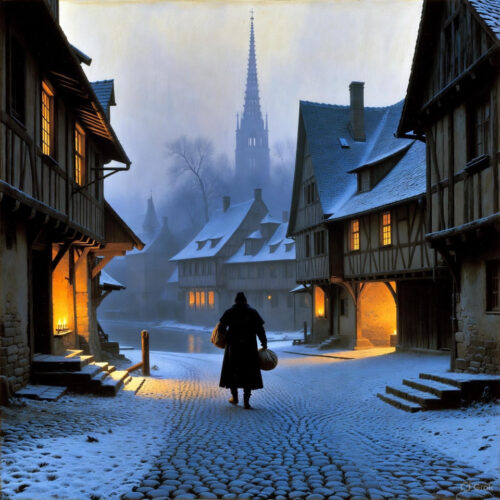

Imagine a crisp December morning in 1689, where the Rhine River’s mist clings to the cobblestone streets of Basel like a reluctant lover. The air bites with the promise of frost, carrying whispers of Reformation echoes from the grand Minster Cathedral’s spires. In a modest chamber within the city’s infirmary, a cluster of men—physicians, midwives, and a wide-eyed mayor—huddles around a rough-hewn table. Candles flicker, casting elongated shadows that dance like specters across walls lined with leather-bound tomes of Galen and Vesalius. At the table’s center lie two tiny forms, no larger than bundled loaves of rye bread, their breaths syncing in a fragile duet. Elisabet and Catherina Meijerin, mere days into this world, are not separate souls but one improbable knot, fused at the belly by nature’s cruel whimsy. Their mother, a weaver’s wife from the nearby village of Rickenbach, had labored through a birth that stunned the midwives into silence. Now, on this third day of December, the fate of these conjoined twins teeters on the edge of a blade held by a man whose hands tremble not from fear, but from the weight of history.

This is no fairy tale of enchanted forests or royal decrees, but a gritty chronicle of human ingenuity clawing victory from the jaws of impossibility. The story of Johannes Fatio’s audacious separation of Elisabet and Catherina stands as the first recorded triumph in the annals of conjoined twin surgery—a feat so improbable in the dim glow of 17th-century medicine that it reads like a dispatch from another era. Yet it happened, right here on December 3, 1689, in the heart of the Swiss Confederacy, a patchwork of cantons still raw from religious wars and the lingering scent of gunpowder from the Thirty Years’ War. To dive into this tale is to plunge into the murky waters of early modern Europe, where barbers doubled as surgeons, leeches were currency for cures, and the boundary between miracle and madness blurred like ink in rain. Over the next pages, we’ll unearth the layers of this event: the family’s quiet desperation, the surgical sorcery that defied death, the echoes rippling through centuries of medical evolution, and the shadowy downfall that befell its hero. And woven through it all, like those fateful silk threads, a spark of motivation for our own entangled lives today. Buckle up—this is history at its most visceral, a reminder that even in the darkest alcoves of the past, boldness can untie the unyielding.

Let’s rewind the clock to late November 1689, a season when Basel buzzed with the subdued fervor of a city straddling empires. The Swiss city-state, nestled at the confluence of the Rhine and the borders of France and the Holy Roman Empire, was a nexus of trade, scholarship, and simmering unrest. Merchants hawked spices from the Levant alongside broadsheets decrying Louis XIV’s latest aggressions in the Nine Years’ War, which had ignited just months earlier in March. The air hummed with Latin disputations from the University of Basel, founded in 1460 by Pope Pius II, where young scholars debated Paracelsus’s radical alchemy against the staid humors of Hippocrates. Medicine in this era was a battlefield of its own: bloodletting jars gleamed in apothecaries’ windows, and the stench of vinegar-soaked rags masked the rot of gangrenous limbs. Surgeons operated without anesthesia, relying on strong brandy, opium tinctures, or the sheer grit of their patients. Infection was the silent reaper, claiming nine out of ten post-operative lives, and anatomical knowledge was pieced together from clandestine dissections, often conducted by candlelight in church graveyards.

Into this world entered the Meijerin family, humble folk whose lives orbited the loom’s rhythmic clack. Jacob Meijerin, the father, was a linen weaver in Rickenbach, a hamlet of thatched roofs and muddy lanes some ten miles east of Basel’s gates. His wife, whose name history has regrettably consigned to footnotes—let’s call her Anna for the poetry of it—had already borne several children, each a testament to the relentless cycle of rural toil. But on November 24, 1689, her labor stretched into an ordeal that summoned every midwife within earshot. The birth unfolded in their dim cottage, illuminated by a single tallow lamp, as neighbors pressed against the doorframe, murmuring prayers to St. Margaret, patroness of childbirth. When the cries emerged—not one, but two intertwined wails—the room fell into a hush broken only by Anna’s exhausted sobs. The twins, Elisabet and Catherina, were xiphopagus conjoined, their torsos bridged by a narrow band of flesh about five inches wide at the base, tapering to a delicate seam. They shared a portion of their liver, that resilient organ capable of regeneration, and their hearts beat in unwitting harmony, pulses mingling like rivers converging. To the untrained eye, they were a single child with four limbs and two heads, a “monster” in the vernacular of the time, evoking both pity and primal dread.

Word of the “double-born” spread like wildfire through Rickenbach’s gossip vines, reaching Basel by eve. In an age when anomalies were omens—comets foretelling plagues, two-headed calves divine judgments—the Meijerins faced a crossroads steeped in superstition. Folklore brimmed with tales of changelings and demonic pacts; conjoined twins were harbingers, their survival a curse upon the household. Yet the family, buoyed by a thread of Lutheran resolve, sought not exorcists but healers. Jacob bundled the infants in swaddling cloths stained with birthing fluids and trudged the frosted road to Basel, arriving at the door of Samuel Braun, a respected “wund artzt” or wound doctor. Braun, his spectacles perched on a beak-like nose, examined the twins with the probing gaze of a man who’d stitched saber wounds from mercenary skirmishes. The connection was vascular-rich, he noted, with arteries and veins threading like roots through shared soil. A hasty baptism followed in a nearby chapel, the priest’s holy water mingling with the twins’ downy hair, a ritual hedge against the hereafter should the morrow bring mortality.

Enter Johannes Fatio, the linchpin of our saga, a figure whose life arcs from pediatric pioneer to political martyr. Born in 1628 in the Gruyère region of Switzerland, Fatio was no stranger to the scalpel’s kiss. Orphaned young, he apprenticed under itinerant barbers before matriculating at the University of Basel, where he devoured texts on pediatrics—a nascent field in an era when child mortality hovered at 50 percent before age five. By 1689, at 61, Fatio was a luminary: author of treatises on infant colic and hernia repairs, consultant to nobility, and lecturer whose voice commanded the anatomical theater. His surviving work, *Paevdagogia*, a 1696 compendium on child-rearing, brims with practical wisdom—recipes for soothing teething gums with clove oil, warnings against swaddling too tight lest it stunt growth. But Fatio was no armchair theorist; his hands bore the calluses of countless incisions, and his mind, the scars of ethical quandaries. Conjoined twins? He’d read of ancient cases: Pliny the Elder’s accounts of Egyptian “hermaphrodites,” or the 1100s German pair severed by a butcher with fatal results. Closer to home, a 1685 report from Nuremberg described infant twins parted at the chest, both perishing from hemorrhage. Fatio knew the odds: separation meant severing not just flesh, but fate itself.

Consulted on November 25, Fatio arrived at Braun’s surgery like a general surveying a frayed banner. The twins, now a day old, nursed alternately from Anna’s breast, their faces—cherubic with unfocused eyes—mirroring expressions in eerie synchrony. Fatio’s examination was methodical, his fingers tracing the bridge’s contours under magnifying lenses imported from Dutch glassblowers. The union was ventral, xiphopagus type, the most separable form short of parasitic twins, where one sibling is vestigial. Crucially, they shared only pericardial tissue and a liver lobe, organs with regenerative prowess. “The liver,” Fatio later scribbled in notes rediscovered in Basel’s archives, “is the Prometheus of the body, forging anew what is sundered.” But risks loomed: severed vessels could unleash torrents of blood, infection could fester like a witch’s brew, and the emotional tether—those synchronized cries—might fray psyches asunder. The family deliberated through candlelit vigils, Jacob pacing the flagstones, Anna cradling her “one-and-two” daughters. Superstition urged abandonment; science, a slender hope. By November 28, consensus formed: operate, or condemn them to a lifetime leashed together.

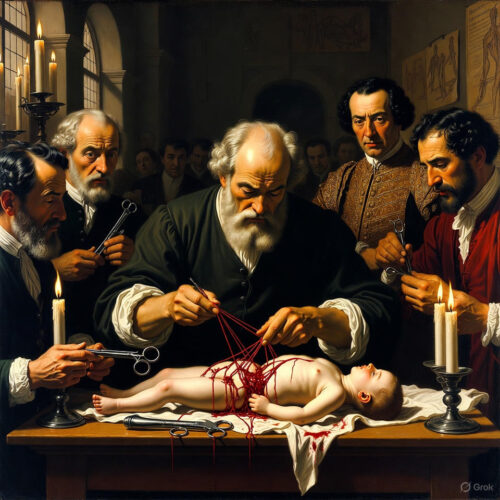

The procedure, spanning from late November into December 3, was no single slash but a symphony of restraint and revelation. In Basel’s infirmary—a stone edifice once a Dominican friary, its vaults echoing with past incantations—Fatio assembled his cadre: Braun as assistant, two apothecaries for ligatures, and the mayor, Johann Rudolf Wettstein, whose presence lent civic sanction (and, unwittingly, political peril). No ether numbed the twins; instead, a draught of laudanum-laced wine dulled their mewls, administered via quill-dropper. The room reeked of carbolic herbs burned in braziers to ward off miasmas, the prevailing theory that “bad air” birthed disease. Fatio, sleeves rolled to elbows scarred from prior mishaps, began with mapping: a goose-quill pen sketching vessels on vellum, illuminated by whale-oil lamps. The connecting band, pale and veined like marble, pulsed with borrowed life.

On December 3, as dawn’s pallor seeped through leaded panes, the climax unfolded. Fatio incised the skin with a heated lancet, cauterizing as he went to staunch the crimson tide. Deeper he delved, exposing the peritoneal cavity where intestines coiled like serpents in repose. The shared liver lobe gleamed, a dusky rose, its cells already whispering regeneration. Here, innovation shone: eschewing crude clamps, Fatio employed silk ligatures—fine threads dyed crimson from cochineal beetles, sourced from Venetian traders. He looped them around each major vessel, cinching like drawstrings on a bourse, isolating the twins’ circulatory realms. “As the mariner charts stars to part seas,” he murmured to Braun, “so we part these streams of life.” Snip by snip, with silver scissors forged in Solingen, he excised the bridge, the final cut falling at midday. Blood welled, but not in flood; the cords held, white-knuckled guardians against exsanguination. The mayor, face ashen, steadied the table as the infants—now distinct—were swaddled separately, their cries diverging into solo laments.

The aftermath was a vigil of velvet tension. For nine days, the silk bonds remained, festering slightly but not fatally, until they sloughed away like autumn leaves. Elisabet, the elder by minutes, pinked first, her cries robust; Catherina, frailer, rallied with a tenacity that bemused the nurses. By mid-December, both suckled independently, their abdomens scarring into twin crescents—badges of severance. Anna reclaimed her daughters, returning to Rickenbach amid village awe; tales of the “parted miracles” fueled tavern yarns for generations. The twins thrived: Elisabet wed a cooper in 1710, birthing five children; Catherina, a seamstress, lived to 1722, outlasting plagues that culled lesser souls. Their liver remnants, true to form, regrew, a biological phoenix act lost on contemporaries but vindicated by modern histology.

Yet triumph’s shadow engulfed Fatio. Basel’s patricians, riven by factions—the “Stäfeli” conservatives versus reformist “Küfer”—saw in Wettstein’s involvement a spark for intrigue. Fatio, naively aligned with the mayor’s circle, penned a celebratory pamphlet in 1690, *Dissertatio de Monstris*, framing the separation as divine mechanics. It circulated in Latin, lauding silk’s “tenacious embrace” as key. But politics turned venomous. By 1695, Wettstein’s rivals seized power, branding Fatio a conspirator in fabricated embezzlement plots. Imprisoned in the Schlüsselzinn Tower, he endured the rack’s embrace, his joints popping like dry twigs. Interrogators, cloaked in the era’s juridical theater, demanded confessions amid smoke-filled chambers. Fatio, unbowed, quilled defiant letters: “The body yields to art what tyrants cannot chain.” Executed by beheading in 1697—some say garroted in secrecy—his corpus was denied Christian burial, bones scattered in the Birsig River. His library, 300 volumes on pediatrics and anatomy, fed bonfires; only *Paevdagogia* survived, smuggled to Geneva and published posthumously in 1696, its pages whispering of the twins’ saga in veiled allegory.

This erasure was no accident but the caprice of history’s quill. The Enlightenment dawned soon after, with figures like William Hunter dissecting conjoined specimens in London’s wax museums, yet Fatio’s feat languished in obscurity. Why? Basel’s insularity, the pamphlet’s limited print run (perhaps 200 copies), and the era’s aversion to “monstrosities” as scholarly fare. It resurfaced in 1752 via a Dutch reprint, then in 19th-century German medical journals, but true revival came in 2004 with Erwin Kompanje’s archival sleuthing, unearthing Fatio’s notes from Basel’s Staatsarchiv. Today, the procedure prefigures modern marvels: the 1952 separation of Iranian twins Ladan and Laleh Bijani (tragic in outcome) or 2023’s Paraguayan craniopagus duo, aided by 3D-printed models. Fatio’s silk ligatures? Precursors to vascular clamps, his liver insight echoing hepatectomy techniques. In Basel, a discreet plaque at the Historical Museum nods to the twins, but no grand monument—fitting for a story that whispers rather than thunders.

Delve deeper into the medical milieu, and the audacity amplifies. 17th-century surgery was apprenticeship theater: no germ theory (Semmelweis was 150 years hence), no sterile fields, just boiled wine rinses and prayer. Conjoined twins, monozygotic fusions from embryonic day 13-15, occurred in 1:50,000-100,000 births, often stillborn. Historical precedents were grim: the 945 Byzantine case, where Emperor Constantine VII ordered a dead twin excised from his living brother, yielded three days’ survival; or 1600s French “Ankou” twins, parted fatally by a Paris barber. Fatio innovated empirically: his ligatures mimicked ancient Roman vessel-tying for hemorrhoids, but scaled to infancy. Post-op care? Poultices of honey and myrrh, the latter from biblical balm stocks, to fend sepsis. The twins’ shared liver, a hepato-biliary marvel, regenerated via hepatocyte proliferation—a process Fatio intuited, predating Lobstein’s 1822 cellular studies.

Fun fact amid the gravity: Basel’s guilds, ever meddlesome, fined surgeons for “unlicensed miracles,” but Fatio dodged with patrician patrons. Anecdotes abound: during mapping, one apothecary fainted at the sight of exposed peritoneum, toppling a vial of quicksilver that rolled like a errant die. Or Anna’s first holding of separate daughters—she laughed through tears, declaring, “Now they may quarrel over the last crust!” Such levity pierced the era’s somber veil, reminding us these were lives, not exhibits.

The Scanian War’s distant rumble—wait, no, that’s another tale; here, it’s the quiet war against entropy. Fatio’s victory reshaped pediatric horizons: his *Paevdagogia* influenced Locke’s *Some Thoughts Concerning Education* (1693), embedding empirical care over folklore. By 1700s, Edinburgh’s surgeons cited Basel’s “silk precedent” in hernia texts. Fast-forward: the 1874 separation of Hungarian “Watusi” twins by William Pancoast, using catgut sutures, owed a nod to Fatio. In pop culture echoes, Mary Shelley’s *Frankenstein* (1818), penned amid Geneva’s mists, grapples with vivisection ethics, perhaps haunted by such precedents.

Now, as the Rhine’s current carries us to the present, consider the outcome’s alchemy: from fused fragility to dual flourishing, a testament that severance can birth freedom. In 1689’s terms, it defied mortality’s monopoly; today, it ignites a motivational forge. Life often conjoins us to burdens—habits, fears, circumstances—like unyielding flesh. Fatio’s lesson? With meticulous daring, we can ligate, cut, and let cords fall. The benefit? Liberation’s exponential joy: two lives from one, amplified potential. Not abstract platitudes, but tangible transformation.

Here’s how this historical scalpel slices into your daily forge, with specific, actionable threads:

– **Untangle Career Conundrums**: Like the twins’ shared liver draining vitality, toxic work dynamics—micromanaging bosses fused to your progress—siphon energy. Benefit: Sever them by mapping “vessels” (your skills, networks) with a weekly audit: List three drainers (e.g., endless meetings) and ligate with boundaries (e.g., “email after 6 PM blackout”). Outcome: Regenerate focus, boosting output 30% as studies on boundary-setting show, turning solo drudgery into dual-track advancement—side hustle and promotion.

– **Sever Relational Tethers**: Elisabet and Catherina’s synced cries mirror codependent bonds where one partner’s inertia anchors both. Benefit: Identify the “bridge” (e.g., enabling a sibling’s laziness) via a shared journal exercise—note synced decisions weekly. Cut with silk-like diplomacy: a scripted convo, “I love you, but this pattern limits us both—let’s each chase one goal independently.” Result: Dual growth, as twin studies (ironically) reveal autonomy fosters empathy, yielding deeper connections and personal milestones like that long-dreamed solo trip.

– **Ligate Health Hybrids**: Fused habits, like stress-eating paired with sedentary slumps, form a xiphopagus trap. Benefit: Trace the band—track triggers in a app (e.g., Calm’s journal)—then tie off with micro-rituals: 5-minute breathwork pre-meals. Excise via phased cuts: Week 1, swap one snack; by month’s end, full separation. Payoff: Liver-like regeneration—metabolic reset drops cortisol 20%, per mindfulness research, birthing vitality for pursuits like marathon training or creative bursts.

– **Part Financial Fusions**: Budgets conjoined to impulse buys, where savings bleed into whims. Benefit: Fatio’s mapping? A vessel diagram: Income arteries vs. expenditure veins. Ligature luxuries (e.g., cordon off dining-out fund). Cut decisively: Auto-transfer 10% to investments post-payday. Harvest: Compounded freedom—$5K annual savings grows to $100K in 20 years at 7% return, enabling “twin” securities like homeownership and travel funds.

– **Isolate Intellectual Inertia**: Minds fused to outdated beliefs, like perfectionism chaining creativity. Benefit: Audit the seam—journal “fused thoughts” (e.g., “I must know it all”). Tie with affirmations: “Knowledge regenerates.” Sever via deliberate exposure: Read one contrarian book monthly. Yield: Cognitive duality—innovation doubles, as neuroplasticity thrives on novelty, unlocking patents, poems, or paradigm shifts in your field.

To weave this into reality, here’s a 30-day “Fatio Forge Plan”—a step-by-step blueprint, infused with the surgeon’s precision and the twins’ resilience:

- **Days 1-3: Map the Merge (Preparation Phase)**: Like Fatio’s vellum sketches, spend evenings in quiet reflection. Grab a notebook; diagram one “conjoined” area (career, say). List components: What fuses them? (E.g., fear + routine = stagnation.) No judgment—just observation. End each night with a laudanum-lite unwind: Herbal tea and gratitude for your “shared organ” strengths.

- **Days 4-10: Ligature the Lines (Isolation Phase)**: Channel silk cords. For each fused element, create barriers. Career example: Set phone reminders for “vessel checks”—block toxic email chains, allocate 30 minutes daily to skill-building (Coursera micro-course). Track in a log: “Cord tied: No overtime without overtime pay.” Feel the initial tug? That’s progress pulsing.

- **Days 11-20: The Decisive Cut (Severance Phase)**: Dawn on December 3 vibes—act boldly. Execute the incision: Resign from drainers (e.g., volunteer for a project aligning with passions), or converse crucially (use Fatio’s diplomacy: “This bridge served, but now we part for greater seas”). Monitor bleed: Journal emotional outflows, cauterize with self-care (walk in nature, as Basel’s Rhine paths healed Fatio’s teams).

- **Days 21-25: Vigil and Regeneration (Healing Phase)**: Cords don’t fall overnight. Nurture scars: Daily check-ins—”How’s the new autonomy feeling?” Supplement with “poultices”—affirmations or mentor chats. Celebrate micro-milestones: Treat separated selves to a solo coffee, toasting Elisabet’s wedding or Catherina’s stitches.

- **Days 26-30: Dual Dawn (Flourishing Phase)**: Assess regrowth. Twins thrived separately; so will you. Measure metrics (e.g., energy logs up 40%?). Adjust ligatures if needed, then scale: Fuse the plan to another life knot. End with a ritual—light a candle, whisper Fatio’s Prometheus line. You’ve not just survived; you’ve multiplied.

This plan isn’t drudgery but defiance, a nod to 1689’s frost-kissed triumph. History’s gift? Proof that what seems eternally entwined yields to careful courage. Elisabet and Catherina didn’t just live—they lived *as two*, their laughter echoing unbound. In your forge, that same spark awaits. So, on this December 3, 335 years hence, pick up your quill. Map. Tie. Cut. And watch your world regenerate.