Imagine a city on the brink, its ancient walls trembling under the thunder of an invading horde that had toppled kingdoms like dominoes. On October 15, 1529, the fate of Europe hung by a thread as the mighty Ottoman Empire, led by the legendary Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, finally lifted its siege on Vienna after weeks of brutal warfare. This wasn’t just a battle; it was a clash of civilizations, a test of human endurance against overwhelming odds. What started as a grand Ottoman campaign to dominate Central Europe ended in a muddy, rain-soaked retreat, marking a turning point that reshaped the continent’s history. Dive into this epic tale, where clever defenses, relentless weather, and sheer grit turned the tide. It’s a story packed with intrigue, heroism, and unexpected twists that make history feel like a blockbuster thriller. And by the end, we’ll uncover how this distant event can supercharge your life today—because if a outnumbered band of defenders could repel an empire, imagine what you can achieve against your own “sieges.”

To set the stage, we need to travel back to the vibrant yet volatile world of the early 16th century. The Ottoman Empire was at its zenith, a sprawling superpower stretching from the gates of Persia to the shores of North Africa and deep into the Balkans. Founded in the late 13th century by Osman I, a Turkish warrior whose descendants would forge one of history’s most enduring dynasties, the Ottomans had mastered the art of conquest. By the 1400s, they had captured Constantinople in 1453 under Mehmed II, renaming it Istanbul and ending the Byzantine Empire’s thousand-year run. This victory wasn’t just military; it was symbolic, blending Islamic traditions with Byzantine administration, creating a multicultural juggernaut that tolerated diverse religions under the millet system while extracting tribute and loyalty.

Enter Suleiman I, who ascended the throne in 1520 at the age of 26. Known as “the Magnificent” in the West for his grandeur and “the Lawgiver” in his empire for reforming legal codes, Suleiman was a Renaissance man in a turban. He was a poet, a patron of the arts—commissioning stunning mosques like the Süleymaniye in Istanbul designed by the architect Sinan—and a strategist who expanded the empire’s navy under Barbarossa, the infamous admiral who terrorized Mediterranean seas. Under Suleiman, the Ottomans reached their territorial peak, controlling key trade routes that funneled spices, silks, and gold from Asia to Europe. His army was a marvel: janissaries, elite infantry recruited from Christian boys converted to Islam and trained rigorously; sipahis, feudal cavalry rewarded with land grants; and akinjis, irregular raiders who struck fear like medieval shock troops. By 1529, Suleiman’s forces had already crushed the Safavids at Chaldiran in 1514 and the Mamluks in Egypt in 1517, adding vast wealth and prestige.

But Europe was the ultimate prize. The Holy Roman Empire, a patchwork of principalities under Charles V, was distracted by wars with France and the Protestant Reformation sparked by Martin Luther in 1517. Charles, who ruled Spain, the Netherlands, and Austria, was Suleiman’s archrival, both claiming universal monarchy—one Christian, one Muslim. The spark for the 1529 campaign ignited in Hungary, a buffer state ripe for exploitation. In 1521, Suleiman had captured Belgrade, the “key to Hungary,” after a grueling siege where Ottoman sappers tunneled under walls and janissaries stormed breaches amid cannon fire. This opened the Danube route, a vital artery for invasion.

The real catalyst came in 1526 at the Battle of Mohács. King Louis II of Hungary, a young and inexperienced ruler married to Habsburg princess Mary, mustered about 25,000 troops—knights in gleaming armor, Hungarian magnates with their retainers, and Croatian allies. Facing them was Suleiman’s army of 50,000 to 100,000, bolstered by artillery innovations like chained cannons that fired grapeshot. On August 29, 1526, near the Danube in southern Hungary, the battle unfolded in a swampy plain. Louis charged prematurely, his heavy cavalry bogged down in mud as Ottoman artillery decimated them. Janissaries formed wagon forts, pouring volley fire from muskets. In just two hours, 14,000 Hungarians lay dead, including Louis, who drowned fleeing across a stream—his horse slipping, or perhaps struck by debris. Seven bishops and 500 nobles perished, gutting Hungary’s leadership. Suleiman, ever the showman, had the battlefield cleared but left enemy heads piled as grim warnings. He occupied Buda briefly but withdrew, leaving chaos.

This vacuum triggered a succession crisis. Archduke Ferdinand I, Charles V’s brother and Louis’s brother-in-law, claimed the throne via marriage pacts, securing western Hungary at the Diet of Pozsony. But John Zápolya, a Transylvanian voivode with local support, crowned himself king and appealed to Suleiman for aid, offering vassalage. Suleiman, seeing a chance to weaken the Habsburgs, backed Zápolya. Ferdinand struck first, capturing Buda in 1527 with German mercenaries, but Ottoman counterattacks in 1528 reversed gains. By early 1529, Ferdinand’s aggression threatened Zápolya, prompting Suleiman to intervene decisively. Historians debate Suleiman’s intent: Was Vienna the goal, or a bonus after securing Hungary? Some argue it was to impose Ottoman suzerainty over all Hungary; others see it as a stepping stone to Germany. Either way, it was ambitious—Vienna was 400 miles from Istanbul, across hostile terrain.

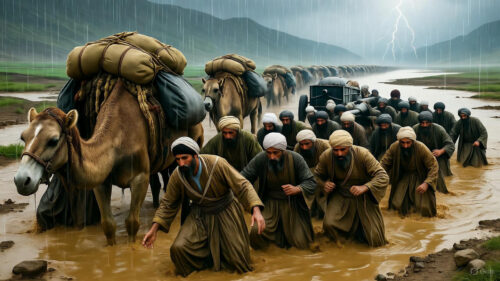

Suleiman’s preparations were meticulous. In April 1529, he named Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha as serasker, granting him sultan-like powers. The army assembled in Bulgaria: estimates range from 120,000 to 300,000, including 6,000 janissaries, 12,000 sipahis, Moldavian contingents, and Serbian renegades. Artillery included 300 cannons, some massive bombards capable of hurling 700-pound stones. Camels carried supplies from Syria, horses from Anatolia. The campaign launched on May 10 from Edirne, but nature conspired against them. Torrential spring rains turned Balkan roads into quagmires. Rivers flooded, bridges collapsed. Heavy artillery sank in mud; Suleiman abandoned most large guns, a fatal decision for siege work. Camels, unused to cold and wet, died by thousands. Disease spread—dysentery, perhaps plague—thinning janissary ranks. The march took three months instead of one.

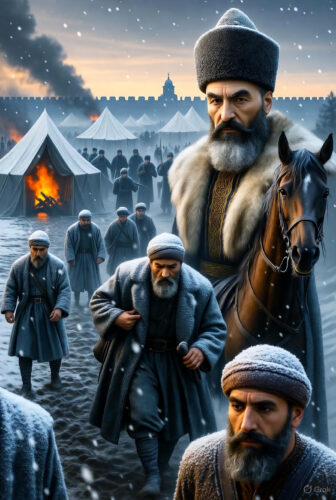

By August 6, Suleiman reached Osijek, then Mohács on August 18, where Zápolya’s 10,000 cavalry joined, swelling forces. They recaptured lost fortresses: Buda fell September 8 after minimal resistance, its garrison massacred. En route, only Pozsony (Bratislava) resisted, bombarding the Ottoman fleet on the Danube. As news spread, panic gripped Vienna. Queen Mary fled to Linz, but civilians rallied. Ferdinand appealed for aid; Charles V sent Spanish harquebusiers, while German princes dispatched Landsknechts. By late September, Suleiman’s army, now around 100,000 effective, encamped outside Vienna. But they were exhausted, short on supplies, and without heavy siege tools. The stage was set for an epic standoff.

Vienna in 1529 was no fortress metropolis. Its walls, dating to the 13th century, were thin—some only six feet thick—and outdated against gunpowder. The city housed 80,000 inhabitants, but many fled, leaving 17,000-21,000 defenders: 16,000 regulars including 1,000 Landsknechts under Niklas Graf Salm, a 70-year-old veteran of Pavia; 700-800 Spanish harquebusiers; 2,000 Serbian hussars under Pavle Bakić; and 5,000 militia. Wilhelm von Roggendorf oversaw logistics, but Salm commanded operations from St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Preparations were frantic: gates blocked, walls reinforced with earth bastions, inner ramparts built, suburbs razed for clear fire lines. Trap pits and palisades dotted approaches. Spanish marksmen patrolled the Danube banks, sniping at Ottoman scouts.

Suleiman offered terms: surrender for mercy. Three Austrian envoys in finery were sent back unanswered; Salm reciprocated with Muslim captives. The siege began September 27. Ottomans, lacking heavy artillery, relied on mining—sappers dug tunnels under walls to plant explosives. Janissaries assaulted breaches, but defenders countered fiercely. Sorties disrupted diggers; on October 6, 8,000 Austrians attacked tunnels, destroying many but losing heavily in close quarters. Rain continued, flooding trenches, turning camps into swamps. Ottoman assaults on October 9 and 12 were repelled by pikes and gunfire—harquebus volleys mowing down waves.

By October 11, more rain fell, morale plummeted. Janissaries grumbled; supplies dwindled. Suleiman held a council October 12: one final push on October 14, with bonuses for first over the walls. Thousands charged, but defenders held, their long pikes skewering climbers, arquebuses blazing. Casualties mounted—Ottomans lost thousands, defenders 1,500 dead. On October 15, with snow flurrying unusually early, Suleiman ordered retreat. Tents burned, prisoners slaughtered to avoid slowing the march. The siege, lasting 18 days, ended.

The retreat was hellish. Muddy roads, Austrian harassment—Katzianer and Bakić’s cavalry killed 200, freed captives. Ottomans scorched earth, pillaging Styria, enslaving 20,000. They reached Buda October 26, Constantinople December 16. Atrocities marred the campaign: “Sackmen” raiders murdered, raped, enslaved civilians, even ripping babies from wombs per eyewitness Peter Stern von Labach.

Significance? The siege halted Ottoman advance, exposing logistical limits—no more deep European thrusts until 1683. It bolstered Habsburg prestige, reconciling Charles V and Pope Clement VII, leading to Charles’s 1530 coronation. For Ottomans, it was spun as victory—ceremonies in Istanbul celebrated. Suleiman tried again in 1532 but stalled at Kőszeg, defended by 800 Croats under Nikola Jurišić. Hungary remained divided until 1699. Salm died of wounds in 1530; his monument stands in Vienna’s Votivkirche. Maximilian II built Neugebäude Castle on Suleiman’s tent site.

This tale of defiance isn’t just dusty history—it’s a blueprint for triumph. The Viennese faced an empire with ingenuity, unity, and unyielding spirit. Today, channel that in your life: when challenges besiege you, fortify your resolve.

– **Build Your Defenses Early:** Like Salm reinforcing walls, identify weaknesses in your career or health. For example, if job insecurity looms, upskill via online courses in AI or coding—dedicate 10 hours weekly to platforms like Coursera.

– **Assemble a Diverse Team:** Vienna’s mix of Spaniards, Germans, and Serbs won the day. In your projects, collaborate with varied perspectives—join networking groups on LinkedIn, aiming for one new connection weekly from different fields.

– **Counterattack Strategically:** Sorties disrupted Ottomans; in life, tackle problems head-on but smartly. Facing debt? Create a budget app plan, cutting non-essentials by 20% monthly while side-hustling on Upwork for extra income.

– **Endure the Elements:** Rain doomed Suleiman—adapt to setbacks. If a fitness goal falters due to illness, switch to home yoga via YouTube, tracking progress in a journal for motivation.

– **Know When to Pivot:** Suleiman’s retreat saved his army; recognize when to shift goals. If a relationship strains, seek counseling sessions bi-weekly instead of forcing ahead.

The Plan: Week 1: Assess your “siege”—list top challenges. Week 2: Fortify defenses with specific actions (e.g., resume updates). Week 3: Rally allies—schedule meetups. Week 4: Execute countermeasures, tracking wins. Monthly: Review and adjust, celebrating small victories like the Viennese did. Embrace this history-fueled mindset—you’re unbreakable!