Imagine a glittering metropolis, the heart of one of the world's most advanced civilizations, crumbling under the hooves of invading horsemen in a single, fateful day. On January 9, 1127, the grand city of Bianjing—known today as Kaifeng—fell to the relentless forces of the Jin dynasty, marking the humiliating end of the Northern Song era in China. This wasn't just a military defeat; it was a cataclysm that saw emperors stripped of their divinity, thousands of royals and artisans dragged into captivity, and an empire's cultural treasures scattered like autumn leaves in a storm. The Jingkang Incident, as it's remembered, stands as a stark reminder of how fragile even the mightiest empires can be when hubris meets unpreparedness. But beyond the dust of history, this tale offers a vibrant mosaic of intrigue, betrayal, and human drama that can ignite your own path to resilience and growth today. Dive in with me as we explore this epic saga in vivid detail, then uncover how its echoes can supercharge your daily life with purpose and power.

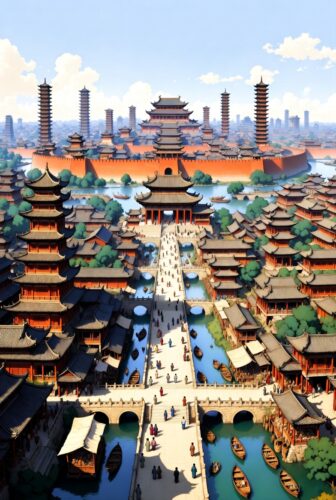

Let's start by setting the stage in the vibrant world of 12th-century China. The Northern Song dynasty, founded in 960 by Emperor Taizu after the chaotic Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, had blossomed into a golden age of innovation and prosperity. Under rulers like Emperor Taizong and Taizu's successors, the Song court emphasized civil administration over military might, fostering a bureaucracy selected through rigorous imperial examinations that prized scholarly knowledge. This era saw explosive advancements in technology: the invention of movable-type printing by Bi Sheng around 1040 revolutionized knowledge dissemination, while gunpowder was refined for fireworks and early weaponry. Compasses guided vast maritime trade networks, and the economy boomed with paper money, iron production surpassing that of Europe, and cities like Bianjing swelling to over a million inhabitants—a urban marvel unmatched globally at the time. Bianjing itself was a wonder. Encircled by massive walls stretching over 30 miles, it featured grand avenues lined with shops selling silks, teas, and exotic spices from as far as Arabia. Canals crisscrossed the city, facilitating trade via the Grand Canal, which linked the Yellow River to the Yangtze. The imperial palace, a sprawling complex of halls and gardens, housed the emperor and his court, where poets like Su Shi composed verses that still resonate in Chinese literature. Art flourished with landscape paintings capturing misty mountains and serene rivers, reflecting the Song's Neo-Confucian ideals of harmony between humans and nature. Yet, beneath this splendor lurked vulnerabilities. The Song military, weakened by policies favoring civilian control to prevent coups, relied on mercenaries and alliances rather than a standing army. Corruption festered in the court, with eunuchs and officials like Cai Jing wielding undue influence, draining resources on lavish projects while neglecting defenses.

To the north loomed threats from nomadic powers. The Liao dynasty, ruled by the Khitan people, had long extracted tributes from the Song under the Chanyuan Treaty of 1005, which ceded the Sixteen Prefectures—a strategic border region including modern Beijing—and required annual payments of silk and silver. The Song chafed under this humiliation, dreaming of reclaiming lost territories. Enter the Jurchens, a Tungusic people from the forests of Manchuria, who under chieftain Aguda founded the Jin dynasty in 1115. Fierce warriors skilled in cavalry tactics, the Jurchens resented Khitan domination and rose in rebellion, capturing Liao cities with startling speed.

The pivotal alliance formed in 1120 under the "Alliance Conducted at Sea." Song envoys, navigating treacherous waters to avoid Liao territory, met Jin representatives to plot the Liao's downfall. The deal: Joint attacks, with Jin claiming northern Liao lands and Song regaining the Sixteen Prefectures. Emperor Huizong, an artist-emperor more passionate about calligraphy and painting than statecraft, approved the pact, seeing it as a chance to erase past shames. Led by the eunuch general Tong Guan, Song forces demolished a defensive forest barrier along the border—a shortsighted move that exposed their vulnerabilities. In 1121-1122, Jin armies sacked the Liao capital at Shangjing (modern Bairin Left Banner in Inner Mongolia), effectively dismantling the Liao empire. But when Song troops advanced, they suffered humiliating defeats, revealing their military ineptitude.

The Jin, now unchallenged in the north, turned their gaze southward. Tensions escalated in 1123 when Jin general Zhang Jue defected to the Song, bringing control of Pingzhou Prefecture inside the Great Wall. The Song court welcomed him with titles and lands, ignoring Jin demands for his return. Jin forces attacked, and despite a brief Song victory, Zhang Jue was executed in a botched ruse involving a fake head. This betrayal fueled Jin Emperor Taizong's wrath. By autumn 1125, he ordered a full invasion, dividing his armies into eastern and western prongs: Wanyan Zongwang leading the east, Wanyan Zonghan the west.

Bianjing itself was a wonder. Encircled by massive walls stretching over 30 miles, it featured grand avenues lined with shops selling silks, teas, and exotic spices from as far as Arabia. Canals crisscrossed the city, facilitating trade via the Grand Canal, which linked the Yellow River to the Yangtze. The imperial palace, a sprawling complex of halls and gardens, housed the emperor and his court, where poets like Su Shi composed verses that still resonate in Chinese literature. Art flourished with landscape paintings capturing misty mountains and serene rivers, reflecting the Song's Neo-Confucian ideals of harmony between humans and nature. Yet, beneath this splendor lurked vulnerabilities. The Song military, weakened by policies favoring civilian control to prevent coups, relied on mercenaries and alliances rather than a standing army. Corruption festered in the court, with eunuchs and officials like Cai Jing wielding undue influence, draining resources on lavish projects while neglecting defenses.

To the north loomed threats from nomadic powers. The Liao dynasty, ruled by the Khitan people, had long extracted tributes from the Song under the Chanyuan Treaty of 1005, which ceded the Sixteen Prefectures—a strategic border region including modern Beijing—and required annual payments of silk and silver. The Song chafed under this humiliation, dreaming of reclaiming lost territories. Enter the Jurchens, a Tungusic people from the forests of Manchuria, who under chieftain Aguda founded the Jin dynasty in 1115. Fierce warriors skilled in cavalry tactics, the Jurchens resented Khitan domination and rose in rebellion, capturing Liao cities with startling speed.

The pivotal alliance formed in 1120 under the "Alliance Conducted at Sea." Song envoys, navigating treacherous waters to avoid Liao territory, met Jin representatives to plot the Liao's downfall. The deal: Joint attacks, with Jin claiming northern Liao lands and Song regaining the Sixteen Prefectures. Emperor Huizong, an artist-emperor more passionate about calligraphy and painting than statecraft, approved the pact, seeing it as a chance to erase past shames. Led by the eunuch general Tong Guan, Song forces demolished a defensive forest barrier along the border—a shortsighted move that exposed their vulnerabilities. In 1121-1122, Jin armies sacked the Liao capital at Shangjing (modern Bairin Left Banner in Inner Mongolia), effectively dismantling the Liao empire. But when Song troops advanced, they suffered humiliating defeats, revealing their military ineptitude.

The Jin, now unchallenged in the north, turned their gaze southward. Tensions escalated in 1123 when Jin general Zhang Jue defected to the Song, bringing control of Pingzhou Prefecture inside the Great Wall. The Song court welcomed him with titles and lands, ignoring Jin demands for his return. Jin forces attacked, and despite a brief Song victory, Zhang Jue was executed in a botched ruse involving a fake head. This betrayal fueled Jin Emperor Taizong's wrath. By autumn 1125, he ordered a full invasion, dividing his armies into eastern and western prongs: Wanyan Zongwang leading the east, Wanyan Zonghan the west. The first siege of Bianjing unfolded in early 1126. Zongwang's eastern army swept through cities like Qinhuangdao, Baoding, and Zhengding, with many Song commanders surrendering without a fight. Zonghan's western force stalled at strongholds like Datong and Taiyuan but pressed on. As Jin cavalry crossed the frozen Yellow River, panic gripped the capital. Emperor Huizong, overwhelmed, abdicated to his son Qinzong on December 23, 1125, and fled southward disguised as a commoner, leaving the 25-year-old Qinzong to face the storm. The young emperor rallied defenses, but the siege was grueling. Jin horsemen, ill-suited for urban warfare, bombarded the walls with catapults and fire arrows, while inside, famine and disease ravaged the populace.

Qinzong dispatched his brother Zhao Gou (later Emperor Gaozong) as a hostage to negotiate peace. The terms were brutal: Cession of three northern prefectures including Taiyuan, massive reparations in gold, silver, horses, and silk, and the demotion of Song to a vassal state. The Jin withdrew in March 1126, but the respite was illusory. Huizong returned to a court that resumed extravagant banquets, ignoring warnings. Experienced generals were sidelined, armies disbanded, and border garrisons neglected. Qinzong, influenced by sycophants, even entertained delusions of divine intervention, consulting a charlatan who promised heavenly armies.

The Jin, sensing weakness, struck again in September 1126 after intercepting a secret Song missive to remnant Liao forces proposing an anti-Jin alliance. Taizong mobilized 150,000 troops, far outnumbering Song's depleted 70,000 defenders. Zonghan's western army captured Datong in a month, then Luoyang and Zhengzhou fell with minimal resistance. Zongwang's eastern force razed Baoding and Dingzhou, crossing the Yellow River in November and pillaging Qingfeng and Puyang by December. By mid-December, the armies converged on Bianjing.

The first siege of Bianjing unfolded in early 1126. Zongwang's eastern army swept through cities like Qinhuangdao, Baoding, and Zhengding, with many Song commanders surrendering without a fight. Zonghan's western force stalled at strongholds like Datong and Taiyuan but pressed on. As Jin cavalry crossed the frozen Yellow River, panic gripped the capital. Emperor Huizong, overwhelmed, abdicated to his son Qinzong on December 23, 1125, and fled southward disguised as a commoner, leaving the 25-year-old Qinzong to face the storm. The young emperor rallied defenses, but the siege was grueling. Jin horsemen, ill-suited for urban warfare, bombarded the walls with catapults and fire arrows, while inside, famine and disease ravaged the populace.

Qinzong dispatched his brother Zhao Gou (later Emperor Gaozong) as a hostage to negotiate peace. The terms were brutal: Cession of three northern prefectures including Taiyuan, massive reparations in gold, silver, horses, and silk, and the demotion of Song to a vassal state. The Jin withdrew in March 1126, but the respite was illusory. Huizong returned to a court that resumed extravagant banquets, ignoring warnings. Experienced generals were sidelined, armies disbanded, and border garrisons neglected. Qinzong, influenced by sycophants, even entertained delusions of divine intervention, consulting a charlatan who promised heavenly armies.

The Jin, sensing weakness, struck again in September 1126 after intercepting a secret Song missive to remnant Liao forces proposing an anti-Jin alliance. Taizong mobilized 150,000 troops, far outnumbering Song's depleted 70,000 defenders. Zonghan's western army captured Datong in a month, then Luoyang and Zhengzhou fell with minimal resistance. Zongwang's eastern force razed Baoding and Dingzhou, crossing the Yellow River in November and pillaging Qingfeng and Puyang by December. By mid-December, the armies converged on Bianjing. The second siege was a nightmare. Song defenses crumbled under internal chaos: Supplies hoarded by corrupt officials, soldiers deserting en masse, and civilians starving as snow blanketed the city. Jin engineers built siege towers and battering rams, breaching outer walls. Desperate, Qinzong offered tribute and ceded more land, but Jin demanded total surrender. On January 9, 1127, the inner city fell. Jin troops stormed the palace, capturing Qinzong and the returned Huizong. The emperors were stripped, bound, and paraded as prisoners. Chaos ensued: Fires raged through markets, looters ransacked homes, and terrified residents fled.

The aftermath was even more harrowing. In March 1127, the Jin formalized the abductions. Over 14,000 people—imperial family, officials, artisans, musicians, and scholars—were marched northward in chains. The journey was lethal: Exposure, illness, and exhaustion claimed thousands. Women faced unimaginable horrors; many palace ladies committed suicide by drowning or poison to avoid violation. Empress Zhu, Qinzong's consort, took her life upon arrival in Jin territory. Survivors endured the "sheep-tugging ceremony," a humiliating ritual where they were stripped and clad in sheepskins, symbolizing submission.

In the Jin capital of Shangjing (modern Harbin), the captives were dispersed. Huizong and Qinzong lived in captivity; Huizong died in 1135, Qinzong in 1161 after decades of hardship, including a forced polo match where he witnessed the execution of a fellow ex-emperor. Princesses and concubines were distributed as spoils: Zhao Fujin, Huizong's daughter, became a consort to a Jin prince. Artisans were enslaved to transfer Song technologies, accelerating Jin's development.

The cultural toll was immense. Bianjing's imperial library, housing centuries of scrolls and printing blocks, was looted. Priceless artworks, bronze vessels, and astronomical instruments vanished. The Song economy staggered from lost talent and resources; ironworks and shipyards lay idle. Politically, the Jin installed a puppet regime called Chu in the north, but it collapsed swiftly. Zhao Gou, escaping capture, fled south and proclaimed the Southern Song dynasty in Lin'an (Hangzhou) in 1127. The new regime, though innovative—advancing naval power and porcelain—never reclaimed the north, signing the humiliating Treaty of Shaoxing in 1141, paying tribute to the Jin.

The second siege was a nightmare. Song defenses crumbled under internal chaos: Supplies hoarded by corrupt officials, soldiers deserting en masse, and civilians starving as snow blanketed the city. Jin engineers built siege towers and battering rams, breaching outer walls. Desperate, Qinzong offered tribute and ceded more land, but Jin demanded total surrender. On January 9, 1127, the inner city fell. Jin troops stormed the palace, capturing Qinzong and the returned Huizong. The emperors were stripped, bound, and paraded as prisoners. Chaos ensued: Fires raged through markets, looters ransacked homes, and terrified residents fled.

The aftermath was even more harrowing. In March 1127, the Jin formalized the abductions. Over 14,000 people—imperial family, officials, artisans, musicians, and scholars—were marched northward in chains. The journey was lethal: Exposure, illness, and exhaustion claimed thousands. Women faced unimaginable horrors; many palace ladies committed suicide by drowning or poison to avoid violation. Empress Zhu, Qinzong's consort, took her life upon arrival in Jin territory. Survivors endured the "sheep-tugging ceremony," a humiliating ritual where they were stripped and clad in sheepskins, symbolizing submission.

In the Jin capital of Shangjing (modern Harbin), the captives were dispersed. Huizong and Qinzong lived in captivity; Huizong died in 1135, Qinzong in 1161 after decades of hardship, including a forced polo match where he witnessed the execution of a fellow ex-emperor. Princesses and concubines were distributed as spoils: Zhao Fujin, Huizong's daughter, became a consort to a Jin prince. Artisans were enslaved to transfer Song technologies, accelerating Jin's development.

The cultural toll was immense. Bianjing's imperial library, housing centuries of scrolls and printing blocks, was looted. Priceless artworks, bronze vessels, and astronomical instruments vanished. The Song economy staggered from lost talent and resources; ironworks and shipyards lay idle. Politically, the Jin installed a puppet regime called Chu in the north, but it collapsed swiftly. Zhao Gou, escaping capture, fled south and proclaimed the Southern Song dynasty in Lin'an (Hangzhou) in 1127. The new regime, though innovative—advancing naval power and porcelain—never reclaimed the north, signing the humiliating Treaty of Shaoxing in 1141, paying tribute to the Jin. This division reshaped China. The Southern Song emphasized commerce and culture, birthing masterpieces like Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism, which influenced East Asia for centuries. Yet, the loss delayed technological progress; historians argue the invasions and later Mongol conquests stalled China's early capitalist tendencies, shifting global power westward. Socially, the incident intensified patriarchal norms: Women's chastity became idolized, with tales of suicides celebrated in literature, influencing foot-binding and seclusion practices.

The Jingkang saga brims with colorful characters. Emperor Huizong, a polymath who painted exquisite birds and flowers, neglected governance for his rock garden obsession, collecting bizarre stones that bankrupted the treasury. Tong Guan, the eunuch general, embodied corruption, amassing wealth while leading disastrous campaigns. On the Jin side, Wanyan Zonghan, a shrewd strategist, exploited Song divisions, while Zongwang's rapid marches showcased Jurchen mobility. Amid tragedy, heroes emerged: General Yue Fei, who later rose in the Southern Song, symbolized resistance with his tattooed vow, "Serve the country with utmost loyalty."

Intriguing anecdotes pepper the narrative. During the first siege, a Song crossbowman named Zhang Rong allegedly shot a Jin general from afar, boosting morale. Huizong's abdication letter poetically lamented his failures, blending regret with artistic flair. The abductions included storytellers and wine makers, highlighting how Jin coveted Song's cultural sophistication. One captive, a physician, treated Jin nobles, earning favor and preserving medical knowledge.

Geopolitically, the incident echoed beyond China. It weakened East Asia's balance, paving the way for Mongol expansions under Genghis Khan, who conquered the Jin in 1234 and the Southern Song in 1279. The diaspora of Song refugees spread technologies southward, enriching Vietnam and Korea. Linguistically, descendants of captives adopted Jurchen names, influencing modern Chinese surnames.

This division reshaped China. The Southern Song emphasized commerce and culture, birthing masterpieces like Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism, which influenced East Asia for centuries. Yet, the loss delayed technological progress; historians argue the invasions and later Mongol conquests stalled China's early capitalist tendencies, shifting global power westward. Socially, the incident intensified patriarchal norms: Women's chastity became idolized, with tales of suicides celebrated in literature, influencing foot-binding and seclusion practices.

The Jingkang saga brims with colorful characters. Emperor Huizong, a polymath who painted exquisite birds and flowers, neglected governance for his rock garden obsession, collecting bizarre stones that bankrupted the treasury. Tong Guan, the eunuch general, embodied corruption, amassing wealth while leading disastrous campaigns. On the Jin side, Wanyan Zonghan, a shrewd strategist, exploited Song divisions, while Zongwang's rapid marches showcased Jurchen mobility. Amid tragedy, heroes emerged: General Yue Fei, who later rose in the Southern Song, symbolized resistance with his tattooed vow, "Serve the country with utmost loyalty."

Intriguing anecdotes pepper the narrative. During the first siege, a Song crossbowman named Zhang Rong allegedly shot a Jin general from afar, boosting morale. Huizong's abdication letter poetically lamented his failures, blending regret with artistic flair. The abductions included storytellers and wine makers, highlighting how Jin coveted Song's cultural sophistication. One captive, a physician, treated Jin nobles, earning favor and preserving medical knowledge.

Geopolitically, the incident echoed beyond China. It weakened East Asia's balance, paving the way for Mongol expansions under Genghis Khan, who conquered the Jin in 1234 and the Southern Song in 1279. The diaspora of Song refugees spread technologies southward, enriching Vietnam and Korea. Linguistically, descendants of captives adopted Jurchen names, influencing modern Chinese surnames. Now, shifting gears to the motivational spark: While the Jingkang Incident paints a portrait of downfall, its core lessons—on vigilance, adaptability, and rebirth—can transform your life today. Think of it as a ancient blueprint for personal empire-building. In a world of uncertainties, from career shifts to global upheavals, drawing from this history equips you to avoid pitfalls and seize opportunities.

Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life:

- **Cultivate Strategic Alliances Wisely**: The Song's hasty pact with the Jin backfired due to unequal power dynamics. In your life, evaluate partnerships—be it in business, friendships, or romance—for mutual benefit and trust. Avoid deals that expose your weaknesses without safeguards.

- **Prioritize Preparedness Over Complacency**: Post-first siege, the Song dismantled defenses, inviting disaster. Apply this by building "buffers" like emergency savings, skill diversification, or health routines to weather personal storms.

- **Embrace Humility in Leadership**: Huizong's artistic distractions blinded him to realities. Stay grounded; regularly self-assess your decisions, seeking feedback to avoid ego-driven errors.

- **Foster Resilience Through Adversity**: Captives who survived adapted, some thriving in new roles. Turn setbacks into growth by reframing failures as learning curves, building mental toughness.

- **Value Cultural and Intellectual Capital**: The loss of artisans crippled Song recovery. Invest in your knowledge—read widely, learn new skills—to become indispensable in your field.

- **Promote Unity in Crisis**: Song court infighting accelerated the fall. In teams or family, encourage open communication to resolve conflicts swiftly.

- **Learn from Historical Cycles**: Dynasties rise and fall; recognize patterns in your life cycles to anticipate changes and pivot effectively.

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Jingkang's wisdom into your routine, turning history into your personal superpower:

Now, shifting gears to the motivational spark: While the Jingkang Incident paints a portrait of downfall, its core lessons—on vigilance, adaptability, and rebirth—can transform your life today. Think of it as a ancient blueprint for personal empire-building. In a world of uncertainties, from career shifts to global upheavals, drawing from this history equips you to avoid pitfalls and seize opportunities.

Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life:

- **Cultivate Strategic Alliances Wisely**: The Song's hasty pact with the Jin backfired due to unequal power dynamics. In your life, evaluate partnerships—be it in business, friendships, or romance—for mutual benefit and trust. Avoid deals that expose your weaknesses without safeguards.

- **Prioritize Preparedness Over Complacency**: Post-first siege, the Song dismantled defenses, inviting disaster. Apply this by building "buffers" like emergency savings, skill diversification, or health routines to weather personal storms.

- **Embrace Humility in Leadership**: Huizong's artistic distractions blinded him to realities. Stay grounded; regularly self-assess your decisions, seeking feedback to avoid ego-driven errors.

- **Foster Resilience Through Adversity**: Captives who survived adapted, some thriving in new roles. Turn setbacks into growth by reframing failures as learning curves, building mental toughness.

- **Value Cultural and Intellectual Capital**: The loss of artisans crippled Song recovery. Invest in your knowledge—read widely, learn new skills—to become indispensable in your field.

- **Promote Unity in Crisis**: Song court infighting accelerated the fall. In teams or family, encourage open communication to resolve conflicts swiftly.

- **Learn from Historical Cycles**: Dynasties rise and fall; recognize patterns in your life cycles to anticipate changes and pivot effectively.

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Jingkang's wisdom into your routine, turning history into your personal superpower:

**Reflect on Past Alliances (Week 1)**: Journal about a recent partnership or decision that went awry. Analyze what went wrong, drawing parallels to the Song-Jin pact. Set criteria for future alliances, like "Does this align with my long-term goals?"

**Build Your Defenses (Weeks 2-4)**: Audit your vulnerabilities—financial, emotional, professional. Create a "siege kit": Save 10% of income monthly, learn one new skill quarterly (e.g., coding via online courses), and establish a weekly health ritual like meditation or exercise.

**Practice Humble Leadership (Ongoing)**: Weekly, seek input from a mentor or peer on a key decision. Read biographies of adaptable leaders, like Zhao Gou's Southern Song revival, to inspire balanced ambition.

**Simulate Adversity (Monthly)**: Role-play scenarios, such as job loss, using Jingkang's abductions as metaphor. Brainstorm adaptation strategies, building confidence in your resilience.

**Enrich Your Cultural Arsenal (Daily)**: Dedicate 30 minutes to learning—books on history, art, or tech. Share insights in a blog or discussion group, mirroring how Song artisans preserved knowledge.

**Foster Unity Networks (Bi-Weekly)**: Host gatherings or virtual check-ins with your circle to discuss challenges openly, preventing "court intrigues" in your life.

**Review and Adapt (Quarterly)**: Revisit this plan, measuring progress (e.g., "Did I avoid a bad alliance?"). Celebrate wins with a fun ritual, like a historical-themed dinner, to keep motivation high.

By weaving these threads from 1127 into your fabric, you'll not only honor the past but forge a future of unshakeable strength. The Jingkang Incident teaches that from ashes, new dynasties—and personal legends—arise. So, rise up, channel that ancient fire, and conquer your own horizons!

Bianjing itself was a wonder. Encircled by massive walls stretching over 30 miles, it featured grand avenues lined with shops selling silks, teas, and exotic spices from as far as Arabia. Canals crisscrossed the city, facilitating trade via the Grand Canal, which linked the Yellow River to the Yangtze. The imperial palace, a sprawling complex of halls and gardens, housed the emperor and his court, where poets like Su Shi composed verses that still resonate in Chinese literature. Art flourished with landscape paintings capturing misty mountains and serene rivers, reflecting the Song's Neo-Confucian ideals of harmony between humans and nature. Yet, beneath this splendor lurked vulnerabilities. The Song military, weakened by policies favoring civilian control to prevent coups, relied on mercenaries and alliances rather than a standing army. Corruption festered in the court, with eunuchs and officials like Cai Jing wielding undue influence, draining resources on lavish projects while neglecting defenses. To the north loomed threats from nomadic powers. The Liao dynasty, ruled by the Khitan people, had long extracted tributes from the Song under the Chanyuan Treaty of 1005, which ceded the Sixteen Prefectures—a strategic border region including modern Beijing—and required annual payments of silk and silver. The Song chafed under this humiliation, dreaming of reclaiming lost territories. Enter the Jurchens, a Tungusic people from the forests of Manchuria, who under chieftain Aguda founded the Jin dynasty in 1115. Fierce warriors skilled in cavalry tactics, the Jurchens resented Khitan domination and rose in rebellion, capturing Liao cities with startling speed. The pivotal alliance formed in 1120 under the "Alliance Conducted at Sea." Song envoys, navigating treacherous waters to avoid Liao territory, met Jin representatives to plot the Liao's downfall. The deal: Joint attacks, with Jin claiming northern Liao lands and Song regaining the Sixteen Prefectures. Emperor Huizong, an artist-emperor more passionate about calligraphy and painting than statecraft, approved the pact, seeing it as a chance to erase past shames. Led by the eunuch general Tong Guan, Song forces demolished a defensive forest barrier along the border—a shortsighted move that exposed their vulnerabilities. In 1121-1122, Jin armies sacked the Liao capital at Shangjing (modern Bairin Left Banner in Inner Mongolia), effectively dismantling the Liao empire. But when Song troops advanced, they suffered humiliating defeats, revealing their military ineptitude. The Jin, now unchallenged in the north, turned their gaze southward. Tensions escalated in 1123 when Jin general Zhang Jue defected to the Song, bringing control of Pingzhou Prefecture inside the Great Wall. The Song court welcomed him with titles and lands, ignoring Jin demands for his return. Jin forces attacked, and despite a brief Song victory, Zhang Jue was executed in a botched ruse involving a fake head. This betrayal fueled Jin Emperor Taizong's wrath. By autumn 1125, he ordered a full invasion, dividing his armies into eastern and western prongs: Wanyan Zongwang leading the east, Wanyan Zonghan the west.

The first siege of Bianjing unfolded in early 1126. Zongwang's eastern army swept through cities like Qinhuangdao, Baoding, and Zhengding, with many Song commanders surrendering without a fight. Zonghan's western force stalled at strongholds like Datong and Taiyuan but pressed on. As Jin cavalry crossed the frozen Yellow River, panic gripped the capital. Emperor Huizong, overwhelmed, abdicated to his son Qinzong on December 23, 1125, and fled southward disguised as a commoner, leaving the 25-year-old Qinzong to face the storm. The young emperor rallied defenses, but the siege was grueling. Jin horsemen, ill-suited for urban warfare, bombarded the walls with catapults and fire arrows, while inside, famine and disease ravaged the populace. Qinzong dispatched his brother Zhao Gou (later Emperor Gaozong) as a hostage to negotiate peace. The terms were brutal: Cession of three northern prefectures including Taiyuan, massive reparations in gold, silver, horses, and silk, and the demotion of Song to a vassal state. The Jin withdrew in March 1126, but the respite was illusory. Huizong returned to a court that resumed extravagant banquets, ignoring warnings. Experienced generals were sidelined, armies disbanded, and border garrisons neglected. Qinzong, influenced by sycophants, even entertained delusions of divine intervention, consulting a charlatan who promised heavenly armies. The Jin, sensing weakness, struck again in September 1126 after intercepting a secret Song missive to remnant Liao forces proposing an anti-Jin alliance. Taizong mobilized 150,000 troops, far outnumbering Song's depleted 70,000 defenders. Zonghan's western army captured Datong in a month, then Luoyang and Zhengzhou fell with minimal resistance. Zongwang's eastern force razed Baoding and Dingzhou, crossing the Yellow River in November and pillaging Qingfeng and Puyang by December. By mid-December, the armies converged on Bianjing.

The second siege was a nightmare. Song defenses crumbled under internal chaos: Supplies hoarded by corrupt officials, soldiers deserting en masse, and civilians starving as snow blanketed the city. Jin engineers built siege towers and battering rams, breaching outer walls. Desperate, Qinzong offered tribute and ceded more land, but Jin demanded total surrender. On January 9, 1127, the inner city fell. Jin troops stormed the palace, capturing Qinzong and the returned Huizong. The emperors were stripped, bound, and paraded as prisoners. Chaos ensued: Fires raged through markets, looters ransacked homes, and terrified residents fled. The aftermath was even more harrowing. In March 1127, the Jin formalized the abductions. Over 14,000 people—imperial family, officials, artisans, musicians, and scholars—were marched northward in chains. The journey was lethal: Exposure, illness, and exhaustion claimed thousands. Women faced unimaginable horrors; many palace ladies committed suicide by drowning or poison to avoid violation. Empress Zhu, Qinzong's consort, took her life upon arrival in Jin territory. Survivors endured the "sheep-tugging ceremony," a humiliating ritual where they were stripped and clad in sheepskins, symbolizing submission. In the Jin capital of Shangjing (modern Harbin), the captives were dispersed. Huizong and Qinzong lived in captivity; Huizong died in 1135, Qinzong in 1161 after decades of hardship, including a forced polo match where he witnessed the execution of a fellow ex-emperor. Princesses and concubines were distributed as spoils: Zhao Fujin, Huizong's daughter, became a consort to a Jin prince. Artisans were enslaved to transfer Song technologies, accelerating Jin's development. The cultural toll was immense. Bianjing's imperial library, housing centuries of scrolls and printing blocks, was looted. Priceless artworks, bronze vessels, and astronomical instruments vanished. The Song economy staggered from lost talent and resources; ironworks and shipyards lay idle. Politically, the Jin installed a puppet regime called Chu in the north, but it collapsed swiftly. Zhao Gou, escaping capture, fled south and proclaimed the Southern Song dynasty in Lin'an (Hangzhou) in 1127. The new regime, though innovative—advancing naval power and porcelain—never reclaimed the north, signing the humiliating Treaty of Shaoxing in 1141, paying tribute to the Jin.

This division reshaped China. The Southern Song emphasized commerce and culture, birthing masterpieces like Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism, which influenced East Asia for centuries. Yet, the loss delayed technological progress; historians argue the invasions and later Mongol conquests stalled China's early capitalist tendencies, shifting global power westward. Socially, the incident intensified patriarchal norms: Women's chastity became idolized, with tales of suicides celebrated in literature, influencing foot-binding and seclusion practices. The Jingkang saga brims with colorful characters. Emperor Huizong, a polymath who painted exquisite birds and flowers, neglected governance for his rock garden obsession, collecting bizarre stones that bankrupted the treasury. Tong Guan, the eunuch general, embodied corruption, amassing wealth while leading disastrous campaigns. On the Jin side, Wanyan Zonghan, a shrewd strategist, exploited Song divisions, while Zongwang's rapid marches showcased Jurchen mobility. Amid tragedy, heroes emerged: General Yue Fei, who later rose in the Southern Song, symbolized resistance with his tattooed vow, "Serve the country with utmost loyalty." Intriguing anecdotes pepper the narrative. During the first siege, a Song crossbowman named Zhang Rong allegedly shot a Jin general from afar, boosting morale. Huizong's abdication letter poetically lamented his failures, blending regret with artistic flair. The abductions included storytellers and wine makers, highlighting how Jin coveted Song's cultural sophistication. One captive, a physician, treated Jin nobles, earning favor and preserving medical knowledge. Geopolitically, the incident echoed beyond China. It weakened East Asia's balance, paving the way for Mongol expansions under Genghis Khan, who conquered the Jin in 1234 and the Southern Song in 1279. The diaspora of Song refugees spread technologies southward, enriching Vietnam and Korea. Linguistically, descendants of captives adopted Jurchen names, influencing modern Chinese surnames.

Now, shifting gears to the motivational spark: While the Jingkang Incident paints a portrait of downfall, its core lessons—on vigilance, adaptability, and rebirth—can transform your life today. Think of it as a ancient blueprint for personal empire-building. In a world of uncertainties, from career shifts to global upheavals, drawing from this history equips you to avoid pitfalls and seize opportunities. Here's how you benefit from this historical fact in your individual life: - **Cultivate Strategic Alliances Wisely**: The Song's hasty pact with the Jin backfired due to unequal power dynamics. In your life, evaluate partnerships—be it in business, friendships, or romance—for mutual benefit and trust. Avoid deals that expose your weaknesses without safeguards. - **Prioritize Preparedness Over Complacency**: Post-first siege, the Song dismantled defenses, inviting disaster. Apply this by building "buffers" like emergency savings, skill diversification, or health routines to weather personal storms. - **Embrace Humility in Leadership**: Huizong's artistic distractions blinded him to realities. Stay grounded; regularly self-assess your decisions, seeking feedback to avoid ego-driven errors. - **Foster Resilience Through Adversity**: Captives who survived adapted, some thriving in new roles. Turn setbacks into growth by reframing failures as learning curves, building mental toughness. - **Value Cultural and Intellectual Capital**: The loss of artisans crippled Song recovery. Invest in your knowledge—read widely, learn new skills—to become indispensable in your field. - **Promote Unity in Crisis**: Song court infighting accelerated the fall. In teams or family, encourage open communication to resolve conflicts swiftly. - **Learn from Historical Cycles**: Dynasties rise and fall; recognize patterns in your life cycles to anticipate changes and pivot effectively. To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to integrate Jingkang's wisdom into your routine, turning history into your personal superpower: