Imagine a frigid winter day in the year 880, where the snow-dusted plains of ancient China buzz with the thunder of marching feet and the clash of desperate ambitions. On December 22, in the heart of the Tang dynasty's eastern capital, Luoyang, a rebel force led by the indomitable Huang Chao breached the city's formidable walls, marking a pivotal turning point in one of history's most chaotic uprisings. This wasn't just a skirmish; it was the culmination of years of simmering discontent that would accelerate the crumble of a once-glorious empire. While the Tang dynasty had ruled China for over two centuries, boasting cultural splendor and territorial vastness, by the late 9th century, it was a hollow shell riddled with corruption, famine, and military ineptitude. Huang Chao, a failed scholar turned salt smuggler turned revolutionary, embodied the fury of the oppressed masses. His capture of Luoyang on that fateful day wasn't merely a military victory—it was a symbol of how systemic failures can ignite cataclysmic change.

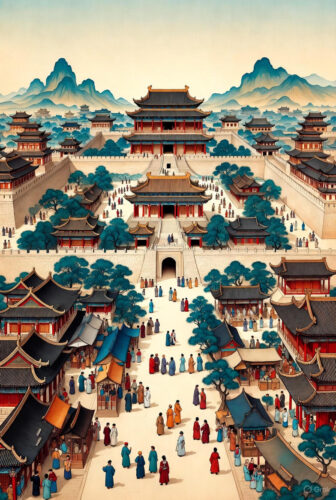

To truly appreciate the significance of this event, we must delve deep into the historical tapestry of the Tang dynasty, its golden peaks, and its tragic descent. The Tang era, spanning from 618 to 907 AD, is often hailed as one of China's most prosperous periods, a time when poetry flourished under luminaries like Li Bai and Du Fu, trade routes like the Silk Road thrived, and innovations in printing, gunpowder, and porcelain advanced civilization. Founded by Li Yuan after the collapse of the Sui dynasty, the Tang expanded China's borders to unprecedented extents, incorporating influences from Central Asia, Persia, and even India. Emperors like Taizong (r. 626–649) and Xuanzong (r. 712–756) presided over a cosmopolitan court where Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism intermingled, fostering an artistic renaissance. Cities like Chang'an, the western capital, became the world's largest metropolis, home to over a million souls, with grand palaces, bustling markets, and foreign envoys bearing exotic tributes. Yet, beneath this veneer of grandeur lurked seeds of decay. The An Lushan Rebellion of 755–763 was the first major blow. An Lushan, a general of Sogdian-Turkic descent, rebelled against Emperor Xuanzong, capturing Chang'an and forcing the emperor to flee. The rebellion, fueled by ethnic tensions and power struggles among the military governors (jiedushi), devastated the empire. Millions perished from warfare, famine, and disease, and the central government's control weakened as regional warlords gained autonomy. Although the Tang quelled the uprising with help from Uyghur allies, the dynasty never fully recovered. The imperial court became increasingly reliant on eunuchs for administration, leading to factional infighting, while heavy taxation to fund military campaigns burdened peasants and landowners alike. By the mid-9th century, climate shifts brought droughts and floods, exacerbating famines that left swaths of the population starving. Salt monopolies, intended to generate revenue, instead spawned widespread smuggling, creating a shadow economy ripe for exploitation.

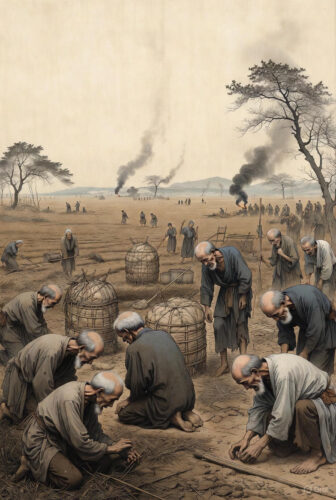

Yet, beneath this veneer of grandeur lurked seeds of decay. The An Lushan Rebellion of 755–763 was the first major blow. An Lushan, a general of Sogdian-Turkic descent, rebelled against Emperor Xuanzong, capturing Chang'an and forcing the emperor to flee. The rebellion, fueled by ethnic tensions and power struggles among the military governors (jiedushi), devastated the empire. Millions perished from warfare, famine, and disease, and the central government's control weakened as regional warlords gained autonomy. Although the Tang quelled the uprising with help from Uyghur allies, the dynasty never fully recovered. The imperial court became increasingly reliant on eunuchs for administration, leading to factional infighting, while heavy taxation to fund military campaigns burdened peasants and landowners alike. By the mid-9th century, climate shifts brought droughts and floods, exacerbating famines that left swaths of the population starving. Salt monopolies, intended to generate revenue, instead spawned widespread smuggling, creating a shadow economy ripe for exploitation. Enter Huang Chao, born in 835 AD in Yuanqu (modern-day Cao County, Shandong province), into a family of affluent salt smugglers. The salt trade was a lucrative but illicit enterprise, as the government tightly controlled it since the An Lushan era to finance defenses. Huang's clan amassed wealth by evading taxes and bribing officials, giving young Huang a taste of the system's hypocrisies. He was no mere thug; educated in the classics, he excelled in swordsmanship, archery, and rhetoric. Like many ambitious youths, he aspired to the imperial examinations, the gateway to officialdom in Confucian China. These grueling tests, held in the capital, assessed knowledge of poetry, history, and philosophy, promising social mobility to the talented. Huang sat for them multiple times but failed—whether due to bias, corruption, or sheer competition remains debated. His bitterness grew; in one apocryphal tale, he composed a poem lamenting the exams' unfairness, foreshadowing his rebellious path. "The chrysanthemums bloom in autumn, but the examiner's pen withers my dreams," he allegedly wrote, capturing the frustration of countless failed scholars.

By the 870s, discontent boiled over into open revolt. Small-scale uprisings dotted the landscape, driven by impoverished farmers, displaced soldiers, and merchants chafing under taxes. In 874, Wang Xianzhi, a fellow salt trader from Puzhou (modern-day Puyang, Henan), ignited a major rebellion in Shandong. Wang's forces, numbering in the thousands, raided granaries and attacked local officials, proclaiming slogans like "Equalize the land" to appeal to peasants. Huang Chao, leveraging his family's networks, joined Wang in 875, bringing recruits and resources. Together, they formed a formidable alliance, with Huang's tactical acumen complementing Wang's charisma. Their army swelled to tens of thousands, a motley crew of peasants, bandits, and defected soldiers armed with spears, bows, and improvised weapons. They adopted guerrilla tactics, striking swiftly and vanishing into the countryside, evading the Tang's cumbersome armies.

Tensions arose, however. Wang favored negotiating with the Tang for amnesty and titles, while Huang advocated total overthrow. In 878, they split, with Huang taking 20,000 men southward. This decision proved prescient; Wang was defeated and killed later that year by Tang general Zeng Yuanyu. Huang, meanwhile, rampaged through southern China, capturing key cities like Guangzhou (Canton) in 879. Guangzhou, a vital port for Arab and Persian trade, was sacked brutally—historical accounts claim Huang's forces massacred thousands of foreign merchants, though numbers vary wildly from 120,000 in Arab sources to more modest figures in Chinese records. This atrocity, while horrific, replenished his coffers with spices, silks, and gold, allowing him to equip his army better. Diseases like malaria decimated his ranks in the humid south, claiming up to 40% of his troops, but Huang pressed on, turning north with renewed vigor.

The Tang court, under Emperor Xizong (r. 873–888), a young puppet manipulated by eunuchs like Tian Lingzi, underestimated the threat. Xizong, more interested in polo and cockfighting than governance, squandered resources on luxuries while famine ravaged the land. Military governors, now semi-independent, often ignored imperial commands, focusing on personal power. In spring 880, Huang's forces crossed the Yangtze River, defeating Tang defenders at key passes. He bribed some generals, like Zhang Lin of E Prefecture, only to betray and kill them later. By autumn, his army, now 150,000 strong, marched on the twin capitals: Luoyang in the east and Chang'an in the west.

Enter Huang Chao, born in 835 AD in Yuanqu (modern-day Cao County, Shandong province), into a family of affluent salt smugglers. The salt trade was a lucrative but illicit enterprise, as the government tightly controlled it since the An Lushan era to finance defenses. Huang's clan amassed wealth by evading taxes and bribing officials, giving young Huang a taste of the system's hypocrisies. He was no mere thug; educated in the classics, he excelled in swordsmanship, archery, and rhetoric. Like many ambitious youths, he aspired to the imperial examinations, the gateway to officialdom in Confucian China. These grueling tests, held in the capital, assessed knowledge of poetry, history, and philosophy, promising social mobility to the talented. Huang sat for them multiple times but failed—whether due to bias, corruption, or sheer competition remains debated. His bitterness grew; in one apocryphal tale, he composed a poem lamenting the exams' unfairness, foreshadowing his rebellious path. "The chrysanthemums bloom in autumn, but the examiner's pen withers my dreams," he allegedly wrote, capturing the frustration of countless failed scholars.

By the 870s, discontent boiled over into open revolt. Small-scale uprisings dotted the landscape, driven by impoverished farmers, displaced soldiers, and merchants chafing under taxes. In 874, Wang Xianzhi, a fellow salt trader from Puzhou (modern-day Puyang, Henan), ignited a major rebellion in Shandong. Wang's forces, numbering in the thousands, raided granaries and attacked local officials, proclaiming slogans like "Equalize the land" to appeal to peasants. Huang Chao, leveraging his family's networks, joined Wang in 875, bringing recruits and resources. Together, they formed a formidable alliance, with Huang's tactical acumen complementing Wang's charisma. Their army swelled to tens of thousands, a motley crew of peasants, bandits, and defected soldiers armed with spears, bows, and improvised weapons. They adopted guerrilla tactics, striking swiftly and vanishing into the countryside, evading the Tang's cumbersome armies.

Tensions arose, however. Wang favored negotiating with the Tang for amnesty and titles, while Huang advocated total overthrow. In 878, they split, with Huang taking 20,000 men southward. This decision proved prescient; Wang was defeated and killed later that year by Tang general Zeng Yuanyu. Huang, meanwhile, rampaged through southern China, capturing key cities like Guangzhou (Canton) in 879. Guangzhou, a vital port for Arab and Persian trade, was sacked brutally—historical accounts claim Huang's forces massacred thousands of foreign merchants, though numbers vary wildly from 120,000 in Arab sources to more modest figures in Chinese records. This atrocity, while horrific, replenished his coffers with spices, silks, and gold, allowing him to equip his army better. Diseases like malaria decimated his ranks in the humid south, claiming up to 40% of his troops, but Huang pressed on, turning north with renewed vigor.

The Tang court, under Emperor Xizong (r. 873–888), a young puppet manipulated by eunuchs like Tian Lingzi, underestimated the threat. Xizong, more interested in polo and cockfighting than governance, squandered resources on luxuries while famine ravaged the land. Military governors, now semi-independent, often ignored imperial commands, focusing on personal power. In spring 880, Huang's forces crossed the Yangtze River, defeating Tang defenders at key passes. He bribed some generals, like Zhang Lin of E Prefecture, only to betray and kill them later. By autumn, his army, now 150,000 strong, marched on the twin capitals: Luoyang in the east and Chang'an in the west. Luoyang, once the Sui and early Tang capital, remained a symbolic and strategic hub by 880. Rebuilt after earlier destructions, it housed imperial tombs, granaries, and a secondary court. Its walls, fortified with moats and towers, were guarded by the Shence Army, an elite but demoralized force. Huang's approach terrified the populace; rumors of his brutality preceded him. On December 22, 880, after a brief siege, Huang's rebels overwhelmed the defenses. Accounts describe chaotic street fighting, with archers raining arrows from rooftops and infantry breaching gates with battering rams. The city's governor fled, and Huang's men poured in, looting palaces and executing resistant officials. This capture was a masterstroke—it severed supply lines to Chang'an and boosted rebel morale, proving the Tang's invincibility was a myth. Huang proclaimed amnesty for submissive lower officials, integrating some into his administration to maintain order, a nod to his scholarly roots.

Emboldened, Huang advanced on Chang'an. The emperor dispatched Qi Kerang with the Shence Army, but they were routed in a humiliating defeat. Xizong fled to Chengdu in Sichuan, disguised as a commoner, his entourage scrambling over mountain passes in blizzards. On January 16, 881, Huang entered Chang'an triumphantly, declaring himself Emperor of the Great Qi dynasty with the era name Wangba ("King's Hegemony"). He installed his wife, Lady Cao, as empress and appointed loyalists like Shang Rang and Zhao Zhang as chancellors. For a brief period, Huang attempted reforms: reducing taxes, redistributing land, and punishing corrupt Tang holdouts. Yet, his rule was marred by paranoia and violence; mass executions of aristocrats and scholars alienated potential allies. The city, already strained, suffered from food shortages as Tang loyalists blockaded supplies.

The Tang counteroffensive gathered steam. Xizong, from exile, rallied warlords like Li Keyong, a Shatuo Turk chieftain, and Wang Chongrong. In 882, alliances formed, and by spring 883, Li Keyong's forces, bolstered by Uyghur cavalry, besieged Chang'an. Huang's army, weakened by desertions and infighting, crumbled. A massive battle saw 150,000 Qi troops decimated; Huang fled east, abandoning the capital to looting Tang soldiers. Chang'an, once a jewel, was reduced to rubble—palaces burned, markets emptied.

Luoyang, once the Sui and early Tang capital, remained a symbolic and strategic hub by 880. Rebuilt after earlier destructions, it housed imperial tombs, granaries, and a secondary court. Its walls, fortified with moats and towers, were guarded by the Shence Army, an elite but demoralized force. Huang's approach terrified the populace; rumors of his brutality preceded him. On December 22, 880, after a brief siege, Huang's rebels overwhelmed the defenses. Accounts describe chaotic street fighting, with archers raining arrows from rooftops and infantry breaching gates with battering rams. The city's governor fled, and Huang's men poured in, looting palaces and executing resistant officials. This capture was a masterstroke—it severed supply lines to Chang'an and boosted rebel morale, proving the Tang's invincibility was a myth. Huang proclaimed amnesty for submissive lower officials, integrating some into his administration to maintain order, a nod to his scholarly roots.

Emboldened, Huang advanced on Chang'an. The emperor dispatched Qi Kerang with the Shence Army, but they were routed in a humiliating defeat. Xizong fled to Chengdu in Sichuan, disguised as a commoner, his entourage scrambling over mountain passes in blizzards. On January 16, 881, Huang entered Chang'an triumphantly, declaring himself Emperor of the Great Qi dynasty with the era name Wangba ("King's Hegemony"). He installed his wife, Lady Cao, as empress and appointed loyalists like Shang Rang and Zhao Zhang as chancellors. For a brief period, Huang attempted reforms: reducing taxes, redistributing land, and punishing corrupt Tang holdouts. Yet, his rule was marred by paranoia and violence; mass executions of aristocrats and scholars alienated potential allies. The city, already strained, suffered from food shortages as Tang loyalists blockaded supplies.

The Tang counteroffensive gathered steam. Xizong, from exile, rallied warlords like Li Keyong, a Shatuo Turk chieftain, and Wang Chongrong. In 882, alliances formed, and by spring 883, Li Keyong's forces, bolstered by Uyghur cavalry, besieged Chang'an. Huang's army, weakened by desertions and infighting, crumbled. A massive battle saw 150,000 Qi troops decimated; Huang fled east, abandoning the capital to looting Tang soldiers. Chang'an, once a jewel, was reduced to rubble—palaces burned, markets emptied. Huang's odyssey continued through 883–884, a desperate flight across Henan and Shandong. He captured Cai Prefecture, but betrayals mounted. At Chen Prefecture, a siege failed, and crossing the Yellow River, floods and ambushes whittled his forces to mere thousands. In summer 884, near Yan Prefecture, Tang general Shi Pu's troops encircled him. On July 13, 884, in Langhu Valley, Huang met his end. Accounts vary: some say he committed suicide, instructing his nephew Lin Yan to surrender with his head; others claim Lin beheaded him in a bid for mercy. Lin was slain en route, and Huang's severed head was paraded as a trophy. His brothers and family perished similarly, ending the Qi interlude.

Huang's odyssey continued through 883–884, a desperate flight across Henan and Shandong. He captured Cai Prefecture, but betrayals mounted. At Chen Prefecture, a siege failed, and crossing the Yellow River, floods and ambushes whittled his forces to mere thousands. In summer 884, near Yan Prefecture, Tang general Shi Pu's troops encircled him. On July 13, 884, in Langhu Valley, Huang met his end. Accounts vary: some say he committed suicide, instructing his nephew Lin Yan to surrender with his head; others claim Lin beheaded him in a bid for mercy. Lin was slain en route, and Huang's severed head was paraded as a trophy. His brothers and family perished similarly, ending the Qi interlude. The rebellion's toll was staggering: estimates suggest millions dead, economies shattered, and the Tang irreparably weakened. By 907, Zhu Wen, a former rebel turned Tang general, usurped the throne, founding the Later Liang and ushering in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period—a fragmented era of warlordism lasting until the Song unification in 960. Huang Chao's uprising exposed the Tang's vulnerabilities: overreliance on regional governors, eunuch interference, and neglect of peasant woes. It also highlighted themes of social mobility; Huang, a commoner, nearly toppled an empire, inspiring later folklore. In popular tales, he became a Robin Hood figure, though historical records paint him as ruthless—accused of cannibalism during sieges, a charge possibly exaggerated by victors.

Culturally, the rebellion accelerated shifts. Buddhism, already declining after Emperor Wuzong's persecutions in the 840s, suffered further as monasteries were looted. Neo-Confucianism would later rise in response to such chaos. Economically, the destruction of Chang'an shifted power eastward, paving the way for Kaifeng as a future capital. Militarily, the rise of Shatuo Turks like Li Keyong foreshadowed non-Han influences in subsequent dynasties.

While Huang Chao's story is one of ambition and ruin, it's packed with intriguing what-ifs. What if he had passed those exams? Might he have reformed the system from within? Or if the Tang had negotiated earlier? The capture of Luoyang stands as a fulcrum, a moment when a smuggler's son humbled an empire, reminding us that history often pivots on the audacity of the overlooked.

Shifting from the annals of the past to the pulse of the present, the saga of Huang Chao's rebellion offers profound insights for personal growth. At its core, this historical fact underscores the power of challenging entrenched systems—whether imperial corruption or self-imposed limitations. By applying the outcomes of this event, individuals can harness the spirit of transformation to overhaul stagnant aspects of their lives, fostering resilience and proactive change. Here's how this ancient upheaval can motivate you today:

- **Recognize and Confront Personal 'Corruptions'**: Just as Tang excesses fueled rebellion, identify toxic habits like procrastination or negative self-talk that erode your potential. Audit your daily routines to pinpoint drains on your energy, much like Huang spotted governmental weaknesses.

- **Build Alliances for Strength**: Huang's army grew through recruitment; similarly, surround yourself with supportive networks. Seek mentors or accountability partners to amplify your efforts in pursuing goals, turning solo struggles into collective triumphs.

- **Embrace Failure as Fuel**: Huang's exam flops propelled him forward—use setbacks, like job rejections or fitness plateaus, as catalysts. Reframe them as training for greater pursuits, building mental fortitude.

- **Strategize Bold Moves**: The capture of Luoyang required calculated risks; map out ambitious steps in your career or health journeys, breaking them into sieges on smaller objectives for momentum.

- **Sustain Momentum Amid Adversity**: Despite losses in the south, Huang pivoted north—cultivate adaptability by setting contingency plans, ensuring temporary defeats don't derail long-term visions.

To integrate these lessons into a concrete plan, follow this step-by-step blueprint for personal rebellion against complacency:

The rebellion's toll was staggering: estimates suggest millions dead, economies shattered, and the Tang irreparably weakened. By 907, Zhu Wen, a former rebel turned Tang general, usurped the throne, founding the Later Liang and ushering in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period—a fragmented era of warlordism lasting until the Song unification in 960. Huang Chao's uprising exposed the Tang's vulnerabilities: overreliance on regional governors, eunuch interference, and neglect of peasant woes. It also highlighted themes of social mobility; Huang, a commoner, nearly toppled an empire, inspiring later folklore. In popular tales, he became a Robin Hood figure, though historical records paint him as ruthless—accused of cannibalism during sieges, a charge possibly exaggerated by victors.

Culturally, the rebellion accelerated shifts. Buddhism, already declining after Emperor Wuzong's persecutions in the 840s, suffered further as monasteries were looted. Neo-Confucianism would later rise in response to such chaos. Economically, the destruction of Chang'an shifted power eastward, paving the way for Kaifeng as a future capital. Militarily, the rise of Shatuo Turks like Li Keyong foreshadowed non-Han influences in subsequent dynasties.

While Huang Chao's story is one of ambition and ruin, it's packed with intriguing what-ifs. What if he had passed those exams? Might he have reformed the system from within? Or if the Tang had negotiated earlier? The capture of Luoyang stands as a fulcrum, a moment when a smuggler's son humbled an empire, reminding us that history often pivots on the audacity of the overlooked.

Shifting from the annals of the past to the pulse of the present, the saga of Huang Chao's rebellion offers profound insights for personal growth. At its core, this historical fact underscores the power of challenging entrenched systems—whether imperial corruption or self-imposed limitations. By applying the outcomes of this event, individuals can harness the spirit of transformation to overhaul stagnant aspects of their lives, fostering resilience and proactive change. Here's how this ancient upheaval can motivate you today:

- **Recognize and Confront Personal 'Corruptions'**: Just as Tang excesses fueled rebellion, identify toxic habits like procrastination or negative self-talk that erode your potential. Audit your daily routines to pinpoint drains on your energy, much like Huang spotted governmental weaknesses.

- **Build Alliances for Strength**: Huang's army grew through recruitment; similarly, surround yourself with supportive networks. Seek mentors or accountability partners to amplify your efforts in pursuing goals, turning solo struggles into collective triumphs.

- **Embrace Failure as Fuel**: Huang's exam flops propelled him forward—use setbacks, like job rejections or fitness plateaus, as catalysts. Reframe them as training for greater pursuits, building mental fortitude.

- **Strategize Bold Moves**: The capture of Luoyang required calculated risks; map out ambitious steps in your career or health journeys, breaking them into sieges on smaller objectives for momentum.

- **Sustain Momentum Amid Adversity**: Despite losses in the south, Huang pivoted north—cultivate adaptability by setting contingency plans, ensuring temporary defeats don't derail long-term visions.

To integrate these lessons into a concrete plan, follow this step-by-step blueprint for personal rebellion against complacency:

**Assess Your Empire (Week 1)**: Dedicate time to journaling: List three 'dynasties' in your life needing reform, such as work-life balance, financial habits, or relationships. Detail specific grievances, echoing the Tang peasants' complaints.

**Gather Your Forces (Weeks 2-3)**: Research resources—books, apps, or courses—on your chosen areas. Connect with one new ally weekly, perhaps joining online communities or scheduling coffee chats, to build a support 'army'.

**Launch the Assault (Weeks 4-6)**: Target one area with daily actions, like 30 minutes of exercise to conquer health inertia. Track progress in a log, celebrating small victories as Huang did with captured cities.

**Adapt and Consolidate (Ongoing)**: Monthly reviews: Adjust tactics if obstacles arise, incorporating feedback. Reward sustained efforts, like a treat after milestones, to maintain morale.

**Reign Victoriously (Long-Term)**: Once reformed, establish new 'laws'—habits like weekly reflections—to prevent backsliding. Share your story to inspire others, perpetuating the cycle of positive change.

By channeling Huang Chao's defiant energy, you transform historical echoes into personal empowerment, proving that even empires fall to determined resolve. Let's make history in our own lives!

Yet, beneath this veneer of grandeur lurked seeds of decay. The An Lushan Rebellion of 755–763 was the first major blow. An Lushan, a general of Sogdian-Turkic descent, rebelled against Emperor Xuanzong, capturing Chang'an and forcing the emperor to flee. The rebellion, fueled by ethnic tensions and power struggles among the military governors (jiedushi), devastated the empire. Millions perished from warfare, famine, and disease, and the central government's control weakened as regional warlords gained autonomy. Although the Tang quelled the uprising with help from Uyghur allies, the dynasty never fully recovered. The imperial court became increasingly reliant on eunuchs for administration, leading to factional infighting, while heavy taxation to fund military campaigns burdened peasants and landowners alike. By the mid-9th century, climate shifts brought droughts and floods, exacerbating famines that left swaths of the population starving. Salt monopolies, intended to generate revenue, instead spawned widespread smuggling, creating a shadow economy ripe for exploitation.

Enter Huang Chao, born in 835 AD in Yuanqu (modern-day Cao County, Shandong province), into a family of affluent salt smugglers. The salt trade was a lucrative but illicit enterprise, as the government tightly controlled it since the An Lushan era to finance defenses. Huang's clan amassed wealth by evading taxes and bribing officials, giving young Huang a taste of the system's hypocrisies. He was no mere thug; educated in the classics, he excelled in swordsmanship, archery, and rhetoric. Like many ambitious youths, he aspired to the imperial examinations, the gateway to officialdom in Confucian China. These grueling tests, held in the capital, assessed knowledge of poetry, history, and philosophy, promising social mobility to the talented. Huang sat for them multiple times but failed—whether due to bias, corruption, or sheer competition remains debated. His bitterness grew; in one apocryphal tale, he composed a poem lamenting the exams' unfairness, foreshadowing his rebellious path. "The chrysanthemums bloom in autumn, but the examiner's pen withers my dreams," he allegedly wrote, capturing the frustration of countless failed scholars. By the 870s, discontent boiled over into open revolt. Small-scale uprisings dotted the landscape, driven by impoverished farmers, displaced soldiers, and merchants chafing under taxes. In 874, Wang Xianzhi, a fellow salt trader from Puzhou (modern-day Puyang, Henan), ignited a major rebellion in Shandong. Wang's forces, numbering in the thousands, raided granaries and attacked local officials, proclaiming slogans like "Equalize the land" to appeal to peasants. Huang Chao, leveraging his family's networks, joined Wang in 875, bringing recruits and resources. Together, they formed a formidable alliance, with Huang's tactical acumen complementing Wang's charisma. Their army swelled to tens of thousands, a motley crew of peasants, bandits, and defected soldiers armed with spears, bows, and improvised weapons. They adopted guerrilla tactics, striking swiftly and vanishing into the countryside, evading the Tang's cumbersome armies. Tensions arose, however. Wang favored negotiating with the Tang for amnesty and titles, while Huang advocated total overthrow. In 878, they split, with Huang taking 20,000 men southward. This decision proved prescient; Wang was defeated and killed later that year by Tang general Zeng Yuanyu. Huang, meanwhile, rampaged through southern China, capturing key cities like Guangzhou (Canton) in 879. Guangzhou, a vital port for Arab and Persian trade, was sacked brutally—historical accounts claim Huang's forces massacred thousands of foreign merchants, though numbers vary wildly from 120,000 in Arab sources to more modest figures in Chinese records. This atrocity, while horrific, replenished his coffers with spices, silks, and gold, allowing him to equip his army better. Diseases like malaria decimated his ranks in the humid south, claiming up to 40% of his troops, but Huang pressed on, turning north with renewed vigor. The Tang court, under Emperor Xizong (r. 873–888), a young puppet manipulated by eunuchs like Tian Lingzi, underestimated the threat. Xizong, more interested in polo and cockfighting than governance, squandered resources on luxuries while famine ravaged the land. Military governors, now semi-independent, often ignored imperial commands, focusing on personal power. In spring 880, Huang's forces crossed the Yangtze River, defeating Tang defenders at key passes. He bribed some generals, like Zhang Lin of E Prefecture, only to betray and kill them later. By autumn, his army, now 150,000 strong, marched on the twin capitals: Luoyang in the east and Chang'an in the west.

Luoyang, once the Sui and early Tang capital, remained a symbolic and strategic hub by 880. Rebuilt after earlier destructions, it housed imperial tombs, granaries, and a secondary court. Its walls, fortified with moats and towers, were guarded by the Shence Army, an elite but demoralized force. Huang's approach terrified the populace; rumors of his brutality preceded him. On December 22, 880, after a brief siege, Huang's rebels overwhelmed the defenses. Accounts describe chaotic street fighting, with archers raining arrows from rooftops and infantry breaching gates with battering rams. The city's governor fled, and Huang's men poured in, looting palaces and executing resistant officials. This capture was a masterstroke—it severed supply lines to Chang'an and boosted rebel morale, proving the Tang's invincibility was a myth. Huang proclaimed amnesty for submissive lower officials, integrating some into his administration to maintain order, a nod to his scholarly roots. Emboldened, Huang advanced on Chang'an. The emperor dispatched Qi Kerang with the Shence Army, but they were routed in a humiliating defeat. Xizong fled to Chengdu in Sichuan, disguised as a commoner, his entourage scrambling over mountain passes in blizzards. On January 16, 881, Huang entered Chang'an triumphantly, declaring himself Emperor of the Great Qi dynasty with the era name Wangba ("King's Hegemony"). He installed his wife, Lady Cao, as empress and appointed loyalists like Shang Rang and Zhao Zhang as chancellors. For a brief period, Huang attempted reforms: reducing taxes, redistributing land, and punishing corrupt Tang holdouts. Yet, his rule was marred by paranoia and violence; mass executions of aristocrats and scholars alienated potential allies. The city, already strained, suffered from food shortages as Tang loyalists blockaded supplies. The Tang counteroffensive gathered steam. Xizong, from exile, rallied warlords like Li Keyong, a Shatuo Turk chieftain, and Wang Chongrong. In 882, alliances formed, and by spring 883, Li Keyong's forces, bolstered by Uyghur cavalry, besieged Chang'an. Huang's army, weakened by desertions and infighting, crumbled. A massive battle saw 150,000 Qi troops decimated; Huang fled east, abandoning the capital to looting Tang soldiers. Chang'an, once a jewel, was reduced to rubble—palaces burned, markets emptied.

Huang's odyssey continued through 883–884, a desperate flight across Henan and Shandong. He captured Cai Prefecture, but betrayals mounted. At Chen Prefecture, a siege failed, and crossing the Yellow River, floods and ambushes whittled his forces to mere thousands. In summer 884, near Yan Prefecture, Tang general Shi Pu's troops encircled him. On July 13, 884, in Langhu Valley, Huang met his end. Accounts vary: some say he committed suicide, instructing his nephew Lin Yan to surrender with his head; others claim Lin beheaded him in a bid for mercy. Lin was slain en route, and Huang's severed head was paraded as a trophy. His brothers and family perished similarly, ending the Qi interlude.

The rebellion's toll was staggering: estimates suggest millions dead, economies shattered, and the Tang irreparably weakened. By 907, Zhu Wen, a former rebel turned Tang general, usurped the throne, founding the Later Liang and ushering in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period—a fragmented era of warlordism lasting until the Song unification in 960. Huang Chao's uprising exposed the Tang's vulnerabilities: overreliance on regional governors, eunuch interference, and neglect of peasant woes. It also highlighted themes of social mobility; Huang, a commoner, nearly toppled an empire, inspiring later folklore. In popular tales, he became a Robin Hood figure, though historical records paint him as ruthless—accused of cannibalism during sieges, a charge possibly exaggerated by victors. Culturally, the rebellion accelerated shifts. Buddhism, already declining after Emperor Wuzong's persecutions in the 840s, suffered further as monasteries were looted. Neo-Confucianism would later rise in response to such chaos. Economically, the destruction of Chang'an shifted power eastward, paving the way for Kaifeng as a future capital. Militarily, the rise of Shatuo Turks like Li Keyong foreshadowed non-Han influences in subsequent dynasties. While Huang Chao's story is one of ambition and ruin, it's packed with intriguing what-ifs. What if he had passed those exams? Might he have reformed the system from within? Or if the Tang had negotiated earlier? The capture of Luoyang stands as a fulcrum, a moment when a smuggler's son humbled an empire, reminding us that history often pivots on the audacity of the overlooked. Shifting from the annals of the past to the pulse of the present, the saga of Huang Chao's rebellion offers profound insights for personal growth. At its core, this historical fact underscores the power of challenging entrenched systems—whether imperial corruption or self-imposed limitations. By applying the outcomes of this event, individuals can harness the spirit of transformation to overhaul stagnant aspects of their lives, fostering resilience and proactive change. Here's how this ancient upheaval can motivate you today: - **Recognize and Confront Personal 'Corruptions'**: Just as Tang excesses fueled rebellion, identify toxic habits like procrastination or negative self-talk that erode your potential. Audit your daily routines to pinpoint drains on your energy, much like Huang spotted governmental weaknesses. - **Build Alliances for Strength**: Huang's army grew through recruitment; similarly, surround yourself with supportive networks. Seek mentors or accountability partners to amplify your efforts in pursuing goals, turning solo struggles into collective triumphs. - **Embrace Failure as Fuel**: Huang's exam flops propelled him forward—use setbacks, like job rejections or fitness plateaus, as catalysts. Reframe them as training for greater pursuits, building mental fortitude. - **Strategize Bold Moves**: The capture of Luoyang required calculated risks; map out ambitious steps in your career or health journeys, breaking them into sieges on smaller objectives for momentum. - **Sustain Momentum Amid Adversity**: Despite losses in the south, Huang pivoted north—cultivate adaptability by setting contingency plans, ensuring temporary defeats don't derail long-term visions. To integrate these lessons into a concrete plan, follow this step-by-step blueprint for personal rebellion against complacency: