Imagine a world where the throne of one of history’s greatest empires is claimed not by a mighty warrior or a royal heir, but by a woman who started as a lowly concubine. On October 16, 690, in the grand halls of Luoyang, Wu Zetian did just that, proclaiming herself emperor of China and founding the Wu Zhou dynasty. This wasn’t just a power grab; it was a seismic shift in a society bound by Confucian traditions that relegated women to the shadows. Wu Zetian’s story is a tapestry of cunning strategy, relentless determination, and bold innovation, set against the backdrop of the Tang dynasty’s golden age. As we delve into this distant chapter from over 1,300 years ago, we’ll uncover the intricate details of her life, her path to power, and the profound impact of her reign. But beyond the history, we’ll explore how her audacious spirit can inspire us today to shatter our own glass ceilings and forge paths of personal success.

Wu Zetian’s ascension wasn’t an overnight miracle but the culmination of decades of maneuvering in a cutthroat imperial court. Born in 624 during the early years of the Tang dynasty, she entered a world teeming with political upheaval. The Tang had risen from the ashes of the Sui dynasty’s collapse, under the leadership of Emperor Gaozu and his son Emperor Taizong, who expanded China’s borders and fostered a cultural renaissance. Yet, beneath the prosperity lurked fierce rivalries among nobles, eunuchs, and imperial family members. Wu, originally named Wu Zhao, hailed from a merchant family in Wenshui County, Shanxi province. Her father, Wu Shihuo, had supported Li Yuan (Gaozu) in his rebellion against the Sui, earning him positions as a chancellor and governor. This connection thrust the family into the elite circles, allowing young Wu an education uncommon for girls of the era—she studied history, literature, politics, and even Buddhist texts, honing a sharp intellect that would become her greatest weapon.

At the tender age of 14, in 638, Wu was selected to join Emperor Taizong’s harem as a cairen, a fifth-grade concubine. The palace was a labyrinth of luxury and danger, where thousands of women vied for the emperor’s favor. Taizong, known for his military prowess and administrative reforms, nicknamed her “Meiniang” or “Charming Lady.” Historical accounts from the Old Book of Tang describe her as beautiful, eloquent, and fearless. One anecdote highlights her boldness: when Taizong’s unruly horse, the Lion Stallion, proved untamable, Wu suggested using an iron whip to lash it, then a hammer to strike its head if needed, and finally a dagger to slit its throat. Impressed, Taizong praised her courage, but she bore him no children, limiting her influence.

Upon Taizong’s death in 649, childless concubines were customarily sent to Buddhist monasteries to live as nuns. Wu entered Ganye Temple in Chang’an, shaving her head and adopting monastic life. But fate—or perhaps her own scheming—intervened. Taizong’s son, Li Zhi, who became Emperor Gaozong, had noticed Wu during his father’s reign. On the first anniversary of Taizong’s death, Gaozong visited the temple, and their encounter reignited a forbidden romance. Gaozong’s court was already fractured: his empress, Wang, was childless and jealous of Consort Xiao, who had borne a son. In a twist of irony, Empress Wang, hoping to distract Gaozong from Xiao, arranged for Wu to return to the palace in 651, allowing her hair to grow back. Wu re-entered as a zhaoyi, the highest second-rank concubine, and swiftly became Gaozong’s favorite.

From here, Wu’s ascent accelerated amid a storm of intrigue. In 652, she gave birth to her first son, Li Hong, followed by Li Xian in 653. But palace politics turned deadly. In 654, Wu bore a daughter who died mysteriously shortly after birth. Wu accused Empress Wang of murder, claiming she had visited the child’s room. Whether this was truth, accident, or Wu’s own orchestration remains debated among historians, but it sealed Wang’s fate. Gaozong, smitten with Wu, sought to depose Wang, but faced opposition from conservative chancellors like Chu Suiliang, who argued it violated filial piety since Wu had served his father. Undeterred, Wu built alliances with officials like Xu Jingzong and Li Yifu. By late 655, accusations of witchcraft against Wang and her mother led to their demotion. On November 1, 655, Wu was installed as empress, a position from which she would wield unprecedented power.

As empress, Wu transformed from consort to co-ruler. Gaozong’s health deteriorated around 660, plagued by dizziness, headaches, and vision loss—possibly hypertension or a stroke. Wu stepped in, reviewing memorials and issuing edicts from behind a screen during audiences, earning the duo the nickname “The Two Sages.” She reorganized the harem with a mix of benevolence and iron-fisted control, promoting loyalists and demoting threats. In 656, she orchestrated the deposition of Crown Prince Li Zhong, Gaozong’s son by another consort, installing her own Li Hong as heir. Opponents were systematically eliminated: in 659, Chancellor Zhangsun Wuji, Taizong’s brother-in-law and a pillar of the old guard, was accused of treason and forced to commit suicide in exile. Chu Suiliang, exiled earlier, died in disgrace, his family scattered.

Wu’s family also rose: her mother was titled Lady of Rongguo, and nephews like Wu Chengsi gained titles. But tensions simmered. Wu’s half-brothers, resentful of past slights, were exiled and died mysteriously. In 664, a brief rift with Gaozong arose when he considered deposing her over sorcery accusations, but Wu’s plea and quick counter-accusations led to the execution of the plotters, including Chancellor Shangguan Yi. This solidified her dominance. By 670, with Gaozong increasingly incapacitated, Wu handled state affairs, including military campaigns against the Western Turks and Tibetans. She promoted Buddhism, funding statues at Longmen Grottoes and associating herself with Maitreya prophecies to legitimize her authority.

Tragedy—or calculated moves—struck her sons. In 675, Li Hong, who had urged mercy for imprisoned princesses, died suddenly, rumored poisoned by Wu. Li Xian succeeded him but fell out of favor amid rumors of illegitimate birth; in 680, he was deposed for treason and forced to suicide in exile. Li Zhe (later Zhongzong) became crown prince. Wu’s secret police, led by figures like Zhou Xing and Lai Junchen, enforced loyalty through torture and false confessions, creating an atmosphere of terror.

Gaozong’s death on December 27, 683, marked Wu’s full emergence. Li Zhe ascended as Zhongzong, but Wu, as empress dowager, assumed regency. Zhongzong’s attempts to favor his wife’s family led to his swift deposition in February 684; he was exiled, and Wu installed her youngest son, Li Dan (Ruizong), as a puppet emperor. She moved the capital to Luoyang, away from Chang’an’s Tang loyalists, and renamed it “Divine Capital.” Rebellions erupted: in 684, Li Jingye raised an army in Yangzhou, proclaiming restoration of the Tang, but was crushed. Wu executed sympathizers, including Pei Yan, a chancellor who suggested ceding power.

The regency years saw Wu consolidate through propaganda and purges. She elevated her Wu ancestors to imperial status, built grand shrines, and claimed divine omens. In 688, princes of the Li family rebelled in fear of extermination; Wu suppressed them brutally, executing dozens of relatives and officials. Buddhist monks like Xue Huaiyi, her alleged lover, propagated her as the reincarnated Maitreya. She introduced new characters into the Chinese script, including one for her name, Zhao, meaning “sun and moon illuminating the sky.”

By 690, the stage was set for her unprecedented move. Opposition was silenced, and petitions from officials urged her to take the throne. On September 9, 690, at the newly constructed Mingtang—a colossal hall symbolizing heavenly mandate—she received auspicious signs. Finally, on October 16, 690 (Gengchen day in the lunar calendar), Wu Zetian ascended, declaring the Wu Zhou dynasty and adopting the title “Holy and Divine Emperor.” She changed the era name to Tianshou (“Heaven Bestowed”) and granted amnesty. Ruizong was demoted to heir apparent and given the Wu surname. This act interrupted the Tang for 15 years, reviving the ancient Zhou name to evoke legitimacy, as the original Zhou (1046–256 BCE) was seen as a model of virtue.

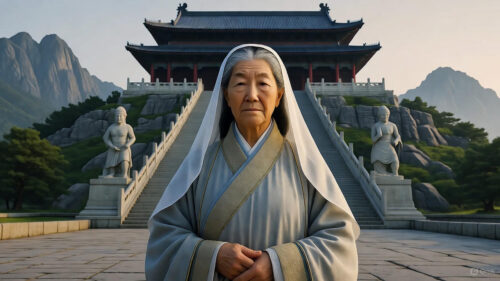

The ascension ceremony in Luoyang was a spectacle of grandeur. Wu, then 66, donned imperial robes traditionally reserved for men, complete with the mianguan crown. Thousands of officials, monks, and foreign envoys attended, witnessing her proclamation from the throne. She justified her rule through Buddhist scriptures and omens, like a “precious chart” from the Luo River prophesying a female ruler. This wasn’t mere theater; it challenged millennia of patriarchal norms, drawing on precedents like the Han’s Empress Lü but surpassing them by claiming the emperor title outright.

Wu’s reign from 690 to 705 was a blend of prosperity and paranoia. She centralized power, reforming the bureaucracy to favor merit over birthright. The imperial examination system was expanded, allowing commoners to rise—officials like Di Renjie, a brilliant administrator, were promoted despite initial opposition to her. Economically, she implemented the equal-field system more rigorously, distributing land to peasants and reducing taxes during famines. Agricultural output soared, with innovations in irrigation and crop rotation.

Militarily, Wu maintained Tang expansions. In 692, her armies defeated Tibetan invaders, securing the Silk Road. She received tribute from Korea, Japan, and Central Asian states, fostering diplomatic ties. In 697, she recalled general Wang Xiaojie to crush a Khitan rebellion. Culturally, Wu patronized the arts: she commissioned the translation of Sanskrit sutras, built temples like the White Horse Monastery, and supported poets and scholars. The Longmen Grottoes flourished with her funding, featuring massive Buddha statues symbolizing her divine rule.

Yet, her policies weren’t without innovation. She created the “copper box” system for anonymous petitions, encouraging public input on governance. Women gained slightly more rights; she honored female scholars and allowed widows greater autonomy. In foreign affairs, she sent envoys to India and Persia, importing technologies like sugar refining.

Controversies shadowed her achievements. Wu’s secret police continued their reign of terror, executing thousands on flimsy charges. In 697, Chancellor Wei Yuanzhong was nearly killed but spared after proving innocence. Her favoritism toward lovers like the Zhang brothers—young, handsome officials—sparked scandals, with rumors of debauchery in her later years. Nepotism was rampant: nephews Wu Sansi and Wu Chengsi plotted to succeed her, leading to court factions.

Health failing by 700, Wu grew isolated, relying on the Zhangs. In 705, at 81, a coup by loyalists like Zhang Jianzhi forced her abdication on February 20. Zhongzong was restored, ending the Wu Zhou on March 3. Wu died on December 16, 705, and was buried with Gaozong in Qianling Mausoleum, her blank stele symbolizing either humility or the historians’ refusal to praise her.

Wu Zetian’s legacy is polarizing. Confucian historians like Sima Guang in the Zizhi Tongjian vilified her as a tyrant, emphasizing her ruthlessness and “unnatural” rule. Yet, she stabilized the empire, paving the way for the Tang’s high point under Xuanzong. Modern scholars view her as a feminist icon, breaking barriers in a male-dominated world. Her reign saw population growth to 50 million, economic booms, and cultural exchanges that enriched China.

In distant history, Wu Zetian’s story on October 16, 690, stands as a testament to human ambition’s power to reshape empires. But what if we applied her lessons to our lives today? Her journey from obscurity to sovereignty offers profound insights for personal growth. By emulating her strategic mindset, resilience, and innovative spirit, anyone can overcome obstacles and achieve greatness.

– **Cultivate Strategic Alliances:** Just as Wu built networks with key officials like Xu Jingzong, identify mentors and collaborators in your career. For instance, join professional groups or LinkedIn networks to connect with influencers who can open doors.

– **Pursue Lifelong Learning:** Wu’s early education fueled her rise; commit to daily reading or online courses in your field, such as a 30-minute Duolingo session for language skills or Coursera modules on leadership.

– **Embrace Bold Risks:** Her ascension required defying norms; in your life, take calculated risks like applying for a promotion you’re underqualified for, preparing with mock interviews and skill-building workshops.

– **Build Resilience Against Setbacks:** Wu survived exiles and plots; develop a routine like journaling three gratitudes daily to reframe failures, or practice mindfulness apps to handle stress.

– **Innovate and Adapt:** She reformed systems for merit; in personal finances, adopt budgeting tools like YNAB to optimize spending, or in health, experiment with new workouts tracked via apps.

A step-by-step plan to apply Wu’s legacy: Week 1: Assess your current “court”—list strengths, weaknesses, and allies. Week 2: Set an ambitious goal, like a career shift, and research paths. Week 3: Take action, such as networking events or skill courses. Week 4: Review progress, adjust for obstacles, and celebrate small wins. Repeat monthly, channeling Wu’s tenacity to transform your life into an empire of achievement.