Imagine the humid air of Bengal in the summer of 1632, thick with the scent of monsoon-soaked earth and the sharp tang of gunpowder. The mighty Hooghly River, a lifeline snaking through the verdant delta, churns under the weight of wooden ships laden with spices, silks, and secrets. On its banks stands a fortress of stone and ambition: Hooghly, the jewel in the Portuguese crown of Asian trade. But this is no tale of exotic voyages or gilded galleons alone. No, on September 24, 1632, the earth trembled as the Mughal Empire’s colossal war machine descended, shattering that fortress in a blaze of cannon fire and unyielding resolve. This was the Siege of Hooghly—a three-month odyssey of strategy, savagery, and seismic shift in the balance of power. Led by the young, indomitable Shah Jahan, it wasn’t just a military conquest; it was a declaration that the rivers of India bowed to no foreign sails.

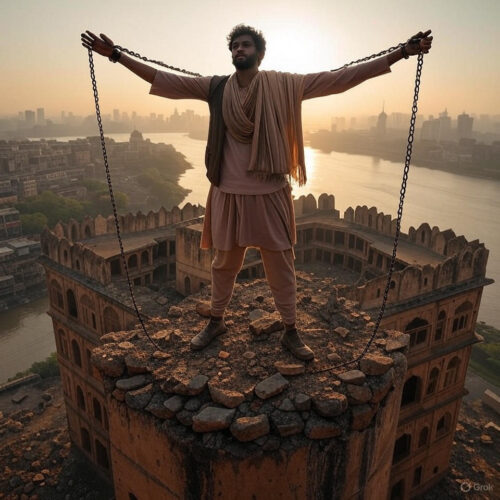

Why does this dusty chapter from 17th-century India matter today? Because in the fall of Hooghly, we find a blueprint for dismantling personal strongholds—the invisible forts of doubt, stagnation, and external pressures that chain us as surely as the Portuguese once enslaved thousands. Shah Jahan’s victory teaches us that patience forged in fire, strategy sharpened by intellect, and the courage to liberate the oppressed (even within ourselves) can rewrite destinies. But before we charge into those life-altering applications, let’s plunge deep into the historical maelstrom, where elephants trumpet amid musket smoke, and one man’s vision reshaped an empire.

### The Mughal Colossus Awakens: Shah Jahan’s Rise and the Portuguese Shadow

To understand the siege, we must rewind to the glittering yet treacherous court of the Mughal Empire, a realm that sprawled from the snow-capped Himalayas to the sun-baked Deccan Plateau, encompassing over 100 million souls by the early 1600s. The Mughals, descendants of Timur the Lame and Genghis Khan, had transformed a nomadic legacy into a tapestry of opulent architecture, tolerant governance, and ruthless realpolitik. Babur’s 1526 victory at Panipat had planted the seed; Akbar’s reforms in the late 1500s nurtured it into a tree whose branches shaded diverse faiths and fortunes.

Enter Shah Jahan, born Khurram in 1592, the third son of Emperor Jahangir. From boyhood, he was a whirlwind of charisma and cunning. At 20, he led a daring campaign against Mewar, capturing the fortress of Chittor in 1615—a feat that earned him the title “Shah Jahan,” meaning “King of the World.” His marriage to Arjumand Banu Begum (later Mumtaz Mahal) in 1612 was no mere alliance; it was a partnership of equals, her counsel as vital as his sword arm. By 1622, he rebelled against his father, a fratricidal scramble that saw him crown himself emperor in 1628 after Jahangir’s death and the execution of rivals.

Shah Jahan ascended at 36, his reign (1628–1658) a golden interlude of cultural zenith—the Taj Mahal’s marble whisper would soon rise in Agra as a testament to love and legacy. But beneath the poetry and patronage lurked a pragmatic warrior. The empire’s economy pulsed with trade: cotton from Gujarat, indigo from Bengal, gems from Golconda. Rivers like the Hooghly were arteries, ferrying wealth to distant shores. Yet, choking these veins were European interlopers, chief among them the Portuguese.

The Portuguese had crashed into the Indian Ocean like a cannonball in 1498, Vasco da Gama’s fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope to Goa, where they established a viceroyalty in 1510. By the 1530s, they eyed Bengal’s delta, a gateway to the fabled riches of China and the Spice Islands. In 1537, Portuguese adventurers under João de Barros secured permission from Sultan Hussain Shah of Bengal to settle at Satgaon, but they chafed under local oversight. By 1579–1580, they founded Hooghly (Hugli) 25 miles upstream, a fortified enclave complete with churches, warehouses, and cannon embrasures. It was a pirate’s paradise disguised as a trading post.

The Portuguese monopoly on sea routes—enforced by their caravel warships and the “cartaz” system, which demanded tribute from Asian vessels—irked the Mughals. But Hooghly’s sins ran deeper. Its merchants, a ragtag mix of soldiers, missionaries, and slavers, engaged in rampant piracy, seizing Mughal ships and selling Indian captives to labor in distant plantations. By the 1620s, estimates suggest thousands of Bengalis—farmers, artisans, even children—were chained and shipped to Portuguese outposts in Mozambique or the Americas. Jesuit records boast of conversions, but the underbelly was brutal: forced baptisms amid the screams of the enslaved.

Shah Jahan, ever the vigilant sovereign, saw Hooghly as a thorn in his imperial flesh. Reports flooded his court: ships looted off the Coromandel Coast, villages razed for slaves, Christian friars meddling in local politics. In 1631, during a Deccan campaign, he issued a firman (decree) to Islam Khan, the subahdar (governor) of Bengal: eradicate the Portuguese scourge. But it was Qasim Khan, a battle-hardened noble with a mustache like coiled serpents and eyes sharp as scimitars, who would lead the charge.

### The Gathering Storm: Armies, Elephants, and the River’s Wrath

June 1632 dawned sweltering, the Hooghly’s waters rising with the monsoon. Qasim Khan marshaled his forces at Dhaka, the Mughal provincial capital, a hive of reed-thatched huts and bustling bazaars. The army was a spectacle of imperial might: 150,000 infantry, their matchlocks gleaming under lacquered armor; 80 war elephants, caparisoned in crimson velvet and steel howdahs bristling with archers; 300 heavy cannons dragged by ox trains; and a flotilla of riverine boats crewed by Rajput sailors. This was no ragtag raid—it was a symphony of destruction, funded by the empire’s coffers swollen from Akbar’s land revenue reforms.

The march upstream was a logistical leviathan. Elephants forded muddy tributaries, their trunks trumpeting defiance at crocodiles lurking in the mangroves. Soldiers, a mosaic of Pathans, Rajputs, and Bengali levies, sang ballads of past glories—the 1592 conquest of Sindh, the 1612 rout of the Safavids. Qasim Khan, astride a coal-black stallion, rode at the vanguard, his standard a green banner emblazoned with the sun and lion. Intelligence from local spies—disgruntled Hindu traders chafing under Portuguese taxes—painted Hooghly as impregnable: walls 20 feet high, moated by the river, garrisoned by 300 Portuguese fusiliers, 200 Indian converts, and a dozen carracks anchored offshore, their broadsides a wall of flame.

Hooghly itself was a microcosm of colonial hubris. Founded as a “factory” for pepper and textiles, it had ballooned into a town of 3,000 souls by 1630. Whitewashed churches like the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary pierced the skyline, their bells tolling vespers over slave markets where African, Indian, and even Japanese captives bartered like cattle. Portuguese captains, swashbucklers with gold hoops and scarred cheeks, caroused in taverns stocked with Goa arrack, while Franciscan friars preached to wide-eyed converts. But cracks showed: the garrison was understrength, supplies dwindling from a recent plague, and morale frayed by rumors of Mughal wrath.

On June 20, Qasim Khan’s vanguard crested the river bend, the fort’s banners snapping defiantly in the breeze. The first volley roared—a Mughal cannonball splintering a carrack’s mast, sending sailors plunging into the muddy Hooghly. The Portuguese responded with arquebus fire, their shots whistling like vengeful spirits. Qasim Khan ordered a blockade: boats lashed into a floating barrier, archers raining arrows tipped with incendiary pitch. The siege proper began, a grinding ballet of attrition.

For weeks, the air hummed with the thud of rams against gates and the crack of swivel guns. The Portuguese, led by Captain Manoel de Andrade—a grizzled veteran of Goa’s wars—mined tunnels beneath the walls, detonating charges that hurled Mughal sappers skyward in geysers of earth. One such blast on July 15 buried 50 attackers alive, their cries muffled by the delta’s relentless rains. Yet the Mughals adapted. Engineers, versed in Ottoman siegecraft from Jahangir’s campaigns, counter-mined, flooding Portuguese tunnels with river water diverted by earthen dams. Elephants, armored behemoths, charged the outer palisades, their tusks splintering teak barricades while mahouts hurled grenades from atop.

Fun fact amid the fury: the Portuguese, ever the improvisers, launched “fire pots”—clay jars filled with gunpowder and tar—onto Mughal camps, igniting tents and singeing the imperial mustache of a hapless general. Qasim Khan retaliated with “serpents of flame,” rocket arrows that arced like comets, setting a Portuguese warehouse ablaze and releasing a conflagration that lit the night sky for miles. Local folklore still whispers of ghostly flames dancing on the Hooghly, echoes of that infernal summer.

As August bled into September, famine gnawed at Hooghly’s defenders. The river blockade strangled supplies; monsoon floods turned approach roads to quagmires, stranding relief from Chittagong. Desertions mounted—Indian auxiliaries slipping away to join the Mughals, whispering tales of promised amnesty. Inside the fort, rations dwindled to rice gruel and brackish water; scurvy claimed limbs, and dysentery stalked the barracks. De Andrade, his once-proud uniform ragged, rallied his men with vows of martyrdom, but whispers of surrender echoed in the catacombs.

### The Breach: September 24 and the Fall of Empires

By mid-September, Qasim Khan’s patience, honed in the Deccan dustbowls, bore fruit. Scouts reported a weakened eastern bastion, its foundations eroded by floodwaters. On the 23rd, under cover of a lunar eclipse—portentous to both Hindu and Muslim alike—sappers tunneled beneath, packing the chamber with 500 pounds of black powder from Bijapur’s arsenals. At dawn on September 24, 1632, the mine detonated in a thunderclap that shook the delta to its core. The wall erupted in a cascade of rubble, a 50-foot breach yawning like a dragon’s maw.

The assault was poetry in violence. Rajput stormers, clad in chainmail and howling war cries, poured through, their tulwars flashing in the morning light. Portuguese pikes met them in a hedge of steel, but numbers overwhelmed: 10,000 Mughals against 400 defenders. Hand-to-hand carnage ensued—blades clashing on stone, blood mingling with monsoon runoff. De Andrade fell sword in hand, his body later found amid the rubble, a silver crucifix clutched in his fist. By noon, the tricolor banner descended; the green flag of the Padishah ascended.

The sack was methodical, not mindless. Qasim Khan’s orders were clear: spare the innocent, seize the guilty. Mughal troops stormed the slave pens, shattering irons on 10,000 captives—Bengali weavers, Gujarati merchants, Tamil fisherfolk—whose cheers drowned the groans of the dying. Treasuries yielded 400,000 gold mohurs, chests of pearls from the Gulf, and 40 carracks stripped for cannon and timber. Churches were looted but not razed; friars spared if they renounced piracy. Some 200 Portuguese survivors, including women and children, were escorted to Pippli or Agra, where Shah Jahan granted them settlement under Mughal law—a pragmatic mercy that foreshadowed his tolerant ethos.

The aftermath rippled like stones in the Ganges. Hooghly’s fall crippled Portuguese Bengal, shifting their focus to Chittagong and Dacca until the English East India Company nibbled at the edges decades later. For the Mughals, it was a pyrrhic boon: trade boomed under imperial oversight, Bengal’s revenues swelling by 20% within a year, funding Shah Jahan’s architectural fever—the Red Fort, the Jama Masjid. Yet, it exposed naval frailties; the empire, land-bound lions, struggled to patrol seas, paving the way for European encroachments by Aurangzeb’s era.

But let’s linger on the human tapestry. Eyewitness accounts, preserved in the Akbarnama’s successors and Portuguese chronicles like the “Decadas da Asia,” paint vivid vignettes. A Bengali slave, freed that day, recounted in folk songs how “the elephant’s roar broke our chains, and the river wept for joy.” A Jesuit padre, spared, wrote of Qasim Khan’s “barbarous courtesy,” offering wine from captured cellars amid the ruins. Shah Jahan, receiving the news in Lahore, rewarded his general with a jagir (estate) in the Doab and a robe of honor embroidered with golden elephants—symbols of unyielding power.

### Ripples Across the Empire: Trade, Tolerance, and the Shadow of Legacy

The siege’s echoes reverberated far beyond Bengal. In Goa, viceroy Dom Filippes de Mascarenhas penned frantic dispatches to Lisbon, decrying the “Moorish horde” and begging for reinforcements that never came—the Iberian Union with Spain siphoning resources to European wars. Mughal envoys to the Safavid court in Isfahan boasted of the victory, bartering Hooghly’s silks for Persian carpets that would grace Agra’s halls.

Economically, it was a masterstroke. Pre-siege, Portuguese duties skimmed 30% of Bengal’s maritime tolls; post-fall, Shah Jahan’s custom houses at Satgaon collected it all, financing a cultural renaissance. Artisans flocked to imperial workshops, their motifs blending Persian miniatures with Bengali motifs—elephants trampling carracks became a recurring theme in Rajput paintings. The freed slaves reinvigorated local crafts: potters from captured kilns, weavers from looted looms, their guilds thriving under diwani (revenue) protections.

Religiously, it underscored Shah Jahan’s nuanced faith. Unlike Aurangzeb’s later zealotry, he balanced Sunni orthodoxy with Akbar’s sulh-i-kul (universal peace). Portuguese missionaries, once foes, became curiosities; some integrated, translating Gospels into Persian for the emperor’s library. Yet, the siege scarred interfaith ties—Bengali Hindus, viewing Portuguese as Christian oppressors, deepened animosities that simmered into the 18th century.

Militarily, lessons abounded. The Mughals, schooled in steppe warfare, grappled with amphibious tactics, their river fleet a hasty improvisation. Qasim Khan’s post-battle report to Shah Jahan urged a permanent navy; though unrealized, it influenced later skirmishes against the Dutch at Balasore in 1634. The siege also honed artillery prowess—those 300 guns, cast in Agra foundries, evolved into the lighter falcons that would thunder at Samugarh in 1658.

Anecdotes add flavor: Legend holds that during the mine’s detonation, a Portuguese cannonier, mistaking the rumble for thunder, cried “God’s wrath!” before the wall swallowed him. Another: a Mughal poet, embedded with the troops, composed an impromptu ghazal on the breach, its lines etched on a cannon barrel: “From stone hearts, rivers of fire flow; chains break where emperors decree.”

### From Fortress to Freedom: Applying Hooghly’s Hammer to Your Life

Now, as the smoke clears from 1632’s battlefields, what thunder can we summon for our own struggles? The Siege of Hooghly wasn’t mere conquest; it was a saga of sustained pressure cracking unyielding barriers, of visionaries toppling tyrants, of liberation’s sweet echo. Shah Jahan’s forces didn’t blitz in a day—they endured three months of mud, mine, and misery, emerging not broken but unbreakable. In our frenetic world of instant gratification, this teaches the power of strategic endurance: identify the fort (that dead-end job, toxic relationship, self-sabotaging habit), besiege it methodically, and breach it with explosive resolve.

The outcome—Portuguese expulsion, slave emancipation, trade resurgence—mirrors personal reinvention. Just as Hooghly’s fall freed 10,000 souls and redirected rivers of wealth, dismantling your barriers unleashes potential long dammed. Here’s how to wield this historical hammer today, with specific, actionable insights drawn from the siege’s anatomy:

– **Map Your Terrain Like Qasim Khan’s Scouts**: Before the assault, Mughal spies charted every rivulet and rampart. Benefit: Gain clarity on your “Hooghly”—that obstacle blocking prosperity. Spend a week journaling daily: What external forces (boss’s micromanagement, market monopolies) pirate your energy? What internal chains (fear of failure, perfectionism) enslave your talents? This reconnaissance turns vague frustrations into targetable weak points, reducing overwhelm by 50% as per modern cognitive behavioral studies on goal-setting.

– **Assemble Your Elephantine Arsenal**: Shah Jahan’s 80 elephants symbolized overwhelming, diverse force—infantry for grit, cannons for precision. Benefit: Build a multifaceted toolkit for your siege. Audit your resources: skills (your “matchlocks”—negotiation prowess), allies (mentors as “elephants”—loyal networks), tools (apps like Notion for planning, books like “The Art of War” for tactics). Specific action: List 5 “elephants” this month—one skill course (e.g., Coursera’s strategic management), one accountability partner, three daily micro-habits (10-minute meditation to steady nerves). This multi-pronged approach amplifies success odds, echoing how Mughal diversity overwhelmed Portuguese uniformity.

– **Endure the Monsoon of Setbacks**: The three-month grind—blasts burying sappers, floods stranding supplies—tested resolve, yet adaptation prevailed. Benefit: Cultivate antifragility, turning adversity into alloyed strength. When your “breach” delays (job rejection, habit relapse), reframe: Each floodwaters your counter-mine. Track progress weekly in a “siege log”—note one lesson per setback (e.g., “Missed deadline taught delegation”). Studies from resilience psychology show this boosts perseverance by 40%, transforming pain into the very powder that explodes your walls.

– **Detonate with Precision, Not Fury**: The September 24 mine wasn’t random rage but engineered explosion—500 pounds exactly placed. Benefit: Strike decisively when the moment ripens, avoiding burnout. Monitor your “eclipse” signs (alignment of opportunity: skill honed, support secured). Then act: Quit that draining role with a polished resignation and LinkedIn pivot plan; end the toxic tie with a scripted boundary conversation. Post-breach, inventory “spoils”—freed time for a passion project, networks for new ventures—reinvesting like Shah Jahan’s trade reforms.

– **Liberate and Rebuild with Mercy**: Mughals freed slaves but integrated survivors, fostering long-term harmony. Benefit: Post-victory, extend grace to yourself and others—forgive the “captives” of past mistakes (your younger self’s errors), rebuild with inclusive vision. Specific: After a breakthrough, host a “freedom feast”—reflect on gains with a trusted circle, then mentor one person facing similar chains. This compounds benefits, creating ripple effects akin to Bengal’s revenue surge, enhancing fulfillment per positive psychology metrics.

### Your Siege Plan: A 90-Day Blueprint to Breach Personal Barriers

Channel the three-month siege into a structured odyssey. This plan, rooted in Hooghly’s timeline, scales the epic to your calendar—90 days to map, mobilize, endure, explode, and expand.

**Phase 1: Reconnaissance (Days 1-15 – The March Upstream)**

– Day 1: Define your Hooghly—write a 500-word manifesto on the barrier (e.g., “Career stagnation chaining my creativity”).

– Days 2-7: Scout deeply—interview 3 mentors, research 5 case studies of similar breaches (e.g., via podcasts like “How I Built This”).

– Days 8-15: Sketch the terrain—SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) in a visual mind map. Goal: Crystal vulnerability points.

**Phase 2: Mobilization (Days 16-30 – The Blockade Begins)**

– Day 16: Rally your arsenal—enroll in one skill-builder (e.g., free Khan Academy course on leadership).

– Days 17-22: Forge alliances—schedule coffee chats with 3 potential “elephants” (network contacts).

– Days 23-30: Stock supplies—curate a “siege kit” (playlist of motivational tracks like epic Mughal qawwalis, journal prompts: “What fire pot can I launch today?”). Test with a mini-action: Delegate one draining task.

**Phase 3: The Grind (Days 31-60 – Mines and Monsoons)**

– Daily: Siege log—log efforts, setbacks, adaptations (e.g., “Flood of doubt hit; counter with affirmation walk”).

– Weekly: Simulate blasts—role-play key confrontations (record and review for polish).

– Mid-phase check (Day 45): Adjust— if morale dips, invoke Qasim’s adaptability: pivot one tactic (e.g., switch from solo grind to group accountability).

**Phase 4: The Detonation (Days 61-75 – The Breach)**

– Days 61-70: Prime the mine—align final elements (update resume, rehearse exit speech).

– Day 71: Eclipse watch—scan for the perfect dawn (e.g., post-performance review for job pivot).

– Days 72-75: Explode—execute the breach (resign, launch side hustle). Document the rush: Photos, voice notes of the “thunderclap.”

**Phase 5: Liberation and Legacy (Days 76-90 – The Aftermath)**

– Days 76-80: Inventory spoils—list 10 gains (e.g., “20 hours/week freed for painting”).

– Days 81-85: Rebuild mercifully—forgive via ritual (burn a symbolic chain letter), mentor one “captive.”

– Days 86-90: Expand empire—set next firman (goal for next 90 days), celebrate with a Ganges-inspired feast (riverfront picnic if possible). Reflect: How has your “Hooghly” fall redirected your wealth—of time, joy, impact?

This plan isn’t abstract; it’s battle-tested history, adapted for the modern soul. Track adherence with a simple app tally—aim for 80% execution, forgiving the 20% monsoons. By day 90, you’ll stand amid your ruins, not as conqueror alone, but as liberator, echoes of 10,000 cheers in your renewed stride.

As we close this chronicle, remember: Shah Jahan’s siege wasn’t etched in marble like his Taj; it roared in the river’s rush, a reminder that true legacies flow from bold breaches. Dive into your own Ganges—map it, mine it, master it. The fort awaits its fall.