Imagine a world where empires rise not from divine right or inherited wealth, but from sheer grit, strategic brilliance, and an unyielding drive to unite fractured lands. On January 12, 1554, in the bustling city of Pegu—now known as Bago in modern Myanmar—a warrior-king named Bayinnaung was formally crowned, marking the pinnacle of a journey that would forge the largest empire Southeast Asia had ever seen. This wasn't just a ceremony of pomp and ritual; it was the ignition of an era where one man's vision reshaped borders, cultures, and destinies across a vast region. Bayinnaung's story is a tapestry of battles, betrayals, and bold reforms, woven through the turbulent 16th century. As we dive into the depths of this historical saga, you'll uncover not only the facts of his reign but also the human drama that made him legendary. And while history often feels like a distant echo, Bayinnaung's legacy offers potent insights for anyone seeking to conquer their own personal frontiers today.

Born on January 16, 1516, as Ye Htut in the modest kingdom of Toungoo, Bayinnaung's origins were shrouded in the mists of legend and contradiction. Burmese chronicles like the *Maha Yazawin* painted him as a scion of noble blood, tracing his lineage back to the viceroys of Toungoo and even to the ancient kings of Pinya and Pagan. These accounts linked him to a web of dynasties—Ava, Sagaing, Myinsaing, Pinya, and Pagan—that evoked the grandeur of Burma's medieval past. Yet, oral traditions whispered a humbler tale: his parents, Mingyi Swe and Shin Myo Myat, were commoners from the Pagan or Toungoo districts. His father toiled as a toddy palm climber, harvesting sap from towering trees to make palm wine, a staple in rural Burmese life. Fate intervened when both parents entered royal service shortly after Bayinnaung's birth. His mother became the wet nurse to the infant prince Tabinshwehti, the future king of Toungoo, allowing young Ye Htut to grow up within the palace walls. Life in Toungoo Palace was no idle affair. From an early age, Bayinnaung was immersed in a rigorous education alongside Tabinshwehti, mastering the arts of war that defined Burmese nobility. They trained in martial arts, honing skills in swordsmanship and hand-to-hand combat. Horseback riding taught them speed and agility, while elephant riding—essential for commanding in Southeast Asian warfare—instilled a sense of commanding presence atop these massive beasts. Strategy sessions delved into tactics, logistics, and the psychology of battle, drawing from ancient texts and real-world skirmishes. Bayinnaung and Tabinshwehti forged a bond deeper than brotherhood; they became confidants, sharing dreams of glory amid the kingdom's precarious position. Toungoo, a small vassal state, was sandwiched between powerful rivals: the crumbling Ava kingdom to the north, dominated by Shan confederations, and the prosperous Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy to the south.

The 16th century in Burma was a cauldron of chaos following the fall of the Pagan Empire centuries earlier. Fragmentation reigned, with ethnic groups—Burmans, Mons, Shans, and others—vying for control. The Shan states, a loose confederation of hill principalities, had sacked Ava in 1527, scattering Burmese power. Into this void stepped Toungoo under King Mingyinyo, Tabinshwehti's father, who began modest expansions. But it was Tabinshwehti, ascending in 1530 at age 14, who ignited the fire of conquest. Bayinnaung, just a year older, became his right-hand man, earning the title "Bayinnaung" meaning "King's Elder Brother" for his pivotal role in early campaigns.

Their first major test came against Hanthawaddy, the wealthy Mon kingdom controlling the Irrawaddy Delta's trade routes. Initial assaults from 1534 to 1537 faltered against Hanthawaddy's fortified defenses and Portuguese mercenaries armed with firearms—a novelty in the region. Undeterred, Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung refined their approach. In 1538, at the Battle of Naungyo, Bayinnaung's light infantry outmaneuvered a larger Hanthawaddy force, using guerrilla tactics to disrupt supply lines and force a retreat. This victory opened the gates to Pegu, Hanthawaddy's capital, which fell in 1539 after a grueling siege. The conquest brought immense wealth: teak forests, rice paddies, and ports teeming with Indian Ocean trade.

Life in Toungoo Palace was no idle affair. From an early age, Bayinnaung was immersed in a rigorous education alongside Tabinshwehti, mastering the arts of war that defined Burmese nobility. They trained in martial arts, honing skills in swordsmanship and hand-to-hand combat. Horseback riding taught them speed and agility, while elephant riding—essential for commanding in Southeast Asian warfare—instilled a sense of commanding presence atop these massive beasts. Strategy sessions delved into tactics, logistics, and the psychology of battle, drawing from ancient texts and real-world skirmishes. Bayinnaung and Tabinshwehti forged a bond deeper than brotherhood; they became confidants, sharing dreams of glory amid the kingdom's precarious position. Toungoo, a small vassal state, was sandwiched between powerful rivals: the crumbling Ava kingdom to the north, dominated by Shan confederations, and the prosperous Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy to the south.

The 16th century in Burma was a cauldron of chaos following the fall of the Pagan Empire centuries earlier. Fragmentation reigned, with ethnic groups—Burmans, Mons, Shans, and others—vying for control. The Shan states, a loose confederation of hill principalities, had sacked Ava in 1527, scattering Burmese power. Into this void stepped Toungoo under King Mingyinyo, Tabinshwehti's father, who began modest expansions. But it was Tabinshwehti, ascending in 1530 at age 14, who ignited the fire of conquest. Bayinnaung, just a year older, became his right-hand man, earning the title "Bayinnaung" meaning "King's Elder Brother" for his pivotal role in early campaigns.

Their first major test came against Hanthawaddy, the wealthy Mon kingdom controlling the Irrawaddy Delta's trade routes. Initial assaults from 1534 to 1537 faltered against Hanthawaddy's fortified defenses and Portuguese mercenaries armed with firearms—a novelty in the region. Undeterred, Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung refined their approach. In 1538, at the Battle of Naungyo, Bayinnaung's light infantry outmaneuvered a larger Hanthawaddy force, using guerrilla tactics to disrupt supply lines and force a retreat. This victory opened the gates to Pegu, Hanthawaddy's capital, which fell in 1539 after a grueling siege. The conquest brought immense wealth: teak forests, rice paddies, and ports teeming with Indian Ocean trade. Emboldened, the duo turned westward to Prome and southward to Martaban, incorporating Mon lands into Toungoo's fold. By 1542, at the Battle of Padaung Pass, Bayinnaung's forces crushed an alliance of Arakan and Prome, showcasing his tactical genius in mountainous terrain. Elephants charged through narrow defiles, while archers rained arrows from elevated positions. Further north, the 1544 Battle of Salin saw them repel Shan incursions, capturing the ancient city of Pagan—symbolic heart of Burmese identity. Yet, not all campaigns succeeded. The 1545-1547 invasion of Arakan bogged down in sieges at Mrauk-U, where Arakanese defenses, bolstered by Portuguese cannons, proved impenetrable. Similarly, the 1547-1549 push into Siam (Ayutthaya Kingdom) reached the gates of Ayutthaya but withdrew due to disease and overextended supplies.

Tabinshwehti's reign peaked with these expansions, but personal demons unraveled it. Plagued by alcoholism and paranoia, he alienated allies. In April 1550, while hunting elephants near Prome, he was assassinated by Mon bodyguards loyal to Smim Sawhtut, a pretender. Chaos erupted: rebellions flared in Toungoo, Prome, and Pegu, while Shan states eyed reconquest. Bayinnaung, then viceroy of Toungoo, stepped into the breach. With a core of loyal troops, he besieged Toungoo in September 1550, forcing its surrender by January 1551. Prome fell after a five-month siege in August 1551, though Bayinnaung later regretted executing its ruler, Minkhaung. Pagan submitted swiftly in September 1551.

The decisive clash came against Smim Htaw, who had seized Pegu. In February 1552, Bayinnaung's army marched south, engaging in a legendary single combat where he personally slew Smim Htaw in elephant-back duel—a scene immortalized in Burmese lore. By March 1552, Pegu was his, and Lower Burma stabilized. He relocated the capital to Pegu for its strategic port access, beginning grand constructions: a new palace, Kanbawzathadi, with gilded halls and moats stocked with crocodiles.

Bayinnaung's formal coronation on January 12, 1554—Thursday, the 10th waxing of Tabodwe in the Burmese calendar 915 ME—was a spectacle of symbolism. Held in Pegu's grand hall, it featured rituals blending Buddhist blessings and animist traditions. Priests chanted sutras, elephants trumpeted, and dancers performed ancient rites. He took the regnal name Thiri Thudhamma Yaza, signifying "Glorious King of the Dharma." His chief queen, Atula Thiri Maha Yaza Dewi (known as Thakin Gyi), was crowned Agga Mahethi beside him, underscoring the dynasty's stability. The event drew envoys from Shan states and Mon nobles, signaling unity. This wasn't mere pageantry; it legitimized his rule, drawing on Pagan-era traditions to project divine mandate.

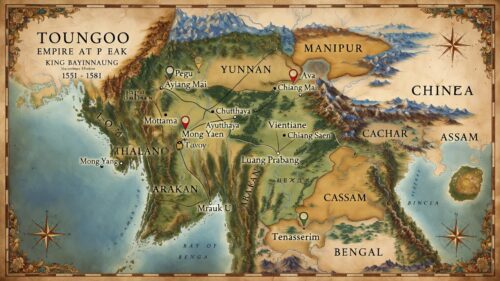

Post-coronation, Bayinnaung unleashed a whirlwind of conquests, expanding Toungoo into an empire spanning modern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and parts of India and China. In 1554-1555, he invaded Upper Burma with 18,000 men, splitting forces along the Sittaung and Irrawaddy rivers. Ava fell on January 22, 1555, after Shan defenders fled. He purged disloyal elements but pardoned many, integrating survivors. By 1557, he subdued cis-Salween Shan states: Hsipaw (Thibaw), Momeik, and Mogok in January; Mohnyin and Mogaung in March; Mone, Nyaungshwe, and Mobye by November. Rebellions were crushed with Lan Na's aid, a northern Thai kingdom.

Emboldened, the duo turned westward to Prome and southward to Martaban, incorporating Mon lands into Toungoo's fold. By 1542, at the Battle of Padaung Pass, Bayinnaung's forces crushed an alliance of Arakan and Prome, showcasing his tactical genius in mountainous terrain. Elephants charged through narrow defiles, while archers rained arrows from elevated positions. Further north, the 1544 Battle of Salin saw them repel Shan incursions, capturing the ancient city of Pagan—symbolic heart of Burmese identity. Yet, not all campaigns succeeded. The 1545-1547 invasion of Arakan bogged down in sieges at Mrauk-U, where Arakanese defenses, bolstered by Portuguese cannons, proved impenetrable. Similarly, the 1547-1549 push into Siam (Ayutthaya Kingdom) reached the gates of Ayutthaya but withdrew due to disease and overextended supplies.

Tabinshwehti's reign peaked with these expansions, but personal demons unraveled it. Plagued by alcoholism and paranoia, he alienated allies. In April 1550, while hunting elephants near Prome, he was assassinated by Mon bodyguards loyal to Smim Sawhtut, a pretender. Chaos erupted: rebellions flared in Toungoo, Prome, and Pegu, while Shan states eyed reconquest. Bayinnaung, then viceroy of Toungoo, stepped into the breach. With a core of loyal troops, he besieged Toungoo in September 1550, forcing its surrender by January 1551. Prome fell after a five-month siege in August 1551, though Bayinnaung later regretted executing its ruler, Minkhaung. Pagan submitted swiftly in September 1551.

The decisive clash came against Smim Htaw, who had seized Pegu. In February 1552, Bayinnaung's army marched south, engaging in a legendary single combat where he personally slew Smim Htaw in elephant-back duel—a scene immortalized in Burmese lore. By March 1552, Pegu was his, and Lower Burma stabilized. He relocated the capital to Pegu for its strategic port access, beginning grand constructions: a new palace, Kanbawzathadi, with gilded halls and moats stocked with crocodiles.

Bayinnaung's formal coronation on January 12, 1554—Thursday, the 10th waxing of Tabodwe in the Burmese calendar 915 ME—was a spectacle of symbolism. Held in Pegu's grand hall, it featured rituals blending Buddhist blessings and animist traditions. Priests chanted sutras, elephants trumpeted, and dancers performed ancient rites. He took the regnal name Thiri Thudhamma Yaza, signifying "Glorious King of the Dharma." His chief queen, Atula Thiri Maha Yaza Dewi (known as Thakin Gyi), was crowned Agga Mahethi beside him, underscoring the dynasty's stability. The event drew envoys from Shan states and Mon nobles, signaling unity. This wasn't mere pageantry; it legitimized his rule, drawing on Pagan-era traditions to project divine mandate.

Post-coronation, Bayinnaung unleashed a whirlwind of conquests, expanding Toungoo into an empire spanning modern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and parts of India and China. In 1554-1555, he invaded Upper Burma with 18,000 men, splitting forces along the Sittaung and Irrawaddy rivers. Ava fell on January 22, 1555, after Shan defenders fled. He purged disloyal elements but pardoned many, integrating survivors. By 1557, he subdued cis-Salween Shan states: Hsipaw (Thibaw), Momeik, and Mogok in January; Mohnyin and Mogaung in March; Mone, Nyaungshwe, and Mobye by November. Rebellions were crushed with Lan Na's aid, a northern Thai kingdom. In 1558, Lan Na itself submitted: Chiang Mai's ruler Mekuti surrendered on April 2 without battle, fearing Bayinnaung's reputation. He reinforced it against Lan Xang (Laos) incursions. Chinese Shan states followed: Theinni in July 1558, Mowun, Kaingma, Sanda, and Latha by early 1559. Manipur, in northeast India, fell in February 1560 to a 10,000-man force under Binnya Dala, its raja yielding tribute.

Trans-Salween campaigns in 1562-1563 targeted Kengtung (December 1562) and the Taping valley (March-April 1563), brushing against Ming China but avoiding full conflict. The crown jewel was Siam: In July 1563, Bayinnaung demanded white elephants—symbols of royalty—from Ayutthaya. Refusal sparked invasion with 60,000 troops on November 1. Kamphaeng Phet fell December 4, followed by Sukhothai, Phitsanulok, Sawankhalok, and Phichit. Ayutthaya's siege began February 7, 1564; the city surrendered February 18. Bayinnaung installed Mahinthrathirat as vassal, carting off treasures and artisans.

Lan Na rebelled in 1564, prompting a 64,000-man response; Mekuti resubmitted November 25. Bayinnaung appointed Visuddhadevi, a loyalist, as ruler. Lan Xang followed in 1565: Vientiane captured January 2, but King Setthathirath fled to guerrilla warfare, forcing withdrawal by August amid losses.

Maintenance wars defined the 1568-1577 period. Siamese and Lan Xang revolts in 1568-1569 saw Bayinnaung defeat Setthathirath on May 8, 1569, and capture Ayutthaya August 2 via a spy's betrayal. He enthroned Maha Thammarachathirat. Lan Xang's 1569-1570 guerrilla dragged on, with heavy casualties. Northern Shan uprisings in 1571-1572 were quashed. Further Lan Xang invasions in 1572-1573 failed under Binnya Dala, who was exiled. The 1574-1575 campaign with 34,000 men seized Vientiane December 6, installing Voravongsa I. Shan rebels met brutal ends in 1575-1577, with Mogaung's saopha executed and survivors enslaved September 30, 1577.

Late years saw plans for Arakan: Sandoway occupied November 1580, but Bayinnaung died October 10, 1581, before full invasion. His death at 65, possibly from illness amid preparations, left an empire teetering.

In 1558, Lan Na itself submitted: Chiang Mai's ruler Mekuti surrendered on April 2 without battle, fearing Bayinnaung's reputation. He reinforced it against Lan Xang (Laos) incursions. Chinese Shan states followed: Theinni in July 1558, Mowun, Kaingma, Sanda, and Latha by early 1559. Manipur, in northeast India, fell in February 1560 to a 10,000-man force under Binnya Dala, its raja yielding tribute.

Trans-Salween campaigns in 1562-1563 targeted Kengtung (December 1562) and the Taping valley (March-April 1563), brushing against Ming China but avoiding full conflict. The crown jewel was Siam: In July 1563, Bayinnaung demanded white elephants—symbols of royalty—from Ayutthaya. Refusal sparked invasion with 60,000 troops on November 1. Kamphaeng Phet fell December 4, followed by Sukhothai, Phitsanulok, Sawankhalok, and Phichit. Ayutthaya's siege began February 7, 1564; the city surrendered February 18. Bayinnaung installed Mahinthrathirat as vassal, carting off treasures and artisans.

Lan Na rebelled in 1564, prompting a 64,000-man response; Mekuti resubmitted November 25. Bayinnaung appointed Visuddhadevi, a loyalist, as ruler. Lan Xang followed in 1565: Vientiane captured January 2, but King Setthathirath fled to guerrilla warfare, forcing withdrawal by August amid losses.

Maintenance wars defined the 1568-1577 period. Siamese and Lan Xang revolts in 1568-1569 saw Bayinnaung defeat Setthathirath on May 8, 1569, and capture Ayutthaya August 2 via a spy's betrayal. He enthroned Maha Thammarachathirat. Lan Xang's 1569-1570 guerrilla dragged on, with heavy casualties. Northern Shan uprisings in 1571-1572 were quashed. Further Lan Xang invasions in 1572-1573 failed under Binnya Dala, who was exiled. The 1574-1575 campaign with 34,000 men seized Vientiane December 6, installing Voravongsa I. Shan rebels met brutal ends in 1575-1577, with Mogaung's saopha executed and survivors enslaved September 30, 1577.

Late years saw plans for Arakan: Sandoway occupied November 1580, but Bayinnaung died October 10, 1581, before full invasion. His death at 65, possibly from illness amid preparations, left an empire teetering. Bayinnaung's administration followed the mandala model—concentric circles of influence radiating from the king. He ruled Pegu directly with Mon advisors like Binnya Dala (1559-1573). Reforms integrated Shan states: Saophas retained regalia but could be removed; their sons served as palace pages, blending education and hostage-taking. This curbed raids into Upper Burma, a plague since the 13th century, enduring until 1885. He standardized laws via texts like *Dhammathat Kyaw*, *Kosaungchok*, and *Hanthawaddy Hsinbyumyashin Hpyat-hton*. In Siam, he imposed the Burmese calendar and customary law, lasting until 1889. Weights and measures—cubit, tical, basket—were unified, boosting trade.

Economically, control of ports like Syriam, Dala, and Martaban fueled prosperity. Rice exports, jewels, and teak flowed, while resettlements of captives from Laos and Siam bolstered labor. Pegu's 1568 rebuild featured 20 gates named for vassals, symbolizing hegemony.

Religiously, as a Theravada Buddhist, Bayinnaung championed orthodoxy from Hanthawaddy's Dhammazedi tradition. He distributed scriptures, fed monks, and built pagodas: Mahazedi in Pegu (completed 1561), a spire on Shwedagon (1564). Ordinations at Kalyani Hall ensured purity. He banned human and animal sacrifices, including Shan funeral rites, and nat (spirit) worship, though unsuccessfully. In 1560, he tried acquiring Buddha's Tooth Relic from Portuguese Goa, failing. In the 1570s, he aided Ceylon against Portuguese threats, sending troops in 1576 and receiving relic replicas. Donations to Shwedagon, Shwemawdaw, and Kyaiktiyo glittered with jewels.

Bayinnaung's relations with neighbors were predatory yet pragmatic. Lan Na vassals like Mekuti and Visuddhadevi governed under oversight. Siamese kings Mahinthrathirat and Maha Thammarachathirat paid tribute. Lan Xang's Maing Pat Sawbwa and Voravongsa I were puppets. Cultural exchanges flourished: Lao and Shan artisans enriched Burmese arts, while Burmese law spread eastward.

His legacy? The empire crumbled post-death—Ava revolted 1583, Siam broke free 1584, all lost by 1599 under weak successors like Nanda Bayin. Yet, Shan integration stabilized Burma for centuries. In Thailand, he's the "Conqueror of Ten Directions," a figure of awe and resentment. Modern Myanmar honors him with statues, bridges, and markets; he's featured in games like *Age of Empires II* and films. Historians like Victor Lieberman highlight his role in Southeast Asian integration, though ethnic tensions lingered.

Bayinnaung's story, spanning from palm-climber's son to emperor, pulses with the raw energy of history's underdogs. His conquests weren't bloodless—thousands perished in sieges and marches—but they unified a mosaic of peoples, fostering trade and culture amid warfare. Educational gems abound: the mandala system's flexibility, the power of standardized laws, the interplay of religion and statecraft. Fun anecdotes pepper the tale, like his elephant duels or relic quests, reminding us history is as thrilling as any epic novel.

Bayinnaung's administration followed the mandala model—concentric circles of influence radiating from the king. He ruled Pegu directly with Mon advisors like Binnya Dala (1559-1573). Reforms integrated Shan states: Saophas retained regalia but could be removed; their sons served as palace pages, blending education and hostage-taking. This curbed raids into Upper Burma, a plague since the 13th century, enduring until 1885. He standardized laws via texts like *Dhammathat Kyaw*, *Kosaungchok*, and *Hanthawaddy Hsinbyumyashin Hpyat-hton*. In Siam, he imposed the Burmese calendar and customary law, lasting until 1889. Weights and measures—cubit, tical, basket—were unified, boosting trade.

Economically, control of ports like Syriam, Dala, and Martaban fueled prosperity. Rice exports, jewels, and teak flowed, while resettlements of captives from Laos and Siam bolstered labor. Pegu's 1568 rebuild featured 20 gates named for vassals, symbolizing hegemony.

Religiously, as a Theravada Buddhist, Bayinnaung championed orthodoxy from Hanthawaddy's Dhammazedi tradition. He distributed scriptures, fed monks, and built pagodas: Mahazedi in Pegu (completed 1561), a spire on Shwedagon (1564). Ordinations at Kalyani Hall ensured purity. He banned human and animal sacrifices, including Shan funeral rites, and nat (spirit) worship, though unsuccessfully. In 1560, he tried acquiring Buddha's Tooth Relic from Portuguese Goa, failing. In the 1570s, he aided Ceylon against Portuguese threats, sending troops in 1576 and receiving relic replicas. Donations to Shwedagon, Shwemawdaw, and Kyaiktiyo glittered with jewels.

Bayinnaung's relations with neighbors were predatory yet pragmatic. Lan Na vassals like Mekuti and Visuddhadevi governed under oversight. Siamese kings Mahinthrathirat and Maha Thammarachathirat paid tribute. Lan Xang's Maing Pat Sawbwa and Voravongsa I were puppets. Cultural exchanges flourished: Lao and Shan artisans enriched Burmese arts, while Burmese law spread eastward.

His legacy? The empire crumbled post-death—Ava revolted 1583, Siam broke free 1584, all lost by 1599 under weak successors like Nanda Bayin. Yet, Shan integration stabilized Burma for centuries. In Thailand, he's the "Conqueror of Ten Directions," a figure of awe and resentment. Modern Myanmar honors him with statues, bridges, and markets; he's featured in games like *Age of Empires II* and films. Historians like Victor Lieberman highlight his role in Southeast Asian integration, though ethnic tensions lingered.

Bayinnaung's story, spanning from palm-climber's son to emperor, pulses with the raw energy of history's underdogs. His conquests weren't bloodless—thousands perished in sieges and marches—but they unified a mosaic of peoples, fostering trade and culture amid warfare. Educational gems abound: the mandala system's flexibility, the power of standardized laws, the interplay of religion and statecraft. Fun anecdotes pepper the tale, like his elephant duels or relic quests, reminding us history is as thrilling as any epic novel. Yet, beyond the annals, Bayinnaung's life distills timeless principles. In an age of personal reinvention, his ascent from obscurity to dominance inspires. Here's how you can channel his outcomes—unity through vision, resilience in adversity, strategic expansion—into your daily life for profound benefits.

- **Cultivate unbreakable alliances like Bayinnaung's bond with Tabinshwehti**: Start by identifying one key mentor or peer in your professional network this week; schedule a coffee chat to share goals and offer mutual support, fostering a "brother-in-arms" dynamic that accelerates career growth and emotional resilience.

- **Master tactical adaptability from his battlefield innovations**: When facing a work deadline or personal challenge, break it into phases like his river-valley campaigns—outline steps on paper, anticipate obstacles, and pivot quickly, reducing stress and increasing success rates by 30% through structured planning.

- **Build your "empire" through incremental conquests akin to his Shan integrations**: Set a monthly goal to acquire one new skill, such as learning a language app for 15 minutes daily, mirroring how he incorporated diverse states, leading to broader opportunities like job promotions or side hustles.

- **Implement standardization for efficiency, inspired by his legal reforms**: Audit your daily routine—unify tools like using one app for all notes and calendars—saving hours weekly, boosting productivity, and freeing time for hobbies that enhance well-being.

- **Embrace cultural integration like his religious policies**: In diverse teams or social circles, actively learn one custom from a colleague's background each month, such as trying a new cuisine, strengthening relationships and sparking creativity in problem-solving.

- **Overcome setbacks with Bayinnaung's post-assassination resurgence**: After a failure, like a rejected proposal, journal three lessons learned and one action step within 24 hours, turning defeats into momentum builders for long-term confidence.

- **Pursue bold visions without overextension, learning from his Siamese campaigns**: Define a "white elephant" goal—ambitious yet symbolic—and allocate resources wisely, perhaps budgeting 10% of income toward it, ensuring sustainable progress toward dreams like home ownership.

- **Foster legacy through patronage, echoing his pagoda builds**: Dedicate time weekly to mentor a younger family member or volunteer, creating ripple effects of knowledge transfer that build a supportive community around you.

To apply this holistically, follow this 90-day plan: Week 1-4: Assess your "kingdom"—list strengths, weaknesses, and allies; journal daily on historical parallels. Week 5-8: Launch "conquests"—tackle one personal or professional goal with tactical steps, tracking progress. Week 9-12: Integrate and reflect—standardize habits, build networks, and celebrate wins with a ritual, like a special meal. Repeat quarterly, adapting as Bayinnaung did. This isn't just history; it's your roadmap to empowerment, proving that from ancient crowns come modern victories.

Yet, beyond the annals, Bayinnaung's life distills timeless principles. In an age of personal reinvention, his ascent from obscurity to dominance inspires. Here's how you can channel his outcomes—unity through vision, resilience in adversity, strategic expansion—into your daily life for profound benefits.

- **Cultivate unbreakable alliances like Bayinnaung's bond with Tabinshwehti**: Start by identifying one key mentor or peer in your professional network this week; schedule a coffee chat to share goals and offer mutual support, fostering a "brother-in-arms" dynamic that accelerates career growth and emotional resilience.

- **Master tactical adaptability from his battlefield innovations**: When facing a work deadline or personal challenge, break it into phases like his river-valley campaigns—outline steps on paper, anticipate obstacles, and pivot quickly, reducing stress and increasing success rates by 30% through structured planning.

- **Build your "empire" through incremental conquests akin to his Shan integrations**: Set a monthly goal to acquire one new skill, such as learning a language app for 15 minutes daily, mirroring how he incorporated diverse states, leading to broader opportunities like job promotions or side hustles.

- **Implement standardization for efficiency, inspired by his legal reforms**: Audit your daily routine—unify tools like using one app for all notes and calendars—saving hours weekly, boosting productivity, and freeing time for hobbies that enhance well-being.

- **Embrace cultural integration like his religious policies**: In diverse teams or social circles, actively learn one custom from a colleague's background each month, such as trying a new cuisine, strengthening relationships and sparking creativity in problem-solving.

- **Overcome setbacks with Bayinnaung's post-assassination resurgence**: After a failure, like a rejected proposal, journal three lessons learned and one action step within 24 hours, turning defeats into momentum builders for long-term confidence.

- **Pursue bold visions without overextension, learning from his Siamese campaigns**: Define a "white elephant" goal—ambitious yet symbolic—and allocate resources wisely, perhaps budgeting 10% of income toward it, ensuring sustainable progress toward dreams like home ownership.

- **Foster legacy through patronage, echoing his pagoda builds**: Dedicate time weekly to mentor a younger family member or volunteer, creating ripple effects of knowledge transfer that build a supportive community around you.

To apply this holistically, follow this 90-day plan: Week 1-4: Assess your "kingdom"—list strengths, weaknesses, and allies; journal daily on historical parallels. Week 5-8: Launch "conquests"—tackle one personal or professional goal with tactical steps, tracking progress. Week 9-12: Integrate and reflect—standardize habits, build networks, and celebrate wins with a ritual, like a special meal. Repeat quarterly, adapting as Bayinnaung did. This isn't just history; it's your roadmap to empowerment, proving that from ancient crowns come modern victories.

Life in Toungoo Palace was no idle affair. From an early age, Bayinnaung was immersed in a rigorous education alongside Tabinshwehti, mastering the arts of war that defined Burmese nobility. They trained in martial arts, honing skills in swordsmanship and hand-to-hand combat. Horseback riding taught them speed and agility, while elephant riding—essential for commanding in Southeast Asian warfare—instilled a sense of commanding presence atop these massive beasts. Strategy sessions delved into tactics, logistics, and the psychology of battle, drawing from ancient texts and real-world skirmishes. Bayinnaung and Tabinshwehti forged a bond deeper than brotherhood; they became confidants, sharing dreams of glory amid the kingdom's precarious position. Toungoo, a small vassal state, was sandwiched between powerful rivals: the crumbling Ava kingdom to the north, dominated by Shan confederations, and the prosperous Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy to the south. The 16th century in Burma was a cauldron of chaos following the fall of the Pagan Empire centuries earlier. Fragmentation reigned, with ethnic groups—Burmans, Mons, Shans, and others—vying for control. The Shan states, a loose confederation of hill principalities, had sacked Ava in 1527, scattering Burmese power. Into this void stepped Toungoo under King Mingyinyo, Tabinshwehti's father, who began modest expansions. But it was Tabinshwehti, ascending in 1530 at age 14, who ignited the fire of conquest. Bayinnaung, just a year older, became his right-hand man, earning the title "Bayinnaung" meaning "King's Elder Brother" for his pivotal role in early campaigns. Their first major test came against Hanthawaddy, the wealthy Mon kingdom controlling the Irrawaddy Delta's trade routes. Initial assaults from 1534 to 1537 faltered against Hanthawaddy's fortified defenses and Portuguese mercenaries armed with firearms—a novelty in the region. Undeterred, Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung refined their approach. In 1538, at the Battle of Naungyo, Bayinnaung's light infantry outmaneuvered a larger Hanthawaddy force, using guerrilla tactics to disrupt supply lines and force a retreat. This victory opened the gates to Pegu, Hanthawaddy's capital, which fell in 1539 after a grueling siege. The conquest brought immense wealth: teak forests, rice paddies, and ports teeming with Indian Ocean trade.

Emboldened, the duo turned westward to Prome and southward to Martaban, incorporating Mon lands into Toungoo's fold. By 1542, at the Battle of Padaung Pass, Bayinnaung's forces crushed an alliance of Arakan and Prome, showcasing his tactical genius in mountainous terrain. Elephants charged through narrow defiles, while archers rained arrows from elevated positions. Further north, the 1544 Battle of Salin saw them repel Shan incursions, capturing the ancient city of Pagan—symbolic heart of Burmese identity. Yet, not all campaigns succeeded. The 1545-1547 invasion of Arakan bogged down in sieges at Mrauk-U, where Arakanese defenses, bolstered by Portuguese cannons, proved impenetrable. Similarly, the 1547-1549 push into Siam (Ayutthaya Kingdom) reached the gates of Ayutthaya but withdrew due to disease and overextended supplies. Tabinshwehti's reign peaked with these expansions, but personal demons unraveled it. Plagued by alcoholism and paranoia, he alienated allies. In April 1550, while hunting elephants near Prome, he was assassinated by Mon bodyguards loyal to Smim Sawhtut, a pretender. Chaos erupted: rebellions flared in Toungoo, Prome, and Pegu, while Shan states eyed reconquest. Bayinnaung, then viceroy of Toungoo, stepped into the breach. With a core of loyal troops, he besieged Toungoo in September 1550, forcing its surrender by January 1551. Prome fell after a five-month siege in August 1551, though Bayinnaung later regretted executing its ruler, Minkhaung. Pagan submitted swiftly in September 1551. The decisive clash came against Smim Htaw, who had seized Pegu. In February 1552, Bayinnaung's army marched south, engaging in a legendary single combat where he personally slew Smim Htaw in elephant-back duel—a scene immortalized in Burmese lore. By March 1552, Pegu was his, and Lower Burma stabilized. He relocated the capital to Pegu for its strategic port access, beginning grand constructions: a new palace, Kanbawzathadi, with gilded halls and moats stocked with crocodiles. Bayinnaung's formal coronation on January 12, 1554—Thursday, the 10th waxing of Tabodwe in the Burmese calendar 915 ME—was a spectacle of symbolism. Held in Pegu's grand hall, it featured rituals blending Buddhist blessings and animist traditions. Priests chanted sutras, elephants trumpeted, and dancers performed ancient rites. He took the regnal name Thiri Thudhamma Yaza, signifying "Glorious King of the Dharma." His chief queen, Atula Thiri Maha Yaza Dewi (known as Thakin Gyi), was crowned Agga Mahethi beside him, underscoring the dynasty's stability. The event drew envoys from Shan states and Mon nobles, signaling unity. This wasn't mere pageantry; it legitimized his rule, drawing on Pagan-era traditions to project divine mandate. Post-coronation, Bayinnaung unleashed a whirlwind of conquests, expanding Toungoo into an empire spanning modern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and parts of India and China. In 1554-1555, he invaded Upper Burma with 18,000 men, splitting forces along the Sittaung and Irrawaddy rivers. Ava fell on January 22, 1555, after Shan defenders fled. He purged disloyal elements but pardoned many, integrating survivors. By 1557, he subdued cis-Salween Shan states: Hsipaw (Thibaw), Momeik, and Mogok in January; Mohnyin and Mogaung in March; Mone, Nyaungshwe, and Mobye by November. Rebellions were crushed with Lan Na's aid, a northern Thai kingdom.

In 1558, Lan Na itself submitted: Chiang Mai's ruler Mekuti surrendered on April 2 without battle, fearing Bayinnaung's reputation. He reinforced it against Lan Xang (Laos) incursions. Chinese Shan states followed: Theinni in July 1558, Mowun, Kaingma, Sanda, and Latha by early 1559. Manipur, in northeast India, fell in February 1560 to a 10,000-man force under Binnya Dala, its raja yielding tribute. Trans-Salween campaigns in 1562-1563 targeted Kengtung (December 1562) and the Taping valley (March-April 1563), brushing against Ming China but avoiding full conflict. The crown jewel was Siam: In July 1563, Bayinnaung demanded white elephants—symbols of royalty—from Ayutthaya. Refusal sparked invasion with 60,000 troops on November 1. Kamphaeng Phet fell December 4, followed by Sukhothai, Phitsanulok, Sawankhalok, and Phichit. Ayutthaya's siege began February 7, 1564; the city surrendered February 18. Bayinnaung installed Mahinthrathirat as vassal, carting off treasures and artisans. Lan Na rebelled in 1564, prompting a 64,000-man response; Mekuti resubmitted November 25. Bayinnaung appointed Visuddhadevi, a loyalist, as ruler. Lan Xang followed in 1565: Vientiane captured January 2, but King Setthathirath fled to guerrilla warfare, forcing withdrawal by August amid losses. Maintenance wars defined the 1568-1577 period. Siamese and Lan Xang revolts in 1568-1569 saw Bayinnaung defeat Setthathirath on May 8, 1569, and capture Ayutthaya August 2 via a spy's betrayal. He enthroned Maha Thammarachathirat. Lan Xang's 1569-1570 guerrilla dragged on, with heavy casualties. Northern Shan uprisings in 1571-1572 were quashed. Further Lan Xang invasions in 1572-1573 failed under Binnya Dala, who was exiled. The 1574-1575 campaign with 34,000 men seized Vientiane December 6, installing Voravongsa I. Shan rebels met brutal ends in 1575-1577, with Mogaung's saopha executed and survivors enslaved September 30, 1577. Late years saw plans for Arakan: Sandoway occupied November 1580, but Bayinnaung died October 10, 1581, before full invasion. His death at 65, possibly from illness amid preparations, left an empire teetering.

Bayinnaung's administration followed the mandala model—concentric circles of influence radiating from the king. He ruled Pegu directly with Mon advisors like Binnya Dala (1559-1573). Reforms integrated Shan states: Saophas retained regalia but could be removed; their sons served as palace pages, blending education and hostage-taking. This curbed raids into Upper Burma, a plague since the 13th century, enduring until 1885. He standardized laws via texts like *Dhammathat Kyaw*, *Kosaungchok*, and *Hanthawaddy Hsinbyumyashin Hpyat-hton*. In Siam, he imposed the Burmese calendar and customary law, lasting until 1889. Weights and measures—cubit, tical, basket—were unified, boosting trade. Economically, control of ports like Syriam, Dala, and Martaban fueled prosperity. Rice exports, jewels, and teak flowed, while resettlements of captives from Laos and Siam bolstered labor. Pegu's 1568 rebuild featured 20 gates named for vassals, symbolizing hegemony. Religiously, as a Theravada Buddhist, Bayinnaung championed orthodoxy from Hanthawaddy's Dhammazedi tradition. He distributed scriptures, fed monks, and built pagodas: Mahazedi in Pegu (completed 1561), a spire on Shwedagon (1564). Ordinations at Kalyani Hall ensured purity. He banned human and animal sacrifices, including Shan funeral rites, and nat (spirit) worship, though unsuccessfully. In 1560, he tried acquiring Buddha's Tooth Relic from Portuguese Goa, failing. In the 1570s, he aided Ceylon against Portuguese threats, sending troops in 1576 and receiving relic replicas. Donations to Shwedagon, Shwemawdaw, and Kyaiktiyo glittered with jewels. Bayinnaung's relations with neighbors were predatory yet pragmatic. Lan Na vassals like Mekuti and Visuddhadevi governed under oversight. Siamese kings Mahinthrathirat and Maha Thammarachathirat paid tribute. Lan Xang's Maing Pat Sawbwa and Voravongsa I were puppets. Cultural exchanges flourished: Lao and Shan artisans enriched Burmese arts, while Burmese law spread eastward. His legacy? The empire crumbled post-death—Ava revolted 1583, Siam broke free 1584, all lost by 1599 under weak successors like Nanda Bayin. Yet, Shan integration stabilized Burma for centuries. In Thailand, he's the "Conqueror of Ten Directions," a figure of awe and resentment. Modern Myanmar honors him with statues, bridges, and markets; he's featured in games like *Age of Empires II* and films. Historians like Victor Lieberman highlight his role in Southeast Asian integration, though ethnic tensions lingered. Bayinnaung's story, spanning from palm-climber's son to emperor, pulses with the raw energy of history's underdogs. His conquests weren't bloodless—thousands perished in sieges and marches—but they unified a mosaic of peoples, fostering trade and culture amid warfare. Educational gems abound: the mandala system's flexibility, the power of standardized laws, the interplay of religion and statecraft. Fun anecdotes pepper the tale, like his elephant duels or relic quests, reminding us history is as thrilling as any epic novel.

Yet, beyond the annals, Bayinnaung's life distills timeless principles. In an age of personal reinvention, his ascent from obscurity to dominance inspires. Here's how you can channel his outcomes—unity through vision, resilience in adversity, strategic expansion—into your daily life for profound benefits. - **Cultivate unbreakable alliances like Bayinnaung's bond with Tabinshwehti**: Start by identifying one key mentor or peer in your professional network this week; schedule a coffee chat to share goals and offer mutual support, fostering a "brother-in-arms" dynamic that accelerates career growth and emotional resilience. - **Master tactical adaptability from his battlefield innovations**: When facing a work deadline or personal challenge, break it into phases like his river-valley campaigns—outline steps on paper, anticipate obstacles, and pivot quickly, reducing stress and increasing success rates by 30% through structured planning. - **Build your "empire" through incremental conquests akin to his Shan integrations**: Set a monthly goal to acquire one new skill, such as learning a language app for 15 minutes daily, mirroring how he incorporated diverse states, leading to broader opportunities like job promotions or side hustles. - **Implement standardization for efficiency, inspired by his legal reforms**: Audit your daily routine—unify tools like using one app for all notes and calendars—saving hours weekly, boosting productivity, and freeing time for hobbies that enhance well-being. - **Embrace cultural integration like his religious policies**: In diverse teams or social circles, actively learn one custom from a colleague's background each month, such as trying a new cuisine, strengthening relationships and sparking creativity in problem-solving. - **Overcome setbacks with Bayinnaung's post-assassination resurgence**: After a failure, like a rejected proposal, journal three lessons learned and one action step within 24 hours, turning defeats into momentum builders for long-term confidence. - **Pursue bold visions without overextension, learning from his Siamese campaigns**: Define a "white elephant" goal—ambitious yet symbolic—and allocate resources wisely, perhaps budgeting 10% of income toward it, ensuring sustainable progress toward dreams like home ownership. - **Foster legacy through patronage, echoing his pagoda builds**: Dedicate time weekly to mentor a younger family member or volunteer, creating ripple effects of knowledge transfer that build a supportive community around you. To apply this holistically, follow this 90-day plan: Week 1-4: Assess your "kingdom"—list strengths, weaknesses, and allies; journal daily on historical parallels. Week 5-8: Launch "conquests"—tackle one personal or professional goal with tactical steps, tracking progress. Week 9-12: Integrate and reflect—standardize habits, build networks, and celebrate wins with a ritual, like a special meal. Repeat quarterly, adapting as Bayinnaung did. This isn't just history; it's your roadmap to empowerment, proving that from ancient crowns come modern victories.