Imagine a narrow bridge spanning a lazy river, where two powerful men meet under the guise of peace, only for one to meet a bloody end at the hands of the other’s allies. This isn’t the plot of a thriller novel or a fantasy epic—it’s the real-life drama that unfolded on September 10, 1419, when John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, was assassinated during a parley with the future King Charles VII of France. This event, set against the chaotic backdrop of the Hundred Years’ War and a bitter civil strife, wasn’t just a personal vendetta; it reshaped the fate of nations, prolonged one of Europe’s longest conflicts, and highlighted the perilous dance of power, betrayal, and ambition. In this blog, we’ll dive deep into the historical intricacies of that fateful day, exploring the Duke’s life, the rivalries that led to his demise, and the far-reaching consequences. Along the way, we’ll uncover how this slice of medieval history can inspire us today to navigate our own conflicts with wisdom and foresight. Buckle up for a journey through time that’s as educational as it is enthralling—think Game of Thrones, but with real kings, dukes, and a whole lot of chainmail.

To set the stage, we must travel back to the 14th century, when Europe was a patchwork of kingdoms, duchies, and principalities, all jockeying for dominance. The Hundred Years’ War, which raged intermittently from 1337 to 1453 between England and France, wasn’t just about territorial squabbles; it was a complex web of dynastic claims, economic interests, and national identities in the making. At its core was the question of succession to the French throne. Edward III of England claimed the crown through his mother, Isabella of France, daughter of Philip IV. The French, adhering to Salic law which barred inheritance through females, crowned Philip VI of the House of Valois instead. What followed was a century of battles, sieges, and shifting alliances that drained treasuries, decimated populations, and left scars on the landscape.

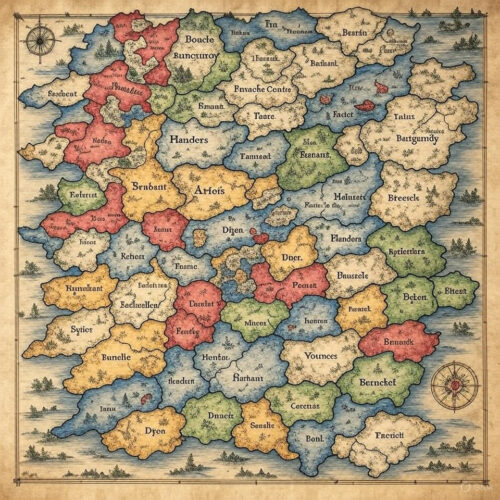

Enter the Duchy of Burgundy, a powerhouse in its own right. Burgundy wasn’t always the sprawling entity it became under the Valois dukes. Originally a kingdom in the early Middle Ages, it fragmented over time. In 1363, King John II of France granted the duchy to his son, Philip the Bold, as an appanage—a land grant to a younger royal son. Philip, through shrewd marriages and diplomacy, expanded Burgundy’s influence. He married Margaret III, Countess of Flanders, in 1369, bringing vast territories in the Low Countries under Burgundian control. These lands included Flanders, Brabant, Hainaut, and more, rich in trade, wool, and manufacturing. By the time Philip died in 1404, Burgundy was a semi-independent state straddling France and the Holy Roman Empire, with its dukes wielding power rivaling kings.

John the Fearless was born on May 28, 1371, in Dijon, the heart of Burgundy. As the eldest son of Philip the Bold and Margaret of Flanders, he was groomed for leadership from a young age. His early years were marked by the opulent court life of Burgundy, famous for its patronage of the arts, elaborate feasts, and chivalric ideals. But John wasn’t content with mere luxury; he craved action. In 1396, at age 25, he joined the Crusade of Nicopolis against the Ottoman Turks, a multinational effort led by Sigismund of Hungary. The crusade aimed to halt Ottoman expansion into Europe after their victory at Kosovo in 1389. John led a contingent of Burgundian knights, charging bravely into battle despite warnings of Ottoman superiority in numbers and tactics.

The Battle of Nicopolis on September 25, 1396, was a catastrophe for the crusaders. The allied forces, numbering around 16,000, faced an Ottoman army of up to 20,000 under Sultan Bayezid I. The crusaders’ heavy cavalry charged prematurely, getting bogged down in stakes and pitfalls. John fought valiantly, earning his moniker “the Fearless” for his refusal to retreat, but he was captured along with many nobles. Held in Bursa, he endured harsh conditions until a ransom of 200,000 gold ducats was paid in 1398, funded by his father’s duchy and loans from Italian bankers. This experience hardened John, teaching him the costs of impetuousness and the value of alliances—lessons that would define his political career.

Upon returning to Europe, John assisted his father in governing Burgundy. In 1384, he had inherited the County of Nevers from his maternal grandfather, Louis II of Flanders, adding to his holdings. In 1385, he married Margaret of Bavaria, daughter of Albert I, Duke of Bavaria-Straubing and Count of Holland, Zeeland, and Hainaut. This union not only brought potential inheritances but also strengthened Burgundy’s ties to the Low Countries. The couple had eight children, including Philip (the future Philip the Good) and several daughters who would marry into prominent families, weaving a web of dynastic connections.

When Philip the Bold died on April 27, 1404, John inherited the Duchy of Burgundy, the Counties of Burgundy (Franche-Comté), Artois, and Flanders. The following year, his mother Margaret died, adding Rethel, Antwerp, and Brabant to his portfolio. At 33, John was one of Europe’s most powerful princes, controlling territories that produced immense wealth from trade, agriculture, and taxation. But his ambitions extended beyond Burgundy; he eyed influence in France, where King Charles VI’s mental illness created a power vacuum.

Charles VI, known as “the Mad,” ascended the throne in 1380 at age 11. His uncles, including Philip the Bold, governed as regents until 1388, when Charles asserted control. However, in 1392, Charles suffered his first psychotic episode, attacking his own knights during a military expedition. Thereafter, his madness waxed and waned, leaving France governed by a council of princes. The main contenders for power were Louis I, Duke of Orléans (Charles’s brother), and John of Burgundy (after his father’s death).

The rivalry between John and Louis was intense. Louis, charming and extravagant, controlled the royal treasury, lavishing funds on his court and mistresses. He influenced the queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, and was rumored to have an affair with her. John, more austere and calculating, represented the interests of the Burgundian nobility and sought to curb Louis’s excesses. Tensions boiled over in 1405 when John accused Louis of embezzlement and sorcery. Public opinion in Paris, burdened by taxes, favored John, who positioned himself as a reformer.

Despite attempts at reconciliation, including a public embrace orchestrated by their uncle John, Duke of Berry, in November 1407, John decided to eliminate his rival. On November 23, 1407, as Louis left the queen’s residence in Paris, he was ambushed by masked assassins hired by John. They hacked Louis to death with axes and swords in the street, a brutal act that shocked France. John initially fled but returned to Paris, boldly admitting the deed in the Parlement. He justified it as “tyrannicide,” claiming Louis was a tyrant who practiced black magic and plotted against the king. Theologians at the University of Paris, swayed by Burgundian gold, endorsed this view in a treatise by Jean Petit.

The assassination ignited the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War, a conflict that overlapped with the Hundred Years’ War. Louis’s son, Charles of Orléans, aged 13, allied with his father-in-law, Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac, forming the Armagnac faction. They sought vengeance and control of the government. John, with his Burgundian supporters, held Paris initially. In 1408, the Armagnacs besieged Paris, but John repelled them. Peace was sworn in Chartres in 1409, absolving John and restoring his position. However, hostilities resumed. In 1410, both sides formed leagues, and skirmishes erupted across France.

John consolidated power by executing opponents, like Jean de Montagu, Grand Master of the King’s Household, in 1409. Montagu, an Armagnac sympathizer, was beheaded after a show trial. John also married his children strategically: his daughter Margaret to the Dauphin Louis in 1409 (though Louis died young), and Philip to Michelle of Valois in 1409. These ties aimed to embed Burgundy in the royal family.

The civil war weakened France just as England renewed its invasion. In 1413, Henry V ascended the English throne, ambitious to reclaim French lands. The Armagnacs, controlling the government, rebuffed Henry’s demands. John, exiled from Paris in 1413 after a popular uprising (the Cabochiens revolt, named after a butcher leader supported by Burgundians), negotiated secretly with Henry. Yet, when Henry invaded in 1415, John remained neutral, his troops arriving too late for the Battle of Agincourt on October 25, 1415. There, the French army was slaughtered; among the dead were John’s brothers, Anthony, Duke of Brabant, and Philip, Count of Nevers. John’s neutrality was seen as treacherous, but it preserved Burgundian strength.

By 1418, the tide turned. The Armagnacs’ harsh rule alienated Parisians. On May 29, 1418, Burgundian agents opened the gates to John’s forces. A massacre ensued, with thousands of Armagnacs killed. Bernard of Armagnac was lynched. John captured King Charles VI and Queen Isabeau, installing himself as regent. The Dauphin Charles (future Charles VII), then 15, escaped to Bourges, setting up a rival court. Northern France fell to the English, who captured Rouen in 1419.

Desperate for unity against the English, the Dauphin proposed peace talks. On July 10, 1419, John and the Dauphin met at Pouilly-le-Fort, swearing oaths of reconciliation on the Eucharist and signing a treaty. But trust was fragile. Armagnac hardliners, remembering Louis’s murder, pressed for revenge. John, wary but hopeful for a united front, agreed to another meeting on September 10, 1419, at Montereau-Fault-Yonne, southeast of Paris.

The site was a bridge over the Yonne River, chosen for neutrality. Barriers were erected at both ends, with each side allowed ten armed men. John arrived with his escort, including his chancellor and advisors. He knelt before the Dauphin, kissing his hand in homage. As discussions began on the bridge’s enclosed platform, tensions rose. According to Burgundian accounts, Tanneguy du Chastel, the Dauphin’s provost and a staunch Armagnac, shouted, “It’s time!” Armagnac men drew weapons, striking John. An axe blow cleaved his skull; others stabbed him repeatedly. John’s guards were overwhelmed, some killed, others captured.

Was the Dauphin complicit? Contemporary sources differ. Armagnac chronicles claim John drew a weapon first, justifying self-defense. Burgundian propaganda accused the Dauphin of premeditated murder, violating sacred oaths. Modern historians debate: some see evidence of Dauphin’s involvement, as he stood by during the attack; others argue he was manipulated by advisors like du Chastel. Regardless, the assassination was a masterstroke of vengeance for Louis’s death 12 years earlier.

The immediate aftermath was chaos. John’s body was mutilated—his right hand, which swore the oath, was severed. It was taken to Burgundy for burial in Dijon, where a grand tomb was later built by Claus Sluter, featuring mourning figures. News spread rapidly, horrifying Europe. In Paris, riots erupted against the Armagnacs.

John’s son, Philip the Good, aged 23, inherited Burgundy. Devastated and furious, Philip abandoned any French loyalty. On December 25, 1419, he allied with Henry V of England via the Treaty of Arras (later formalized in Troyes in 1420). This treaty disinherited the Dauphin, marrying Henry to Catherine of Valois and making him regent of France. Burgundy gained territories and autonomy. The alliance allowed English forces, bolstered by Burgundian troops, to conquer more of France. By 1422, Henry V and Charles VI were dead, leaving infant Henry VI as king of England and France, with Philip as a key supporter.

The civil war intensified, with France divided into three: English-occupied north, Burgundian east, and Armagnac (now Valois) south. Joan of Arc’s emergence in 1429 shifted momentum, leading to her capture by Burgundians in 1430 and execution in 1431. But Philip’s disillusionment grew; in 1435, the Treaty of Arras reconciled Burgundy with Charles VII, abandoning the English. This pivot helped France expel the English by 1453, ending the Hundred Years’ War.

The assassination’s legacy was profound. It prolonged the war by 15-20 years, causing untold suffering—famines, plagues, banditry. Burgundy’s “Golden Age” under Philip the Good flourished, with arts, literature, and courtly splendor, but at France’s expense. It underscored the fragility of feudal oaths and the dangers of factionalism in a monarchy weakened by madness.

Beyond politics, the event influenced culture. Chronicles like Enguerrand de Monstrelet’s detailed the murder, inspiring later works. The Burgundian court became a center for historiography, with Georges Chastellain glorifying John’s memory. In art, the tomb in Dijon symbolized mourning and power. The story echoed in Shakespearean tragedies, where betrayal on bridges or in parleys (think Julius Caesar) mirrored medieval realities.

Zooming out, the Hundred Years’ War, exacerbated by this murder, accelerated the transition from medieval to modern Europe. Feudal levies gave way to professional armies; gunpowder changed warfare; national identities solidified. France emerged centralized under the Valois, while Burgundy, after Charles the Bold’s death in 1477, was absorbed by the Habsburgs, setting the stage for future conflicts like the Italian Wars.

John the Fearless himself remains a controversial figure. Brave in battle, ruthless in politics, he embodied the chivalric ideal twisted by ambition. His policies expanded Burgundy to its zenith, but his methods sowed division. Historians like Richard Vaughan in his multi-volume study praise his administrative reforms—standardizing taxes, fostering trade—while condemning his violence.

The civil war’s atrocities were grim: massacres in Paris, sieges starving civilians, mercenaries (é corcheurs) ravaging countrysides. In 1418 alone, over 10,000 died in Paris purges. The war’s cost: France’s population dropped from 17 million in 1300 to 10 million by 1450, due to war, Black Death, and famine.

Shifting gears from the annals of history to the present day, what can we glean from this tale of treachery on a medieval bridge? The assassination of John the Fearless teaches us about the perils of unresolved grudges and the power of genuine reconciliation. In a world still rife with divisions—be it in politics, workplaces, or personal relationships—learning to bridge gaps (pun intended) can prevent small conflicts from escalating into life-altering disasters. By applying these lessons, you can foster stronger connections, reduce stress, and achieve personal growth. Here’s how this historical fact benefits you today:

– **Cultivate Trust Through Open Communication:** Just as false reconciliations led to John’s doom, superficial apologies in your life can breed resentment. Benefit by initiating honest conversations in strained relationships, leading to deeper bonds and reduced anxiety.

– **Avoid Escalation of Minor Disputes:** The rivalry started with political jostling but ended in murder; similarly, workplace rivalries or family feuds can spiral. Gain by addressing issues early, saving time, energy, and potentially career opportunities.

– **Embrace Neutral Ground for Resolutions:** The bridge was meant to be neutral but wasn’t; choose impartial settings for tough talks, like a coffee shop for family disputes, to promote fairness and better outcomes.

– **Learn from Past Mistakes Without Vengeance:** The Armagnacs’ revenge prolonged war; in your life, forgive past wrongs to break cycles of negativity, improving mental health and opening doors to new collaborations.

– **Build Alliances Strategically:** John’s son turned to England out of anger; you can form positive networks in your community or profession, leading to support systems that enhance success and happiness.

To put this into action, here’s a practical, step-by-step plan to apply the lessons from September 10, 1419, to your individual life:

- **Reflect on Your Conflicts:** Spend 15 minutes journaling about a current or past grudge. Identify the root cause, much like the power struggle between John and Louis.

- **Seek Historical Perspective:** Read a short article or book excerpt on a similar historical event (like this one!) to gain objectivity—remind yourself how unchecked ambition leads to ruin.

- **Initiate a Neutral Dialogue:** Contact the person involved and suggest a meeting in a neutral, low-pressure environment. Prepare by listing mutual benefits of resolution.

- **Practice Active Listening:** During the talk, focus on understanding their side without interrupting, echoing the failed parleys of 1419 to avoid repeats.

- **Seal with Actionable Commitments:** End with specific promises, like weekly check-ins, and follow through—unlike the broken oaths on the bridge.

- **Review and Adjust:** After a month, assess the outcome. If successful, apply to another conflict; if not, seek mediation from a trusted third party.

- **Celebrate Progress:** Reward yourself for bridging divides, perhaps with a treat, reinforcing positive behavior for long-term personal empowerment.

By channeling the cautionary tale of John the Fearless, you’re not just learning history—you’re arming yourself with tools for a more harmonious, resilient life. Who knew a 600-year-old murder could be your secret to modern success? History isn’t dead; it’s your motivational coach in disguise.