Welcome to a journey through time, where the echoes of ancient battles still whisper lessons for our modern lives. On August 13, 1521, the vibrant heart of the Aztec Empire, the majestic city of Tenochtitlan, fell to Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés. This wasn’t just the end of a siege; it was the collapse of an empire that had dominated Mesoamerica for centuries. In this blog, we’ll dive deep into the intricate details of this monumental event—exploring the background, the brutal siege, the key players, and the dramatic finale—with a treasure trove of historical facts to make it as educational as it is engaging. Then, we’ll bridge the centuries to show how the resilience displayed in this saga can supercharge your daily life today. Get ready for a fun, fact-packed ride that’s equal parts history lesson and motivational boost!

The Aztec Empire, or the Triple Alliance as it was formally known, was a powerhouse in pre-Columbian America. Formed in 1428 after the Tepanec War, it united the cities of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan under a system of tribute and conquest. Tenochtitlan, built on an island in Lake Texcoco, was a marvel of engineering. Founded in 1325 according to legend—when the Mexica people saw an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a snake, fulfilling a prophecy—the city grew to house over 200,000 residents by the early 16th century, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time, rivaling Paris or Constantinople. Its layout featured wide canals for transportation, chinampas (floating gardens) for agriculture, and massive temples like the Templo Mayor, dedicated to Huitzilopochtli (god of war) and Tlaloc (god of rain). The empire spanned about 135,000 square kilometers, controlling a population of around 11 million through a network of client states that paid tribute in goods like jade, cotton, cacao, and feathers.

The Aztecs’ society was highly stratified, with the tlatoani (emperor) at the top, followed by nobles, priests, warriors, merchants, farmers, and slaves. Human sacrifice played a central role in their religion, believed to sustain the gods and prevent the end of the world. This practice, along with heavy tribute demands, bred resentment among subjugated peoples like the Tlaxcalans, who remained independent and became crucial allies to the Spaniards. The empire’s military was formidable, with elite warrior orders like the Jaguar and Eagle knights, armed with macuahuitl (obsidian-edged clubs), atlatls (spear-throwers), and cotton armor.

Enter the Spaniards. In 1492, Christopher Columbus’s voyage opened the door to European exploration of the Americas, but it was the tales of rich lands from expeditions like Juan de Grijalva’s in 1518 that ignited greed. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, governor of Cuba, commissioned Hernán Cortés, a cunning lawyer-turned-adventurer from Medellín, Spain, to lead an expedition. Cortés, born in 1485, had arrived in the New World in 1504 and participated in the conquest of Cuba. Defying Velázquez’s orders to limit the mission to trade, Cortés set sail from Cuba on February 18, 1519, with 11 ships, 508 soldiers, 100 sailors, 16 horses, 11 cannons, and dogs. He landed at Potonchán, where he defeated the locals and received 20 women, including Malintzin (La Malinche), who became his interpreter and advisor, eventually bearing his son Martín.

Cortés founded Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz on April 22, 1519, establishing a town council to legitimize his independence from Velázquez. He then sank his ships to prevent desertion, a bold move that committed his men to conquest. Marching inland, he allied with the Totonacs of Cempoala, who resented Aztec tribute collectors. In September 1519, Cortés battled the Tlaxcalans in a series of fierce encounters. The Tlaxcalans, led by Xicotencatl the Elder and his son Xicotencatl the Younger, initially resisted with thousands of warriors, but after defeats—thanks to Spanish steel swords, crossbows, arquebuses, and cavalry charges—they allied with Cortés, providing 6,000 warriors and crucial intelligence. This alliance was pivotal; without it, the conquest might have failed.

On November 8, 1519, Cortés entered Tenochtitlan via the southern causeway, greeted by Moctezuma II (Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin), the ninth tlatoani, who ruled from 1502. Moctezuma, believing Cortés might be the god Quetzalcoatl returning as prophesied, housed the Spaniards in the palace of Axayacatl. But tensions rose. On November 14, Cortés took Moctezuma hostage after accusations of Aztec attacks on Veracruz. For months, Moctezuma ruled as a puppet, even pledging allegiance to King Charles V of Spain. The Spaniards melted down Aztec gold into bars, amassing wealth.

Trouble brewed when Velázquez sent Pánfilo de Narváez with 900 men to arrest Cortés in April 1520. Cortés left Pedro de Alvarado in charge of Tenochtitlan with 120 men and marched to the coast, defeating Narváez at Cempoala on May 27, 1520, and recruiting his forces. Meanwhile, in Tenochtitlan, Alvarado, fearing a plot, massacred thousands of Aztec nobles during the Toxcatl festival on May 20, 1520, sparking a revolt. Cortés returned on June 24, but the city was in uproar. Moctezuma, addressing the crowd from a rooftop on June 29, was stoned and died three days later (accounts vary on whether from stones or Spanish hands).

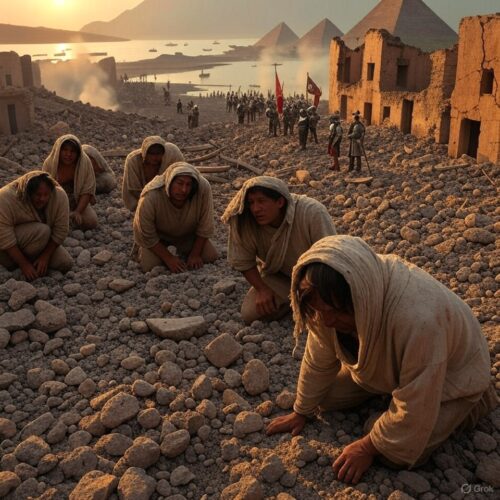

The Spaniards fled during La Noche Triste on June 30-July 1, 1520. Crossing the causeways under cover of night, they were attacked by Aztec warriors in canoes. Using a portable bridge, they attempted to cross gaps, but chaos ensued. Over 600 Spaniards and 2,000 Tlaxcalans died, along with most horses and cannons. Cortés wept under a tree (the “Tree of the Sad Night”) but regrouped at Tlaxcala.

Cuitláhuac, Moctezuma’s brother, became tlatoani but died of smallpox in December 1520, introduced by Narváez’s forces. The epidemic ravaged the Aztecs, killing up to 40% of Tenochtitlan’s population, including many leaders, while Spaniards were immune. Cuauhtémoc, Moctezuma’s nephew, became the last tlatoani in February 1521.

Cortés prepared for revenge. In Tlaxcala, he built 13 brigantines (small ships) under shipwright Martín López, using parts from scuttled ships and local timber. These were disassembled, transported over mountains, and reassembled on Lake Texcoco. He amassed an army of 700 Spaniards, 118 crossbowmen and gunners, 86 horses, 3 heavy cannons, 15 field guns, and over 200,000 indigenous allies from Tlaxcala, Texcoco, Huexotzingo, Chalco, and others resentful of Aztec rule.

The siege began on May 26, 1521. Cortés divided his forces into three divisions:

– Pedro de Alvarado with 30 cavalry, 18 crossbowmen/gunners, 150 infantry, and 25,000 Tlaxcalans at Tacuba (west causeway).

– Cristóbal de Olid (later replaced by Gonzalo de Sandoval) with 24 cavalry, 13 gunners, 150 infantry, and 30,000 allies at Coyoacan (south).

– Gonzalo de Sandoval with 24 cavalry, 4 gunners, 150 infantry, and 20,000 allies at Iztapalapa (east).

Cortés commanded the brigantines. The strategy was to control the lake, destroy Aztec canoes, cut off supplies, and advance along causeways, filling gaps with rubble from demolished buildings.

Key tactics:

– Spaniards used brigantines armed with cannons to dominate the lake, ramming and sinking hundreds of Aztec canoes in early battles.

– On land, infantry advanced in formation, protected by shields, with cavalry charges breaking Aztec lines. Crossbows and guns provided ranged fire, though powder was limited.

– Aztecs countered with guerrilla tactics: ambushes from rooftops, pits with stakes, and canoe attacks. They removed causeway sections at night, forcing Spaniards to fill them daily.

– The Chapultepec aqueduct was cut on May 26, forcing Aztecs to rely on brackish lake water and rain, leading to thirst and disease.

Early events:

– May 28: Brigantines launched, defeating 500 Aztec canoes.

– June 1: Alvarado and Olid linked up, encircling the city.

– June 16: Cortés captured a hill near Tacuba, but Aztecs counterattacked.

– June 23: A coordinated assault failed when Aztecs captured 60 Spaniards, sacrificing them on temples in view of their comrades, demoralizing the invaders.

By July, famine gripped the city. Aztecs ate lizards, swallows, corn husks, and grass. Dysentery and smallpox weakened them. Cortés offered peace, but Cuauhtémoc refused.

Final push:

– July 25: Sandoval captured the eastern sector.

– August 1: Alvarado advanced into Tlatelolco, the northern district where survivors fled.

– August 7: A massive assault saw Spaniards reach the marketplace, burning temples.

– August 13: Cuauhtémoc attempted to flee in a canoe but was captured by García Holguín on a brigantine. He surrendered, touching Cortés’ dagger and saying, “I have done all that I could to defend my people.” The city fell after 93 days.

Casualties were staggering. Aztec losses: 100,000-240,000 dead from combat, starvation, and disease (city population reduced from 200,000 to 30,000). Spanish losses: About 100 Spaniards killed during the siege, plus thousands of allies. The city was razed; temples destroyed, houses burned, canals filled with corpses.

Outcomes: The fall marked the end of the Aztec Empire, paving the way for Spanish colonial rule in New Spain. Cortés became governor, founding Mexico City on the ruins. Treasure was divided, though much was lost. Indigenous allies were rewarded with land and exemptions, but many later rebelled against Spanish exploitation. Culturally, it led to syncretism, like the Virgin of Guadalupe blending with Aztec goddesses.

Historical significance: This event accelerated European colonization, spreading Christianity, languages, and diseases across the Americas. It highlighted the role of alliances and technology in conquests, and the fragility of empires built on oppression. Economically, silver from Mexico funded European wars. It also sparked debates on colonialism’s ethics, with figures like Bartolomé de las Casas condemning atrocities.

Now, let’s turn this epic tale into fuel for your life. The siege of Tenochtitlan teaches us about resilience—the Aztecs’ unyielding defense and Cortés’ relentless strategy show that perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds can change destinies. Here’s how you can apply this historical grit to your individual life today, with specific bullet points and a step-by-step plan to build unbreakable determination.

– **Embrace Alliances Like Cortés Did with the Tlaxcalans**: In your career, seek mentors or collaborators who complement your weaknesses. For example, if you’re launching a business, partner with someone skilled in marketing if you’re strong in product development—this can turn potential rivals into assets, just as Tlaxcalan warriors bolstered Spanish forces.

– **Adapt Tactics Mid-Battle, as the Spaniards Filled Canals with Rubble**: When facing personal setbacks like job loss, pivot quickly. Update your resume with new skills learned online, network on LinkedIn daily, and apply to 5 jobs a week, transforming obstacles into stepping stones.

– **Endure Hardships Like the Aztecs During Famine**: In fitness goals, when motivation wanes, recall their survival on minimal resources. Commit to a 30-day challenge: walk 10,000 steps daily, eat whole foods, and track progress in a journal to build physical and mental toughness.

– **Plan Long-Term Like Cortés Building Brigantines**: For financial independence, create a budget allocating 20% of income to savings, invest in low-cost index funds, and review quarterly—mirroring the months-long preparation that won the lake battles.

– **Learn from Defeat, Avoiding La Noche Triste Mistakes**: After a failed relationship, reflect on communication breakdowns, seek therapy sessions weekly, and set boundaries in future interactions to prevent repeated errors.

The Perseverance Plan: A 4-Week Blueprint Inspired by Tenochtitlan

- **Week 1: Assess Your Battlefield** – Identify your ’empire’ (goals) and ‘enemies’ (obstacles). Journal daily about strengths (your ‘allies’) and weaknesses (gaps to fill), aiming for 3 entries per day.

- **Week 2: Build Your Brigantines** – Prepare tools. Enroll in an online course for skill-building, create a vision board with 10 images representing success, and schedule daily 15-minute planning sessions.

- **Week 3: Launch the Siege** – Take action. Break a big goal into daily tasks (e.g., if writing a book, write 500 words daily), track wins in a app, and adjust tactics if progress stalls.

- **Week 4: Claim Victory and Reflect** – Celebrate milestones with a reward (like a favorite meal), review what worked, and plan the next ‘conquest’ to maintain momentum.

This historical saga isn’t just past—it’s a playbook for triumph. Channel the spirit of Tenochtitlan, and watch your life transform!