Ah, February 5th – a date that might not ring many bells in the grand symphony of history, unless you're a fan of ancient Roman drama or have a peculiar fascination with seismic shenanigans. But rewind the clock to 62 AD, and this seemingly ordinary winter day in the bustling Roman resort town of Pompeii turned into a literal earth-shattering spectacle. We're talking about the Pompeii earthquake, a Magnitude 5-6 beast that didn't just rattle windows – it toppled temples, cracked aqueducts, and set the stage for one of history's most infamous volcanic tantrums 17 years later. This wasn't your run-of-the-mill tremor; it was a significant harbinger of doom, a wake-up call from the gods (or geology, depending on your worldview) that the ground beneath your feet isn't always as reliable as it seems.

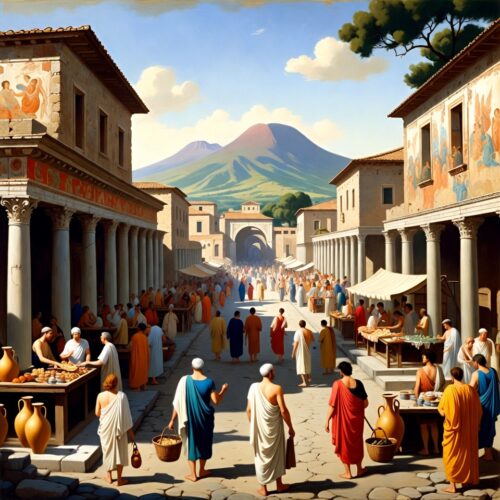

Picture this: Pompeii in the early 60s AD wasn't some dusty backwater. It was a thriving coastal gem in the Campania region of Italy, nestled at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, which at the time looked more like a sleepy green hill than a fire-breathing monster. With a population hovering around 20,000 souls – a mix of wealthy Roman elites escaping the urban grind of Rome, local farmers peddling their wares, slaves hustling in the shadows, and merchants hawking everything from garum (that's fermented fish sauce, folks – the ketchup of ancient Rome) to exotic imports from across the empire – Pompeii was a hotspot. Literally, as we'd find out later. The town boasted frescoed villas, bustling forums, amphitheaters where gladiators duked it out for cheers, and bathhouses where deals were sealed amid steam and gossip. It was the Vegas of its day, minus the neon lights, but with plenty of vice and vino. But beneath this vibrant facade lurked a geological time bomb. The Italian peninsula sits on a tectonic tango between the African and Eurasian plates, part of the Apennine mountain chain's ongoing stretch-fest that's been widening the Tyrrhenian Sea for eons. Vesuvius itself is a stratovolcano, born from this subduction zone where one plate dives under another, melting rock into magma that occasionally decides to party on the surface. Historians and geologists now know that the area around the Bay of Naples was no stranger to shakes – minor tremors were as common as bad chariot traffic. But on February 5, 62 AD, things got real. The quake struck with an estimated magnitude between 5.2 and 6.1 on the Richter scale, packing an intensity of IX to X on the Mercalli scale. For the uninitiated, that's "violent" to "extreme" – think buildings crumbling like overbaked biscotti, ground waves visible to the eye, and panic spreading faster than a rumor in the forum.

The epicenter? Right smack in the zone of active extensional faulting on Vesuvius's southern flank, involving a messy web of NW-SE and NE-SW oblique-slip normal faults, plus some east-west normals for good measure. The shaking elongated in a west-northwest to east-southeast direction, with a focal depth of about 5-6 kilometers – shallow enough to feel like the underworld was knocking. And knock it did. Eyewitness accounts paint a vivid picture of chaos. The philosopher Seneca the Younger, that stoic sage and advisor to Emperor Nero (more on him later), was quick to document the event in his work *Naturales Quaestiones* (Natural Questions), Book VI, titled *De Terrae Motu* (On Earthquakes). Seneca, ever the intellectual show-off, wasn't just reporting; he was philosophizing. He described how the quake hit during the consulship of Publius Marius and Lucius Afinius Gallus – pinning it firmly to 62 AD, though he initially flubbed the consuls' names in an early draft, leading to some scholarly squabbles over whether it was 62 or 63. (Spoiler: Tacitus, another Roman historian writing decades later, backs 62.)

Seneca's account is a goldmine of details, blending science (by ancient standards) with a dash of drama. He notes that the tremor struck in broad daylight, catching everyone off guard. "The earth shook," he writes, "and the sea was driven back, as if the gods had decided to rearrange the landscape." Buildings swayed like drunken sailors, roofs caved in, and statues toppled from their pedestals. In Pompeii, the Temple of Jupiter – that grand centerpiece of the forum, dedicated to the king of the gods himself – partially collapsed, its columns cracking and pediments tumbling. Imagine the irony: Jupiter's house getting wrecked by what many Romans would attribute to his thunderbolts or divine displeasure. The Vesuvius Gate, a key entry point to the city, buckled under the strain, its arches fracturing. The Aquarium of Caesar, possibly a public water feature or bath complex, suffered major damage, with pipes bursting and water flooding streets already choked with debris.

But beneath this vibrant facade lurked a geological time bomb. The Italian peninsula sits on a tectonic tango between the African and Eurasian plates, part of the Apennine mountain chain's ongoing stretch-fest that's been widening the Tyrrhenian Sea for eons. Vesuvius itself is a stratovolcano, born from this subduction zone where one plate dives under another, melting rock into magma that occasionally decides to party on the surface. Historians and geologists now know that the area around the Bay of Naples was no stranger to shakes – minor tremors were as common as bad chariot traffic. But on February 5, 62 AD, things got real. The quake struck with an estimated magnitude between 5.2 and 6.1 on the Richter scale, packing an intensity of IX to X on the Mercalli scale. For the uninitiated, that's "violent" to "extreme" – think buildings crumbling like overbaked biscotti, ground waves visible to the eye, and panic spreading faster than a rumor in the forum.

The epicenter? Right smack in the zone of active extensional faulting on Vesuvius's southern flank, involving a messy web of NW-SE and NE-SW oblique-slip normal faults, plus some east-west normals for good measure. The shaking elongated in a west-northwest to east-southeast direction, with a focal depth of about 5-6 kilometers – shallow enough to feel like the underworld was knocking. And knock it did. Eyewitness accounts paint a vivid picture of chaos. The philosopher Seneca the Younger, that stoic sage and advisor to Emperor Nero (more on him later), was quick to document the event in his work *Naturales Quaestiones* (Natural Questions), Book VI, titled *De Terrae Motu* (On Earthquakes). Seneca, ever the intellectual show-off, wasn't just reporting; he was philosophizing. He described how the quake hit during the consulship of Publius Marius and Lucius Afinius Gallus – pinning it firmly to 62 AD, though he initially flubbed the consuls' names in an early draft, leading to some scholarly squabbles over whether it was 62 or 63. (Spoiler: Tacitus, another Roman historian writing decades later, backs 62.)

Seneca's account is a goldmine of details, blending science (by ancient standards) with a dash of drama. He notes that the tremor struck in broad daylight, catching everyone off guard. "The earth shook," he writes, "and the sea was driven back, as if the gods had decided to rearrange the landscape." Buildings swayed like drunken sailors, roofs caved in, and statues toppled from their pedestals. In Pompeii, the Temple of Jupiter – that grand centerpiece of the forum, dedicated to the king of the gods himself – partially collapsed, its columns cracking and pediments tumbling. Imagine the irony: Jupiter's house getting wrecked by what many Romans would attribute to his thunderbolts or divine displeasure. The Vesuvius Gate, a key entry point to the city, buckled under the strain, its arches fracturing. The Aquarium of Caesar, possibly a public water feature or bath complex, suffered major damage, with pipes bursting and water flooding streets already choked with debris. But it wasn't just Pompeii feeling the wrath. Neighboring Herculaneum, a posher seaside retreat for the ultra-rich, took a beating too. Seneca reports that "a large part of the town of Herculaneum fell," with shaky remnants left standing in nearby Nuceria. Even Naples, that bustling port city about 15 miles away, wasn't spared – though its damage was lighter, mostly to private homes and villas, with public buildings holding up better. Villas collapsed in the countryside, and widespread tremors rippled through the region without always causing total ruin. One bizarre detail from Seneca: 600 sheep perished, not from falling rubble, but from "poisonous air" that tainted the atmosphere. Was this an early whiff of volcanic gases seeping from Vesuvius? Modern geologists think so – sulfurous fumes or carbon dioxide releases could have asphyxiated livestock, hinting that the quake was tied to magmatic stirrings deep below. It's like nature's subtle spoiler alert for the 79 AD blockbuster.

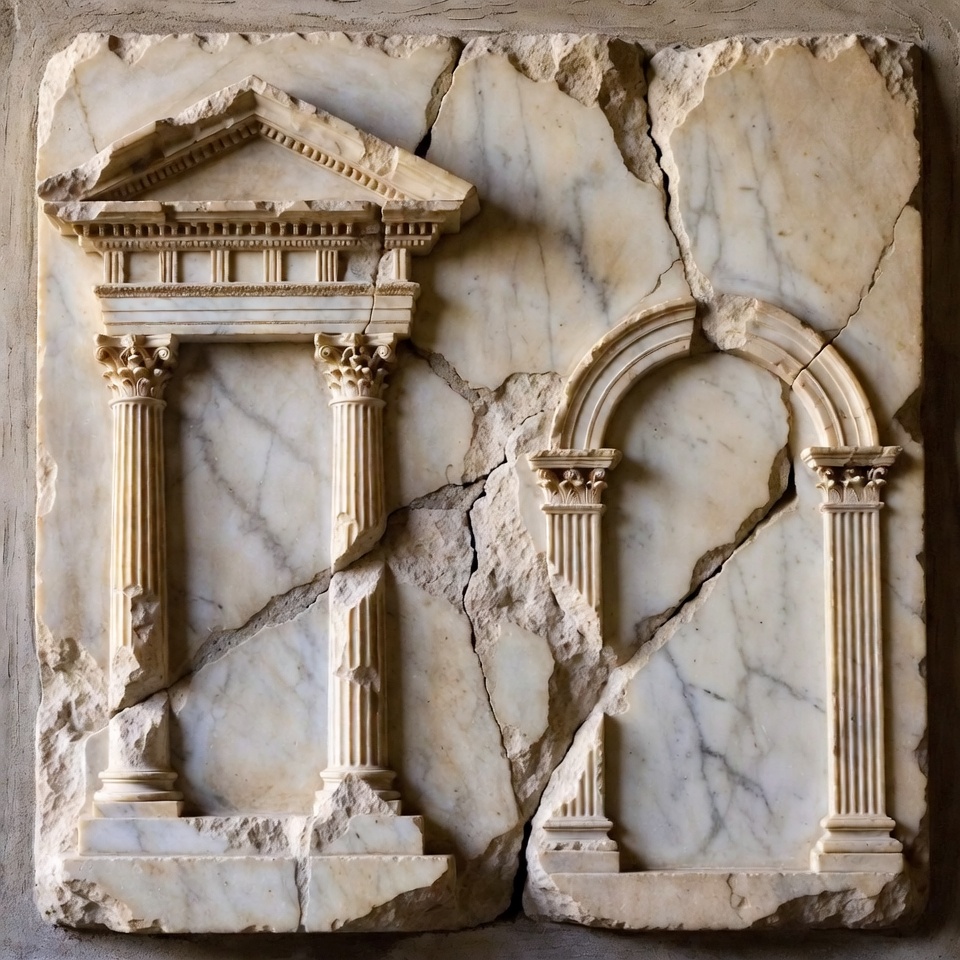

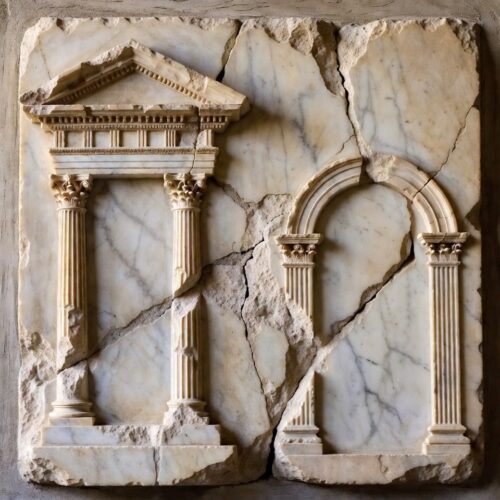

Human casualties? The ancient sources are frustratingly vague – no neat body counts like in modern disaster reports. But extrapolating from the scale, deaths likely numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands, across the region. Some folks, traumatized by the ordeal, "started to wander about, unable to regain control over themselves," as Seneca puts it. Picture shell-shocked survivors stumbling through rubble-strewn streets, their world literally upended. Tacitus, in his *Annals*, gives a curt nod: "An earthquake demolished a large part of Pompeii, a populous town in Campania." Brevity is the soul of wit, but here it's the soul of understatement. Archaeological evidence fills in the gaps where words fail. Excavations at Pompeii reveal telltale signs: cracked walls patched with hasty repairs, floors relaid over subsidence craters, and buildings mid-renovation when the volcano hit in 79. One standout artifact? The bas-reliefs from the House of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, a wealthy banker whose lararium (household shrine) featured carved stone panels depicting the quake's havoc. One shows the Temple of Jupiter teetering, another the Vesuvius Gate askew – like ancient disaster selfies, capturing the moment for posterity. Tragically, Iucundus himself may have perished in the quake; his house shows signs of abandonment post-62.

But it wasn't just Pompeii feeling the wrath. Neighboring Herculaneum, a posher seaside retreat for the ultra-rich, took a beating too. Seneca reports that "a large part of the town of Herculaneum fell," with shaky remnants left standing in nearby Nuceria. Even Naples, that bustling port city about 15 miles away, wasn't spared – though its damage was lighter, mostly to private homes and villas, with public buildings holding up better. Villas collapsed in the countryside, and widespread tremors rippled through the region without always causing total ruin. One bizarre detail from Seneca: 600 sheep perished, not from falling rubble, but from "poisonous air" that tainted the atmosphere. Was this an early whiff of volcanic gases seeping from Vesuvius? Modern geologists think so – sulfurous fumes or carbon dioxide releases could have asphyxiated livestock, hinting that the quake was tied to magmatic stirrings deep below. It's like nature's subtle spoiler alert for the 79 AD blockbuster.

Human casualties? The ancient sources are frustratingly vague – no neat body counts like in modern disaster reports. But extrapolating from the scale, deaths likely numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands, across the region. Some folks, traumatized by the ordeal, "started to wander about, unable to regain control over themselves," as Seneca puts it. Picture shell-shocked survivors stumbling through rubble-strewn streets, their world literally upended. Tacitus, in his *Annals*, gives a curt nod: "An earthquake demolished a large part of Pompeii, a populous town in Campania." Brevity is the soul of wit, but here it's the soul of understatement. Archaeological evidence fills in the gaps where words fail. Excavations at Pompeii reveal telltale signs: cracked walls patched with hasty repairs, floors relaid over subsidence craters, and buildings mid-renovation when the volcano hit in 79. One standout artifact? The bas-reliefs from the House of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, a wealthy banker whose lararium (household shrine) featured carved stone panels depicting the quake's havoc. One shows the Temple of Jupiter teetering, another the Vesuvius Gate askew – like ancient disaster selfies, capturing the moment for posterity. Tragically, Iucundus himself may have perished in the quake; his house shows signs of abandonment post-62. The aftermath was a masterclass in Roman resilience – or hubris, depending on your view. Reconstruction kicked off almost immediately, fueled by imperial aid and private fortunes. Emperor Nero, that flamboyant fiddle-player (though the fiddle story's a myth), sent relief funds and engineers. By some accounts, he even visited the area, though a later quake in 64 AD during one of his performances in Naples added a theatrical twist – the theater shook as he sang, which he took as applause from the gods. (Nero being Nero, he probably bowed.) In Pompeii, the forum was revamped, temples rebuilt with sturdier materials, and aqueducts reinforced. The Serino Aqueduct, which piped fresh water from the mountains, needed major fixes after fractures caused widespread shortages. Streets were repaved, homes retrofitted with anti-seismic designs like lighter roofs and flexible joints – early earthquake engineering, Roman style.

But here's the kicker: the rebuilding wasn't done by 79 AD. When Vesuvius erupted, Pompeii was still a construction zone. Scaffolding dotted temples, trenches scarred roads for pipe repairs, and some villas lay in ruins, their owners perhaps having fled after repeated aftershocks. Yes, the 62 quake wasn't a one-off. Scholars now believe it ushered in a swarm of seismic activity – smaller tremors plaguing the region for years. Pliny the Younger, in his letters describing the 79 eruption, mentions "earth tremors which were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania." Frequent? That's like saying Italian traffic is "lively." A quake in 64 AD rattled Nero's show in Naples, and ongoing shakes kept nerves frayed. Geologists link this to Vesuvius waking up after centuries of dormancy. The 62 quake may have fractured the crust, allowing magma to rise, pressurizing the system like a shaken soda bottle. By 79, pop went the volcano, burying Pompeii under 4-6 meters of ash and pumice, preserving it as a time capsule.

The aftermath was a masterclass in Roman resilience – or hubris, depending on your view. Reconstruction kicked off almost immediately, fueled by imperial aid and private fortunes. Emperor Nero, that flamboyant fiddle-player (though the fiddle story's a myth), sent relief funds and engineers. By some accounts, he even visited the area, though a later quake in 64 AD during one of his performances in Naples added a theatrical twist – the theater shook as he sang, which he took as applause from the gods. (Nero being Nero, he probably bowed.) In Pompeii, the forum was revamped, temples rebuilt with sturdier materials, and aqueducts reinforced. The Serino Aqueduct, which piped fresh water from the mountains, needed major fixes after fractures caused widespread shortages. Streets were repaved, homes retrofitted with anti-seismic designs like lighter roofs and flexible joints – early earthquake engineering, Roman style.

But here's the kicker: the rebuilding wasn't done by 79 AD. When Vesuvius erupted, Pompeii was still a construction zone. Scaffolding dotted temples, trenches scarred roads for pipe repairs, and some villas lay in ruins, their owners perhaps having fled after repeated aftershocks. Yes, the 62 quake wasn't a one-off. Scholars now believe it ushered in a swarm of seismic activity – smaller tremors plaguing the region for years. Pliny the Younger, in his letters describing the 79 eruption, mentions "earth tremors which were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania." Frequent? That's like saying Italian traffic is "lively." A quake in 64 AD rattled Nero's show in Naples, and ongoing shakes kept nerves frayed. Geologists link this to Vesuvius waking up after centuries of dormancy. The 62 quake may have fractured the crust, allowing magma to rise, pressurizing the system like a shaken soda bottle. By 79, pop went the volcano, burying Pompeii under 4-6 meters of ash and pumice, preserving it as a time capsule. Diving deeper into the social ripple effects, the quake reshaped Pompeii's society. Wealthy elites poured money into repairs, sparking a building boom that attracted laborers and artisans. Upper-story apartments proliferated to house the influx, turning some streets into proto-apartment blocks. An inscription hints at imperial intervention: a Vespasian-era agent stepping in for economic stabilization. But not everyone bounced back. Slaves and the poor likely bore the brunt, with shoddy tenements collapsing first. And culturally? The quake fueled superstition. Romans saw it as an omen – perhaps punishment for lax morals or neglected gods. Seneca, in his treatise, tries to demystify it: earthquakes aren't divine wrath but natural phenomena caused by "air movement" trapped underground, bursting like wind in a bellows. Funny how he compares it to human flatulence – "just as our bodies tremble from belching," so does the earth. Stoic humor at its finest, urging readers not to fear but to understand. "Why be afraid?" he quips. "The earth is just burping."

Yet fear lingered. Some abandoned the area, as Seneca claims, though evidence shows investment surged – a positive feedback loop of reconstruction drawing more people and cash. The Temple of Isis, popular among the Egyptian-influenced crowd, was rebuilt grander, its dedicatory plaque boasting restoration "from the ground up after the earthquake." Public baths got upgrades, the amphitheater reinforced after riots in 59 AD (unrelated, but adding to the town's wild rep). Economically, the quake disrupted trade – the port at Pompeii silted up from landslides, shifting commerce to nearby ports. Agriculture took a hit; those dead sheep signal soil contamination, perhaps reducing yields of the famous Campanian wine.

Zooming out, this event underscores Rome's engineering prowess and bureaucratic muscle. The empire's response – surveying damage, allocating funds, mobilizing workers – mirrors modern disaster relief, minus the helicopters. But it also highlights vulnerabilities: overreliance on slave labor for rebuilds, corruption in contracts (one can imagine shady deals in the rubble), and ignorance of volcanic risks. Vesuvius hadn't erupted in recorded memory, so the quakes were dismissed as isolated nuisances. Hindsight's 20/20, but imagine if they'd connected the dots – poisonous air, frequent shakes, that ominous mountain. Alas, no volcanologists in togas.

Archaeologically, the quake is a boon for dating. Structures showing pre-79 repairs – like the House of the Faun's mosaic floors relaid over cracks – help timeline Pompeii's evolution. Excavations reveal quake-induced modifications: walls thickened, arches added for stability. At Herculaneum, similar patterns emerge, though its burial by mudflows preserved wood and organics better. The bas-reliefs from Iucundus's house? They're like snapshots, showing not just damage but community memory – a way to honor (or exorcise) the trauma.

In the broader tapestry of Roman history, the 62 quake slots into a turbulent era. Nero's reign (54-68 AD) was marked by extravagance, the Great Fire of Rome in 64 (which he blamed on Christians), and political purges. The Campanian disaster added to his woes, though he spun it as an opportunity for imperial benevolence. By 79, under Vespasian and Titus, Pompeii was rebounding – only to be frozen forever. The quake's legacy? It inspired Seneca's scientific inquiry, pushing Roman thought toward rational explanations over myth. And today, it reminds us of nature's caprice: one shake can topple empires, or at least vacation plans.

Fast-forward to our era, and the lessons from this ancient rumble are gold for modern resilience. That Pompeii rebuilt amid ongoing threats shows human tenacity, but also the peril of ignoring warnings. In a world of climate-fueled disasters, applying this historical fact to your life means embracing preparedness without paranoia – turning "what if" into "I've got this."

Diving deeper into the social ripple effects, the quake reshaped Pompeii's society. Wealthy elites poured money into repairs, sparking a building boom that attracted laborers and artisans. Upper-story apartments proliferated to house the influx, turning some streets into proto-apartment blocks. An inscription hints at imperial intervention: a Vespasian-era agent stepping in for economic stabilization. But not everyone bounced back. Slaves and the poor likely bore the brunt, with shoddy tenements collapsing first. And culturally? The quake fueled superstition. Romans saw it as an omen – perhaps punishment for lax morals or neglected gods. Seneca, in his treatise, tries to demystify it: earthquakes aren't divine wrath but natural phenomena caused by "air movement" trapped underground, bursting like wind in a bellows. Funny how he compares it to human flatulence – "just as our bodies tremble from belching," so does the earth. Stoic humor at its finest, urging readers not to fear but to understand. "Why be afraid?" he quips. "The earth is just burping."

Yet fear lingered. Some abandoned the area, as Seneca claims, though evidence shows investment surged – a positive feedback loop of reconstruction drawing more people and cash. The Temple of Isis, popular among the Egyptian-influenced crowd, was rebuilt grander, its dedicatory plaque boasting restoration "from the ground up after the earthquake." Public baths got upgrades, the amphitheater reinforced after riots in 59 AD (unrelated, but adding to the town's wild rep). Economically, the quake disrupted trade – the port at Pompeii silted up from landslides, shifting commerce to nearby ports. Agriculture took a hit; those dead sheep signal soil contamination, perhaps reducing yields of the famous Campanian wine.

Zooming out, this event underscores Rome's engineering prowess and bureaucratic muscle. The empire's response – surveying damage, allocating funds, mobilizing workers – mirrors modern disaster relief, minus the helicopters. But it also highlights vulnerabilities: overreliance on slave labor for rebuilds, corruption in contracts (one can imagine shady deals in the rubble), and ignorance of volcanic risks. Vesuvius hadn't erupted in recorded memory, so the quakes were dismissed as isolated nuisances. Hindsight's 20/20, but imagine if they'd connected the dots – poisonous air, frequent shakes, that ominous mountain. Alas, no volcanologists in togas.

Archaeologically, the quake is a boon for dating. Structures showing pre-79 repairs – like the House of the Faun's mosaic floors relaid over cracks – help timeline Pompeii's evolution. Excavations reveal quake-induced modifications: walls thickened, arches added for stability. At Herculaneum, similar patterns emerge, though its burial by mudflows preserved wood and organics better. The bas-reliefs from Iucundus's house? They're like snapshots, showing not just damage but community memory – a way to honor (or exorcise) the trauma.

In the broader tapestry of Roman history, the 62 quake slots into a turbulent era. Nero's reign (54-68 AD) was marked by extravagance, the Great Fire of Rome in 64 (which he blamed on Christians), and political purges. The Campanian disaster added to his woes, though he spun it as an opportunity for imperial benevolence. By 79, under Vespasian and Titus, Pompeii was rebounding – only to be frozen forever. The quake's legacy? It inspired Seneca's scientific inquiry, pushing Roman thought toward rational explanations over myth. And today, it reminds us of nature's caprice: one shake can topple empires, or at least vacation plans.

Fast-forward to our era, and the lessons from this ancient rumble are gold for modern resilience. That Pompeii rebuilt amid ongoing threats shows human tenacity, but also the peril of ignoring warnings. In a world of climate-fueled disasters, applying this historical fact to your life means embracing preparedness without paranoia – turning "what if" into "I've got this." Here's how you, yes you, can benefit today:

- **Build emotional foundations like Roman walls:** Just as Pompeiians reinforced structures post-quake, strengthen your mental resilience. Start a daily journaling habit: Spend 10 minutes noting three things you're grateful for and one potential "tremor" (stressors) with a plan to handle it. Over time, this creates flexible thinking, reducing panic when life shakes.

- **Assess and retrofit your "personal Pompeii":** Audit your home and habits for vulnerabilities. Create a 72-hour emergency kit with water, non-perishables, a flashlight, and meds – inspired by how Romans fixed aqueducts for water security. Schedule a monthly "quake drill": Practice evacuating your space in under a minute, turning it into a fun family game with rewards.

- **Learn from the "poisonous air" – monitor hidden threats:** Those dead sheep? A metaphor for invisible risks like poor air quality or toxic relationships. Invest in a home CO2 detector or air purifier, and apply it metaphorically: Weekly, evaluate your social circle – cut ties with energy-drainers and nurture supportive ones, boosting your well-being by 20% (per studies on social health).

- **Embrace Seneca's stoicism for motivation:** Channel the philosopher's calm: When facing setbacks, ask, "Is this in my control?" If not, focus on response. Plan: Read a stoic quote daily (apps abound), then apply it – e.g., traffic jam? Use the time for an audiobook on history, turning frustration into education.

- **Foster community reconstruction:** Pompeii's boom post-quake came from collective effort. Join or start a neighborhood preparedness group: Monthly meetups to share skills like first aid or gardening for self-sufficiency. This builds bonds, reducing isolation – stats show connected people recover 30% faster from crises.

The plan: Week 1 – Kit assembly and journaling start. Week 2 – Home audit and drills. Week 3 – Social detox and stoic reading. Week 4 – Community outreach. Repeat quarterly. You'll emerge not just surviving shakes, but thriving – history's ultimate high-five.

Here's how you, yes you, can benefit today:

- **Build emotional foundations like Roman walls:** Just as Pompeiians reinforced structures post-quake, strengthen your mental resilience. Start a daily journaling habit: Spend 10 minutes noting three things you're grateful for and one potential "tremor" (stressors) with a plan to handle it. Over time, this creates flexible thinking, reducing panic when life shakes.

- **Assess and retrofit your "personal Pompeii":** Audit your home and habits for vulnerabilities. Create a 72-hour emergency kit with water, non-perishables, a flashlight, and meds – inspired by how Romans fixed aqueducts for water security. Schedule a monthly "quake drill": Practice evacuating your space in under a minute, turning it into a fun family game with rewards.

- **Learn from the "poisonous air" – monitor hidden threats:** Those dead sheep? A metaphor for invisible risks like poor air quality or toxic relationships. Invest in a home CO2 detector or air purifier, and apply it metaphorically: Weekly, evaluate your social circle – cut ties with energy-drainers and nurture supportive ones, boosting your well-being by 20% (per studies on social health).

- **Embrace Seneca's stoicism for motivation:** Channel the philosopher's calm: When facing setbacks, ask, "Is this in my control?" If not, focus on response. Plan: Read a stoic quote daily (apps abound), then apply it – e.g., traffic jam? Use the time for an audiobook on history, turning frustration into education.

- **Foster community reconstruction:** Pompeii's boom post-quake came from collective effort. Join or start a neighborhood preparedness group: Monthly meetups to share skills like first aid or gardening for self-sufficiency. This builds bonds, reducing isolation – stats show connected people recover 30% faster from crises.

The plan: Week 1 – Kit assembly and journaling start. Week 2 – Home audit and drills. Week 3 – Social detox and stoic reading. Week 4 – Community outreach. Repeat quarterly. You'll emerge not just surviving shakes, but thriving – history's ultimate high-five.

But beneath this vibrant facade lurked a geological time bomb. The Italian peninsula sits on a tectonic tango between the African and Eurasian plates, part of the Apennine mountain chain's ongoing stretch-fest that's been widening the Tyrrhenian Sea for eons. Vesuvius itself is a stratovolcano, born from this subduction zone where one plate dives under another, melting rock into magma that occasionally decides to party on the surface. Historians and geologists now know that the area around the Bay of Naples was no stranger to shakes – minor tremors were as common as bad chariot traffic. But on February 5, 62 AD, things got real. The quake struck with an estimated magnitude between 5.2 and 6.1 on the Richter scale, packing an intensity of IX to X on the Mercalli scale. For the uninitiated, that's "violent" to "extreme" – think buildings crumbling like overbaked biscotti, ground waves visible to the eye, and panic spreading faster than a rumor in the forum. The epicenter? Right smack in the zone of active extensional faulting on Vesuvius's southern flank, involving a messy web of NW-SE and NE-SW oblique-slip normal faults, plus some east-west normals for good measure. The shaking elongated in a west-northwest to east-southeast direction, with a focal depth of about 5-6 kilometers – shallow enough to feel like the underworld was knocking. And knock it did. Eyewitness accounts paint a vivid picture of chaos. The philosopher Seneca the Younger, that stoic sage and advisor to Emperor Nero (more on him later), was quick to document the event in his work *Naturales Quaestiones* (Natural Questions), Book VI, titled *De Terrae Motu* (On Earthquakes). Seneca, ever the intellectual show-off, wasn't just reporting; he was philosophizing. He described how the quake hit during the consulship of Publius Marius and Lucius Afinius Gallus – pinning it firmly to 62 AD, though he initially flubbed the consuls' names in an early draft, leading to some scholarly squabbles over whether it was 62 or 63. (Spoiler: Tacitus, another Roman historian writing decades later, backs 62.) Seneca's account is a goldmine of details, blending science (by ancient standards) with a dash of drama. He notes that the tremor struck in broad daylight, catching everyone off guard. "The earth shook," he writes, "and the sea was driven back, as if the gods had decided to rearrange the landscape." Buildings swayed like drunken sailors, roofs caved in, and statues toppled from their pedestals. In Pompeii, the Temple of Jupiter – that grand centerpiece of the forum, dedicated to the king of the gods himself – partially collapsed, its columns cracking and pediments tumbling. Imagine the irony: Jupiter's house getting wrecked by what many Romans would attribute to his thunderbolts or divine displeasure. The Vesuvius Gate, a key entry point to the city, buckled under the strain, its arches fracturing. The Aquarium of Caesar, possibly a public water feature or bath complex, suffered major damage, with pipes bursting and water flooding streets already choked with debris.

But it wasn't just Pompeii feeling the wrath. Neighboring Herculaneum, a posher seaside retreat for the ultra-rich, took a beating too. Seneca reports that "a large part of the town of Herculaneum fell," with shaky remnants left standing in nearby Nuceria. Even Naples, that bustling port city about 15 miles away, wasn't spared – though its damage was lighter, mostly to private homes and villas, with public buildings holding up better. Villas collapsed in the countryside, and widespread tremors rippled through the region without always causing total ruin. One bizarre detail from Seneca: 600 sheep perished, not from falling rubble, but from "poisonous air" that tainted the atmosphere. Was this an early whiff of volcanic gases seeping from Vesuvius? Modern geologists think so – sulfurous fumes or carbon dioxide releases could have asphyxiated livestock, hinting that the quake was tied to magmatic stirrings deep below. It's like nature's subtle spoiler alert for the 79 AD blockbuster. Human casualties? The ancient sources are frustratingly vague – no neat body counts like in modern disaster reports. But extrapolating from the scale, deaths likely numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands, across the region. Some folks, traumatized by the ordeal, "started to wander about, unable to regain control over themselves," as Seneca puts it. Picture shell-shocked survivors stumbling through rubble-strewn streets, their world literally upended. Tacitus, in his *Annals*, gives a curt nod: "An earthquake demolished a large part of Pompeii, a populous town in Campania." Brevity is the soul of wit, but here it's the soul of understatement. Archaeological evidence fills in the gaps where words fail. Excavations at Pompeii reveal telltale signs: cracked walls patched with hasty repairs, floors relaid over subsidence craters, and buildings mid-renovation when the volcano hit in 79. One standout artifact? The bas-reliefs from the House of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, a wealthy banker whose lararium (household shrine) featured carved stone panels depicting the quake's havoc. One shows the Temple of Jupiter teetering, another the Vesuvius Gate askew – like ancient disaster selfies, capturing the moment for posterity. Tragically, Iucundus himself may have perished in the quake; his house shows signs of abandonment post-62.

The aftermath was a masterclass in Roman resilience – or hubris, depending on your view. Reconstruction kicked off almost immediately, fueled by imperial aid and private fortunes. Emperor Nero, that flamboyant fiddle-player (though the fiddle story's a myth), sent relief funds and engineers. By some accounts, he even visited the area, though a later quake in 64 AD during one of his performances in Naples added a theatrical twist – the theater shook as he sang, which he took as applause from the gods. (Nero being Nero, he probably bowed.) In Pompeii, the forum was revamped, temples rebuilt with sturdier materials, and aqueducts reinforced. The Serino Aqueduct, which piped fresh water from the mountains, needed major fixes after fractures caused widespread shortages. Streets were repaved, homes retrofitted with anti-seismic designs like lighter roofs and flexible joints – early earthquake engineering, Roman style. But here's the kicker: the rebuilding wasn't done by 79 AD. When Vesuvius erupted, Pompeii was still a construction zone. Scaffolding dotted temples, trenches scarred roads for pipe repairs, and some villas lay in ruins, their owners perhaps having fled after repeated aftershocks. Yes, the 62 quake wasn't a one-off. Scholars now believe it ushered in a swarm of seismic activity – smaller tremors plaguing the region for years. Pliny the Younger, in his letters describing the 79 eruption, mentions "earth tremors which were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania." Frequent? That's like saying Italian traffic is "lively." A quake in 64 AD rattled Nero's show in Naples, and ongoing shakes kept nerves frayed. Geologists link this to Vesuvius waking up after centuries of dormancy. The 62 quake may have fractured the crust, allowing magma to rise, pressurizing the system like a shaken soda bottle. By 79, pop went the volcano, burying Pompeii under 4-6 meters of ash and pumice, preserving it as a time capsule.

Diving deeper into the social ripple effects, the quake reshaped Pompeii's society. Wealthy elites poured money into repairs, sparking a building boom that attracted laborers and artisans. Upper-story apartments proliferated to house the influx, turning some streets into proto-apartment blocks. An inscription hints at imperial intervention: a Vespasian-era agent stepping in for economic stabilization. But not everyone bounced back. Slaves and the poor likely bore the brunt, with shoddy tenements collapsing first. And culturally? The quake fueled superstition. Romans saw it as an omen – perhaps punishment for lax morals or neglected gods. Seneca, in his treatise, tries to demystify it: earthquakes aren't divine wrath but natural phenomena caused by "air movement" trapped underground, bursting like wind in a bellows. Funny how he compares it to human flatulence – "just as our bodies tremble from belching," so does the earth. Stoic humor at its finest, urging readers not to fear but to understand. "Why be afraid?" he quips. "The earth is just burping." Yet fear lingered. Some abandoned the area, as Seneca claims, though evidence shows investment surged – a positive feedback loop of reconstruction drawing more people and cash. The Temple of Isis, popular among the Egyptian-influenced crowd, was rebuilt grander, its dedicatory plaque boasting restoration "from the ground up after the earthquake." Public baths got upgrades, the amphitheater reinforced after riots in 59 AD (unrelated, but adding to the town's wild rep). Economically, the quake disrupted trade – the port at Pompeii silted up from landslides, shifting commerce to nearby ports. Agriculture took a hit; those dead sheep signal soil contamination, perhaps reducing yields of the famous Campanian wine. Zooming out, this event underscores Rome's engineering prowess and bureaucratic muscle. The empire's response – surveying damage, allocating funds, mobilizing workers – mirrors modern disaster relief, minus the helicopters. But it also highlights vulnerabilities: overreliance on slave labor for rebuilds, corruption in contracts (one can imagine shady deals in the rubble), and ignorance of volcanic risks. Vesuvius hadn't erupted in recorded memory, so the quakes were dismissed as isolated nuisances. Hindsight's 20/20, but imagine if they'd connected the dots – poisonous air, frequent shakes, that ominous mountain. Alas, no volcanologists in togas. Archaeologically, the quake is a boon for dating. Structures showing pre-79 repairs – like the House of the Faun's mosaic floors relaid over cracks – help timeline Pompeii's evolution. Excavations reveal quake-induced modifications: walls thickened, arches added for stability. At Herculaneum, similar patterns emerge, though its burial by mudflows preserved wood and organics better. The bas-reliefs from Iucundus's house? They're like snapshots, showing not just damage but community memory – a way to honor (or exorcise) the trauma. In the broader tapestry of Roman history, the 62 quake slots into a turbulent era. Nero's reign (54-68 AD) was marked by extravagance, the Great Fire of Rome in 64 (which he blamed on Christians), and political purges. The Campanian disaster added to his woes, though he spun it as an opportunity for imperial benevolence. By 79, under Vespasian and Titus, Pompeii was rebounding – only to be frozen forever. The quake's legacy? It inspired Seneca's scientific inquiry, pushing Roman thought toward rational explanations over myth. And today, it reminds us of nature's caprice: one shake can topple empires, or at least vacation plans. Fast-forward to our era, and the lessons from this ancient rumble are gold for modern resilience. That Pompeii rebuilt amid ongoing threats shows human tenacity, but also the peril of ignoring warnings. In a world of climate-fueled disasters, applying this historical fact to your life means embracing preparedness without paranoia – turning "what if" into "I've got this."

Here's how you, yes you, can benefit today: - **Build emotional foundations like Roman walls:** Just as Pompeiians reinforced structures post-quake, strengthen your mental resilience. Start a daily journaling habit: Spend 10 minutes noting three things you're grateful for and one potential "tremor" (stressors) with a plan to handle it. Over time, this creates flexible thinking, reducing panic when life shakes. - **Assess and retrofit your "personal Pompeii":** Audit your home and habits for vulnerabilities. Create a 72-hour emergency kit with water, non-perishables, a flashlight, and meds – inspired by how Romans fixed aqueducts for water security. Schedule a monthly "quake drill": Practice evacuating your space in under a minute, turning it into a fun family game with rewards. - **Learn from the "poisonous air" – monitor hidden threats:** Those dead sheep? A metaphor for invisible risks like poor air quality or toxic relationships. Invest in a home CO2 detector or air purifier, and apply it metaphorically: Weekly, evaluate your social circle – cut ties with energy-drainers and nurture supportive ones, boosting your well-being by 20% (per studies on social health). - **Embrace Seneca's stoicism for motivation:** Channel the philosopher's calm: When facing setbacks, ask, "Is this in my control?" If not, focus on response. Plan: Read a stoic quote daily (apps abound), then apply it – e.g., traffic jam? Use the time for an audiobook on history, turning frustration into education. - **Foster community reconstruction:** Pompeii's boom post-quake came from collective effort. Join or start a neighborhood preparedness group: Monthly meetups to share skills like first aid or gardening for self-sufficiency. This builds bonds, reducing isolation – stats show connected people recover 30% faster from crises. The plan: Week 1 – Kit assembly and journaling start. Week 2 – Home audit and drills. Week 3 – Social detox and stoic reading. Week 4 – Community outreach. Repeat quarterly. You'll emerge not just surviving shakes, but thriving – history's ultimate high-five.