Part I: The Geography of Destiny and the Furnace of Antiquity

The Volcanic Sentinel

To understand the events of January 19, 1839, one must first understand the ground upon which they transpired—a terrain so hostile, so geographically distinctive, and so strategically inevitable that it seems forged by the earth itself for the specific purpose of conflict and commerce. Aden is not merely a port; it is a geological fortress. Located on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, in what is today the Republic of Yemen, the peninsula is dominated by the jagged, blackened remnants of an extinct volcano. The Crater, as the heart of the old settlement is known, sits within the collapsed caldera of this ancient titan, surrounded by walls of igneous rock that rise sheer and forbidding from the sea. This geography is destiny. For millennia, long before the British East India Company turned its covetous gaze toward the Red Sea, Aden served as the "Eye of Yemen." It stands at the confluence of the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea. It guards the Bab-el-Mandeb—the "Gate of Tears"—the narrow strait that separates Africa from Arabia. Whoever controls Aden controls the flow of trade between the Mediterranean and the East. The Romans knew this, calling it Eudaemon Arabia (Happy Arabia). The Ottomans knew this, seizing it in 1538 to check the Portuguese expansion in the Indian Ocean. And by the 1830s, the British Empire, fueled by the fires of the Industrial Revolution, knew it with a desperate, burning certainty.

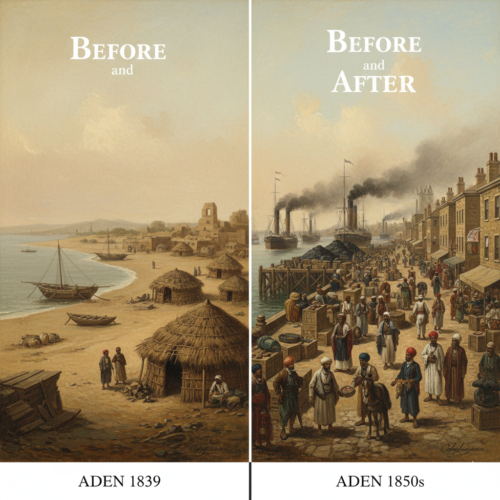

The landscape of Aden in the early 19th century was a study in contrasts. To the mariner, the dramatic skyline of Jebel Shamsan—the highest peak of the crater—offered a navigational beacon visible for miles. The natural harbor, known as the Back Bay (later Aden Harbour) and Front Bay, provided shelter even during the fiercest monsoons. Yet, to the inhabitant, it was a waterless, sun-scorched rock. The ancient cisterns, carved into the rock to catch the rare torrential rains, had fallen into disrepair. The settlement, once a thriving emporium of thousands, had dwindled under the rule of the Abdali Sultans of Lahej to a squalid fishing village of barely 600 souls—Arabs, Somalis, Jews, and Banyans living in huts of reed matting amidst the ruins of stone palaces.

It was here, on this desolate cinder of a peninsula, that the Victorian age would make its first definitive, violent mark on the map of the Middle East. The capture of Aden was not an isolated skirmish; it was the tectonic collision of two eras. It was the moment where the Age of Sail, represented by the dhows and reliance on trade winds, was brutally superseded by the Age of Steam. The British did not take Aden for gold, spices, or territory in the traditional sense. They took it because a new beast had been born in the shipyards of Britain—the steamship—and that beast had a voracious, insatiable appetite for coal.

The Steam Imperative and the tyranny of Logistics

The backstory of January 19, 1839, is written in soot and steam. By the 1830s, the communication lines between London and Bombay were stretched to the breaking point. The traditional route via the Cape of Good Hope was a grueling odyssey that could take four to six months. A letter sent from Calcutta might not receive a reply for two years. For an empire that relied on information—market prices, troop movements, political intelligence—this lag was intolerable.

The solution lay in the "Overland Route" through Egypt and the Red Sea. A steamship could travel from Bombay to Suez, passengers could cross the desert to Alexandria, and another ship could carry them to Europe. This route promised to cut the journey in half. But early steamships were inefficient. They were paddle-wheelers that guzzled coal at a prodigious rate. A steamer like the Hugh Lindsay, which made the pioneering voyage in 1830, could not carry enough fuel to cross the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea in one leg. They needed "gas stations" of the sea—coaling depots where they could restock.

This logistical reality transformed the barren rocks of the Arabian coast into the most valuable real estate in the empire. The East India Company (EIC) initially looked to the island of Socotra. It sat at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden. Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines, a brilliant and ambitious surveyor of the Indian Navy, was sent to map it and acquire it. But Socotra proved a failure. It lacked a secure harbor, was ravaged by fevers, and was battered by monsoons that made coaling dangerous.

Haines, with the surveyor's eye for topography and the strategist's eye for war, turned his attention to Aden. He saw what the Board of Directors in Bombay could not: Aden was the perfect fortress. Its harbor was defended by nature. Its position was unassailable. If the British did not take it, others would. The Egyptians, under the expansionist Muhammad Ali Pasha, were marching down the Arabian coast. The Americans and French were sniffing around the Red Sea. The race for the "Coal Hole of the East" was on, and Haines was determined to win it.

Part II: The Pretext – The Tragedy of the Doria Dowlut

A Cargo of Riches and Pilgrims

History often turns on the fate of a single ship. In the case of Aden, that ship was the Doria Dowlut. She was a barque of 225 tons, flying the British flag—a crucial legal detail—and owned by the Begum Ahmed Nissa, the mother of the Nawab of Madras. In early 1837, she was sailing from Calcutta to Jeddah, carrying a cargo that evokes the richness of the Indian Ocean trade: Bengali textiles, Kinkaub (gold-embroidered cloth), Chinese satin, rose perfume, ginger, pepper, and iron.

But the Doria Dowlut carried something more precious than spices: pilgrims. The ship was laden with Muslim devotees bound for the Hajj in Mecca. Among them were wealthy merchants and their families, carrying their life savings in gold and jewelry.

On the dark morning of February 20, 1837, the Doria Dowlut drifted into the waters off Aden. Whether by treacherous currents or, as Captain Haines would later allege, the treachery of a pilot paid to run her aground, the vessel struck the seabed about four miles northeast of the peninsula.

The Plunder and the Insult

What happened next shifted the incident from a maritime tragedy to a casus belli. The ship did not break apart immediately. As she listed in the surf, she was spotted by the Abdali tribesmen of Aden. In the ethos of the coast, a wreck was a gift from God. But the Doria Dowlut was under British protection, and the response of the locals went far beyond salvage.

The depositions taken by British agents paint a harrowing picture of the chaotic hours that followed. Skiffs launched from the shore, not to rescue the drowning pilgrims, but to strip them. The cargo was hauled away—rice, sugar, and the precious textiles disappeared into the storehouses of the Sultan of Lahej. The human cost was far uglier. Survivors reported that the Bedouin plunderers stripped women naked to search for gold hidden in their clothes. The ship’s captain, Nakhooda Syed Nouradeen, testified that he was held underwater by his beard and tortured until he revealed the location of the ship’s specie.

This geography is destiny. For millennia, long before the British East India Company turned its covetous gaze toward the Red Sea, Aden served as the "Eye of Yemen." It stands at the confluence of the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea. It guards the Bab-el-Mandeb—the "Gate of Tears"—the narrow strait that separates Africa from Arabia. Whoever controls Aden controls the flow of trade between the Mediterranean and the East. The Romans knew this, calling it Eudaemon Arabia (Happy Arabia). The Ottomans knew this, seizing it in 1538 to check the Portuguese expansion in the Indian Ocean. And by the 1830s, the British Empire, fueled by the fires of the Industrial Revolution, knew it with a desperate, burning certainty.

The landscape of Aden in the early 19th century was a study in contrasts. To the mariner, the dramatic skyline of Jebel Shamsan—the highest peak of the crater—offered a navigational beacon visible for miles. The natural harbor, known as the Back Bay (later Aden Harbour) and Front Bay, provided shelter even during the fiercest monsoons. Yet, to the inhabitant, it was a waterless, sun-scorched rock. The ancient cisterns, carved into the rock to catch the rare torrential rains, had fallen into disrepair. The settlement, once a thriving emporium of thousands, had dwindled under the rule of the Abdali Sultans of Lahej to a squalid fishing village of barely 600 souls—Arabs, Somalis, Jews, and Banyans living in huts of reed matting amidst the ruins of stone palaces.

It was here, on this desolate cinder of a peninsula, that the Victorian age would make its first definitive, violent mark on the map of the Middle East. The capture of Aden was not an isolated skirmish; it was the tectonic collision of two eras. It was the moment where the Age of Sail, represented by the dhows and reliance on trade winds, was brutally superseded by the Age of Steam. The British did not take Aden for gold, spices, or territory in the traditional sense. They took it because a new beast had been born in the shipyards of Britain—the steamship—and that beast had a voracious, insatiable appetite for coal.

The Steam Imperative and the tyranny of Logistics

The backstory of January 19, 1839, is written in soot and steam. By the 1830s, the communication lines between London and Bombay were stretched to the breaking point. The traditional route via the Cape of Good Hope was a grueling odyssey that could take four to six months. A letter sent from Calcutta might not receive a reply for two years. For an empire that relied on information—market prices, troop movements, political intelligence—this lag was intolerable.

The solution lay in the "Overland Route" through Egypt and the Red Sea. A steamship could travel from Bombay to Suez, passengers could cross the desert to Alexandria, and another ship could carry them to Europe. This route promised to cut the journey in half. But early steamships were inefficient. They were paddle-wheelers that guzzled coal at a prodigious rate. A steamer like the Hugh Lindsay, which made the pioneering voyage in 1830, could not carry enough fuel to cross the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea in one leg. They needed "gas stations" of the sea—coaling depots where they could restock.

This logistical reality transformed the barren rocks of the Arabian coast into the most valuable real estate in the empire. The East India Company (EIC) initially looked to the island of Socotra. It sat at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden. Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines, a brilliant and ambitious surveyor of the Indian Navy, was sent to map it and acquire it. But Socotra proved a failure. It lacked a secure harbor, was ravaged by fevers, and was battered by monsoons that made coaling dangerous.

Haines, with the surveyor's eye for topography and the strategist's eye for war, turned his attention to Aden. He saw what the Board of Directors in Bombay could not: Aden was the perfect fortress. Its harbor was defended by nature. Its position was unassailable. If the British did not take it, others would. The Egyptians, under the expansionist Muhammad Ali Pasha, were marching down the Arabian coast. The Americans and French were sniffing around the Red Sea. The race for the "Coal Hole of the East" was on, and Haines was determined to win it.

Part II: The Pretext – The Tragedy of the Doria Dowlut

A Cargo of Riches and Pilgrims

History often turns on the fate of a single ship. In the case of Aden, that ship was the Doria Dowlut. She was a barque of 225 tons, flying the British flag—a crucial legal detail—and owned by the Begum Ahmed Nissa, the mother of the Nawab of Madras. In early 1837, she was sailing from Calcutta to Jeddah, carrying a cargo that evokes the richness of the Indian Ocean trade: Bengali textiles, Kinkaub (gold-embroidered cloth), Chinese satin, rose perfume, ginger, pepper, and iron.

But the Doria Dowlut carried something more precious than spices: pilgrims. The ship was laden with Muslim devotees bound for the Hajj in Mecca. Among them were wealthy merchants and their families, carrying their life savings in gold and jewelry.

On the dark morning of February 20, 1837, the Doria Dowlut drifted into the waters off Aden. Whether by treacherous currents or, as Captain Haines would later allege, the treachery of a pilot paid to run her aground, the vessel struck the seabed about four miles northeast of the peninsula.

The Plunder and the Insult

What happened next shifted the incident from a maritime tragedy to a casus belli. The ship did not break apart immediately. As she listed in the surf, she was spotted by the Abdali tribesmen of Aden. In the ethos of the coast, a wreck was a gift from God. But the Doria Dowlut was under British protection, and the response of the locals went far beyond salvage.

The depositions taken by British agents paint a harrowing picture of the chaotic hours that followed. Skiffs launched from the shore, not to rescue the drowning pilgrims, but to strip them. The cargo was hauled away—rice, sugar, and the precious textiles disappeared into the storehouses of the Sultan of Lahej. The human cost was far uglier. Survivors reported that the Bedouin plunderers stripped women naked to search for gold hidden in their clothes. The ship’s captain, Nakhooda Syed Nouradeen, testified that he was held underwater by his beard and tortured until he revealed the location of the ship’s specie. When the battered survivors finally reached the shore, they were not offered hospitality but were further exploited. Eventually, they made their way to Mocha, where they encountered Captain Stafford Haines. Haines, ever the diligent officer, took their depositions. He saw the genuine trauma in their accounts—the robbery, the rape, the bribery, and the manslaughter.

But Haines also saw something else. He saw the "Insult to the Flag." In the diplomatic language of the 19th century, the mistreatment of a ship flying British colors was an attack on the sovereignty of the Crown itself. It provided the moral and legal leverage the East India Company needed. The Doria Dowlut affair gave the British a justification that went beyond mere coal. They could now cloak their strategic ambition in the righteous robes of justice and protection.

The Diplomatic Dance of Deception

Haines was dispatched to Aden in the sloop Coote to demand reparations. He carried a bill for 12,000 Maria Theresa Thalers (the currency of the region) for the stolen cargo. But his secret instructions were clear: if the Sultan could not pay—and everyone knew he could not—Haines was authorized to accept the cession of Aden to the British Crown in lieu of payment.

For nearly a year, a tense game of cat and mouse played out between Captain Haines and Sultan Muhsin bin Fadl of Lahej. Sultan Muhsin was an aging, wily ruler, struggling to maintain his authority over unruly tribes and greedy sons. He knew the British were dangerous, but he also feared losing his sovereignty.

The negotiations were a masterclass in frustration. The Sultan would agree to sell the peninsula one day, then renege the next. He claimed his seal had been stolen. He claimed his sons refused to agree. At one point, his son Hamed attempted to kidnap Haines during a meeting to force him to drop the demands. Haines, displaying the icy nerve that would characterize his career, escaped the trap.

The situation deteriorated. The Sultan sent letters of friendship while his soldiers reinforced the fortifications on Sira Island. On December 13, 1838, the pretense of diplomacy shattered. Arab soldiers on the shore fired muskets at the Coote’s boats. Haines, seizing the moment, declared this an act of war. He instituted a blockade and sent word to Bombay: the time for talking was over. The "Eye of Yemen" would have to be taken by fire.

Part III: The Armada Assembles – Order of Battle

The Naval Hammer

The Government of Bombay, led by Governor Robert Grant, authorized the expedition. This was not to be a punitive raid; it was a conquest. The force assembled was overwhelming for the time and place, a mix of the Royal Navy’s global reach and the Indian Navy’s local expertise.

The Naval Squadron:

When the battered survivors finally reached the shore, they were not offered hospitality but were further exploited. Eventually, they made their way to Mocha, where they encountered Captain Stafford Haines. Haines, ever the diligent officer, took their depositions. He saw the genuine trauma in their accounts—the robbery, the rape, the bribery, and the manslaughter.

But Haines also saw something else. He saw the "Insult to the Flag." In the diplomatic language of the 19th century, the mistreatment of a ship flying British colors was an attack on the sovereignty of the Crown itself. It provided the moral and legal leverage the East India Company needed. The Doria Dowlut affair gave the British a justification that went beyond mere coal. They could now cloak their strategic ambition in the righteous robes of justice and protection.

The Diplomatic Dance of Deception

Haines was dispatched to Aden in the sloop Coote to demand reparations. He carried a bill for 12,000 Maria Theresa Thalers (the currency of the region) for the stolen cargo. But his secret instructions were clear: if the Sultan could not pay—and everyone knew he could not—Haines was authorized to accept the cession of Aden to the British Crown in lieu of payment.

For nearly a year, a tense game of cat and mouse played out between Captain Haines and Sultan Muhsin bin Fadl of Lahej. Sultan Muhsin was an aging, wily ruler, struggling to maintain his authority over unruly tribes and greedy sons. He knew the British were dangerous, but he also feared losing his sovereignty.

The negotiations were a masterclass in frustration. The Sultan would agree to sell the peninsula one day, then renege the next. He claimed his seal had been stolen. He claimed his sons refused to agree. At one point, his son Hamed attempted to kidnap Haines during a meeting to force him to drop the demands. Haines, displaying the icy nerve that would characterize his career, escaped the trap.

The situation deteriorated. The Sultan sent letters of friendship while his soldiers reinforced the fortifications on Sira Island. On December 13, 1838, the pretense of diplomacy shattered. Arab soldiers on the shore fired muskets at the Coote’s boats. Haines, seizing the moment, declared this an act of war. He instituted a blockade and sent word to Bombay: the time for talking was over. The "Eye of Yemen" would have to be taken by fire.

Part III: The Armada Assembles – Order of Battle

The Naval Hammer

The Government of Bombay, led by Governor Robert Grant, authorized the expedition. This was not to be a punitive raid; it was a conquest. The force assembled was overwhelming for the time and place, a mix of the Royal Navy’s global reach and the Indian Navy’s local expertise.

The Naval Squadron:

HMS Volage: The flagship. A 28-gun Sixth Rate frigate of the Royal Navy, commanded by Captain Henry Smith. The Volage was the heavy hitter, armed with 32-pounder carronades capable of smashing stone fortifications to rubble. Her presence signaled that this was a Crown affair, not just a Company squabble.

HMS Cruizer: An 18-gun brig-sloop, commanded by Commander King. Fast and maneuverable, she acted as the supporting hammer to the Volage's anvil.

HCS Coote: An 18-gun sloop of war belonging to the Honorable East India Company (HEIC), commanded by Captain Denton. This was Haines’s ship, the center of political intelligence.

HCS Mahi: A 5-gun schooner, commanded by Lieutenant Daniell. Her shallow draft allowed her to skirt the reefs and flank the enemy batteries.

Transports: The Lowjee Family and the Ernaad carried the troops, ammunition, and coal.

The Landing Force

The soldiers chosen for the assault reflected the cosmopolitan nature of the British Raj. They were a mix of European discipline and Sepoy resilience, numbering approximately 700 bayonets.

The Royal Marines: The elite sea-soldiers, disciplined and deadly in amphibious assaults.

The 24th Bombay Native Infantry: A regiment of Indian Sepoys, hardened by campaigns on the subcontinent. They were commanded by Major Baillie, a veteran officer.

The Bombay European Regiment: The Company’s "private" European troops, known for their toughness.

The Bombay Artillery: Specialists with 12-pounder cannons and howitzers, essential for breaching the Sultan’s palace.

Against them stood the Sultan’s garrison. They numbered around 1,000 men, a mix of Abdali tribesmen and mercenaries. They held the Fortress of Sira, a triangular rock island connected to the mainland by a causeway, fortified with stone breastworks and towering batteries. They possessed 33 pieces of artillery, mostly antiquated bronze guns from the Ottoman era, and were armed with matchlocks and jambiyas (curved daggers). They were brave, fierce, and utterly outclassed by the industrial firepower bearing down on them.

Part IV: The Day of Fire – January 19, 1839

The Approach

The morning of January 19, 1839, dawned with the crisp clarity of the Arabian winter. The sea was calm, the monsoon winds having settled. Captain Henry Smith, aboard the Volage, signaled the fleet to advance. The plan was a direct, brutal assault: the ships would sail into Front Bay, anchor at point-blank range to the Sira fortifications, and silence the guns. Only then would the troops land.

As the great white sails of the British ships filled with the breeze, the Arab defenders on Sira Island watched them come. At 9:30 AM, as the Volage closed the distance, the Arab batteries opened fire. Puffs of white smoke bloomed from the dark volcanic rock. Round shot splashed into the water around the frigates, some cutting through rigging or thumping harmlessly against the thick oak hulls.

The British held their fire. Captain Smith maneuvered the Volage with icy precision, bringing her broadside to bear on the lower battery of Sira. The Cruizer took up station on her stern. The Mahi darted to the flank to rake the enemy cover.

The Bombardment

At the signal, the British ships erupted. The Volage unleashed a broadside of iron. The sound was cataclysmic, rolling off the crater walls like thunder. The 32-pound shots smashed into the stone breastworks of Sira, disintegrating masonry and sending shrapnel tearing through the Arab positions. For nearly two hours, the bay was choked with sulfurous smoke. The British gunnery was relentless and disciplined. They systematically dismantled the defenses. The great tower on Sira Island, which had stood for centuries, crumbled under the weight of the barrage. The Arab return fire, initially spirited, began to slacken as their guns were dismounted and their gunners killed or driven into the rocks.

Captain Haines, watching from the Coote, noted the devastation. The "modern" war machine of Europe was dismantling the medieval defenses of Arabia with terrifying efficiency.

The Storming of Sira

By 11:00 AM, the enemy fire had been silenced. The signal to land was hoisted. The boats were lowered from the Lowjee Family and the Ernaad. Major Baillie led the 24th Bombay Native Infantry and the Europeans into the pinnaces.

They rowed hard for the shore, oars dipping in unison. As the keels crunched onto the sand, the troops vaulted over the gunwales, bayonets fixed. A scattered, desperate musketry erupted from the ruins, but the British charge was unstoppable.

Captain Smith landed with a party of seamen and Marines from the Volage to storm the Sira fortress directly. They fought their way up the causeway, engaging in vicious hand-to-hand combat with the surviving defenders who refused to surrender. The disciplined bayonet drills of the Marines overcame the desperate courage of the tribesmen.

They reached the summit of Sira. The Sultan’s red flag was still flying. A British sailor shinned up the pole, tore it down, and hoisted the Union Jack. It was the first time the British flag would fly over a colony in Queen Victoria’s reign.

The Capture of the Town

With the fortress taken, the troops advanced into Aden town. They found it largely deserted; the women and children had been evacuated to the interior. The Sultan’s palace was stormed and secured. By the afternoon, the shooting had stopped.

The casualty count told the story of technological asymmetry. The British had lost no men killed in action during the assault, though 15 to 17 were wounded (some later died of wounds). The Arab defenders had suffered heavily: over 150 killed and wounded. The British captured 139 prisoners and all 33 guns.

Haines stood amidst the ruins of the town. The "Eye of Yemen" was theirs. The strategic pivot of the Indian Ocean had been seized for the price of a few dozen casualties and a morning’s worth of gunpowder.

Part V: The Anchor of Empire – Building the Coal Hole

The Transformation

The conquest was only the beginning. Captain Haines was appointed the first Political Agent of Aden, a post he would hold for fifteen years. He found a ruin; he built a metropolis.

Haines understood that for Aden to succeed, it had to be more than a fortress; it had to be a market. He declared Aden a "Free Port" in 1850, abolishing the customs duties that choked trade in other Red Sea ports like Mocha. He invited merchants from India—Parsees, Banyans, and Borahs—to settle, offering them land and protection. He encouraged the Jewish community of Aden to rebuild their lives free from the persecution of the Sultans.

The results were miraculous. The population exploded from 600 in 1839 to over 20,000 by the mid-1850s. The harbor was dredged and fortified. Huge coal depots were constructed, fed by colliers from Wales. Aden became the lifeblood of the Empire. Every P&O steamer carrying mail, officials, or troops to India stopped at Aden. It became a "Little London" on the Arabian coast, a place of clubs, churches, and commerce.

For nearly two hours, the bay was choked with sulfurous smoke. The British gunnery was relentless and disciplined. They systematically dismantled the defenses. The great tower on Sira Island, which had stood for centuries, crumbled under the weight of the barrage. The Arab return fire, initially spirited, began to slacken as their guns were dismounted and their gunners killed or driven into the rocks.

Captain Haines, watching from the Coote, noted the devastation. The "modern" war machine of Europe was dismantling the medieval defenses of Arabia with terrifying efficiency.

The Storming of Sira

By 11:00 AM, the enemy fire had been silenced. The signal to land was hoisted. The boats were lowered from the Lowjee Family and the Ernaad. Major Baillie led the 24th Bombay Native Infantry and the Europeans into the pinnaces.

They rowed hard for the shore, oars dipping in unison. As the keels crunched onto the sand, the troops vaulted over the gunwales, bayonets fixed. A scattered, desperate musketry erupted from the ruins, but the British charge was unstoppable.

Captain Smith landed with a party of seamen and Marines from the Volage to storm the Sira fortress directly. They fought their way up the causeway, engaging in vicious hand-to-hand combat with the surviving defenders who refused to surrender. The disciplined bayonet drills of the Marines overcame the desperate courage of the tribesmen.

They reached the summit of Sira. The Sultan’s red flag was still flying. A British sailor shinned up the pole, tore it down, and hoisted the Union Jack. It was the first time the British flag would fly over a colony in Queen Victoria’s reign.

The Capture of the Town

With the fortress taken, the troops advanced into Aden town. They found it largely deserted; the women and children had been evacuated to the interior. The Sultan’s palace was stormed and secured. By the afternoon, the shooting had stopped.

The casualty count told the story of technological asymmetry. The British had lost no men killed in action during the assault, though 15 to 17 were wounded (some later died of wounds). The Arab defenders had suffered heavily: over 150 killed and wounded. The British captured 139 prisoners and all 33 guns.

Haines stood amidst the ruins of the town. The "Eye of Yemen" was theirs. The strategic pivot of the Indian Ocean had been seized for the price of a few dozen casualties and a morning’s worth of gunpowder.

Part V: The Anchor of Empire – Building the Coal Hole

The Transformation

The conquest was only the beginning. Captain Haines was appointed the first Political Agent of Aden, a post he would hold for fifteen years. He found a ruin; he built a metropolis.

Haines understood that for Aden to succeed, it had to be more than a fortress; it had to be a market. He declared Aden a "Free Port" in 1850, abolishing the customs duties that choked trade in other Red Sea ports like Mocha. He invited merchants from India—Parsees, Banyans, and Borahs—to settle, offering them land and protection. He encouraged the Jewish community of Aden to rebuild their lives free from the persecution of the Sultans.

The results were miraculous. The population exploded from 600 in 1839 to over 20,000 by the mid-1850s. The harbor was dredged and fortified. Huge coal depots were constructed, fed by colliers from Wales. Aden became the lifeblood of the Empire. Every P&O steamer carrying mail, officials, or troops to India stopped at Aden. It became a "Little London" on the Arabian coast, a place of clubs, churches, and commerce. The Fortification of the Hinterland

But the Sultan of Lahej did not give up. Stung by the loss of his revenue, he launched repeated attacks on the settlement in 1840 and 1846, trying to drive the "infidels" into the sea. Haines responded by building a massive defensive wall across the isthmus—the "Turkish Wall"—and cultivating a network of spies among the tribes. He used a "divide and rule" strategy, paying stipends to friendly sheikhs while punishing hostiles with artillery.

Part VI: The Tragedy of Stafford Haines – The Martyr of Bureaucracy

The Visionary's Fall

There is a bitter irony at the heart of the Aden story. Stafford Haines, the man who gave Britain the key to the East, was destroyed by the very empire he served. Haines was a "man on the spot"—a proactive, independent operator who did what was necessary to survive on a hostile frontier. He paid bribes, hired spies, and spent money on fortifications without waiting for the slow, agonizing approval of the Bombay bureaucracy.

He kept records, but they were the records of a soldier, not an accountant. In 1854, the East India Company, looking to cut costs, sent auditors to Aden. They found a deficit of £28,000 in the treasury. There was no evidence Haines had stolen the money for personal gain—he lived modestly and died poor—but he could not produce the receipts to prove where it had gone.

The Company was unforgiving. They recalled him to Bombay in chains. He was put on trial for fraud and embezzlement. Twice, juries of his peers acquitted him, recognizing his service and integrity. But the Governor of Bombay, Lord Elphinstone, used a loophole in civil law to demand repayment of the £28,000.

Death in the Debtor's Prison

Haines, with his captain's salary, could never repay such a sum. He was thrown into a debtor's prison in Bombay. For six years, the conqueror of Aden rotted in a hot, squalid cell. He watched from his barred window as the ships he had facilitated—the steamers carrying the wealth of India—sailed in and out of the harbor.

His health collapsed. His spirit broke. Finally, in 1860, a new governor, Sir George Clerk, visited the prison and was horrified to find the Empire's hero in such a state. He ordered Haines' immediate release.

Haines stumbled out of prison, a broken old man. He boarded a ship bound for England, hoping to see the white cliffs one last time. He never made it. He died one week later, on June 16, 1860, while the ship was still in Bombay harbor.

The Legacy

Haines died a "criminal," but history vindicated him. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened. Aden instantly became one of the most important ports in the world, the "Gibraltar of the East". It served as the strategic anchor for British power in the Middle East until 1967. The telegraph cables that linked London to Bombay ran through Aden. The coal that fueled the Royal Navy was stacked on its wharves. Haines' vision had reshaped the world, even if the world had crushed him.

Part VII: Strategic Analysis – Data and Logistics

To fully grasp the magnitude of the operation and the strategic value of Aden, we must look at the data. The following tables illustrate the military disparity and the logistical triumph of the Aden acquisition.

Table 1: Comparative Strength - Battle of Aden (Jan 19, 1839)

The Fortification of the Hinterland

But the Sultan of Lahej did not give up. Stung by the loss of his revenue, he launched repeated attacks on the settlement in 1840 and 1846, trying to drive the "infidels" into the sea. Haines responded by building a massive defensive wall across the isthmus—the "Turkish Wall"—and cultivating a network of spies among the tribes. He used a "divide and rule" strategy, paying stipends to friendly sheikhs while punishing hostiles with artillery.

Part VI: The Tragedy of Stafford Haines – The Martyr of Bureaucracy

The Visionary's Fall

There is a bitter irony at the heart of the Aden story. Stafford Haines, the man who gave Britain the key to the East, was destroyed by the very empire he served. Haines was a "man on the spot"—a proactive, independent operator who did what was necessary to survive on a hostile frontier. He paid bribes, hired spies, and spent money on fortifications without waiting for the slow, agonizing approval of the Bombay bureaucracy.

He kept records, but they were the records of a soldier, not an accountant. In 1854, the East India Company, looking to cut costs, sent auditors to Aden. They found a deficit of £28,000 in the treasury. There was no evidence Haines had stolen the money for personal gain—he lived modestly and died poor—but he could not produce the receipts to prove where it had gone.

The Company was unforgiving. They recalled him to Bombay in chains. He was put on trial for fraud and embezzlement. Twice, juries of his peers acquitted him, recognizing his service and integrity. But the Governor of Bombay, Lord Elphinstone, used a loophole in civil law to demand repayment of the £28,000.

Death in the Debtor's Prison

Haines, with his captain's salary, could never repay such a sum. He was thrown into a debtor's prison in Bombay. For six years, the conqueror of Aden rotted in a hot, squalid cell. He watched from his barred window as the ships he had facilitated—the steamers carrying the wealth of India—sailed in and out of the harbor.

His health collapsed. His spirit broke. Finally, in 1860, a new governor, Sir George Clerk, visited the prison and was horrified to find the Empire's hero in such a state. He ordered Haines' immediate release.

Haines stumbled out of prison, a broken old man. He boarded a ship bound for England, hoping to see the white cliffs one last time. He never made it. He died one week later, on June 16, 1860, while the ship was still in Bombay harbor.

The Legacy

Haines died a "criminal," but history vindicated him. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened. Aden instantly became one of the most important ports in the world, the "Gibraltar of the East". It served as the strategic anchor for British power in the Middle East until 1967. The telegraph cables that linked London to Bombay ran through Aden. The coal that fueled the Royal Navy was stacked on its wharves. Haines' vision had reshaped the world, even if the world had crushed him.

Part VII: Strategic Analysis – Data and Logistics

To fully grasp the magnitude of the operation and the strategic value of Aden, we must look at the data. The following tables illustrate the military disparity and the logistical triumph of the Aden acquisition.

Table 1: Comparative Strength - Battle of Aden (Jan 19, 1839)

Feature | British Expeditionary Force | Arab Garrison (Sultanate of Lahej) |

Commanders | Capt. Henry Smith (Naval), Maj. Baillie (Land) | Sultan Muhsin bin Fadl, Nephew Ahmed |

Troop Strength | ~700 Infantry & Marines, 4 Warships | ~1,000 Irregulars & Mercenaries |

Naval Power | 69 heavy naval guns (32-pounders) | None (Land-based batteries only) |

Artillery | 12-pounder field guns, Howitzers | 33 Antiquated Bronze Cannons |

Weaponry | Flintlock Muskets (Brown Bess), Bayonets | Matchlocks, Jezails, Jambiya Daggers |

Casualties | 15-17 Wounded (0 Killed in Action) | ~150 Killed/Wounded, 139 Prisoners |

Outcome | Total Victory | Total Defeat, Fortress Captured |

Table 2: The Logic of Coal – Why Aden?

Factor | Socotra (Rejected) | Aden (Selected) |

Harbor | Exposed to Monsoons (Jun-Sep) | Protected Natural Harbor (Crater) |

Defensibility | Hard to defend, large coastline | Peninsula, narrow isthmus (chokepoint) |

Water | Available but inland | Scare (Cisterns required repair) |

Political Status | Sultan of Mahra refused sale | Sultan of Lahej hostile but conquerable |

Strategic Position | Flank of the route | Direct line Suez-Bombay |

Future Utility | Limited | High (Telegraph hub, Free Port) |

Table 3: The Growth of Aden Under British Rule

Year | Population | Strategic Status | Key Event |

1839 | ~600 | Fishing Village | Capture by Captain Haines |

1842 | ~15,000 | Coaling Station | Fortifications strengthened |

1850 | ~20,000 | Free Port | Customs duties abolished |

1869 | Rapid Growth | Global Hub | Opening of Suez Canal |

1900s | ~40,000+ | "Gibraltar of the East" | Major Telegraph/Naval Base |

Part VIII: Strategic Application – The "Aden Protocol" for the Individual

The history of January 19, 1839, is not merely a record of imperial expansion; it is a profound case study in strategic seizure. It demonstrates how to identify a bottleneck, manufacture a pretext for action, and apply overwhelming force to secure a resource that changes your trajectory.

In the modern context, we are not conquering peninsulas. But we are all captains of our own vessels, trying to navigate vast distances (careers, life goals) with finite fuel (energy, time, money). Without an "Aden"—a secure, fortified position that refuels us—we drift. Here is the Aden Protocol: a motivational and strategic plan derived directly from the historical facts of the expedition.

Here is the Aden Protocol: a motivational and strategic plan derived directly from the historical facts of the expedition.

Identify Your "Coaling Station" (The Logistical Imperative)

Historical Insight: The British realized they could not reach India with continuous steam without a depot. They didn't try to "try harder" to sail without coal; they changed the map to get the coal. Personal Application:

The Bottleneck Analysis: What is the one resource stopping you from reaching your "Bombay" (Major Goal)? Is it physical energy (sleep/fitness)? Is it capital (savings)? Is it specialized knowledge?

Stop Drifting: Most people try to sail the whole way on willpower. Willpower is like wind; it is fickle. You need coal (systems).

The Target: Identify the one habit or resource that, if secured, makes the rest of the journey inevitable. Example: "My Aden is 8 hours of sleep. If I secure that, I can steam through any workday."

The Doria DowlutPrinciple (Weaponizing Setbacks)

Historical Insight: The British didn't mourn the wreck of the Doria Dowlut. They used the "insult" as a legal and moral justification to take aggressive action they had planned anyway. Personal Application:

The Casus Belli: Has life "plundered" you recently? A layoff, a breakup, a failure? Do not wallow in victimhood.

Constructive Aggression: Use that setback as your pretext for massive expansion. "Because I was fired (The Insult), I am now justified in launching the business I was scared to start."

Reframing: The wreck isn't the end; it's the trigger for the invasion of your new life.

The "Sira" Protocol (Overwhelming Force)

Historical Insight: Captain Smith didn't send a canoe to Sira Island. He sent 28-gun frigates. He bombarded the walls for two hours before sending in the Marines. He ensured the math of victory was in his favor before a single boot hit the sand. Personal Application:

No Half Measures: When you decide to capture your "Aden" (e.g., getting fit), don't "try a little." Bring the heavy artillery. Hire the coach, buy the food, block the calendar, remove the junk from the house.

Bombard the Resistance: Soften up the target. Remove obstacles before you attack. If you want to write a book, "bombard" your schedule by cancelling Netflix subscriptions and social obligations before you start writing.

The Landing: When you move, move with bayonets fixed. Total commitment.

The "Free Port" Strategy (Attracting Value)

Historical Insight: Haines didn't just build a fort; he made Aden a tax-free port. This attracted merchants from all over the Indian Ocean, bypassing the competitors. Personal Application:

Become a Hub: How can you make yourself a "Free Port" for ideas and people? Be generous with your network. Remove "taxes" (friction/drama) from interacting with you.

Attract, Don't Chase: Create an environment (skills, attitude) where opportunity wants to dock.

The Haines Warning (Avoid the Debtor's Prison)

Historical Insight: Haines won the war but lost the peace because he neglected his administrative "rear guard." He ignored the accounting while building the empire. Personal Application:

The Audit: You can achieve massive success and still end up "bankrupt" in health or relationships.

Balance the Ledger: As you conquer, keep your receipts. Don't sacrifice your family (the treasury) for the sake of the career (the fort).

The End Game: Ensure that when you win, you are free to enjoy it, not imprisoned by the debts (health/stress) you incurred to get there.

Conclusion

On January 19, 1839, the smoke cleared over Sira Island to reveal the Union Jack snapping in the wind. The "Eye of Yemen" had blinked, and in that blink, the world changed. The Age of Steam had found its anchor.

The capture of Aden was an act of supreme imperial will, driven by the cold logic of logistics and executed with the fire of modern technology. It teaches us that destiny is not something you wait for; it is something you survey, you plan for, and ultimately, when the wind is right and the fleet is ready, you seize with both hands.

You are the Captain. The Volage is ready. Your Aden awaits.

Prepare to land.

This geography is destiny. For millennia, long before the British East India Company turned its covetous gaze toward the Red Sea, Aden served as the "Eye of Yemen." It stands at the confluence of the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea. It guards the Bab-el-Mandeb—the "Gate of Tears"—the narrow strait that separates Africa from Arabia. Whoever controls Aden controls the flow of trade between the Mediterranean and the East. The Romans knew this, calling it Eudaemon Arabia (Happy Arabia). The Ottomans knew this, seizing it in 1538 to check the Portuguese expansion in the Indian Ocean. And by the 1830s, the British Empire, fueled by the fires of the Industrial Revolution, knew it with a desperate, burning certainty. The landscape of Aden in the early 19th century was a study in contrasts. To the mariner, the dramatic skyline of Jebel Shamsan—the highest peak of the crater—offered a navigational beacon visible for miles. The natural harbor, known as the Back Bay (later Aden Harbour) and Front Bay, provided shelter even during the fiercest monsoons. Yet, to the inhabitant, it was a waterless, sun-scorched rock. The ancient cisterns, carved into the rock to catch the rare torrential rains, had fallen into disrepair. The settlement, once a thriving emporium of thousands, had dwindled under the rule of the Abdali Sultans of Lahej to a squalid fishing village of barely 600 souls—Arabs, Somalis, Jews, and Banyans living in huts of reed matting amidst the ruins of stone palaces. It was here, on this desolate cinder of a peninsula, that the Victorian age would make its first definitive, violent mark on the map of the Middle East. The capture of Aden was not an isolated skirmish; it was the tectonic collision of two eras. It was the moment where the Age of Sail, represented by the dhows and reliance on trade winds, was brutally superseded by the Age of Steam. The British did not take Aden for gold, spices, or territory in the traditional sense. They took it because a new beast had been born in the shipyards of Britain—the steamship—and that beast had a voracious, insatiable appetite for coal. The Steam Imperative and the tyranny of Logistics The backstory of January 19, 1839, is written in soot and steam. By the 1830s, the communication lines between London and Bombay were stretched to the breaking point. The traditional route via the Cape of Good Hope was a grueling odyssey that could take four to six months. A letter sent from Calcutta might not receive a reply for two years. For an empire that relied on information—market prices, troop movements, political intelligence—this lag was intolerable. The solution lay in the "Overland Route" through Egypt and the Red Sea. A steamship could travel from Bombay to Suez, passengers could cross the desert to Alexandria, and another ship could carry them to Europe. This route promised to cut the journey in half. But early steamships were inefficient. They were paddle-wheelers that guzzled coal at a prodigious rate. A steamer like the Hugh Lindsay, which made the pioneering voyage in 1830, could not carry enough fuel to cross the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea in one leg. They needed "gas stations" of the sea—coaling depots where they could restock. This logistical reality transformed the barren rocks of the Arabian coast into the most valuable real estate in the empire. The East India Company (EIC) initially looked to the island of Socotra. It sat at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden. Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines, a brilliant and ambitious surveyor of the Indian Navy, was sent to map it and acquire it. But Socotra proved a failure. It lacked a secure harbor, was ravaged by fevers, and was battered by monsoons that made coaling dangerous. Haines, with the surveyor's eye for topography and the strategist's eye for war, turned his attention to Aden. He saw what the Board of Directors in Bombay could not: Aden was the perfect fortress. Its harbor was defended by nature. Its position was unassailable. If the British did not take it, others would. The Egyptians, under the expansionist Muhammad Ali Pasha, were marching down the Arabian coast. The Americans and French were sniffing around the Red Sea. The race for the "Coal Hole of the East" was on, and Haines was determined to win it. Part II: The Pretext – The Tragedy of the Doria Dowlut A Cargo of Riches and Pilgrims History often turns on the fate of a single ship. In the case of Aden, that ship was the Doria Dowlut. She was a barque of 225 tons, flying the British flag—a crucial legal detail—and owned by the Begum Ahmed Nissa, the mother of the Nawab of Madras. In early 1837, she was sailing from Calcutta to Jeddah, carrying a cargo that evokes the richness of the Indian Ocean trade: Bengali textiles, Kinkaub (gold-embroidered cloth), Chinese satin, rose perfume, ginger, pepper, and iron. But the Doria Dowlut carried something more precious than spices: pilgrims. The ship was laden with Muslim devotees bound for the Hajj in Mecca. Among them were wealthy merchants and their families, carrying their life savings in gold and jewelry. On the dark morning of February 20, 1837, the Doria Dowlut drifted into the waters off Aden. Whether by treacherous currents or, as Captain Haines would later allege, the treachery of a pilot paid to run her aground, the vessel struck the seabed about four miles northeast of the peninsula. The Plunder and the Insult What happened next shifted the incident from a maritime tragedy to a casus belli. The ship did not break apart immediately. As she listed in the surf, she was spotted by the Abdali tribesmen of Aden. In the ethos of the coast, a wreck was a gift from God. But the Doria Dowlut was under British protection, and the response of the locals went far beyond salvage. The depositions taken by British agents paint a harrowing picture of the chaotic hours that followed. Skiffs launched from the shore, not to rescue the drowning pilgrims, but to strip them. The cargo was hauled away—rice, sugar, and the precious textiles disappeared into the storehouses of the Sultan of Lahej. The human cost was far uglier. Survivors reported that the Bedouin plunderers stripped women naked to search for gold hidden in their clothes. The ship’s captain, Nakhooda Syed Nouradeen, testified that he was held underwater by his beard and tortured until he revealed the location of the ship’s specie.

When the battered survivors finally reached the shore, they were not offered hospitality but were further exploited. Eventually, they made their way to Mocha, where they encountered Captain Stafford Haines. Haines, ever the diligent officer, took their depositions. He saw the genuine trauma in their accounts—the robbery, the rape, the bribery, and the manslaughter. But Haines also saw something else. He saw the "Insult to the Flag." In the diplomatic language of the 19th century, the mistreatment of a ship flying British colors was an attack on the sovereignty of the Crown itself. It provided the moral and legal leverage the East India Company needed. The Doria Dowlut affair gave the British a justification that went beyond mere coal. They could now cloak their strategic ambition in the righteous robes of justice and protection. The Diplomatic Dance of Deception Haines was dispatched to Aden in the sloop Coote to demand reparations. He carried a bill for 12,000 Maria Theresa Thalers (the currency of the region) for the stolen cargo. But his secret instructions were clear: if the Sultan could not pay—and everyone knew he could not—Haines was authorized to accept the cession of Aden to the British Crown in lieu of payment. For nearly a year, a tense game of cat and mouse played out between Captain Haines and Sultan Muhsin bin Fadl of Lahej. Sultan Muhsin was an aging, wily ruler, struggling to maintain his authority over unruly tribes and greedy sons. He knew the British were dangerous, but he also feared losing his sovereignty. The negotiations were a masterclass in frustration. The Sultan would agree to sell the peninsula one day, then renege the next. He claimed his seal had been stolen. He claimed his sons refused to agree. At one point, his son Hamed attempted to kidnap Haines during a meeting to force him to drop the demands. Haines, displaying the icy nerve that would characterize his career, escaped the trap. The situation deteriorated. The Sultan sent letters of friendship while his soldiers reinforced the fortifications on Sira Island. On December 13, 1838, the pretense of diplomacy shattered. Arab soldiers on the shore fired muskets at the Coote’s boats. Haines, seizing the moment, declared this an act of war. He instituted a blockade and sent word to Bombay: the time for talking was over. The "Eye of Yemen" would have to be taken by fire. Part III: The Armada Assembles – Order of Battle The Naval Hammer The Government of Bombay, led by Governor Robert Grant, authorized the expedition. This was not to be a punitive raid; it was a conquest. The force assembled was overwhelming for the time and place, a mix of the Royal Navy’s global reach and the Indian Navy’s local expertise. The Naval Squadron:

For nearly two hours, the bay was choked with sulfurous smoke. The British gunnery was relentless and disciplined. They systematically dismantled the defenses. The great tower on Sira Island, which had stood for centuries, crumbled under the weight of the barrage. The Arab return fire, initially spirited, began to slacken as their guns were dismounted and their gunners killed or driven into the rocks. Captain Haines, watching from the Coote, noted the devastation. The "modern" war machine of Europe was dismantling the medieval defenses of Arabia with terrifying efficiency. The Storming of Sira By 11:00 AM, the enemy fire had been silenced. The signal to land was hoisted. The boats were lowered from the Lowjee Family and the Ernaad. Major Baillie led the 24th Bombay Native Infantry and the Europeans into the pinnaces. They rowed hard for the shore, oars dipping in unison. As the keels crunched onto the sand, the troops vaulted over the gunwales, bayonets fixed. A scattered, desperate musketry erupted from the ruins, but the British charge was unstoppable. Captain Smith landed with a party of seamen and Marines from the Volage to storm the Sira fortress directly. They fought their way up the causeway, engaging in vicious hand-to-hand combat with the surviving defenders who refused to surrender. The disciplined bayonet drills of the Marines overcame the desperate courage of the tribesmen. They reached the summit of Sira. The Sultan’s red flag was still flying. A British sailor shinned up the pole, tore it down, and hoisted the Union Jack. It was the first time the British flag would fly over a colony in Queen Victoria’s reign. The Capture of the Town With the fortress taken, the troops advanced into Aden town. They found it largely deserted; the women and children had been evacuated to the interior. The Sultan’s palace was stormed and secured. By the afternoon, the shooting had stopped. The casualty count told the story of technological asymmetry. The British had lost no men killed in action during the assault, though 15 to 17 were wounded (some later died of wounds). The Arab defenders had suffered heavily: over 150 killed and wounded. The British captured 139 prisoners and all 33 guns. Haines stood amidst the ruins of the town. The "Eye of Yemen" was theirs. The strategic pivot of the Indian Ocean had been seized for the price of a few dozen casualties and a morning’s worth of gunpowder. Part V: The Anchor of Empire – Building the Coal Hole The Transformation The conquest was only the beginning. Captain Haines was appointed the first Political Agent of Aden, a post he would hold for fifteen years. He found a ruin; he built a metropolis. Haines understood that for Aden to succeed, it had to be more than a fortress; it had to be a market. He declared Aden a "Free Port" in 1850, abolishing the customs duties that choked trade in other Red Sea ports like Mocha. He invited merchants from India—Parsees, Banyans, and Borahs—to settle, offering them land and protection. He encouraged the Jewish community of Aden to rebuild their lives free from the persecution of the Sultans. The results were miraculous. The population exploded from 600 in 1839 to over 20,000 by the mid-1850s. The harbor was dredged and fortified. Huge coal depots were constructed, fed by colliers from Wales. Aden became the lifeblood of the Empire. Every P&O steamer carrying mail, officials, or troops to India stopped at Aden. It became a "Little London" on the Arabian coast, a place of clubs, churches, and commerce.

The Fortification of the Hinterland But the Sultan of Lahej did not give up. Stung by the loss of his revenue, he launched repeated attacks on the settlement in 1840 and 1846, trying to drive the "infidels" into the sea. Haines responded by building a massive defensive wall across the isthmus—the "Turkish Wall"—and cultivating a network of spies among the tribes. He used a "divide and rule" strategy, paying stipends to friendly sheikhs while punishing hostiles with artillery. Part VI: The Tragedy of Stafford Haines – The Martyr of Bureaucracy The Visionary's Fall There is a bitter irony at the heart of the Aden story. Stafford Haines, the man who gave Britain the key to the East, was destroyed by the very empire he served. Haines was a "man on the spot"—a proactive, independent operator who did what was necessary to survive on a hostile frontier. He paid bribes, hired spies, and spent money on fortifications without waiting for the slow, agonizing approval of the Bombay bureaucracy. He kept records, but they were the records of a soldier, not an accountant. In 1854, the East India Company, looking to cut costs, sent auditors to Aden. They found a deficit of £28,000 in the treasury. There was no evidence Haines had stolen the money for personal gain—he lived modestly and died poor—but he could not produce the receipts to prove where it had gone. The Company was unforgiving. They recalled him to Bombay in chains. He was put on trial for fraud and embezzlement. Twice, juries of his peers acquitted him, recognizing his service and integrity. But the Governor of Bombay, Lord Elphinstone, used a loophole in civil law to demand repayment of the £28,000. Death in the Debtor's Prison Haines, with his captain's salary, could never repay such a sum. He was thrown into a debtor's prison in Bombay. For six years, the conqueror of Aden rotted in a hot, squalid cell. He watched from his barred window as the ships he had facilitated—the steamers carrying the wealth of India—sailed in and out of the harbor. His health collapsed. His spirit broke. Finally, in 1860, a new governor, Sir George Clerk, visited the prison and was horrified to find the Empire's hero in such a state. He ordered Haines' immediate release. Haines stumbled out of prison, a broken old man. He boarded a ship bound for England, hoping to see the white cliffs one last time. He never made it. He died one week later, on June 16, 1860, while the ship was still in Bombay harbor. The Legacy Haines died a "criminal," but history vindicated him. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened. Aden instantly became one of the most important ports in the world, the "Gibraltar of the East". It served as the strategic anchor for British power in the Middle East until 1967. The telegraph cables that linked London to Bombay ran through Aden. The coal that fueled the Royal Navy was stacked on its wharves. Haines' vision had reshaped the world, even if the world had crushed him. Part VII: Strategic Analysis – Data and Logistics To fully grasp the magnitude of the operation and the strategic value of Aden, we must look at the data. The following tables illustrate the military disparity and the logistical triumph of the Aden acquisition. Table 1: Comparative Strength - Battle of Aden (Jan 19, 1839)

Here is the Aden Protocol: a motivational and strategic plan derived directly from the historical facts of the expedition.