutors. These men—often clerics with a taste for the forbidden or the useful—formed what historians now call the “Toledo School of Translators,” though the work happened in many places. They translated everything: Ptolemy’s astronomy, Avicenna’s medicine, Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra (which gave us the word “algorithm”), and, thanks to Robert, the secrets of alchemy. ### Enter Robert of Chester, the Unlikely Pioneer We know frustratingly little about Robert the man. He was English, probably from the northwest (hence “of Chester”). By the 1140s he was in Spain, part of a loose network of translators that included the remarkable Hermann of Carinthia (also called Hermann the Dalmatian), a colorful character who roamed from the Pyrenees to the Ebro River in search of knowledge. Robert and Hermann seem to have collaborated or at least inspired each other. Robert also translated Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra in 1145—the first Latin version of that groundbreaking text—and astronomical works. He may later have become archdeacon of Pamplona. But his most explosive contribution came on that cold February day in Segovia. Why Segovia? The city sat in the Kingdom of Castile, strategically located on the route between the Christian north and the Muslim south. Its Roman aqueduct still functioned, a daily reminder of lost grandeur that perhaps inspired men like Robert to recover ancient wisdom. The atmosphere was one of pragmatic curiosity rather than pure scholarship. Christian rulers needed administrative knowledge, medical expertise, and—let’s be honest—any technological edge they could get in their long war against the Almoravids and later Almohads. Robert worked from an Arabic original now usually identified as *Masāʾil Khālid li-Maryānus al-rāhib* (The Questions of Khalid to the Monk Maryanus) or a text from the Jabirian corpus. The Latin title he gave it—*Liber de compositione alchemiae*—sounds dry, but the content is anything but. It is framed as a dramatic dialogue between a Christian hermit named Morienus (or Maryanus) and the Umayyad prince Khalid ibn Yazid. ### The Legend Within the Book: Morienus and Khalid The story is pure medieval storytelling gold. Khalid ibn Yazid was a real historical figure, a prince of the Umayyad Caliphate in the late 7th century. After the dynasty’s bloody succession struggles, he supposedly retired from politics and devoted himself to learning. Legend says he became the first Muslim to seriously pursue alchemy. He searched far and wide until he found Morienus, a Christian hermit living in the mountains outside Alexandria or perhaps Damascus, who had inherited the true art from the ancient sages. Khalid, being a prince, arrives with pomp and offers riches. Morienus, being a proper ascetic master, tests him mercilessly. He demands that Khalid abandon his worldly power, live simply, and prove his sincerity. Only then does the hermit reveal the secrets. The text includes practical instructions—how to prepare the “philosophical mercury,” the stages of the Great Work (nigredo, albedo, rubedo—the blackening, whitening, and reddening), the use of the “green lion” (a symbolic and sometimes literal substance, often linked to vitriol or antimony compounds that devour base metals), and the ultimate goal: the philosopher’s stone that transmutes and heals.

The language is cryptic, as alchemical writing always is. Metals are called by planetary names (Sol for gold, Luna for silver, Saturn for lead). Processes are veiled in metaphors of marriage, death, and rebirth. Yet beneath the veil are real laboratory operations: distillation, sublimation, calcination, coagulation. Robert’s translation preserved these, making them accessible—dangerously accessible—to European readers for the first time. Robert finished his work on February 11 and added a preface expressing both humility and excitement. He knew he was handling dangerous, almost sacred knowledge. In the medieval mind, manipulating the elements was close to playing God. Yet the intellectual hunger was too strong to resist. ### The Fire Spreads: From Segovia to the Monasteries and Courts Manuscripts of Robert’s translation began to circulate almost immediately. Copies reached France, England, and Italy within decades. By the 13th century, alchemy was a recognized (if controversial) pursuit. Scholars like Albertus Magnus and his pupil Thomas Aquinas discussed it seriously, distinguishing between “true” alchemy and fraudulent puffery. Roger Bacon, the Franciscan friar often called the first experimental scientist, praised the experimental method he saw implied in alchemical texts and urged the study of “the secrets of nature.” The practical results were astonishing. Alchemists, tinkering in their smoky laboratories, discovered or perfected: - Mineral acids (sulfuric, nitric, hydrochloric) that could dissolve metals and etch glass. - Improved distillation techniques that produced stronger alcohols and essential oils for medicine and perfume. - New compounds used in metallurgy, dyeing, and glassmaking. - Pharmacological preparations that, while often toxic, laid groundwork for later pharmacology. Of course, there was plenty of comedy and tragedy mixed in. Kings and nobles, desperate for gold to fund wars or luxury, hired alchemists by the dozen. Some were genuine scholars; many were con artists. The “puffers”—so called because they spent hours blowing on furnaces—became stock figures of ridicule. One 14th-century story tells of an alchemist who convinced a duke he could multiply gold. He secretly added real gold filings to the crucible while the duke wasn’t looking, then “produced” more than he started with. When the trick was discovered, the alchemist wisely fled before the duke’s gratitude turned to rage. Yet even the failures advanced knowledge. Every exploded retort, every batch of foul-smelling sludge taught something about chemical behavior. The quest for the elixir of life led to better understanding of distillation and preservation. The search for the stone pushed the boundaries of apparatus design—bellows, furnaces, balances—that would later serve genuine chemistry. By the Renaissance, alchemy had become a full-blown intellectual movement. Figures like Paracelsus rejected the old sulfur-mercury theory in favor of a new tria prima (sulfur, mercury, salt) and revolutionized medicine with chemical remedies. John Dee, astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, combined alchemy with angel magic and mathematics. Even Isaac Newton, the towering genius of the Scientific Revolution, spent more time on alchemy than on calculus or optics—thousands of pages of notes, conducted in secret. The irony is delicious: the mystical, often fraudulent pursuit of turning lead into gold helped create the rational, empirical science that eventually declared alchemy impossible (at least by chemical means—nuclear transmutation is another story). Robert Boyle’s *The Sceptical Chymist* (1661) is usually seen as the death knell of traditional alchemy, yet Boyle himself was deeply immersed in alchemical experiments. The laboratory techniques, the emphasis on observation and repetition, the very idea that nature could be manipulated through human ingenuity—all flowed from that first Latin translation completed on February 11, 1144.

### The Human Drama Behind the Science It is easy to focus on the intellectual lineage, but the human stories are what make this history sing. Imagine Robert in Segovia: an Englishman far from the green fields of home, surrounded by the sounds of a frontier city—mules on cobblestones, the call to prayer from a distant mosque still in use, the hammering of armorers preparing for the next campaign against the Moors. He is learning Arabic, a language of poets and philosophers, from tutors who might have viewed him with suspicion or pragmatic tolerance. Every technical term is a battle: how do you render *al-iksir* (elixir) or the mysterious *al-kibrit* (sulfur) so that a European reader understands? The broader context is one of violent collision and quiet collaboration. The Second Crusade was being preached around this time (it would launch in 1147). Yet in the translation workshops, Christians, Jews, and Muslims worked side by side. Knowledge did not respect the boundaries of holy war. Robert’s work is a testament to the power of curiosity to transcend tribalism. The *Liber de compositione alchemiae* itself carries a moral lesson that feels surprisingly modern. Morienus tells Khalid that true alchemy requires purity of heart. The alchemist must master himself before he can master matter. Greed dooms the quest; humility and perseverance may reward it. Whether or not the stone exists, the discipline of the laboratory forges character. ### From Distant History to Your Daily Laboratory Ninety percent of this tale belongs to the past, as it should. But the remaining ten percent is the living spark you can carry forward. The outcome of Robert’s quiet labor on that February day was nothing less than the seeding of the experimental mindset in the West. One man’s decision to cross cultures, master a difficult language, and translate obscure knowledge created ripples that became waves of discovery. You do not need to invent modern chemistry to reap similar rewards. You only need to become the alchemist of your own life. Here is how a person benefits today by applying the lessons of that distant February 11: - **Cross-cultural knowledge acquisition builds unexpected superpowers.** Robert left the familiar to learn Arabic and unlock entire libraries. Today, deliberately studying ideas, techniques, or mindsets from outside your native culture (whether Japanese business philosophy, Indian contemplative practices, or African storytelling traditions) expands your mental models and gives you tools others lack. The benefit is resilience and creativity in an increasingly connected world. - **Persistent, humble experimentation turns repeated failure into compound interest.** Alchemists endured explosions, toxic fumes, and years of null results. Their notebooks—when they kept them—were records of disciplined trial and error. In modern life, this translates to treating your career, health, relationships, and skills as a laboratory. Each setback is data. The person who logs their attempts, adjusts variables, and keeps the furnace burning eventually achieves transformations that look like magic to outsiders. - **The inner work precedes the outer result.** Morienus insisted Khalid purify his intentions. Modern psychology and performance research confirm that self-mastery—managing impulses, cultivating focus, aligning actions with values—is the true “philosopher’s stone.” External achievements built on shaky character collapse; those built on inner refinement endure. - **Obscure, patient labor can have outsized historical impact.** Robert was not a king or general. He was a translator with a deadline. Most days felt ordinary. Yet his single completed manuscript helped birth a tradition that influenced Newton and Lavoisier. This reminds us that seemingly small, consistent contributions—writing daily, mentoring quietly, refining a craft—accumulate into legacies we cannot foresee. **Your Personal 90-Day Alchemical Transformation Plan** To make this concrete, here is a specific, actionable plan inspired directly by Robert’s example and the alchemical tradition. Treat your life as the prima materia (raw material) and follow the classic stages with modern discipline. **Weeks 1–2: The Nigredo (Blackening – Breaking Down the Old)** Identify three “base metals” in your life—habits, situations, or mindsets that hold you back (e.g., mindless scrolling, procrastination on a key project, negative self-talk). Keep a daily laboratory notebook: every evening, record what you observed, what triggered the behavior, and one small experiment you will try tomorrow. The goal is not perfection but honest observation. Burn away illusion through radical honesty. **Weeks 3–6: The Albedo (Whitening – Purification and Clarification)** Introduce structure. Choose one high-leverage skill or domain (public speaking, a language, financial literacy, physical fitness) and study it like Robert studied Arabic. Dedicate 45 focused minutes daily using the Pomodoro technique. Source materials from outside your usual bubble—books, teachers, or communities from different cultures or eras. Track progress quantitatively (words learned, pounds lifted, dollars saved) and qualitatively (how you feel). This is the stage of washing the material, removing impurities. **Weeks 7–10: The Citrinitas (Yellowing – Energizing and Integration)** Apply what you have learned in real-world “furnace” conditions. Run deliberate experiments: pitch the new idea at work, have the difficult conversation, launch the small side project. Expect failures—the alchemists did. After each, perform a “post-mortem distillation”: What worked? What vaporized? What residue remains useful? Adjust and repeat. This stage builds heat and momentum. **Weeks 11–12: The Rubedo (Reddening – The Final Coagulation)** Synthesize. Create a tangible “stone”—a completed project, a new habit stack, a documented system that others can use. Share it modestly. Reflect on the inner changes: greater patience, sharper focus, deeper curiosity. Celebrate not with fanfare but with a ritual acknowledgment that the work itself was the reward. **Maintenance: The Eternal Laboratory** There is no final “done.” Like the alchemists who kept their fires burning for decades, schedule weekly reviews and daily micro-experiments. Read one page of something challenging. Try one new variable in your routines. Stay humble—true mastery always reveals how much more there is to learn. The beauty of this approach is its universality. Whether you are a student, entrepreneur, parent, or retiree, the laboratory is portable. Your kitchen becomes a site for nutritional experiments, your commute a classroom for language tapes or podcasts, your journal the vellum on which you record the Great Work.

Robert of Chester probably never imagined that his careful Latin rendering of an Arabic dialogue would help lay the foundations for the modern world’s material prosperity and scientific worldview. He simply did the work in front of him with diligence and intellectual courage. That is the ultimate lesson of February 11, 1144: significance often hides in the quiet, persistent acts of translation—turning the foreign into the familiar, the obscure into the usable, the base into the noble. So pick up your quill. The furnace is ready. The prima materia is whatever raw material your life offers today. The date is always February 11 in the laboratory of the self. Begin the composition. The transmutation awaits.