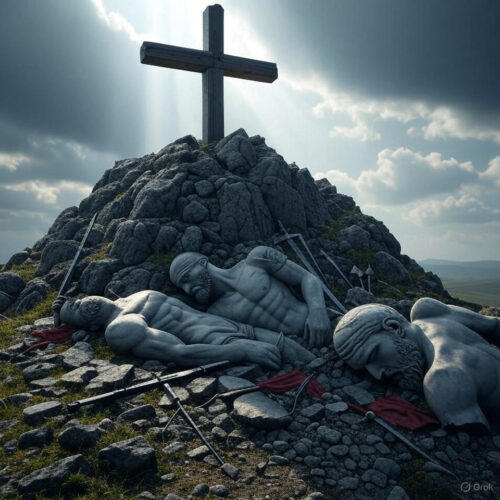

Imagine a raging river cutting through the jagged peaks of the Julian Alps, where the fate of an empire hung in the balance amid howling winds and clashing swords. On September 6, 394 AD, the Battle of the Frigidus unfolded as a dramatic showdown between two Roman emperors, pitting the forces of tradition against the tide of transformation. This wasn’t just a skirmish over territory; it was a pivotal moment that sealed the dominance of Christianity in the Roman Empire and marked the end of large-scale pagan resistance. As we dive into this enthralling chapter of distant history, we’ll uncover the intricate web of politics, religion, and military genius that defined the era. And while the bulk of our journey will immerse you in the rich tapestry of historical facts, we’ll cap it off with motivational insights on how this ancient triumph can supercharge your personal growth today. Get ready for a rollercoaster of education and inspiration—history has never been this exhilarating!

The Roman Empire in the late 4th century was a colossal entity stretched thin by internal divisions, barbarian pressures, and religious upheavals. By 394 AD, the empire had been split into Eastern and Western halves since the death of Emperor Theodosius I’s predecessor, but tensions simmered like a volcano ready to erupt. Theodosius, ruling from Constantinople in the East, was a staunch Nicene Christian who had already made waves by issuing edicts that suppressed pagan practices and Arian Christianity, a variant deemed heretical by the orthodox church. His policies, including the closure of pagan temples and the prohibition of sacrifices, were part of a broader campaign to unify the empire under one faith.

The spark that ignited the Battle of the Frigidus was the mysterious death of Western Emperor Valentinian II on May 15, 392 AD. Valentinian, a young ruler under the thumb of his powerful Frankish general Arbogast, was found hanged in his palace in Vienne, Gaul. Official reports claimed suicide, but whispers of foul play spread like wildfire. Arbogast, a pagan of Frankish origin who had risen through the ranks to become magister militum (master of soldiers), was suspected of orchestrating the death to install a more pliable puppet. Valentinian’s sister Galla, married to Theodosius, fueled suspicions by insisting her brother had been murdered. Theodosius, already wary of Arbogast’s influence, refused to recognize the general’s choice for successor.

Arbogast, undeterred, proclaimed Eugenius emperor on August 22, 392 AD. Eugenius was no warrior; he was a scholarly rhetorician and former magister scrinii (secretary), respected in Roman circles for his eloquence and administrative skills. Yet, he was a nominal Christian with strong sympathies toward paganism, which appealed to the empire’s remaining pagan elite, including senators in Rome and the praetorian prefect Nicomachus Flavianus. Flavianus, a fervent pagan, revived ancient rituals and restored temples, signaling a potential renaissance of the old gods. This move directly challenged Theodosius’s Christian agenda, turning the conflict into a proxy war between Christianity and paganism.

For over a year, diplomatic maneuvers failed. Theodosius elevated his young son Honorius to augustus in January 393, effectively declaring war on the usurpers. Preparations for invasion began in earnest. The Eastern army, battered from previous defeats like the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD where Emperor Valens perished along with much of the elite forces, needed rebuilding. Generals like Flavius Stilicho, a half-Vandal rising star, and Timasius drilled the troops relentlessly. Theodosius also consulted oracles—ironically blending Christian piety with ancient traditions. According to historians like Claudian and Sozomen, a Christian monk in Egypt prophesied a bloody but victorious outcome for Theodosius.

By May 394, Theodosius marched from Constantinople with a formidable force. His army included 20,000 to 30,000 Roman legionaries, bolstered by 20,000 Visigothic federates under their ambitious chieftain Alaric, who would later sack Rome in 410 AD. Additional contingents came from Syrian archers and Caucasian Iberians led by Bacurius the Iberian, a prince known for his bravery. The total strength hovered around 40,000 to 50,000 men, a mix of disciplined infantry, cavalry, and auxiliary barbarians eager for plunder.

On the Western side, Arbogast and Eugenius commanded a comparable force of 35,000 to 50,000 soldiers, drawn from Franks, Alemanni, Gallo-Romans, and Gothic auxiliaries. Arbogast, drawing from his victory over the usurper Magnus Maximus in 388 AD, opted for a defensive strategy. He concentrated his troops in northern Italy, leaving the Alpine passes open to lure Theodosius into a trap. Eugenius set up camp near the Frigidus River (modern Vipava River in Slovenia), a strategic chokepoint in the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum, a series of fortifications guarding the gateway to Italy. The location was ideal: narrow valleys flanked by steep mountains, where superior numbers could be neutralized.

As Theodosius approached in late August, religious symbolism intensified. Eugenius, courting pagan support, erected a statue of Jupiter on a hill overlooking the battlefield and adorned banners with images of Hercules, invoking divine favor from the old gods. Theodosius, in contrast, rallied his troops with Christian banners and prayers, framing the battle as a holy war. Scouts reported the terrain: the Frigidus Valley was a cold, windy corridor prone to sudden storms, with the river swollen from mountain runoff.

The battle commenced on September 5, 394 AD. Theodosius, perhaps overconfident or lacking proper reconnaissance, launched his assault without fully assessing the defenses. He committed his Visigothic allies first, a tactical decision that some historians interpret as a cynical move to weaken potential future threats—the Goths had been restive since Adrianople. Alaric’s warriors charged headlong into Arbogast’s lines, facing a hail of arrows and javelins from entrenched positions. The fighting was brutal; waves of Gothic infantry smashed against Gallo-Roman shields, but the Western forces held firm.

By dusk, the Eastern advance had stalled. Casualties were staggering: around 10,000 Goths lay dead, including the valiant Bacurius, who fell leading a charge. Eugenius’s camp erupted in celebration, with soldiers hailing their emperor as invincible. Arbogast, ever the strategist, dispatched a detachment under night cover to circle behind Theodosius and block the mountain passes, aiming to trap the invaders.

That night, Theodosius’s camp was a scene of despair. Soldiers huddled against the chill, morale plummeting. Legend has it that Theodosius spent the hours in prayer, beseeching God for aid. Whether divine or coincidental, aid arrived at dawn on September 6. Reports trickled in: Arbogast’s flanking force had defected, swelling Theodosius’s ranks and opening escape routes. Buoyed, the Eastern army reformed for a second assault.

What followed was one of history’s most dramatic turnarounds. As the lines engaged, a ferocious tempest—the infamous bora wind—swept down from the east. This katabatic wind, common in the region, hurled gusts exceeding 100 km/h, blinding Western troops with dust and debris. Arrows fired by Arbogast’s archers reportedly boomeranged back into their own ranks. Christian chroniclers like Orosius and Augustine amplified this as a miracle, akin to biblical interventions. Pagan sources, such as Zosimus, downplayed it, attributing victory to betrayal.

Regardless, the wind disrupted Western formations. Theodosius’s cavalry, led by Stilicho, exploited the chaos, flanking and shattering the lines. Hand-to-hand combat ensued: legionaries in scale armor clashed with Frankish warriors wielding franciscas (throwing axes), while Gothic berserkers hacked through with longswords. By afternoon, resistance crumbled. Eugenius was captured fleeing his tent; despite begging for mercy, he was beheaded on the spot. Arbogast escaped into the hills but, realizing pursuit was relentless, fell on his sword days later.

The immediate aftermath was grim. Casualties totaled perhaps 20,000 on each side, depleting the empire’s military strength at a time when barbarian incursions loomed. Theodosius entered Milan triumphantly, pardoning many but executing key pagan supporters like Flavianus, who committed suicide. He reunited the empire briefly, installing Honorius as Western emperor under Stilicho’s regency. Arcadius ruled the East.

The battle’s significance reverberates through history. It marked the definitive triumph of Christianity over organized paganism in the Roman world. Theodosius, already having issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD declaring Nicene Christianity the state religion, now enforced it empire-wide. Pagan temples were demolished, sacrifices banned, and the Olympic Games ended in 393 AD. This paved the way for the medieval Christian order, influencing everything from Byzantine art to the Holy Roman Empire.

Historians debate the religious framing: was it truly Christianity versus paganism? Eugenius was Christian, albeit tolerant of pagans, and Arbogast pagan, but the conflict was as much about power as faith. Nonetheless, the outcome accelerated Christianization, weakening senatorial paganism and bolstering the church’s authority. It also highlighted the empire’s fragility; Theodosius died on January 17, 395 AD, from edema, leaving a divided realm to his inept sons. The heavy losses, especially among Goths, sowed seeds for Alaric’s later revolt.

Environmentally, the bora wind underscores how natural forces can sway human events, a theme echoed in battles like Agincourt or Normandy. Strategically, Arbogast’s defense showcased Roman engineering, while Theodosius’s adaptability turned defeat into victory. Culturally, the battle inspired literature: Claudian’s panegyrics glorified Theodosius, while modern scholars like Alan Cameron analyze its propaganda.

Diving deeper into the key figures: Theodosius I, born in 347 AD in Hispania, rose from military ranks, suppressing rebellions in Britain and Africa. His faith was profound; he underwent baptism only after a near-fatal illness in 380 AD, reflecting delayed conversion common then. Stilicho, his son-in-law, became a legendary general, defending against Vandals and Goths until his execution in 408 AD. Alaric, the Visigoth king, used Frigidus as a stepping stone, demanding lands and gold post-battle.

Eugenius, a teacher of grammar and rhetoric, represented the educated elite clinging to classical traditions. His coinage featured pagan motifs, like Victoria holding a wreath, subtly challenging Theodosius. Arbogast, son of a Frankish noble, embodied barbarian integration into Roman command, his suicide a stoic end befitting Roman ideals.

The location itself adds intrigue. The Vipava Valley, near modern Ajdovščina, Slovenia, features karst landscapes with caves and sinkholes, ideal for ambushes. Archaeological finds, including Roman fortifications, confirm the site’s importance as a barrier against eastern invaders.

Expanding on troop compositions: Eastern forces included limitanei (border troops) and comitatenses (field armies), with Gothic foederati providing shock infantry. Western armies relied on Germanic mercenaries, their loyalty fickle—as seen in the defection. Weapons ranged from spatha swords to plumbatae darts, with cataphract cavalry on both sides.

Chroniclers vary: Christian writers like Rufinus portrayed it as divine judgment, while pagan Eunapius lamented the old gods’ fall. The battle’s cost weakened Rome against the 5th-century invasions, contributing to the Western Empire’s collapse in 476 AD.

Now, shifting gears to motivation—while history dominates our tale, the Battle of the Frigidus offers timeless lessons. In a world of uncertainty, like the winds that turned the tide, unexpected allies or opportunities can flip your fortunes. Theodosius’s perseverance amid near-defeat teaches resilience, while his faith inspires belief in higher purposes.

Here’s how you can benefit today by applying these historical facts to your individual life:

– **Embrace Adaptability in Challenges**: Just as the bora wind shifted the battle, learn to pivot when obstacles arise. In your career, if a project stalls, reassess and use external factors—like market changes—to your advantage, turning potential loss into gain.

– **Cultivate Strategic Alliances**: Theodosius integrated diverse forces, including Goths. Build a network of varied mentors and colleagues; for instance, join cross-industry groups to gain fresh perspectives that strengthen your professional edge.

– **Harness Inner Conviction**: Theodosius’s prayers symbolized unshakeable belief. Start a daily affirmation routine to boost confidence; if facing a job interview, visualize success to channel that emperor-like resolve.

– **Learn from Setbacks**: The first day’s rout didn’t doom Theodosius. After a personal failure, like a failed business venture, analyze it objectively and launch a comeback plan, mirroring the second-day assault.

– **Promote Unity in Diversity**: The battle unified the empire under one faith. In family or team settings, foster inclusivity by organizing group activities that celebrate differences, enhancing harmony and productivity.

To implement these, follow this step-by-step plan:

- **Reflect on History**: Spend 15 minutes daily reading about Frigidus-like events to internalize resilience—use apps like History Hit for bite-sized lessons.

- **Assess Your Battles**: Identify a current challenge (e.g., weight loss) and map it like a battlefield: list obstacles, allies, and potential “winds” (opportunities).

- **Build Faith and Strategy**: Dedicate mornings to meditation or journaling on convictions, then outline adaptive tactics, such as alternative career paths.

- **Act with Perseverance**: Commit to small daily actions, like networking calls, tracking progress weekly to celebrate wins.

- **Review and Adapt**: Monthly, evaluate outcomes and adjust, ensuring your “empire” thrives.

This ancient saga isn’t dusty relics—it’s fuel for your epic life. Rise like Theodosius, and conquer your world!