Imagine a tropical island paradise turned into a hellish plantation empire, where hundreds of thousands of enslaved people toiled under the whip, producing unimaginable wealth for distant overlords. Now picture those same oppressed souls rising up, not just to survive, but to shatter the chains of one of the world’s mightiest armies. On November 18, 1803, in the rugged hills near Cap-Français in what is now Haiti, a ragtag force of former slaves delivered a stunning blow to Napoleon’s dreams of colonial dominance. The Battle of Vertières wasn’t just a military clash—it was the thunderous climax of the Haitian Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in history that birthed a free nation. This isn’t a tale of distant dusty tomes; it’s a vibrant saga of human spirit, cunning strategy, and unbreakable resolve that echoes through time. Dive in with me as we explore the depths of this pivotal moment, packed with intrigue, heroism, and hard-won lessons. And stick around, because we’ll uncover how this 222-year-old victory can supercharge your life today, turning everyday challenges into triumphs.

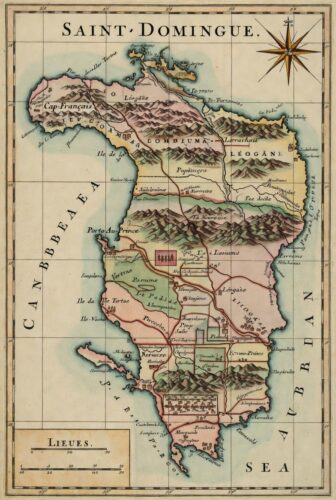

Let’s set the stage properly, because to grasp the magnitude of Vertières, we need to journey back to the roots of Saint-Domingue, the French colony that became Haiti. In the late 18th century, this western half of the island of Hispaniola was a jewel in France’s crown, often called the “Pearl of the Antilles.” Its economy was a machine of exploitation, churning out sugar, coffee, indigo, and cotton that fueled Europe’s sweet tooth and luxury markets. By 1789, Saint-Domingue produced about 60% of the world’s coffee and 40% of its sugar, making it more profitable than all of Britain’s Caribbean colonies combined. But this wealth rested on a foundation of horror: around 700,000 enslaved Africans, imported at a staggering rate to replace those who died from overwork, disease, and brutality. The average lifespan for a newly arrived slave on a plantation was just seven years. Planters enforced a regime of terror, with punishments like whipping, branding, and even burying people alive for minor infractions. The Code Noir, a 1685 French law meant to regulate slavery, was largely ignored, allowing owners unchecked power.

Society in Saint-Domingue was a powder keg of racial and class divisions. At the top were the grands blancs, the wealthy white plantation owners who lived like kings, hosting lavish balls and importing fine wines from Bordeaux. Below them were the petits blancs, poorer whites who worked as overseers or artisans, resenting their richer counterparts. Then came the gens de couleur libres, free people of color, often mixed-race descendants of white planters and enslaved women. Numbering about 28,000 by the revolution’s eve, many were educated, owned land, and even held slaves themselves, but they were denied full citizenship rights, like voting or holding high office. At the bottom were the enslaved, mostly African-born from regions like the Kingdom of Kongo, Dahomey, and Yorubaland. They brought with them rich cultural traditions, blending them into Vodou, a spiritual practice that mixed African religions with Catholicism. Vodou wasn’t just faith—it was resistance, providing secret gatherings where plots could be hatched under the guise of rituals.

The spark that ignited this tinderbox came from across the Atlantic: the French Revolution of 1789. News of the storming of the Bastille and the Declaration of the Rights of Man reached Saint-Domingue, stirring hopes among the oppressed. The declaration proclaimed “liberty, equality, fraternity,” but did it apply to colonies? Free people of color thought so, petitioning for equal rights. In October 1790, Vincent Ogé, a wealthy mulatto, led a brief revolt demanding citizenship, only to be captured and brutally executed on a breaking wheel. Whites, fearing loss of control, cracked down harder. Meanwhile, enslaved people whispered of freedom, inspired by figures like François Mackandal, a maroon leader executed in 1758 for poisoning planters. Maroons—escaped slaves living in mountain communities—raided plantations, keeping the spirit of rebellion alive.

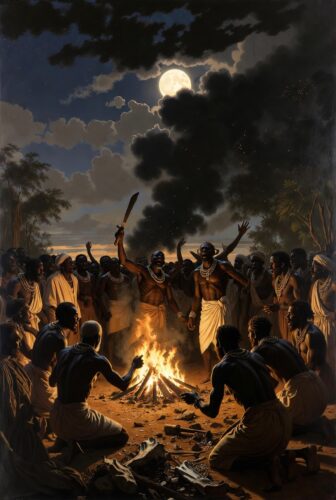

The revolution erupted on the night of August 21, 1791, in the northern plains. It began with a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman, where a high priest named Dutty Boukman and a priestess, Cécile Fatiman, rallied hundreds of slaves. Legend has it Boukman proclaimed, “God who created the sun which gives us light… orders us to revenge our wrongs.” That night, flames engulfed sugar cane fields as rebels slaughtered overseers and burned mansions. Within weeks, 100,000 slaves had joined, destroying over 1,000 plantations and killing 4,000 whites. The revolt spread south, where leaders like Romaine-la-Prophétesse, a self-proclaimed prophet, seized towns like Léogâne. Whites fled to Le Cap (now Cap-Haïtien), the colony’s bustling capital with its theaters and markets, now a refuge under siege.

France’s response was chaotic. The National Assembly granted citizenship to free people of color in April 1792, but it was too late to quell the uprising. Commissioners Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel arrived with troops, but facing invasion threats from Britain and Spain—who saw opportunity in the turmoil—they took a bold step. On August 29, 1793, Sonthonax abolished slavery in the north to win black loyalty, extending it colony-wide by October. This was ratified by France in February 1794, making Saint-Domingue the first place to end slavery en masse.

Enter Toussaint Louverture, the revolution’s towering figure. Born enslaved around 1743, he was freed in his 30s and became a coachman. Self-educated, fluent in French, and a skilled horseman, Toussaint joined the rebels in 1791, initially allying with Spanish forces from neighboring Santo Domingo. But when France abolished slavery, he switched sides in May 1794, declaring, “I am Toussaint Louverture; my name is perhaps known to you. I have undertaken to avenge your wrongs.” Under his command, black forces repelled Spanish invaders and turned on the British, who had seized ports like Jérémie and Port-au-Prince in 1793. The British “great push” of 1794-1796 faltered against guerrilla tactics and yellow fever, a mosquito-borne plague that decimated European troops unused to the tropics. By 1798, the British withdrew after losing 25,000 men, mostly to disease.

Toussaint consolidated power, defeating mulatto rival André Rigaud in the 1799 War of Knives (or War of the South), a brutal civil conflict that saw massacres on both sides. With U.S. naval help—President John Adams saw Toussaint as a trade partner—he captured Jacmel. By 1801, Toussaint controlled the entire island, invading Spanish Santo Domingo to free slaves there. He promulgated a constitution making him governor-for-life, abolishing slavery forever but enforcing strict labor on plantations to revive the economy. Toussaint’s rule was authoritarian yet progressive: he promoted education, rebuilt infrastructure, and invited white émigrés back under protection.

But Napoleon Bonaparte, who seized power in France in 1799, had other plans. Viewing colonies as vital to his empire, he secretly plotted to restore slavery. In 1802, he dispatched his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc, with 20,000 elite troops—the largest expeditionary force ever sent by France—to reconquer Saint-Domingue. Leclerc arrived in February, promising to uphold emancipation but with orders to deport black leaders. Fierce resistance ensued. At the Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres on February 23, Toussaint’s forces repelled General Donatien de Rochambeau. The siege of Crête-à-Pierrot in March saw Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint’s fierce lieutenant, hold a fort against 12,000 French, inflicting heavy casualties before a daring nighttime escape.

Yellow fever struck the French like a divine curse. By June, 10,000 soldiers were dead, including Leclerc himself in November. Toussaint, lured into negotiations, was arrested on June 7, 1802, and shipped to France, where he died in the cold Fort de Joux on April 7, 1803. His parting words: “In overthrowing me, you have cut down only the trunk of the tree of black liberty in Saint-Domingue; it will spring back from the roots, for they are numerous and deep.”

With Toussaint gone, resistance fragmented but reignited when Napoleon’s intent to restore slavery became clear. Leclerc’s successor, Rochambeau, unleashed atrocities: drowning blacks in bays, using attack dogs imported from Cuba, and gassing prisoners with sulfur dioxide. This backfired, uniting former rivals. Dessalines, a former slave known for his ruthlessness, emerged as leader. Born around 1758 in Guinea, he had scars from whippings and a burning hatred for the French. Henri Christophe, another ex-slave and skilled organizer, and Alexandre Pétion, a mulatto artillery expert, joined him. Polish legions sent by Napoleon—5,000 strong—defected en masse after witnessing French cruelties, many staying in Haiti as citizens.

By October 1803, the rebels controlled most of the island. British warships, at war with France again, blockaded ports, starving French garrisons. Rochambeau hunkered down in Cap-Français with 5,000 men, reduced to 2,000 fit for duty by disease. Dessalines besieged the city, capturing surrounding forts. The stage was set for Vertières, a hilly outpost south of Cap-Français, named after its vertical terrain. Here, on the site of an old plantation where Toussaint once worked, the final drama unfolded.

November 18, 1803, dawned tense. Dessalines commanded 27,000 rebels, a mix of battle-hardened veterans and fresh recruits, armed with captured muskets, machetes, and makeshift pikes. They lacked uniforms but wore determination like armor. Rochambeau’s forces, entrenched in Fort Bréda and the Vertières ramparts, had superior artillery but were demoralized, hungry, and fever-racked. The battle began at dawn when a low-ranking rebel, Clervaux, fired the first shot as French trumpets blared.

François Capois, a charismatic officer nicknamed “Capois-la-Mort” (Capois the Deathless), led the charge. Mounted on a great Turkoman horse, he galloped his demi-brigade toward the French lines. Cannon fire tore through the ranks, but the rebels pressed on, singing revolutionary songs to drown out the fear. They navigated a ravine under withering grapeshot, bodies piling up as survivors climbed over the fallen, shouting “Forward!” Capois’s horse was shot out from under him; he staggered, drew his saber, and charged on foot, bellowing encouragement.

From the ramparts, Rochambeau watched in awe. As Capois advanced unscathed through a hail of bullets—his hat and epaulettes shot away but himself untouched—the French drums beat a cease-fire. A staff officer rode out, saluting Capois: “The Captain-General salutes such bravery!” The moment passed, and fighting resumed. Dessalines committed reserves under young General Gabart and Jean-Philippe Daut. A French counterattack faltered against the rebels’ ferocity. Then, a sudden tropical storm erupted—thunder, lightning, pouring rain—turning the field to mud and masking Dessalines’s maneuvers.

By afternoon, the French were broken. Casualties mounted: 1,200 rebels dead or wounded, matching French losses, but the attackers’ numbers overwhelmed. Rochambeau retreated to Cap-Français under the storm’s cover, admitting defeat. The next day, he sued for peace, agreeing to evacuate within ten days. On November 30, the last French ships sailed away, carrying 8,000 survivors to captivity in Britain. Left-behind wounded French were promised safety but many were drowned by vengeful rebels.

Vertières sealed Haiti’s fate. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines proclaimed independence in Gonaïves, renaming the nation “Haiti” after the indigenous Taíno word for “mountainous land.” The new flag was made by ripping the white from the French tricolor, symbolizing the expulsion of whites. But victory came at a cost: over 200,000 Haitians dead from war and disease, the economy in ruins, plantations abandoned. Dessalines ordered a massacre of remaining whites in 1804, killing 3,000-5,000, sparing only Poles, Germans, and a few others who aided the cause.

Haiti’s independence terrified slaveholding nations. The U.S. refused recognition until 1862, fearing inspiration for its own slaves. France demanded reparations: in 1825, King Charles X extorted 150 million francs (later reduced to 90 million) for diplomatic recognition, a debt Haiti paid until 1947, crippling its development. Yet, Haiti became a beacon: it aided Simón Bolívar’s Latin American revolutions, providing arms and men in exchange for abolishing slavery.

The revolution’s legacy is profound. It proved enslaved people could overthrow empires, influencing abolitionist movements worldwide. Vodou, once demonized, emerged as Haiti’s national religion. Leaders like Toussaint and Dessalines became icons—flawed heroes who blended vision with violence. Toussaint’s strategic genius, blending diplomacy and warfare, turned a slave revolt into a national army. Dessalines’s unyielding fury ensured no turning back. Vertières wasn’t just a battle; it was humanity’s stand against oppression, showing that unity and courage can topple giants.

Now, fast-forward to today. The echoes of Vertières aren’t confined to history books—they’re tools for your personal arsenal. In a world of modern “empires” like corporate grind, toxic relationships, or self-doubt, the Haitian rebels’ triumph offers a roadmap to liberation. Here’s how you can channel that revolutionary spirit into your life, turning historical grit into daily wins.

– **Embrace Radical Self-Emancipation**: Just as the slaves rejected their chains, identify what’s enslaving you—maybe a dead-end job or negative habits. Start by auditing your day: track time spent on draining activities versus fulfilling ones. Commit to one “abolition” act weekly, like quitting social media scrolling after 8 PM to reclaim mental freedom.

– **Build Alliances Like Toussaint**: Toussaint forged unlikely partnerships, from mulattos to defecting Poles. In your life, seek mentors or accountability buddies. Join a mastermind group or online community focused on your goals, such as a fitness app forum if you’re battling health issues. Share vulnerabilities to build trust, turning solo struggles into collective power.

– **Face Fears with Capois’s Bravery**: When bullets flew and his horse fell, Capois charged forward. Apply this to public speaking anxiety: practice in low-stakes settings, like recording yourself daily, then escalate to Toastmasters meetings. Reward each step with something fun, like a favorite treat, to make courage addictive.

– **Use Guerrilla Tactics Against Overwhelm**: Rebels won with hit-and-run strategies, not head-on clashes. Break big goals into micro-attacks: if debt is your “Napoleon,” automate $50 monthly payments while negotiating lower rates. Track progress in a journal to see how small wins compound into victory.

– **Weather Storms Like the Battle’s Downpour**: The rain masked retreat and advance—use life’s setbacks as cover for regrouping. After a job loss, take a “storm day” for self-care, then pivot: update your LinkedIn, network via three coffee chats weekly, and upskill with free online courses.

– **Declare Your Independence Daily**: Dessalines proclaimed freedom boldly. Write a personal manifesto outlining your values and non-negotiables, like “I prioritize health over hustle.” Read it aloud each morning to reinforce autonomy.

To make this actionable, here’s a 30-day Vertières-Inspired Freedom Plan:

- **Days 1-7: Reconnaissance Phase** – Map your “colony”: list five areas where you feel trapped (e.g., finances, relationships). Research one historical rebel tactic daily, like Toussaint’s diplomacy, and brainstorm modern applications.

- **Days 8-14: Mobilization Week** – Rally resources: assemble a “rebel army” of three supportive people. Set one small goal per area, such as walking 10,000 steps if health is key. Track with an app for momentum.

- **Days 15-21: Assault Mode** – Launch attacks: confront one fear head-on, like asking for a raise or ending a toxic friendship. Celebrate with a ritual, perhaps a Vodou-inspired gratitude dance or just blasting uplifting music.

- **Days 22-28: Consolidation** – Secure gains: review progress, adjust tactics. If a goal slips, analyze like Dessalines post-battle— what worked, what didn’t? Reinforce with positive affirmations drawn from rebel quotes.

- **Days 29-30: Independence Declaration** – Reflect on transformations. Write a “proclamation” of your new freedoms and share with your allies. Plan quarterly check-ins to maintain liberty.

Vertières reminds us that empires fall when the oppressed rise with heart and strategy. You’re not just reading history—you’re living it. So, grab that saber (metaphorically), charge forward, and claim your victory. The world needs more revolutionaries like you.