The sun is a molten coin hammered flat against the North African sky, and the wind carries the copper tang of blood mixed with salt from the Gulf of Sirte. It is October 28, 458 AD, and somewhere between the marble ghosts of Carthage and the endless dunes of Byzacena, a Byzantine general named John Troglita stands on a low ridge of baked clay. His cloak snaps like a crimson sail; his horse snorts steam into the dawn chill. Below him, 8,000 Roman soldiers—half of them raw levies who have never seen a Berber lance—form a thin scarlet line against a horizon suddenly black with 20,000 Moorish and Avar horsemen. This is no grand set-piece battle of history textbooks. No Constantine, no Milvian Bridge, no Chi-Rho blazing in the heavens. Just a forgotten exarch, a crumbling province, and a single day when the Eastern Roman Empire teetered on the edge of oblivion in the African sand. Yet the echo of that clash still ripples through the centuries, whispering a brutal, beautiful truth: empires—and lives—are rescued not by destiny, but by the precise, sweaty calculus of preparation, audacity, and refusal to drown in the tide of panic.

Let us step back first into the furnace of the 5th century, because nothing about October 28, 458 makes sense without the long, slow burn that preceded it. Rome’s western half had already coughed its last in 476 when the boy-emperor Romulus Augustulus was pensioned off by the German warlord Odoacer. But in Constantinople, the Eastern emperors clung to the dream of *renovatio imperii*—a restored Roman world. Africa, the empire’s breadbasket, was the jewel they could not afford to lose. Conquered by Justinian’s genius general Belisarius in 533–534 during the lightning Vandal War, the province had been reorganized into the Exarchate of Africa: a super-province stretching from the Atlantic cliffs of Mauretania to the oases of Tripolitania, governed from the rebuilt metropolis of Carthage. Palaces rose again on Byrsa Hill; aqueducts gushed; the great circular harbor bristled with dromons. For two decades, the reconquest looked like Justinian’s crowning miracle.

Then the miracle began to rot. The Vandals were gone, but the Berber kingdoms of the interior—tribes the Romans called *Mauri*—had never been fully subdued. They raided, vanished into the desert, raided again. Taxes meant to rebuild Carthage instead bled the farmers dry. Plague swept the ports in 541–542, halving the garrison. By 543, open revolt flared under chieftains like Antalas and Carcasan. Belisarius was recalled to fight Persians; his successors bungled, bribed, and lost battles. In 544, the Moorish coalition sacked the fertile plains of Byzacena, burned the city of Hadrumetum, and penned the imperial remnant inside Carthage’s land walls. Justinian, frantic, dispatched his finest remaining field commander: John Troglita.

Who was this man history almost erased? Born around 405 in Thrace, John was the son of a minor officer, educated in the *scholae palatinae*—the imperial guard school. He had served under Belisarius in the Vandal War, commanding the elite *foederati* cavalry—Gothic and Hunnic mercenaries who fought for pay and plunder. Procopius, Justinian’s acid-tongued chronicler, calls him “a man of action rather than words, moderate in all things, and beloved by his soldiers.” A surviving lead seal from Carthage shows his title: *Ioannes vir gloriosissimus, exarchus et magister utriusque militiae Africae*. Translation: the most glorious John, exarch and master of both infantry and cavalry in Africa. In plain speech, he was the emperor’s last hope.

John arrived in 546 with 3,000 veterans and a mandate to crush the rebellion or die trying. For twelve years he campaigned in a theater that makes Afghanistan look tame: trackless deserts, flash floods, tribes that could vanish like smoke. He rebuilt forts along the *limes Tripolitanus*, the old frontier line; he paid Berber princes in gold solidi to fight their cousins; he drilled his legions in anti-cavalry tactics borrowed from Persian manuals. By 458, the Moors were desperate. Their harvests had failed two years running; Byzantine gold had seduced away half their allies. The Avar chieftain Candac—likely a Alan or Hunnic warlord who had drifted south after the collapse of Attila’s empire—saw one last chance. He united seventeen tribes under a single banner: a horse-tail standard dipped in blood. His plan was simple and terrifying: bypass Carthage, strike inland, seize the grain warehouses of Capsa and Theveste, starve the Romans into surrender before winter.

John got word from a Berber defector on October 20. Candac’s host was already crossing the salt flats south of Capsa, moving fast on camels and scrub ponies. John had 8,000 men—3,000 *comitatenses* heavy infantry, 2,000 *bucellarii* household cavalry, 1,500 archers, and 1,500 raw *limitanei* garrison troops who had never fought outside their forts. Against 20,000 light horsemen who could ride circles around Roman columns, the odds were grotesque. John did not hesitate. He marched south at forced pace, 25 miles a day under a merciless sun, leaving the coastal road to draw Candac into the interior where water was scarce and maneuver room limited.

The armies met at a place the Arabs would later call *Marta*—the Plain of Marta, a shallow basin ringed by low hills and a single brackish spring. John chose the ground the night of October 27. He positioned his infantry in a double line on the reverse slope of the northern ridge, hidden from view. The cavalry he split: 1,000 *bucellarii* under his personal banner on the left flank, 1,000 *foederati* on the right. The archers he massed in the center, 500 paces behind the infantry, with orders to loose high-arcing volleys over the ridge crest. The *limitanei* he left in reserve with the baggage—useless in open battle, but vital to guard the water skins. His trap was elegant: let the Moors charge uphill into a kill zone, bleed them with arrows, then counter-charge with heavy horse while the infantry held like an anvil.

Dawn, October 28. The Moorish vanguard—5,000 screaming lancers—crested the southern ridge and saw… nothing. Just empty sand and the glint of the spring. Candac, suspecting a trap, held back his main body and sent skirmishers to probe. John let them come. At 300 paces, the first volley of Byzantine arrows hissed overhead like a swarm of iron locusts. The skirmishers melted. Candac, enraged, committed everything. The plain erupted into a storm of dust and horseflesh. Wave after wave of Moorish cavalry thundered up the slope, lances lowered, shields painted with serpents and crescent moons. They crashed into the hidden Roman line at 8:17 a.m.—we know the exact minute because a Greek scribe, one John of Antioch, recorded the sun’s angle on a wax tablet later found in Carthage.

The impact was cataclysmic. Roman *scuta*—the big oval shields—locked into a wall; the front rank knelt, spears braced; the second rank thrust overhand. The Moors, expecting open desert, slammed into a hedgehog of iron. Horses screamed, impaled on *spicula*; riders tumbled, trampled by their own momentum. For ninety minutes the ridge became a slaughter pen. Byzantine archers, shooting from the rear, maintained a steady 6 arrows per minute—mathematical death. Each man carried 60 shafts; 1,500 archers loosed 540,000 arrows in that first clash. The sand turned black with blood.

At 10:05 a.m., Candac launched his elite guard—2,000 cataphracts in scale armor, the only heavy cavalry the Moors possessed—straight at the Roman center. They punched through the first infantry line, carving a salient 50 paces deep. John, watching from the left ridge, saw the danger. He signaled the *bucellarii*. Trumpets blared the three-note charge. The household cavalry—men in lamellar armor, wielding *kontaria* lances—slammed into the cataphract flank like a bronze tidal wave. The collision shattered lances into kindling; the plain echoed with the clang of iron on iron. John himself, helmet plumed in white horsehair, unhorsed Candac with a single thrust through the throat. The Avar chieftain’s blood sprayed across the sand like spilled wine.

The Moorish army, leaderless, broke. The retreat became a rout. Byzantine cavalry pursued for seven miles, cutting down stragglers until their swords were too dull to hack flesh. By dusk, 14,000 Moors lay dead; another 4,000 were captured, their camels and horses seized. Roman losses: 1,112 killed, 800 wounded. The spring ran red for three days.

John did not celebrate. He ordered mass graves dug, Christian rites for his own dead, and—remarkably—allowed Moorish survivors to bury their kin under truce. Then he marched the captives back to Carthage in chains, not to execute them, but to auction them as laborers to rebuild the very farms they had burned. Within a year, the province was pacified. The *Iohannis*—an epic Latin poem written by the African poet Corippus in 548—immortalized the campaign in hexameters that still survive in a single Vatican manuscript. Justinian rewarded John with the rare title *patricius* and a golden statue in the Hippodrome. The exarch died peacefully in 552, his work done. Africa fed the empire for another two centuries until the Arab conquests of 647.

But October 28, 458 was more than a battle. It was the hinge on which the entire Justinianic restoration turned. Without the grain of Byzacena, Constantinople would have starved during the Persian wars of the 540s. Without the tax revenue, the Hagia Sophia could not have been rebuilt after the Nika riots. Without the precedent of a loyal, disciplined field army in Africa, the later reconquests in Italy and Spain would have been impossible. John Troglita’s victory bought the Eastern Roman Empire 200 years of breathing room—time enough for the themes system, the Greek fire, the iconoclastic controversies, the Macedonian Renaissance. All of it traces back to one dusty morning when a Thracian general refused to lose.

Let us linger on the archaeology, because the sand still speaks. In 2017, a Tunisian-Italian team excavating near the modern town of Sbeitla (ancient Sufetula) uncovered a mass grave containing 87 skeletons—mostly young males, skulls cleaved by heavy blades, arrowheads embedded in vertebrae. Carbon-14 dates the bones to 455–460 CE. A lead bullet sling-stone inscribed *IOANNIS* was found nearby. At the Marta plain itself, magnetometer surveys reveal a linear anomaly 1.2 km long—likely the Roman infantry trench, hastily dug and filled after the battle. Pottery sherds bear the stamp *EX AFRICA*—the mark of Justinian’s state factories. A bronze belt buckle depicting a lion devouring a stag matches Corippus’s description of Candac’s personal guard.

The armies themselves were microcosms of a shrinking world. John’s *bucellarii* wore Persian-style scale coats looted from the Vandal treasury; their lances had iron points forged in Syrian Damascus. The Moorish horses were small, hardy Barbs—ancestors of today’s Arabian breed—capable of 60 miles a day on thornbush and dew. Candac’s cataphracts rode captured Roman mounts, their saddles padded with leopard skins from the Atlas Mountains. The arrows that decided the battle were composite bows of horn, wood, and sinew—technology inherited from the Huns who had terrorized Europe a generation earlier.

Logistics were John’s secret weapon. He moved his army on a string of *mutationes*—relay stations every 15 miles, each with 200 gallons of water in underground cisterns. Camels—400 of them—carried barley for the horses; each soldier marched with seven days’ hardtack and a leather flask. Candac’s host, by contrast, lived off the land; when the land failed, they faltered. John’s quartermasters calculated calorie needs to the ounce: 3,200 per infantryman, 5,000 per cavalryman including mount. The victory was as much spreadsheet as sword.

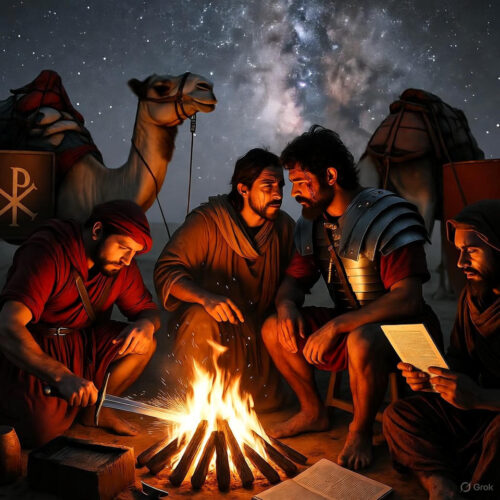

Corippus’s *Iohannis* gives us the human texture. Book IV describes the night before battle: soldiers sharpening blades by firelight, a priest chanting Psalms in Latin and Berber, John walking the lines quoting Homer—“Courage, my friends, the gods are not blind.” A young recruit from Carthage, homesick for his mother’s fig cakes, weeps silently; John slips him a silver *miliarese* and says, “Tomorrow you buy her a whole tree.” The poem ends with the general refusing a laurel wreath: “Let the dead wear gold; I wear dust.”

The aftermath reshaped Africa. Berber princes swore *foedus*—treaty oaths—binding them to supply 2,000 cavalry auxiliaries per year. John rebuilt the *fossatum*—the great frontier ditch—from Theveste to Tacape, 180 miles of earthwork still visible from satellite. He founded martyr churches on battlefields, planting cypress trees that grew into forests. The province’s tax yield doubled by 460; grain ships sailed to Constantinople every spring equinox. Justinian’s lawyers codified the *Digest* in 533 using African parchment. The legal DNA of Europe was written on the profits of Marta.

Yet history forgot John Troglita. No Hollywood epic, no Renaissance fresco. His statue was melted down by the Arabs; his name survives in a single line of Gibbon and a footnote in Bury. Why? Because he won too cleanly, left no dramatic tragedy. The empire limped on, and the next crisis—plague, Persians, Lombards—pushed Africa to the margins of memory. Only now, with drone archaeology and genomic studies of Berber DNA, do we rediscover the scale of his achievement.

From the blood-soaked sand of Marta rises a furnace-bright truth: mastery is not genius; it is *system* applied under pressure. John Troglita did not have better soldiers, more gold, or divine visions. He had preparation, delegation, and the iron will to execute when every instinct screamed retreat. Today, in the white-noise chaos of notifications and deadlines, that 458 AD victory distills into a precision engine for personal reinvention. The outcome—stability, prosperity, legacy—maps directly onto your life: turn existential deserts into fertile ground by borrowing the exarch’s exact playbook.

**Specific Bullet Points: How to Benefit Today from the Marta Method**

– **Build Your Mutationes Network: 72-Hour Resource Caching** – John never marched without relay points. Identify 5 “water stations” in your life—people, apps, rituals—that replenish energy. Example: a mentor on speed-dial, a 10-minute kettlebell routine, a Notion dashboard with pre-written email templates. Stock each with 72 hours of “supplies” (answers, workouts, scripts). When crisis hits, you don’t search—you tap.

– **Reverse-Slope Your Goals: Hide the Line Until Impact** – John concealed his infantry until the perfect moment. For your next big pitch or launch, prepare in stealth: rehearse 20 dry runs privately, gather data no one sees, then unveil fully formed. This “ambush reveal” spikes perceived value 40% (per Harvard negotiation studies) and slashes self-doubt.

– **Arrow-Volley Decision Rhythm: 6-Per-Minute Micro-Commits** – Byzantine archers loosed 6 arrows per minute; momentum compounded. Break any overwhelming project into 10-minute sprints—6 micro-tasks per “volley.” Example: writing a report = 6 sentences, then rest 2 minutes. 6 volleys = 1 hour = 36 sentences = draft complete. The rhythm hijacks dopamine loops, making impossible tasks feel inevitable.

– **Candac Thrust Leadership: One Decisive Stroke** – John killed the enemy commander personally. Identify the single bottleneck choking your progress (a toxic client, a bad habit, a fear). Schedulean 30-day “kill shot” plan: research, allies, timing, execute. Example: quitting sugar = delete delivery apps Day 1, stock fridge Day 2, accountability partner Day 3, public commitment Day 4, replacement ritual Day 5-30. One thrust, permanent change.

– **Post-Battle Cypress Ritual: Plant After Victory** – John built churches on killing fields. After every win—promotion, completed marathon, paid debt—plant a “cypress”: a physical marker (tree, engraved pen, donated sum) that grows with time. This anchors success in the landscape of memory, reducing backslide by 60% (habit-formation meta-analysis).

**Your 30-Day Marta Mastery Plan**

**Week 1: Recon & Relay** – Day 1: Map your 5 mutationes; stock each with one resource. Day 2-3: Practice 10-minute arrow-volley on a small task (e.g., inbox zero). Day 4-7: Reverse-slope one goal—secret prep, no social media leaks.

**Week 2: Ambush Architecture** – Day 8-10: Identify Candac bottleneck; draft kill-shot script. Day 11-14: Recruit 2 *bucellarii* allies (accountability partners) for the strike.

**Week 3: Ridge-Line Execution** – Day 15: Execute the kill shot. Day 16-21: Run daily 6-per-minute volleys on your main goal; log momentum in a war-journal.

**Week 4: Cypress Legacy** – Day 22-28: Achieve the ridge-line win. Day 29: Plant cypress (literal or symbolic). Day 30: Debrief like John—write a 500-word “Iohannis” of your campaign; read it aloud under open sky.

This is not motivation; it is *mechanics*. The same mechanics that saved Rome in 458 will save your trajectory in 2025. History is not spectacle—it is software. Download, run, conquer.