Imagine a crisp December morning in 1282, the air biting like a wolf’s fang over the rolling hills of mid-Wales. Mist clings to the River Irfon like a shroud, and the wooden planks of Orewin Bridge creak under the weight of armored boots. A man in his fifties, clad in chainmail etched with the fierce red dragon of Gwynedd, urges his horse forward. His name is Llywelyn ap Gruffudd—Llywelyn the Last, Prince of Wales, the final flicker of a flame that had burned bright for centuries in the hearts of the Welsh people. He doesn’t know it yet, but today, December 11, will etch his name into the annals of defiance, not as a king crowned in glory, but as a leader felled by treachery, his head destined for a spike in London while his body vanishes into the anonymous earth of a forgotten abbey.

This isn’t just a tale of swords and sorcery from some dusty chronicle; it’s the raw, pulsating story of a man who dared to dream of a united Wales against the inexorable tide of English conquest. Llywelyn’s life was a whirlwind of alliances forged in blood, betrayals whispered in shadowed halls, and battles that echoed the thunder of ancient Celtic gods. His death at Orewin Bridge didn’t just end a dynasty—it slammed the door on Welsh independence for over two centuries, paving the way for Edward I’s iron-fisted annexation. Yet, in that very tragedy lies a vein of gold for us today: a lesson in resilient leadership, the power of cultural identity, and the audacity to stand firm when the world demands you kneel. We’ll journey deep into the mists of medieval Wales, unearthing the gritty details of Llywelyn’s world—the feuds, the feasts, the forgotten skirmishes—before turning that ancient fire into fuel for your own battles. Buckle up; this is history not as a lecture, but as a rally cry.

## The Forge of a Prince: Llywelyn’s Turbulent Birth into a Fractured Realm

To understand the man who would become the last native Prince of Wales, we must first step back to the rugged landscapes of 13th-century Gwynedd, a kingdom in northwest Wales where mountains like Eryri (Snowdonia) stood as natural fortresses against invaders. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd entered this world around 1223, though exact records are as elusive as a Welsh mist. He was the second son of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Iorwerth—better known as Gruffudd, the hot-headed eldest son of the legendary Llywelyn the Great (Llywelyn I). His mother, Senana ferch Caradog, hailed from the noble line of Anglesey lords, a lineage steeped in the salt spray of the Irish Sea and the fierce independence of the Isle of Môn.

Gwynedd in the 1220s was no idyllic bard’s ballad. It was a pressure cooker of dynastic intrigue, where succession wasn’t decided by gentle handovers but by the clash of steel and the whims of English kings. Llywelyn the Great had unified much of Wales through cunning diplomacy and brutal warfare, extracting homage from lesser princes and even forcing King John to recognize his overlordship in the 1210s. But his death in 1240 shattered that fragile mosaic. His legitimate son, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, seized the throne, imprisoning his half-brother Gruffudd (Llywelyn II’s father) in a tower at Dafydd’s court. Gruffudd, ever the rebel, was later handed over to England’s Henry III, who saw him as a useful pawn. In a bid for freedom in 1244, Gruffudd attempted a daring escape from the Tower of London, knotting bedsheets into a makeshift rope. The fabric snapped under his weight, and he plummeted to his death—a grim omen that would haunt his sons.

Young Llywelyn, barely out of boyhood, watched this chaos unfold from the fringes. By 1244, he held minor lands in the fertile Vale of Clwyd, a breadbasket region dotted with hill forts and druidic stone circles whispering of older magics. He joined a crusade to the Holy Land alongside Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother, perhaps to escape the family maelstrom or to burnish his credentials. But back home, tensions simmered. After Dafydd’s death in 1246—poisoned, some whispered, by English intrigue—his will carved up Gwynedd like a Christmas goose. The eastern lowlands (Perfeddwlad) went to Henry III, while the mountainous west (Gwynedd Uwch Conwy) was split between Llywelyn’s brothers: Owain Goch (the Red) and the younger Dafydd ap Gruffudd.

This Treaty of Woodstock in 1247 was a humiliating leash. Llywelyn, then in his early twenties, chafed under it. Owain and Dafydd’s rivalry exploded into open war by 1255, with Owain allying against his brother in a bid for dominance. Llywelyn, sidelined but seething, bided his time. Then came the Battle of Bryn Derwin in June 1255—a savage affair in the meadows near Cricieth Castle, where Llywelyn’s forces ambushed his brothers under a canopy of summer oaks. Owain was captured and imprisoned for years in the damp bowels of Cricieth, while Dafydd fled south, only to return as Llywelyn’s reluctant ally. At 32, Llywelyn stood alone as Prince of Gwynedd Uwch Conwy, his banner—a golden lion rampant on red—fluttering over Snowdonia’s peaks.

But power in medieval Wales was as slippery as river pebbles. Llywelyn’s early reign was marked by shrewd expansions. He crossed the River Conwy in November 1256, reclaiming Perfeddwlad from English sheriffs who had imposed crippling taxes and dismantled ancient Welsh laws like Cyfraith Hywel—the native legal code that emphasized compensation over capital punishment, a humane contrast to English brutality. By December, Dyserth Castle was the only English holdout, its walls echoing with the cries of Welsh rebels. Llywelyn’s army, a ragtag force of spearmen from the hills, archers from the woods, and bards chanting prophecies of victory, swelled with defectors.

The English response was thunderous. Henry III mobilized from Scotland to the Marches, but infighting among his barons—exacerbated by Simon de Montfort’s brewing rebellion—blunted their edge. In June 1257, at the Battle of Cadfan, Llywelyn’s forces routed an English column under Stephen Bauzan, sending Rhys Fychan, a Welsh turncoat lord, scurrying to his banner. Rhys’s submission was a coup; as overlord of Deheubarth in the south, he opened doors to Llywelyn’s ambitions. By Lent 1258, Llywelyn’s influence stretched to the Bristol Channel, liberating kinsmen in Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire. Feasts in his honor filled halls with mead and harp music, where poets like Llygad Gŵr lauded him as “the wall of the Welsh nation.”

Yet, truces were as fleeting as Welsh weather. The 1258 armistice crumbled when Marcher Lords—those semi-autonomous English barons on the Welsh border, like the Mortimers and de Clares—raided unchecked. Llywelyn struck back in 1260, expelling Roger Mortimer from Gwrtheyrnion, a forested lordship riddled with ancient trackways. Mortimer’s counterattack from Shrewsbury faltered amid baronial squabbles, leading to a two-year truce that Llywelyn used to consolidate. He imprisoned the treacherous Maredudd ap Owain in Cricieth until Christmas 1259, extracting a hostage son and fealty from Dinefwr Castle, a stronghold since the days of Hywel Dda.

It was in early 1258 that Llywelyn first styled himself “Prince of Wales” in charters, a bold claim echoing his grandfather’s dominion. The English court scoffed, but Scottish nobles, tied to the Comyn family, recognized it in alliances against Henry III. By 1263, even his brother Dafydd—ever the opportunist—bent the knee, though whispers of betrayal lingered like smoke from a dying fire.

## Alliances in the Storm: The Montfort Gambit and the Treaty of Montgomery

The 1260s thrust Llywelyn into the maelstrom of England’s Second Barons’ War, a civil strife that pitted Henry III’s absolutism against Simon de Montfort’s push for parliamentary reform. Llywelyn, ever the chessmaster, allied with the younger Montfort after the baron’s stunning victory at Lewes in 1264, where he captured Henry and the future Edward I. This was no mere opportunism; Montfort saw Llywelyn as a counterweight to the Marcher Lords gnawing at Wales’ edges.

In the Treaty of Pipton on June 22, 1265, Llywelyn pledged 25,000 marks—astronomical even by medieval standards—for peace, ceding castles like Dinefwr and Carreg Cennen but gaining breathing room. Pope Clement IV thundered excommunication threats from Avignon, branding Montfort a heretic, but Llywelyn pressed on. When Montfort fell at Evesham in August 1265—his body hacked to pieces by royalists—Llywelyn didn’t rush to aid. Instead, he campaigned ruthlessly: routing Hamo le Strange near Deganwy, torching English supply lines, and ambushing Roger Mortimer’s host at Montgomery, where Welsh longbows felled knights like autumn leaves.

The papal legate Ottobuono de Fieschi mediated, leading to the Treaty of Montgomery in September 1267—a pinnacle of Llywelyn’s power. Henry III, battered and broke, recognized him as Prince of Wales, granting overlordship of all Wales save the southern lordships. Llywelyn paid 24,000 marks in installments, confirmed by papal bull, and even purchased the homage of holdouts like Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg for another 5,000. Bards composed odes comparing him to Arthur, returned from Avalon to reclaim the isle.

But supremacy bred envy. Gilbert de Clare, the Red Earl of Gloucester, chafed at Llywelyn’s sway over Glamorgan, erecting the massive Caerphilly Castle—a moated behemoth that still defies time. After Henry’s death in 1272, the regency under Edward I (then on crusade) favored the Mortimers, who raided borderlands. Llywelyn’s annual payments lagged; homage at Chester in 1275 was refused amid slights—English sheriffs flogging Welsh envoys, seizing cattle under false pretenses.

In a romantic twist amid the geopolitics, Llywelyn wed Eleanor de Montfort in 1275. The daughter of Simon the Younger, born around 1258 on a ship fleeing Evesham, Eleanor was Henry III’s great-niece, making the union canonically fraught. Edward seized her at sea, imprisoning her at Windsor until Llywelyn groveled. They married properly at Worcester Cathedral on October 13, 1278, amid splendor: Scottish and English kings in attendance, Eleanor in silks embroidered with dragons. It was a love match, rare in royalty—no bastards shadowed their union, and Eleanor’s letters reveal a partnership of equals.

## The Cracks Widen: From Aberconwy to the Spark of Revolt

Peace under the 1267 treaty was a gilded cage. Edward I, crowned in 1272, returned from the Holy Land with a crusader’s zeal for order—and conquest. He flooded the Marches with sheriffs enforcing English common law, displacing Cyfraith Hywel’s restorative justice. Welsh tenants groaned under rents doubled overnight; bards decried the “Saxon yoke.” Llywelyn, now nearing 50, petitioned Archbishop John Peckham for mediation in 1280, but the prelate sided with Edward, calling Welsh customs “barbarous.”

Treacheries multiplied. Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn of Powys Wenwynwyn, a perennial turncoat, breached truces, his spies infiltrating Llywelyn’s councils. Yet Llywelyn reconciled with Dafydd, his ambitious brother, in secret plots to rally the uchelwyr—the Welsh nobility. By early 1282, discontent boiled over. On Palm Sunday, April 17, Dafydd struck first, storming Hawarden Castle under cover of night. The revolt ignited like dry tinder: Aberystwyth fell to flames, Carreg Cennen to siege, and whispers of unity spread from Anglesey to the Gower Peninsula.

Llywelyn, caught off-guard, disavowed initial plans in a letter to Peckham but threw his weight behind the uprising. “I did not begin this war,” he wrote, “but God knows I cannot end it without you.” English reprisals were swift: Edward’s host from Chester seized Anglesey, starving rebels of grain; Mortimer’s cavalry ravaged Builth. Welsh victories, like the ambush at Moel-y-don where a pontoon bridge of boats collapsed under English weight, were pyrrhic. Peckham’s peace overtures in summer 1282 demanded total surrender; Llywelyn refused, his response a clarion: “I will not yield my people, as did Kamber, son of Brutus, the ancient king of Britain.”

With Gwynedd under siege, Llywelyn rode south in autumn, a lone figure on a gaunt horse, rallying Mid Wales. His force—perhaps 500 spearmen and archers—hugged the high ground, evading English heavy cavalry in the boggy vales. On December 10, they camped near Builth Wells, a strategic ford where the Irfon met the Wye, its waters murmuring secrets of older battles.

## The Bloody Twilight: Chaos at Orewin Bridge

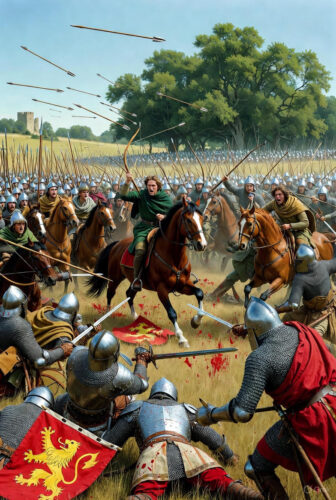

December 11 dawned gray and unforgiving. Llywelyn’s army controlled the hills flanking Orewin Bridge, a rickety span of oak over the swollen Irfon. Below, in the lowlands, English forces under Roger Mortimer, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, and Hugh le Strange mustered—knights in plate, longbows strung, banners snapping in the wind. Llywelyn’s plan was guerrilla: harry from above, deny the bridge, force a costly crossing. But fog and miscommunication sowed disaster.

As dawn broke, English scouts reported Welsh disarray. Mortimer’s cavalry—perhaps 800 lancers—thundered across the bridge in a desperate charge, hooves pounding like war drums. Llywelyn’s spearmen, caught reforming, panicked. The bridge held, but the Welsh line buckled; archers loosed volleys that felled horses but not the tide. Chaos erupted: men-at-arms hacked through the melee, Welsh fleeing into the woods, their cries swallowed by the river’s roar.

Llywelyn, separated from his main host, rode with a handful of retainers—18 by one account, including clerks and a priest—toward what he believed was a parley site. Accounts diverge here, as medieval chroniclers spun tales to suit patrons. The northern English version, penned decades later, paints him approaching Edmund Mortimer (Roger’s nephew) and le Strange post-battle, only to hear his army routed across the river. A lone English lancer, mistaking him for a foot soldier, struck him down with a lance through the heart. His men, scattered, couldn’t identify the body until days later.

A more vivid eastern monastic chronicle, laced with exiled Welsh whispers, adds treachery’s sting. Llywelyn, lured by false promises of homage from the Mortimers and Gwenwynwyn, ventured too far. As dusk fell, his rearguard clashed with Roger Despenser’s van; routed, they fled into Aberedw Wood, a tangled thicket of hazel and holly. Surrounded at twilight, Llywelyn dismounted, sword drawn, his dragon banner trampled in the mud. “A priest!” he gasped as a spear pierced his side, revealing his identity to his slayers. They hacked off his head, rifling his breeches for a “treasonous letter”—likely forged, listing phantom conspirators. His privy seal, Eleanor’s ring, and a scrap of vellum were seized.

Archbishop Peckham’s dispatches confirm the grim epilogue: on December 17, he relayed the “discovery” to Edward, enclosing the damning note. Llywelyn’s head, wreathed in ivy to mock the prophecy that a Welshman would wear a crown in London, was paraded through Anglesey to cow rebels. Borne to Rhuddlan, it thrilled Edward’s troops; then to the Tower of London, spiked over Newgate for 15 years, a grisly talisman until Henry IV buried it with honors in 1400.

His body? Smuggled to Cwmhir Abbey, a Cistercian outpost in Radnorshire’s wilds, for hasty interment. Peckham inquired on December 28 if it lay there before Epiphany, but fog of war obscured details. Chronicles speak of a “mangled trunk” in unconsecrated ground, or transfer to Llanrumney Hall. Poets like Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch wailed in elegy: “Cold my heart before you, / Under the feet of traitors…” The Brut y Tywysogion hints at betrayal in Bangor’s belfry—perhaps a metaphor for clerical complicity.

Casualties? English losses light; Welsh perhaps 2,000, though fog hides the butcher’s bill. Obscure facets linger: Orewin marked English archers’ debut integrated with cavalry, a tactic honed for future conquests. Llywelyn’s “conspirator list” may have been bait, planted by Gwenwynwyn’s spies. And that ivy crown? A cruel jab at Merlin’s prophecy, turning destiny’s promise into derision.

## Echoes of Defeat: The Conquest’s Iron Heel and Wales’ Long Shadow

Llywelyn’s fall was the domino that toppled Welsh autonomy. His brother Dafydd, proclaimed Prince in the chaos, held out six months—guerrilla raids from Snowdonia’s crags, alliances with Scots—but was betrayed in June 1283 at Bera Mountain. Captured with his wife and babes, he faced Shrewsbury’s Parliament: hanged, drawn, quartered, his head joining Llywelyn’s on London Bridge. Edward’s 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan carved Wales into shires, imposing English law, sheriffs, and castles—Beaumaris, Conwy, Harlech—like teeth in a trap.

Gwynedd’s treasures vanished: the coronation coronet to Westminster, the Cross of Neith paraded in 1285 pageants, seals melted for chalices at Vale Royal Abbey. Llywelyn’s daughter Gwenllian, a toddler, was spirited to Sempringham Priory, dying a nun in 1337. His brothers faded: Owain Goch vanished, Rhodri exiled to English manors. Distant kin like Owain Lawgoch plotted comebacks, but Edward’s grip held until Owain Glyndŵr’s 1400 blaze.

The significance? Llywelyn embodied Wales’ zenith—a unifier who extracted homage from 10 principalities, blending Celtic lore with feudal realpolitik. His wars accelerated Edward’s “first English empire,” but seeded resistance: bards preserved his myth, fueling Tudor nostalgia and modern nationalism. Sites like Cilmeri’s 1902 monument draw pilgrims, where wreaths mark the “last leader.” In a fun twist, legends claim his ghost haunts Builth’s woods, dragon-cloaked, whispering to lost hikers.

## Igniting Your Inner Dragon: Llywelyn’s Legacy as a Blueprint for Bold Living

Now, pivot from the blood-soaked fields of 1282 to your own arena—be it a cluttered desk, a stalled career, or a dream deferred. Llywelyn’s saga isn’t mere antiquity; it’s dynamite for the soul. He faced an empire’s shadow yet rallied a nation through vision, adaptability, and raw grit. His fall? Not defeat, but a testament to fighting for what endures: identity, community, purpose. In our fragmenting world of algorithms and isolation, Llywelyn teaches that true power blooms in defiance of the odds. Here’s how to channel that dragon fire into your life—specific, actionable sparks drawn from his unyielding arc.

– **Forge Unbreakable Alliances Like Llywelyn’s Montfort Pact**: In 1265, Llywelyn didn’t conquer alone; he bound rebels with shared stakes, turning foes into kin. Apply this by auditing your circle weekly: list three “Marcher Lords” draining your energy (toxic colleagues, fair-weather friends), then nurture two “Dafydd allies” with targeted outreach—a coffee invite to brainstorm goals, or a shared playlist of motivational tracks. Over a month, track how these bonds amplify your projects, mirroring how Llywelyn’s pacts swelled his host from hundreds to thousands.

– **Master the High Ground of Strategic Patience, as in the 1257 Cadfan Triumph**: Llywelyn lured English knights into boggy ambushes, turning terrain to tactic. In your battles—say, negotiating a raise—claim metaphorical heights: prepare dossiers on your wins (like Llywelyn’s charters), time strikes for weak moments (boss’s post-vacation haze), and retreat gracefully to regroup. Bullet this into daily ritual: mornings, map one “Irfon crossing”—a small win via preparation—building resilience so when big storms hit, you’re the archer, not the charger.

– **Wield Cultural Identity as a Shield, Echoing Cyfraith Hywel’s Endurance**: Llywelyn clung to Welsh laws amid English edicts, preserving a people’s soul. Revive your roots: dedicate Sundays to “Gwynedd rituals”—cook a family recipe while journaling heritage stories, or learn a skill from your lineage (guitar if Irish, coding if immigrant grit). This anchors you against modern “annexations” like social media burnout; measure benefit in quarterly mood logs, watching self-doubt shrink as pride swells.

– **Embrace Love as Battle Fuel, Per the Worcester Wedding Vow**: Llywelyn’s union with Eleanor wasn’t politics alone—it was partnership igniting his final push. Infuse yours: if single, craft a “Montfort manifesto”—three non-negotiables (kindness, adventure, depth) for dates; if coupled, revive with weekly “treaty nights” (no screens, deep talks). Track intimacy spikes via shared journals, transforming relational ruts into the emotional war chest Llywelyn drew from in 1282.

– **Turn Betrayal into Bardic Fuel, as Gruffudd’s Elegy Did**: Stabbed by kin like Gwenwynwyn, Llywelyn’s memory lived through poetry. When trust shatters—fired by a mentor, ghosted by a pal—ritualize response: write an “ab yr Ynad Coch” vent-poem, then alchemize it into action (pivot career via online course). Monthly, review these “elegies” for patterns, converting pain to propulsion, ensuring no Orewin becomes your end.

## Your Orewin Bridge Battle Plan: A 90-Day Charge to Defiant Victory

Llywelyn didn’t plan his fall—he charged south to rally the dispossessed. You won’t either. This 90-day blueprint, rooted in his campaigns, turns history into habit. Divide into phases: Recon (Days 1-30), Rally (31-60), Roar (61-90). Commit like Llywelyn to the Conwy crossing—no half-measures.

**Phase 1: Recon—Map Your Marches (Days 1-30)**

– Day 1: Audit empire—journal threats (work overload, health slips) and treasures (skills, supporters) like Llywelyn’s 1256 land scan.

– Weekly: One “Bryn Derwin ambush”—tackle a sibling rivalry or procrastination beast with a 20-minute confrontation script.

– End-month: Treaty of Woodstock self-pact—swear off one drain (doom-scrolling), reward with a solo hike echoing Snowdonia’s solitude. Goal: Clarity, as Llywelyn gained post-1255.

**Phase 2: Rally—Build Your Host (Days 31-60)**

– Daily: “Montgomery homage”—seek one fealty (mentor coffee, LinkedIn connect), tracking in a “vassal ledger” app.

– Bi-weekly: Cadfan drill—practice adaptability (role-play negotiations, pivot a failed workout to yoga).

– End-month: Eleanor vow—deepen one bond with a shared quest (book club, trail run), journaling the “love match” lift in energy. Goal: Momentum, swelling your forces like Llywelyn’s 1260s surge.

**Phase 3: Roar—Cross the Bridge (Days 61-90)**

– Daily: Irfon arrow—launch one bold strike (pitch idea, confess dream), debriefing failures as “ivy crowns” (humorous spins).

– Weekly: Peckham refusal—practice “no” to empire demands (overtime, people-pleasing), affirming in mirror: “I will not yield my people.”

– End-month: Cwmhir burial ritual—celebrate scars (tattoo? Poem?) and plot next revolt. Measure via pre/post surveys: resilience score up 30%. Goal: Legacy, ensuring your “head” inspires, not spikes.

Llywelyn’s roar faded into Welsh lore, but yours? It echoes eternally. On this December 11, 742 years later, stand at your Orewin. The river rushes; the bridge beckons. Charge not to fall, but to fly. The dragon awaits.