Imagine a city buzzing with life under a crisp winter sky, its streets alive with merchants haggling over silks and spices, artisans hammering away at intricate jewelry, and priests chanting in grand cathedrals. This was Dvin, the beating heart of medieval Armenia, a metropolis that rivaled the great cities of the East in wealth and splendor. But on the night of December 28, 893, as the clock struck midnight, the ground beneath it convulsed in a fury that would echo through centuries. The earth cracked open, swallowing homes and dreams alike, in one of the most devastating earthquakes of the medieval world. This wasn't just a natural disaster—it was a pivotal moment that altered the course of a nascent kingdom, forcing its people to rebuild from rubble and redefine their future. Today, we're diving deep into this forgotten cataclysm, exploring the rich tapestry of Armenian history that surrounded it, and drawing out timeless lessons to supercharge your own life. Buckle up for a journey that's equal parts thrilling history lesson and motivational rocket fuel.

To truly grasp the magnitude of the 893 Dvin earthquake, we need to rewind the clock and set the stage in the turbulent world of 9th-century Armenia. This land, nestled between towering mountains and fertile valleys at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, had long been a prize for empires. For nearly two centuries before 893, Armenia languished under the iron grip of Arab rule, first the Umayyads and then the Abbasids. The Abbasid Caliphate, based in distant Baghdad, treated Armenia as a frontier province called Arminiya, extracting heavy taxes and quelling revolts with brutal efficiency. Armenian nobles, known as nakharars, chafed under this yoke, their ancient lineages—families like the Mamikonians and the Bagratunis—plotting and maneuvering for autonomy. The Bagratuni dynasty, in particular, rose like a phoenix from the ashes of earlier defeats. Their story begins in the shadows of the 8th century, after the disastrous Battle of Bagrevand in 775, where Arab forces crushed a major Armenian uprising, scattering rival clans and leaving the Bagratunis as one of the few surviving powerhouses. By the 860s, Ashot Bagratuni, a shrewd and ambitious leader, had consolidated control over key territories. He played a delicate diplomatic game, balancing alliances between the Abbasid Caliphate and the resurgent Byzantine Empire to the west. In 862, the Abbasids granted him the title of "prince of princes" (ishkhan ishkhanats), acknowledging his dominance over other Armenian lords. But Ashot dreamed bigger—he wanted a crown.

The geopolitical chessboard of the era was a whirlwind of intrigue. The Byzantine Empire, under emperors like Basil I the Macedonian, was reclaiming lost territories and eyeing Armenia as a buffer against Arab incursions. Meanwhile, the Abbasids were weakening, plagued by internal rebellions and the rise of semi-independent emirs in their provinces. Ashot seized the moment. In 884 or 885, Caliph Al-Mu'tamid sent him a royal crown, officially recognizing him as King Ashot I of Armenia. Not to be outdone, Basil I dispatched his own crown, solidifying a Byzantine-Armenian alliance. This dual recognition was a masterstroke, positioning the new Bagratid Kingdom as a sovereign entity caught between two superpowers. Ashot's court moved to Bagaran initially, but Dvin—ancient, strategic, and symbolically potent—loomed as the ultimate prize.

Dvin itself was a marvel, a city with roots stretching back millennia. Founded in the 4th century by King Khosrov III Kotak of the Arsacid dynasty, it was built on the ruins of even older settlements dating to the Bronze Age. Perched along the Metsamor River, 35 kilometers south of modern Yerevan, Dvin grew into a fortified stronghold and commercial hub. By the 5th century, it had become the capital of Sassanid Persia’s Armenian province after the fall of the Arsacid kingdom in 428. Persian marzpans (governors) ruled from its palaces, blending Zoroastrian influences with emerging Christian traditions. When the Arabs conquered in 640 during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Constans II, they renamed it Dabil and made it the administrative center of Arminiya, a vast province encompassing Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan.

Under Arab rule, Dvin flourished despite the oppression. Its population swelled to around 100,000 by the 9th century, making it one of the largest cities east of Constantinople. Streets teemed with diversity: Armenian Christians, Arab Muslims, Jews, Persians, and traders from as far as China and India. The economy boomed on the back of the Great Armenian Highway, a vital artery of the Silk Road that funneled goods like textiles, armor, horses, salt, wine, and the prized cochineal dye extracted from insects in nearby Artashat. Artisans crafted exquisite wool and silk fabrics, rugs, pillows, and metalwork that were exported to Byzantine markets and Abbasid courts. Fishing in the Metsamor provided sustenance, while vineyards and orchards dotted the surrounding plains.

The Bagratuni dynasty, in particular, rose like a phoenix from the ashes of earlier defeats. Their story begins in the shadows of the 8th century, after the disastrous Battle of Bagrevand in 775, where Arab forces crushed a major Armenian uprising, scattering rival clans and leaving the Bagratunis as one of the few surviving powerhouses. By the 860s, Ashot Bagratuni, a shrewd and ambitious leader, had consolidated control over key territories. He played a delicate diplomatic game, balancing alliances between the Abbasid Caliphate and the resurgent Byzantine Empire to the west. In 862, the Abbasids granted him the title of "prince of princes" (ishkhan ishkhanats), acknowledging his dominance over other Armenian lords. But Ashot dreamed bigger—he wanted a crown.

The geopolitical chessboard of the era was a whirlwind of intrigue. The Byzantine Empire, under emperors like Basil I the Macedonian, was reclaiming lost territories and eyeing Armenia as a buffer against Arab incursions. Meanwhile, the Abbasids were weakening, plagued by internal rebellions and the rise of semi-independent emirs in their provinces. Ashot seized the moment. In 884 or 885, Caliph Al-Mu'tamid sent him a royal crown, officially recognizing him as King Ashot I of Armenia. Not to be outdone, Basil I dispatched his own crown, solidifying a Byzantine-Armenian alliance. This dual recognition was a masterstroke, positioning the new Bagratid Kingdom as a sovereign entity caught between two superpowers. Ashot's court moved to Bagaran initially, but Dvin—ancient, strategic, and symbolically potent—loomed as the ultimate prize.

Dvin itself was a marvel, a city with roots stretching back millennia. Founded in the 4th century by King Khosrov III Kotak of the Arsacid dynasty, it was built on the ruins of even older settlements dating to the Bronze Age. Perched along the Metsamor River, 35 kilometers south of modern Yerevan, Dvin grew into a fortified stronghold and commercial hub. By the 5th century, it had become the capital of Sassanid Persia’s Armenian province after the fall of the Arsacid kingdom in 428. Persian marzpans (governors) ruled from its palaces, blending Zoroastrian influences with emerging Christian traditions. When the Arabs conquered in 640 during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Constans II, they renamed it Dabil and made it the administrative center of Arminiya, a vast province encompassing Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan.

Under Arab rule, Dvin flourished despite the oppression. Its population swelled to around 100,000 by the 9th century, making it one of the largest cities east of Constantinople. Streets teemed with diversity: Armenian Christians, Arab Muslims, Jews, Persians, and traders from as far as China and India. The economy boomed on the back of the Great Armenian Highway, a vital artery of the Silk Road that funneled goods like textiles, armor, horses, salt, wine, and the prized cochineal dye extracted from insects in nearby Artashat. Artisans crafted exquisite wool and silk fabrics, rugs, pillows, and metalwork that were exported to Byzantine markets and Abbasid courts. Fishing in the Metsamor provided sustenance, while vineyards and orchards dotted the surrounding plains. Architecturally, Dvin was a testament to Armenian ingenuity. Its defensive walls, reinforced over centuries, encircled a labyrinth of stone buildings. At the heart stood the Cathedral of Saint Grigor, originally a pagan temple converted to Christianity in the 5th century. This massive basilica, measuring over 30 by 58 meters, featured a pentahedral apse, arched galleries, and intricate mosaics—the oldest surviving in Armenia, depicting the Holy Virgin in vibrant tiles. Column capitals bore fern-like reliefs, and cornices were carved with interlaced strands, blending Byzantine, Sassanid, and local styles. Nearby, the catholicos' palace housed the spiritual leader of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a figure as powerful as any king. Zoroastrian fire-temples lingered from Persian days, now overshadowed by churches and monasteries.

But Dvin's glory masked vulnerabilities. The region sat atop the volatile collision zone between the Arabian and Eurasian tectonic plates, a hotspot for seismic activity. Earthquakes had rattled the city before—in the mid-9th century, smaller tremors along the Sardarapat-Nakhichevan fault system hinted at brewing disaster. The Parackar-Dvin segment, with its oblique dextral strike-slip motion, was particularly unstable. Historians like Thomas Artsruni and Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi chronicled earlier quakes, but none prepared the inhabitants for what came on that fateful December night in 893.

Picture the scene: It's midnight on December 28. The city slumbers under a blanket of stars, perhaps illuminated by a partial lunar eclipse the previous evening, as some Armenian accounts suggest. Families huddle around hearths against the winter chill. In the catholicos' palace, clerics pore over illuminated manuscripts. Merchants count their dinars in dimly lit warehouses. Suddenly, a low rumble builds to a deafening roar. The ground heaves like a living beast, cracking open fissures that swallow streets whole. Buildings sway and collapse in cascades of stone and timber. The Cathedral of Saint Grigor, that architectural jewel, crumbles—its dome crashing down, mosaics shattering into dust. Defensive walls, meant to repel armies, buckle like paper. Landslides thunder down from the Artashat Plateau, burying villages and retreats. Bishop Grigor of Rshtunik, seeking solace in a mountain hermitage, perishes along with his entourage as rocks rain from above.

Architecturally, Dvin was a testament to Armenian ingenuity. Its defensive walls, reinforced over centuries, encircled a labyrinth of stone buildings. At the heart stood the Cathedral of Saint Grigor, originally a pagan temple converted to Christianity in the 5th century. This massive basilica, measuring over 30 by 58 meters, featured a pentahedral apse, arched galleries, and intricate mosaics—the oldest surviving in Armenia, depicting the Holy Virgin in vibrant tiles. Column capitals bore fern-like reliefs, and cornices were carved with interlaced strands, blending Byzantine, Sassanid, and local styles. Nearby, the catholicos' palace housed the spiritual leader of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a figure as powerful as any king. Zoroastrian fire-temples lingered from Persian days, now overshadowed by churches and monasteries.

But Dvin's glory masked vulnerabilities. The region sat atop the volatile collision zone between the Arabian and Eurasian tectonic plates, a hotspot for seismic activity. Earthquakes had rattled the city before—in the mid-9th century, smaller tremors along the Sardarapat-Nakhichevan fault system hinted at brewing disaster. The Parackar-Dvin segment, with its oblique dextral strike-slip motion, was particularly unstable. Historians like Thomas Artsruni and Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi chronicled earlier quakes, but none prepared the inhabitants for what came on that fateful December night in 893.

Picture the scene: It's midnight on December 28. The city slumbers under a blanket of stars, perhaps illuminated by a partial lunar eclipse the previous evening, as some Armenian accounts suggest. Families huddle around hearths against the winter chill. In the catholicos' palace, clerics pore over illuminated manuscripts. Merchants count their dinars in dimly lit warehouses. Suddenly, a low rumble builds to a deafening roar. The ground heaves like a living beast, cracking open fissures that swallow streets whole. Buildings sway and collapse in cascades of stone and timber. The Cathedral of Saint Grigor, that architectural jewel, crumbles—its dome crashing down, mosaics shattering into dust. Defensive walls, meant to repel armies, buckle like paper. Landslides thunder down from the Artashat Plateau, burying villages and retreats. Bishop Grigor of Rshtunik, seeking solace in a mountain hermitage, perishes along with his entourage as rocks rain from above. The quake's magnitude is debated—estimates range from 5.3 to 7.0 or higher, with a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent) to X (Extreme). It struck near coordinates 40°00′N 44°36′E, epicentered close to Dvin. Aftershocks ravaged the area for five harrowing days, compounding the terror. Casualty figures vary wildly in contemporary sources: Armenian chroniclers like Stepanos Taronetsi report 30,000 dead, while Arabic historians inflate it to 70,000, 150,000, or even 180,000. Modern scholars settle around 20,000 to 30,000, a staggering toll for the era. Most of Dvin's 100,000 residents were affected—only about 100 houses remained standing. Palaces, churches, markets, all lay in ruins. The Metsamor River may have flooded from disrupted banks, adding to the chaos.

Confusion in historical records adds layers of intrigue. Arabic sources called the city Dabil, leading later catalogers to misattribute the quake to Ardabil in Iran, creating a "phantom" event there. Dates fluctuate too—some say March 23 or December 24, years from 893 to 895. Armenian writers linked it to celestial omens, like the eclipse, viewing it as divine wrath. But the impact was undeniable. Dvin's defenses were obliterated, leaving it vulnerable to opportunists.

Enter the political fallout, a drama worthy of any epic saga. At the time, Smbat I Bagratuni had just been crowned king in 892, having recaptured Dvin from Arab control that same year. The earthquake stripped away his hard-won gains. With walls down and the population decimated, Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Saj, the Sajid emir of Adharbayjan (modern Azerbaijan), swooped in. The Sajids, a Persianized Turkish dynasty ruling as Abbasid governors, saw Dvin as a strategic base. Muhammad captured the city without resistance, converting it into a military outpost and imposing tribute. This humiliation stung the Bagratids, but Smbat focused on consolidation elsewhere.

The quake accelerated Dvin's decline, though it wasn't immediate. Survivors rebuilt amid the rubble, and by the 10th century, the city regained some prosperity under Bagratid oversight. Trade resumed, artisans returned, and new structures rose from the ashes. However, repeated invasions eroded its status. In 901, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj (Muhammad's brother) launched campaigns against Smbat, culminating in the king's capture, torture, and execution in 914—a grisly affair where Smbat was crucified and beheaded. His son, Ashot II "the Iron," fought back with Byzantine aid, reclaiming territories and earning the title Shahanshah (king of kings) in 919.

The quake's magnitude is debated—estimates range from 5.3 to 7.0 or higher, with a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent) to X (Extreme). It struck near coordinates 40°00′N 44°36′E, epicentered close to Dvin. Aftershocks ravaged the area for five harrowing days, compounding the terror. Casualty figures vary wildly in contemporary sources: Armenian chroniclers like Stepanos Taronetsi report 30,000 dead, while Arabic historians inflate it to 70,000, 150,000, or even 180,000. Modern scholars settle around 20,000 to 30,000, a staggering toll for the era. Most of Dvin's 100,000 residents were affected—only about 100 houses remained standing. Palaces, churches, markets, all lay in ruins. The Metsamor River may have flooded from disrupted banks, adding to the chaos.

Confusion in historical records adds layers of intrigue. Arabic sources called the city Dabil, leading later catalogers to misattribute the quake to Ardabil in Iran, creating a "phantom" event there. Dates fluctuate too—some say March 23 or December 24, years from 893 to 895. Armenian writers linked it to celestial omens, like the eclipse, viewing it as divine wrath. But the impact was undeniable. Dvin's defenses were obliterated, leaving it vulnerable to opportunists.

Enter the political fallout, a drama worthy of any epic saga. At the time, Smbat I Bagratuni had just been crowned king in 892, having recaptured Dvin from Arab control that same year. The earthquake stripped away his hard-won gains. With walls down and the population decimated, Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Saj, the Sajid emir of Adharbayjan (modern Azerbaijan), swooped in. The Sajids, a Persianized Turkish dynasty ruling as Abbasid governors, saw Dvin as a strategic base. Muhammad captured the city without resistance, converting it into a military outpost and imposing tribute. This humiliation stung the Bagratids, but Smbat focused on consolidation elsewhere.

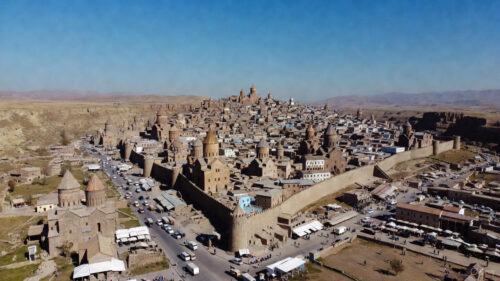

The quake accelerated Dvin's decline, though it wasn't immediate. Survivors rebuilt amid the rubble, and by the 10th century, the city regained some prosperity under Bagratid oversight. Trade resumed, artisans returned, and new structures rose from the ashes. However, repeated invasions eroded its status. In 901, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj (Muhammad's brother) launched campaigns against Smbat, culminating in the king's capture, torture, and execution in 914—a grisly affair where Smbat was crucified and beheaded. His son, Ashot II "the Iron," fought back with Byzantine aid, reclaiming territories and earning the title Shahanshah (king of kings) in 919. Under subsequent rulers like Abas I (928–953) and Ashot III "the Merciful" (953–977), the kingdom entered a golden age. Ashot III relocated the capital to Ani in 961, a move perhaps influenced by Dvin's seismic scars. Ani, perched on a triangular plateau overlooking the Akhuryan River, became a fortified wonder—dubbed the "City of 1,001 Churches" with its soaring cathedrals, massive walls, and bustling markets. Architects like Trdat designed masterpieces blending Armenian, Byzantine, and Islamic elements: domed basilicas with frescoes, vaulted halls, and intricate carvings. Monasteries such as Sanahin and Haghpat, founded by Ashot III's queen Khosrovanush, became intellectual hubs, producing philosophers like Grigor Narekatsi, whose mystical poetry still inspires.

Economically, the post-quake era saw diversification. With Dvin diminished, trade shifted north to Ani, which controlled routes from the Black Sea to Persia. Armenian merchants exported furs, timber, honey, and leather, importing luxuries like spices and gems. Feudalism deepened, with peasants (ramiks) tilling lands for noble azats, paying taxes in kind. Cultural revival bloomed: illuminated manuscripts depicted biblical scenes with vibrant miniatures, music filled churches with haunting chants, and literature flourished in classical Armenian.

Yet threats loomed. Byzantine annexations nibbled at borders—Taron in 967, Vaspurakan in 1021 under Emperor Basil II "the Bulgar-Slayer." Internal feuds weakened the realm. By the 11th century, Seljuk Turks under Alp Arslan swept in, capturing Ani in 1064 after a siege that exploited its water supply. Dvin, already a shadow, fell to Seljuks that year, then to Georgians in 1173, Khwarezmians in 1225, and finally Mongols in 1236, who razed it utterly. Excavations since 1937 have unearthed pottery, mosaics, and tools, piecing together this lost world.

The 893 earthquake wasn't just a blip—it reshaped Bagratid Armenia's trajectory, forcing adaptation and innovation. From the ruins rose Ani, symbolizing Armenian endurance amid empires' clashes. This resilience, forged in fire and tremor, offers profound insights for us today.

Under subsequent rulers like Abas I (928–953) and Ashot III "the Merciful" (953–977), the kingdom entered a golden age. Ashot III relocated the capital to Ani in 961, a move perhaps influenced by Dvin's seismic scars. Ani, perched on a triangular plateau overlooking the Akhuryan River, became a fortified wonder—dubbed the "City of 1,001 Churches" with its soaring cathedrals, massive walls, and bustling markets. Architects like Trdat designed masterpieces blending Armenian, Byzantine, and Islamic elements: domed basilicas with frescoes, vaulted halls, and intricate carvings. Monasteries such as Sanahin and Haghpat, founded by Ashot III's queen Khosrovanush, became intellectual hubs, producing philosophers like Grigor Narekatsi, whose mystical poetry still inspires.

Economically, the post-quake era saw diversification. With Dvin diminished, trade shifted north to Ani, which controlled routes from the Black Sea to Persia. Armenian merchants exported furs, timber, honey, and leather, importing luxuries like spices and gems. Feudalism deepened, with peasants (ramiks) tilling lands for noble azats, paying taxes in kind. Cultural revival bloomed: illuminated manuscripts depicted biblical scenes with vibrant miniatures, music filled churches with haunting chants, and literature flourished in classical Armenian.

Yet threats loomed. Byzantine annexations nibbled at borders—Taron in 967, Vaspurakan in 1021 under Emperor Basil II "the Bulgar-Slayer." Internal feuds weakened the realm. By the 11th century, Seljuk Turks under Alp Arslan swept in, capturing Ani in 1064 after a siege that exploited its water supply. Dvin, already a shadow, fell to Seljuks that year, then to Georgians in 1173, Khwarezmians in 1225, and finally Mongols in 1236, who razed it utterly. Excavations since 1937 have unearthed pottery, mosaics, and tools, piecing together this lost world.

The 893 earthquake wasn't just a blip—it reshaped Bagratid Armenia's trajectory, forcing adaptation and innovation. From the ruins rose Ani, symbolizing Armenian endurance amid empires' clashes. This resilience, forged in fire and tremor, offers profound insights for us today. Now, let's pivot to how this ancient cataclysm can turbocharge your modern life. The Armenians didn't just survive; they thrived by embracing change, building stronger, and uniting in adversity. Applying these outcomes personally means viewing life's "earthquakes"—job losses, health scares, or relationship upheavals—as catalysts for growth. Here's how you benefit, with specific ways to integrate this historical wisdom:

- **Cultivate Unbreakable Foundations in Your Daily Routine**: Just as Dvin's rebuilt structures incorporated lessons from the quake, reinforce your life's base. Start by auditing your habits—identify weak spots like poor sleep or procrastination—and shore them up with solid practices, like a 7 AM workout ritual that builds physical and mental stamina, turning potential collapses into sturdy pillars.

- **Embrace Adaptability in Career Shifts**: The shift from Dvin to Ani shows relocation can spark renaissance. If your job feels shaky, proactively scout new opportunities—update your LinkedIn weekly, network at one industry event monthly, and skill-up via online courses in emerging fields like AI, transforming threats into launches for higher achievements.

- **Foster Community Bonds for Emotional Support**: Armenians rallied post-quake, sharing resources and rebuilding together. In your life, nurture a "tribe"—schedule bi-weekly calls with close friends to discuss challenges, join a local hobby group for shared activities, and volunteer quarterly, creating a network that absorbs shocks and amplifies joys.

- **Prioritize Preparedness in Financial Planning**: Dvin's vulnerability exposed the need for defenses. Apply this by building an emergency fund covering six months' expenses, diversifying investments across stocks, bonds, and real estate, and reviewing insurance annually, ensuring life's tremors don't devastate your wallet.

- **Harness Innovation After Setbacks**: Post-893, Armenian architecture evolved with quake-resistant designs. After a personal failure, innovate—journal three lessons learned from a botched project, pivot by testing a new approach within a week, and celebrate small wins, like treating yourself to a favorite meal, to fuel momentum.

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to apply the Dvin earthquake's legacy to your individual life, building resilience like the Bagratids:

Now, let's pivot to how this ancient cataclysm can turbocharge your modern life. The Armenians didn't just survive; they thrived by embracing change, building stronger, and uniting in adversity. Applying these outcomes personally means viewing life's "earthquakes"—job losses, health scares, or relationship upheavals—as catalysts for growth. Here's how you benefit, with specific ways to integrate this historical wisdom:

- **Cultivate Unbreakable Foundations in Your Daily Routine**: Just as Dvin's rebuilt structures incorporated lessons from the quake, reinforce your life's base. Start by auditing your habits—identify weak spots like poor sleep or procrastination—and shore them up with solid practices, like a 7 AM workout ritual that builds physical and mental stamina, turning potential collapses into sturdy pillars.

- **Embrace Adaptability in Career Shifts**: The shift from Dvin to Ani shows relocation can spark renaissance. If your job feels shaky, proactively scout new opportunities—update your LinkedIn weekly, network at one industry event monthly, and skill-up via online courses in emerging fields like AI, transforming threats into launches for higher achievements.

- **Foster Community Bonds for Emotional Support**: Armenians rallied post-quake, sharing resources and rebuilding together. In your life, nurture a "tribe"—schedule bi-weekly calls with close friends to discuss challenges, join a local hobby group for shared activities, and volunteer quarterly, creating a network that absorbs shocks and amplifies joys.

- **Prioritize Preparedness in Financial Planning**: Dvin's vulnerability exposed the need for defenses. Apply this by building an emergency fund covering six months' expenses, diversifying investments across stocks, bonds, and real estate, and reviewing insurance annually, ensuring life's tremors don't devastate your wallet.

- **Harness Innovation After Setbacks**: Post-893, Armenian architecture evolved with quake-resistant designs. After a personal failure, innovate—journal three lessons learned from a botched project, pivot by testing a new approach within a week, and celebrate small wins, like treating yourself to a favorite meal, to fuel momentum.

To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to apply the Dvin earthquake's legacy to your individual life, building resilience like the Bagratids:

**Assess Your Current Landscape (Week 1)**: Spend an evening mapping your life's "fault lines"—list vulnerabilities in health, relationships, career, and finances. Rate each on a 1-10 stability scale, then brainstorm one immediate fix, like booking a doctor's checkup if health scores low.

**Build Defensive Walls (Weeks 2-4)**: Fortify key areas. For career, dedicate 30 minutes daily to learning a new skill via apps like Duolingo or Coursera. In relationships, initiate honest conversations with loved ones about support needs, aiming for deeper connections.

**Simulate Aftershocks and Adapt (Weeks 5-6)**: Role-play scenarios—imagine a job loss and plan responses, like updating your resume or freelancing gigs. Practice flexibility by trying a new routine, such as a different commute or meal prep method, to build adaptability muscles.

**Rebuild and Innovate (Ongoing, Months 1-3)**: Launch a personal "renaissance project"—perhaps a side hustle inspired by Armenian crafts, like starting a blog on history or crafting handmade items. Track progress weekly, adjusting based on feedback, mirroring Ani's rise from Dvin's fall.

**Celebrate Resilience Milestones (Every Quarter)**: Reflect on growth—host a small gathering to share stories of overcoming "tremors," rewarding yourself with experiences like a hiking trip to echo Armenia's mountainous spirit, reinforcing motivation.

By channeling the spirit of 893's survivors, you'll not only weather storms but emerge stronger, more innovative, and deeply connected. History isn't just dusty tomes—it's a blueprint for triumph. Let the midnight tremor of Dvin ignite your unbreakable future.

The Bagratuni dynasty, in particular, rose like a phoenix from the ashes of earlier defeats. Their story begins in the shadows of the 8th century, after the disastrous Battle of Bagrevand in 775, where Arab forces crushed a major Armenian uprising, scattering rival clans and leaving the Bagratunis as one of the few surviving powerhouses. By the 860s, Ashot Bagratuni, a shrewd and ambitious leader, had consolidated control over key territories. He played a delicate diplomatic game, balancing alliances between the Abbasid Caliphate and the resurgent Byzantine Empire to the west. In 862, the Abbasids granted him the title of "prince of princes" (ishkhan ishkhanats), acknowledging his dominance over other Armenian lords. But Ashot dreamed bigger—he wanted a crown. The geopolitical chessboard of the era was a whirlwind of intrigue. The Byzantine Empire, under emperors like Basil I the Macedonian, was reclaiming lost territories and eyeing Armenia as a buffer against Arab incursions. Meanwhile, the Abbasids were weakening, plagued by internal rebellions and the rise of semi-independent emirs in their provinces. Ashot seized the moment. In 884 or 885, Caliph Al-Mu'tamid sent him a royal crown, officially recognizing him as King Ashot I of Armenia. Not to be outdone, Basil I dispatched his own crown, solidifying a Byzantine-Armenian alliance. This dual recognition was a masterstroke, positioning the new Bagratid Kingdom as a sovereign entity caught between two superpowers. Ashot's court moved to Bagaran initially, but Dvin—ancient, strategic, and symbolically potent—loomed as the ultimate prize. Dvin itself was a marvel, a city with roots stretching back millennia. Founded in the 4th century by King Khosrov III Kotak of the Arsacid dynasty, it was built on the ruins of even older settlements dating to the Bronze Age. Perched along the Metsamor River, 35 kilometers south of modern Yerevan, Dvin grew into a fortified stronghold and commercial hub. By the 5th century, it had become the capital of Sassanid Persia’s Armenian province after the fall of the Arsacid kingdom in 428. Persian marzpans (governors) ruled from its palaces, blending Zoroastrian influences with emerging Christian traditions. When the Arabs conquered in 640 during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Constans II, they renamed it Dabil and made it the administrative center of Arminiya, a vast province encompassing Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Under Arab rule, Dvin flourished despite the oppression. Its population swelled to around 100,000 by the 9th century, making it one of the largest cities east of Constantinople. Streets teemed with diversity: Armenian Christians, Arab Muslims, Jews, Persians, and traders from as far as China and India. The economy boomed on the back of the Great Armenian Highway, a vital artery of the Silk Road that funneled goods like textiles, armor, horses, salt, wine, and the prized cochineal dye extracted from insects in nearby Artashat. Artisans crafted exquisite wool and silk fabrics, rugs, pillows, and metalwork that were exported to Byzantine markets and Abbasid courts. Fishing in the Metsamor provided sustenance, while vineyards and orchards dotted the surrounding plains.

Architecturally, Dvin was a testament to Armenian ingenuity. Its defensive walls, reinforced over centuries, encircled a labyrinth of stone buildings. At the heart stood the Cathedral of Saint Grigor, originally a pagan temple converted to Christianity in the 5th century. This massive basilica, measuring over 30 by 58 meters, featured a pentahedral apse, arched galleries, and intricate mosaics—the oldest surviving in Armenia, depicting the Holy Virgin in vibrant tiles. Column capitals bore fern-like reliefs, and cornices were carved with interlaced strands, blending Byzantine, Sassanid, and local styles. Nearby, the catholicos' palace housed the spiritual leader of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a figure as powerful as any king. Zoroastrian fire-temples lingered from Persian days, now overshadowed by churches and monasteries. But Dvin's glory masked vulnerabilities. The region sat atop the volatile collision zone between the Arabian and Eurasian tectonic plates, a hotspot for seismic activity. Earthquakes had rattled the city before—in the mid-9th century, smaller tremors along the Sardarapat-Nakhichevan fault system hinted at brewing disaster. The Parackar-Dvin segment, with its oblique dextral strike-slip motion, was particularly unstable. Historians like Thomas Artsruni and Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi chronicled earlier quakes, but none prepared the inhabitants for what came on that fateful December night in 893. Picture the scene: It's midnight on December 28. The city slumbers under a blanket of stars, perhaps illuminated by a partial lunar eclipse the previous evening, as some Armenian accounts suggest. Families huddle around hearths against the winter chill. In the catholicos' palace, clerics pore over illuminated manuscripts. Merchants count their dinars in dimly lit warehouses. Suddenly, a low rumble builds to a deafening roar. The ground heaves like a living beast, cracking open fissures that swallow streets whole. Buildings sway and collapse in cascades of stone and timber. The Cathedral of Saint Grigor, that architectural jewel, crumbles—its dome crashing down, mosaics shattering into dust. Defensive walls, meant to repel armies, buckle like paper. Landslides thunder down from the Artashat Plateau, burying villages and retreats. Bishop Grigor of Rshtunik, seeking solace in a mountain hermitage, perishes along with his entourage as rocks rain from above.

The quake's magnitude is debated—estimates range from 5.3 to 7.0 or higher, with a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent) to X (Extreme). It struck near coordinates 40°00′N 44°36′E, epicentered close to Dvin. Aftershocks ravaged the area for five harrowing days, compounding the terror. Casualty figures vary wildly in contemporary sources: Armenian chroniclers like Stepanos Taronetsi report 30,000 dead, while Arabic historians inflate it to 70,000, 150,000, or even 180,000. Modern scholars settle around 20,000 to 30,000, a staggering toll for the era. Most of Dvin's 100,000 residents were affected—only about 100 houses remained standing. Palaces, churches, markets, all lay in ruins. The Metsamor River may have flooded from disrupted banks, adding to the chaos. Confusion in historical records adds layers of intrigue. Arabic sources called the city Dabil, leading later catalogers to misattribute the quake to Ardabil in Iran, creating a "phantom" event there. Dates fluctuate too—some say March 23 or December 24, years from 893 to 895. Armenian writers linked it to celestial omens, like the eclipse, viewing it as divine wrath. But the impact was undeniable. Dvin's defenses were obliterated, leaving it vulnerable to opportunists. Enter the political fallout, a drama worthy of any epic saga. At the time, Smbat I Bagratuni had just been crowned king in 892, having recaptured Dvin from Arab control that same year. The earthquake stripped away his hard-won gains. With walls down and the population decimated, Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Saj, the Sajid emir of Adharbayjan (modern Azerbaijan), swooped in. The Sajids, a Persianized Turkish dynasty ruling as Abbasid governors, saw Dvin as a strategic base. Muhammad captured the city without resistance, converting it into a military outpost and imposing tribute. This humiliation stung the Bagratids, but Smbat focused on consolidation elsewhere. The quake accelerated Dvin's decline, though it wasn't immediate. Survivors rebuilt amid the rubble, and by the 10th century, the city regained some prosperity under Bagratid oversight. Trade resumed, artisans returned, and new structures rose from the ashes. However, repeated invasions eroded its status. In 901, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj (Muhammad's brother) launched campaigns against Smbat, culminating in the king's capture, torture, and execution in 914—a grisly affair where Smbat was crucified and beheaded. His son, Ashot II "the Iron," fought back with Byzantine aid, reclaiming territories and earning the title Shahanshah (king of kings) in 919.

Under subsequent rulers like Abas I (928–953) and Ashot III "the Merciful" (953–977), the kingdom entered a golden age. Ashot III relocated the capital to Ani in 961, a move perhaps influenced by Dvin's seismic scars. Ani, perched on a triangular plateau overlooking the Akhuryan River, became a fortified wonder—dubbed the "City of 1,001 Churches" with its soaring cathedrals, massive walls, and bustling markets. Architects like Trdat designed masterpieces blending Armenian, Byzantine, and Islamic elements: domed basilicas with frescoes, vaulted halls, and intricate carvings. Monasteries such as Sanahin and Haghpat, founded by Ashot III's queen Khosrovanush, became intellectual hubs, producing philosophers like Grigor Narekatsi, whose mystical poetry still inspires. Economically, the post-quake era saw diversification. With Dvin diminished, trade shifted north to Ani, which controlled routes from the Black Sea to Persia. Armenian merchants exported furs, timber, honey, and leather, importing luxuries like spices and gems. Feudalism deepened, with peasants (ramiks) tilling lands for noble azats, paying taxes in kind. Cultural revival bloomed: illuminated manuscripts depicted biblical scenes with vibrant miniatures, music filled churches with haunting chants, and literature flourished in classical Armenian. Yet threats loomed. Byzantine annexations nibbled at borders—Taron in 967, Vaspurakan in 1021 under Emperor Basil II "the Bulgar-Slayer." Internal feuds weakened the realm. By the 11th century, Seljuk Turks under Alp Arslan swept in, capturing Ani in 1064 after a siege that exploited its water supply. Dvin, already a shadow, fell to Seljuks that year, then to Georgians in 1173, Khwarezmians in 1225, and finally Mongols in 1236, who razed it utterly. Excavations since 1937 have unearthed pottery, mosaics, and tools, piecing together this lost world. The 893 earthquake wasn't just a blip—it reshaped Bagratid Armenia's trajectory, forcing adaptation and innovation. From the ruins rose Ani, symbolizing Armenian endurance amid empires' clashes. This resilience, forged in fire and tremor, offers profound insights for us today.

Now, let's pivot to how this ancient cataclysm can turbocharge your modern life. The Armenians didn't just survive; they thrived by embracing change, building stronger, and uniting in adversity. Applying these outcomes personally means viewing life's "earthquakes"—job losses, health scares, or relationship upheavals—as catalysts for growth. Here's how you benefit, with specific ways to integrate this historical wisdom: - **Cultivate Unbreakable Foundations in Your Daily Routine**: Just as Dvin's rebuilt structures incorporated lessons from the quake, reinforce your life's base. Start by auditing your habits—identify weak spots like poor sleep or procrastination—and shore them up with solid practices, like a 7 AM workout ritual that builds physical and mental stamina, turning potential collapses into sturdy pillars. - **Embrace Adaptability in Career Shifts**: The shift from Dvin to Ani shows relocation can spark renaissance. If your job feels shaky, proactively scout new opportunities—update your LinkedIn weekly, network at one industry event monthly, and skill-up via online courses in emerging fields like AI, transforming threats into launches for higher achievements. - **Foster Community Bonds for Emotional Support**: Armenians rallied post-quake, sharing resources and rebuilding together. In your life, nurture a "tribe"—schedule bi-weekly calls with close friends to discuss challenges, join a local hobby group for shared activities, and volunteer quarterly, creating a network that absorbs shocks and amplifies joys. - **Prioritize Preparedness in Financial Planning**: Dvin's vulnerability exposed the need for defenses. Apply this by building an emergency fund covering six months' expenses, diversifying investments across stocks, bonds, and real estate, and reviewing insurance annually, ensuring life's tremors don't devastate your wallet. - **Harness Innovation After Setbacks**: Post-893, Armenian architecture evolved with quake-resistant designs. After a personal failure, innovate—journal three lessons learned from a botched project, pivot by testing a new approach within a week, and celebrate small wins, like treating yourself to a favorite meal, to fuel momentum. To make this actionable, here's a step-by-step plan to apply the Dvin earthquake's legacy to your individual life, building resilience like the Bagratids: