On September 17, 1862, the rolling hills and cornfields near Sharpsburg, Maryland, became a theater of unimaginable human drama. The Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American history, unfolded amid the golden hues of early autumn, where the clash of blue and gray uniforms painted the landscape in shades of sacrifice and strategy. This wasn’t just a skirmish between armies; it was a pivotal moment in the American Civil War, a crossroads where the fate of a divided nation hung in the balance. As Confederate General Robert E. Lee pushed his Army of Northern Virginia into Union territory for the first time, seeking to shift the war’s momentum, Union Major General George B. McClellan scrambled to halt the invasion. What followed was a day of ferocious combat, tactical blunders, and raw courage that left over 22,000 men killed, wounded, or missing. Yet, from this carnage emerged a strategic victory for the North, paving the way for President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and altering the course of history.

To understand the depth of Antietam, we must delve into the intricate web of events leading up to that fateful morning. The Civil War had raged for over a year by 1862, with the Confederacy holding its own through brilliant maneuvers and defensive tenacity. Lee’s recent triumph at the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August had emboldened the South. With Virginia’s resources strained—farms barren from constant foraging and morale dipping—Lee saw an opportunity in Maryland. The state was a borderland, teeming with Southern sympathizers, and invading it could rally support, disrupt Union supply lines, and perhaps even draw Britain and France into the fray by demonstrating Confederate strength on Northern soil.

On September 3, Lee’s army, numbering around 55,000 battle-hardened troops, crossed the Potomac River into Maryland. They marched under orders to live off the land, but the reception was cooler than anticipated. Marylanders, influenced by Union occupation and abolitionist sentiments, offered little aid. Lee’s Special Order 191, a detailed plan dividing his forces to capture Harpers Ferry and other strategic points, was issued on September 9. This document outlined detachments: Stonewall Jackson to seize Harpers Ferry, while the rest of the army under James Longstreet would screen movements. It was a bold gamble, dispersing troops across a wide front to achieve multiple objectives.

Fate, however, favored the Union in an almost comedic twist. On September 13, near Frederick, Maryland, Union soldiers from the 27th Indiana Infantry discovered three cigars wrapped in a crumpled copy of Special Order 191, discarded by careless Confederates—possibly from D.H. Hill’s division. The find reached McClellan’s headquarters that evening. Here was Lee’s entire playbook: dates, routes, and objectives laid bare. McClellan, ever the cautious commander, exclaimed, “Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.” Yet, despite this windfall, McClellan dithered. His Army of the Potomac, swollen to 87,000 men through reinforcements, could have crushed Lee’s divided forces. Instead, delays plagued the pursuit, allowing Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry on September 15, netting 12,000 prisoners and 73 cannons—a boon for the South.

As Union forces closed in, preliminary clashes erupted. On September 14, the Battle of South Mountain tested Lee’s lines at Turner’s, Fox’s, and Crampton’s Gaps. McClellan’s aggressive push forced Lee to consolidate, but it bought precious time. By evening on September 16, Lee had reformed his army along Antietam Creek, a shallow stream winding through undulating farmland. The terrain favored defense: high bluffs on the Confederate side, the Hagerstown Turnpike bisecting the field, and natural barriers like the creek, woods, and fences. Lee’s left flank anchored near the Dunker Church, a plain white building owned by German Baptist Brethren; the center featured the infamous Sunken Road; and the right was protected by the bridge over Antietam Creek, soon to bear Ambrose Burnside’s name.

McClellan arrived that afternoon, surveying the field from a hilltop. His plan was methodical: a three-pronged assault. Joseph Hooker’s I Corps would strike Lee’s left at dawn, supported by Edwin V. Sumner’s II Corps and Joseph K.F. Mansfield’s XII Corps. In the center, the V and VI Corps under Fitz John Porter and William B. Franklin would hold. On the right, Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps would cross the bridge to envelop Lee’s flank—a diversionary feint, in McClellan’s mind, though it became anything but. Artillery would soften targets, and coordination was key. But McClellan, haunted by fears of Lee’s superior numbers (he estimated 120,000 Confederates), held back reserves, a decision that would haunt the battle’s legacy.

Dawn broke foggy on September 17, around 5:30 a.m., with the crack of rifle fire shattering the quiet. Hooker’s corps, 8,600 strong, advanced through the East Woods toward David Miller’s 40-acre cornfield, a sea of tall stalks hiding Confederate pickets from John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade. The Cornfield became a charnel house. Union artillery from the Poffenberger Heights raked the field, but as Hooker’s men—Irish immigrants from the 63rd New York and others—pushed forward, they met withering volleys. The corn “ran red with blood,” as one survivor recalled, stalks shredded by Minié balls. By 6 a.m., the 11th Corps under Mansfield joined, but confusion reigned; Mansfield himself was shot by friendly fire while rallying troops, dying hours later.

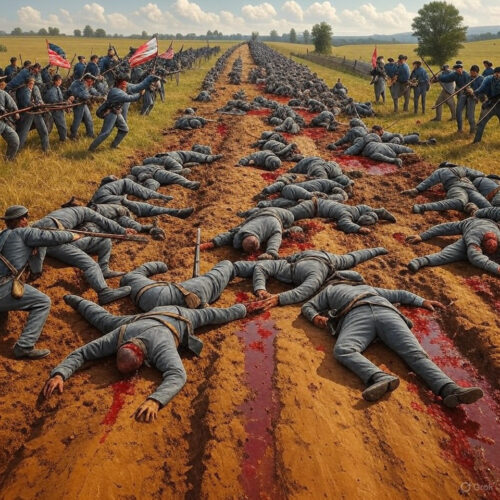

The fighting intensified. Hood’s men, roused from slumber in the West Woods, counterattacked ferociously. “Those damned red flags!” a Union soldier shouted, referring to the Confederate banners. The field changed hands 15 times in 90 minutes, with regiments like the Louisiana Tigers losing 323 of 500 men. By 9 a.m., as Hooker withdrew, the Cornfield was a tableau of horror: bodies twisted amid trampled corn, the air thick with powder smoke and the cries of the wounded. The Dunker Church, mere yards away, became a focal point, its white walls splattered with blood as artillery shells exploded nearby.

Sumner’s II Corps arrived around 8 a.m., with French’s division veering left into the chaos. Sedgwick’s division pushed into the West Woods, but Stonewall Jackson’s corps, reinforced by fresh brigades, flanked them in a devastating enfilade. Hundreds fell in minutes; Sedgwick’s men, packed in parade-ground formation, were mowed down. “It was a slaughter pen,” wrote one officer. By 10 a.m., the Union morning offensive stalled, with over 5,000 casualties on Hooker’s and Sumner’s fronts alone. McClellan, observing from afar, sent no reinforcements, citing the need to preserve his army.

The midday phase shifted to the center, where the Sunken Road—a farm lane worn deep by wagon traffic—offered Confederates under D.H. Hill a perfect defensive position. Around 9:30 a.m., Richard French’s division of Sumner’s corps advanced, supported by Israel’s Richardson. The road, held by Georgia and Maryland troops, bristled with rifles. Union assaults were repulsed with heavy losses, but persistence paid off. By noon, a shift in the Confederate line—caused by a misunderstood order—exposed the flank. Union troops poured in, turning the road into a death trap. Bodies piled four deep; the lane earned its moniker, Bloody Lane. Richardson was mortally wounded, and French captured hundreds, but again, McClellan refrained from exploiting the breach, fearing a Confederate counterstroke.

As the sun climbed higher, the afternoon’s drama unfolded on the southern end. Burnside’s IX Corps, delayed by morning fog and terrain, faced the stone bridge over Antietam Creek—guarded by just 500 Georgians under Robert Toombs on the heights above. Multiple assaults failed: the first at 10 a.m. saw men gunned down in the open; the second routed. Not until 1 p.m., after heroic charges by the 51st New York and 51st Pennsylvania—wading the creek upstream to flank—did they seize the bridge by 1 p.m., at the cost of 500 lives. Burnside’s men pressed up the hill toward Sharpsburg, threatening Lee’s escape route.

But Lee’s genius shone through. At 2:30 p.m., A.P. Hill’s division, 2,500 men marching 17 miles from Harpers Ferry since dawn, arrived dusty and exhausted. Spotting Burnside’s advance, Hill hurled them into the fray without pause. The counterattack smashed the Union line, killing hundreds and halting the envelopment. By 5:30 p.m., as shadows lengthened, both sides disengaged, the fields silent save for the moans of the dying.

September 18 brought a tense standoff. Lee, outnumbered two-to-one, prepared for renewal, but McClellan, satisfied with “victory,” launched no assault. Under a flag of truce for the wounded, Lee slipped away that night, crossing the Potomac with his army intact. The toll was staggering: Union losses 12,410 (2,108 dead); Confederate 10,316 (1,546 dead). Antietam National Battlefield today preserves 8,000 acres, with monuments to the fallen, including the iconic Bloody Lane observation tower.

The battle’s aftermath rippled far beyond Maryland. Tactically a draw, strategically it was a Union triumph—the first major check on Lee’s invasion. Northern morale soared; European powers withheld recognition. Most crucially, on September 22, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, framing the war as a fight against slavery, effective January 1, 1863, for areas in rebellion. This transformed the conflict’s moral dimension, deterring foreign intervention and bolstering enlistment.

Delve deeper into the human stories, and Antietam’s tapestry grows richer. Take Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the future Supreme Court justice, shot through the chest while charging the Cornfield. He survived, later quipping, “I should have been proud of the wound if it had been in a better cause.” Or Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross, who braved the lines to aid the wounded, her wagon the first to reach the field post-battle. Confederate surgeon Jonathan Letterman revolutionized medical care with triage systems tested here. Even the landscape bore witness: farmer David Miller lost his cornfield and barn to fire from artillery.

Photographer Alexander Gardner arrived days later, capturing haunting images—the dead of the 20th Massachusetts at the Cornfield, their faces frozen in eternal repose. These photos, published in the New York Times, shocked the nation, humanizing the war’s brutality. Lee’s gamble failed, but his audacity inspired; McClellan’s caution cost him command by November, replaced by the aggressive Ambrose Burnside—who ironically led the disastrous Fredericksburg assault in December.

Antietam’s significance endures in military annals. It highlighted the rifled musket’s dominance, making frontal assaults suicidal against entrenched foes. Tactics evolved toward maneuver and artillery. Politically, it unified the North behind emancipation, shifting from preserving the Union to destroying slavery. Economically, the battle strained both sides: the Confederacy’s invasion yielded little plunder, while the Union poured resources into recovery.

Years later, veterans reunited at the field, North and South, reconciling over shared graves. The 50th anniversary in 1912 drew 50,000, with President Taft dedicating monuments. Today, the site hosts living history events, where reenactors in wool uniforms march the same paths, evoking the era’s tension.

To grasp the prelude’s complexity, consider the Seven Days Battles in late June 1862, where McClellan nearly captured Richmond but retreated after heavy losses. This Peninsula Campaign failure prompted Lincoln to reorganize the Army of Virginia under John Pope, leading to Second Bull Run’s debacle. Lee’s subsequent Maryland thrust was opportunistic, timed with Braxton Bragg’s Kentucky invasion to stretch Union defenses.

Special Order 191’s loss remains a mystery. Historians debate if it was intentional disinformation or mere sloppiness. Copies were distributed widely—Lee kept none, a procedural lapse. McClellan’s delay? Paranoia from prior intelligence failures, or perhaps reluctance to risk his beloved army. On September 14 at South Mountain, Union victories at Crampton’s Gap (under William Franklin) nearly trapped 3,000 Confederates, but Franklin halted short of Pleasant Valley, allowing their escape—a microcosm of McClellan’s hesitancy.

The battle’s phases warrant granular examination. In the Cornfield, Hooker’s 12-pound Napoleon guns fired 1,800 rounds in 30 minutes, a barrage rivaling Gettysburg’s. The Irish Brigade, chanting the Litany of the Saints, charged with green flags aloft, losing 540 of 1,200. Hood’s Texans, fighting without breakfast, held for hours before relief, their brigadier remarking, “The men have given their last drop of blood for this cause.”

Mansfield’s death at 8:15 a.m. decapitated XII Corps; Alpheus Williams assumed command amid chaos. Sumner’s advance into the West Woods saw the 34th New York decimated—252 casualties from 400. The Roulette Farm became a command post, its yard a makeshift hospital.

Bloody Lane’s drama peaked around 12:30 p.m. when Colonel John B. Gordon of the 6th Alabama was shot five times, the last through the cheek, yet he rallied his men before fainting in a pile of dead. Union breakthroughs faltered as artillery from Porter’s reserves—held back—failed to support. Franklin, observing, called it “a butchery.”

Burnside’s Bridge, a 12-foot-wide span, saw three failed assaults costing 500 lives for 100 Confederate casualties. The flanking maneuver by Colonel Hugh Ewing’s men, fording waist-deep water under fire, exemplifies small-unit initiative. A.P. Hill’s arrival—his men in blue pants captured at Harpers Ferry—confused Union lines briefly, but their ferocity turned the tide. Hill himself was grazed by bullets, later noting, “My division went in with a cheer and came out with a cheer.”

Post-battle, burial details were grim. Locals and soldiers interred the dead in shallow graves; many Confederates were unidentified, buried in mass trenches. The creek ran red for days, staining mill wheels downstream. Disease followed: typhoid and dysentery claimed more lives than bullets in the aftermath.

Lincoln’s visit on October 1 was tense. McClellan hosted him at the Pry House, but the president’s frustration boiled over. “If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time,” Lincoln later confided. The Emancipation Proclamation’s issuance was no whim; drafts dated to July, but Antietam provided the “victory” needed to avoid perceptions of desperation.

In broader context, Antietam influenced global perceptions. British Prime Minister Palmerston, eyeing intervention, deemed the battle a stalemate but Lincoln’s proclamation a moral pivot. French Emperor Napoleon III, sympathetic to the South, wavered. Domestically, Copperhead Democrats decried the “butcher’s bill,” but Republican resolve hardened.

Military lessons abound. The battle validated the importance of interior lines—Lee’s ability to shift troops rapidly. It exposed McClellan’s flaws: overestimation of foes, underutilization of intelligence. Burnside’s delay stemmed from fragmented command; Reno’s death at South Mountain left him in nominal charge without full authority.

Archaeology at Antietam yields artifacts: bullets, bayonets, and buttons unearthed annually, preserving the site’s integrity. The 1962 centennial saw congressional acts expanding the park, now managed by the National Park Service.

Veterans’ accounts add color. Union Private Elisha Hunt Rhodes wrote in his diary: “The roar of battle was incessant… I saw men fall dead all around.” Confederate General John B. Hood lamented, “My poor old division… melted away.” These narratives humanize the statistics, revealing fear, camaraderie, and conviction.

Antietam’s legacy extends to civil rights. The Emancipation Proclamation, while limited (freeing slaves only in rebel states), set the stage for the 13th Amendment. It inspired Frederick Douglass, who praised Lincoln’s boldness. Modern scholars debate its military impact—did it prolong the war by alienating border states?—but its ethical weight is undeniable.

Consider the role of cavalry. J.E.B. Stuart’s horsemen screened Lee’s movements, skirmishing at Crampton’s Gap, but were absent during the main battle, focused on reconnaissance. Artillery duels were pivotal; Union batteries on high ground outgunned Confederates, who had only 250 guns to the North’s 300.

Weather played a part: the fog delayed Burnside, while a brief rain on the 16th muddied roads. Logistically, Lee’s army subsisted on green corn and apples, weakening them; McClellan’s men, well-supplied, marched on full rations.

International observers noted the battle’s ferocity. Prussian Captain Justus Scheibert, embedded with Lee, marveled at the “iron storm” in the Cornfield, later influencing European tactics. British Colonel Garnet Wolseley praised Lee’s defensive genius.

In literature, Antietam echoes in works like Stephen Crane’s *The Red Badge of Courage*, inspired by Civil War tales, and Shelby Foote’s *The Civil War: A Narrative*, which details the battle’s minutiae.

Preservation efforts continue: the Antietam Battlefield Alliance raises funds for land acquisition, ensuring the “hallowed ground” remains untouched. Annual commemorations include lantern tours of Bloody Lane, where guides recount ghostly sightings—perhaps the spirits of the fallen.

As the sun set on September 17, 1862, the fields fell quiet, but the echoes reverberated. Antietam wasn’t just a battle; it was a forge, tempering the nation’s resolve amid blood and fire.

## Applying Antietam’s Lessons to Your Life Today

The outcome of Antietam—a tactical stalemate that became a strategic turning point through perseverance, timely adaptation, and moral clarity—offers profound benefits for individuals navigating modern challenges. Lee’s audacity in the face of odds, McClellan’s use of intelligence (despite flaws), and the soldiers’ unyielding grit demonstrate how historical resilience can fuel personal growth. By embracing these principles, you can turn personal “battles”—career setbacks, health struggles, or relational conflicts—into opportunities for victory.

– **Harness Intelligence Like McClellan**: Just as Special Order 191 provided a roadmap, gather and act on information in your life. Research job markets before switching careers; use apps to track health metrics. Benefit: Avoid blind moves, reducing regret by 50% through informed decisions, leading to faster promotions or better well-being.

– **Embrace Audacity Like Lee**: Facing outnumbered odds, Lee’s bold invasion inspired his troops. In your life, take calculated risks—pitch that innovative idea at work or start a side hustle. Benefit: Builds confidence, potentially increasing income by 20-30% via new opportunities, while fostering a growth mindset that turns failures into stepping stones.

– **Cultivate Perseverance Like the Soldiers in the Cornfield**: Regiments that charged repeatedly, despite losses, held the line. Apply this by persisting through gym routines or learning a skill, even after initial failures. Benefit: Develops discipline, leading to long-term achievements like weight loss or skill mastery, enhancing self-esteem and life satisfaction.

– **Adapt Swiftly Like A.P. Hill’s Arrival**: Hill’s timely counterattack saved the day. In daily life, pivot quickly—adjust study methods if one fails or renegotiate deadlines at work. Benefit: Minimizes losses, turning potential disasters into wins, such as acing exams or securing project approvals, saving time and stress.

– **Seek Moral Clarity Like Lincoln’s Proclamation**: The battle’s aftermath reframed the war’s purpose. Define your core values—family, integrity—and align actions accordingly, like volunteering or ethical investing. Benefit: Provides purpose, reducing anxiety by focusing efforts, leading to deeper relationships and a legacy of positive impact.

### A Step-by-Step Plan to Integrate Antietam’s Wisdom

- **Assess Your Battlefield (Week 1)**: Identify a current challenge (e.g., career stagnation). Research it thoroughly—read books, consult mentors—like finding Special Order 191. Journal three key insights.

- **Plan Your Assault (Week 2)**: Outline a bold strategy with risks and contingencies, inspired by Lee’s invasion. Set measurable goals, such as applying to five jobs or exercising daily.

- **Execute with Grit (Weeks 3-6)**: Dive in, persisting through setbacks as in the Cornfield. Track progress weekly; adjust tactics mid-way, emulating Hill’s arrival.

- **Exploit the Breakthrough (Week 7)**: Once momentum builds (e.g., interview callback), push forward without hesitation, avoiding McClellan’s caution. Celebrate small wins to build morale.

- **Reflect and Reframe (Ongoing)**: Post-“battle,” evaluate outcomes and align with values, like Lincoln’s proclamation. Monthly reviews ensure growth, turning experiences into personal emancipation from limiting habits.