Imagine a sun-baked Mediterranean island, where towering cliffs meet the azure sea, and a fortified town clings to the heights like a eagle’s nest. On August 1, 902 AD, the air was thick with the clamor of battle cries, the clash of steel, and the acrid smoke of siege engines. This was Taormina, the last bastion of the Byzantine Empire in Sicily, falling to the relentless Aghlabid armies after a grueling two-year siege. This wasn’t just a military conquest; it was the culmination of a 75-year saga of ambition, betrayal, and cultural transformation that reshaped the island forever. Today, as we dust off this chapter from distant history, we’ll dive deep into the riveting details of this event—far more history than pep talk, I promise—while uncovering how its lessons can ignite your own path to resilience and success. Buckle up for a journey through time that’s equal parts educational thriller and motivational spark.

The story of Taormina’s fall begins long before that fateful August day, rooted in the turbulent geopolitics of the early medieval world. Sicily, under Byzantine rule since the 6th century, was a jewel in the empire’s crown. Conquered by Emperor Justinian I in the 530s during his ambitious reconquest of the Western Roman territories, the island served as a vital bridge between the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) heartland in Constantinople and its outposts in Italy and North Africa. It was rich in resources—fertile valleys producing wheat, olives, and wine—and strategically positioned to control maritime trade routes. Byzantine administration was hierarchical, with a strategos (military governor) overseeing defenses from Syracuse, the island’s capital. Fortifications dotted the landscape, from hilltop castles to walled cities, designed to repel invaders. Yet, by the 9th century, the empire was stretched thin, battling threats from Bulgars in the Balkans, Arabs in the Levant, and internal iconoclastic controversies.

Enter the Muslims of North Africa. The Aghlabid dynasty, ruling Ifriqiya (roughly modern Tunisia) as semi-independent emirs under the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, eyed Sicily with envy. Founded by Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab in 800 AD, the Aghlabids were a Sunni Arab family who had quelled Berber revolts and built a prosperous state through agriculture, trade, and piracy. Their society blended Arab, Berber, and African elements, with a strong emphasis on jihad (holy war) to legitimize rule and unite fractious tribes. Early raids on Sicily began in the 7th century—quick hits for loot and slaves—but these escalated in the 8th century. In 805, an Aghlabid fleet sacked the island’s coasts, and by 813, they had temporarily seized Mazara del Vallo in the west. These probes revealed Byzantine weaknesses: slow reinforcements from Constantinople and local discontent with heavy taxation and religious policies.

The full-scale invasion ignited in 827 AD, sparked by a classic tale of betrayal and ambition. Euphemius, a Byzantine naval commander (tourmarches) in Sicily, rebelled against Emperor Michael II. Sources vary on his motives—some say he forcibly married a nun named Homoniza, incurring imperial wrath; others suggest political aspirations. Euphemius seized Syracuse, proclaimed himself basileus (emperor), and minted coins in his image. But loyalist forces, led by generals like Plato of Palermo and Constantine (the island’s strategos), crushed his rebellion. Fleeing to Ifriqiya, Euphemius begged Aghlabid Emir Ziyadat Allah I for aid, promising tribute and recognition of Muslim suzerainty. Ziyadat Allah, facing domestic unrest from feuding Arab and Berber factions and pressure from religious scholars to wage jihad, seized the chance. He assembled a fleet of 100 ships and an army of 10,000 infantry and 700 cavalry, commanded by the respected qadi (judge) Asad ibn al-Furat, a 70-year-old scholar-warrior known for his legal treatises and military prowess.

Landing at Mazara del Vallo on June 17, 827, the invaders quickly defeated a Byzantine force under Balata (likely a title for a local commander). Euphemius, however, proved a liability; suspicious of his ambitions, Asad marginalized him, and Euphemius was later assassinated by his own guards in 828 during a failed plot. The Muslims besieged Syracuse but withdrew after a plague outbreak and the arrival of Byzantine reinforcements from Venice and Constantinople. They fortified Mineo as a base and pushed westward, capturing Agrigento in 828 after a brutal siege where starvation led to cannibalism among defenders. By 831, Palermo fell after a year-long blockade, its population reduced from 70,000 to mere thousands due to famine and disease. The city became the Muslim capital, renamed al-Madinah, and flourished under new irrigation systems and markets.

The conquest dragged on for decades, a grinding war of attrition. The Byzantines, under emperors like Theophilos (r. 829–842), sent expeditions but couldn’t commit fully due to threats elsewhere. Key battles included the fall of Enna (Castrogiovanni) in 859, a mountainous fortress that resisted for years until betrayed by a local commander. The Muslims employed innovative tactics: catapults hurling stones and fire, mining under walls, and psychological warfare through feigned retreats. Berber troops excelled in guerrilla raids, while Arab cavalry provided mobility. Internal divisions plagued both sides—Muslim forces suffered from ethnic rivalries, leading to mutinies, while Byzantines dealt with Lombard and Slavic mercenaries of dubious loyalty.

By the 870s, the noose tightened around eastern Sicily. Syracuse, the Byzantine nerve center, endured a nine-month siege in 877–878 led by Jafar ibn Muhammad. The city, defended by walls dating to ancient Greek times, held out heroically. Chroniclers describe desperate measures: citizens ate leather hides and ground bones for flour. A Byzantine relief fleet under Admiral Nasar arrived too late; on May 21, 878, the Muslims breached the walls, massacring 5,000 and enslaving the rest. The strategos was executed, and treasures looted, including relics sent to the Abbasid caliph. This catastrophe left Taormina isolated, the last major holdout in Val Demone (northeastern Sicily).

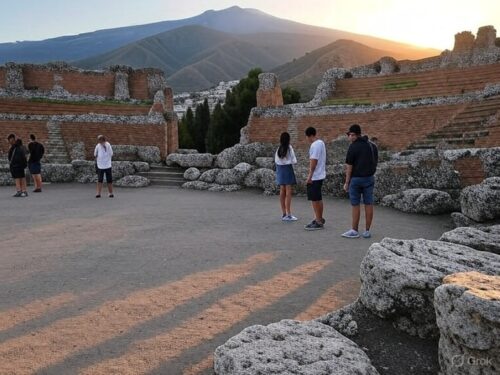

Taormina itself was a marvel of natural and man-made defenses. Perched on Mount Tauro at 200 meters above sea level, overlooking the Ionian Sea, it boasted ancient Greek roots as Tauromenion, founded in 396 BC. Under Byzantines, it was fortified with thick walls, towers, and a castle (likely the Saracen Castle ruins today). The town’s theater, famous today for its views of Mount Etna, served as a rally point. Its population included Greeks, Armenians, and Slavs, loyal to the Orthodox faith and emperor. As the conquest progressed, refugees from fallen cities swelled its numbers, making it a symbol of resistance.

The final push came under Aghlabid Emir Ibrahim II (r. 875–902), a complex figure: pious yet tyrannical, known for harsh justice and religious zeal. Facing rebellions in Ifriqiya, including a Shi’a uprising, Ibrahim revitalized the Sicilian campaign to burnish his jihad credentials. In 900, his son Abu’l-Abbas Abdallah raided Taormina’s outskirts, burning crops and capturing outposts. He besieged Catania but withdrew for winter. In 901, Abu’l-Abbas sacked Reggio in Calabria (mainland Italy), enslaving 15,000 and demonstrating cross-strait operations.

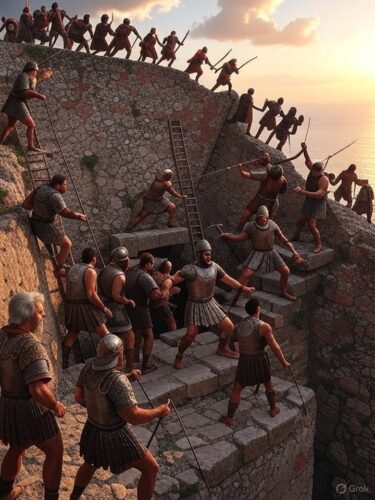

In early 902, a dramatic twist: Ibrahim II, pressured by his subjects and the Abbasid caliph al-Mu’tadid to abdicate due to his cruelty (he reportedly executed 300 officers for a defeat), swapped roles with his son. Abu’l-Abbas returned to Ifriqiya as heir, while Ibrahim, with a band of devoted volunteers, sailed to Sicily vowing eternal jihad. Landing in May, he swiftly defeated a Byzantine field army near Taormina, cutting supply lines. The siege intensified: Muslim engineers built mangonels (catapults) and battering rams, while archers rained arrows. Starvation set in as Ibrahim blocked sea access, despite Byzantine attempts to smuggle supplies.

Chroniclers paint a vivid picture: defenders, led by an unnamed strategos, hurled stones and boiling oil from the walls. Women and children aided in repairs, inspired by religious fervor. But no relief came from Constantinople—Emperor Leo VI was embroiled in wars with Bulgars and Arabs in Anatolia. After two years of intermittent blockade (some sources date the full siege from 901), cracks appeared. On August 1, 902, Ibrahim’s forces stormed the weakened gates. The assault was ferocious; resistance collapsed, and the town was sacked. Most inhabitants were killed or enslaved—Ibrahim reportedly spared only those who converted, though accounts vary. The emir sent the heads of prominent defenders to Palermo as trophies.

The fall’s immediate impact was profound. With Taormina gone, minor fortresses like Rometta and Aci submitted, completing the conquest. Sicily became the Emirate of Sicily, a Muslim province paying tribute to the Aghlabids until their fall to the Fatimids in 909. Ibrahim, triumphant, pushed into Italy, besieging Cosenza, but died of dysentery on October 23, 902, his body returned to Palermo for burial. His death marked the end of an era, but his legacy endured.

Under Muslim rule, Sicily transformed. Arabs introduced advanced agriculture: citrus fruits, sugarcane, and irrigation via qanats (underground channels), boosting productivity. Palermo grew into a cosmopolitan hub with 300 mosques, gardens, and libraries. Cultural fusion emerged—Greek, Latin, and Arabic coexisted, influencing cuisine (think couscous and marzipan), architecture (Norman-Arab-Byzantine styles), and science. Poets like Ibn Hamdis sang of the island’s beauty, while administrators like the Kalbids (post-948) fostered tolerance, allowing Christians and Jews to practice faiths under dhimmi status.

Fun historical nuggets abound. Did you know the conquest inspired legends? Euphemius’s betrayal echoes Judas-like tales in Byzantine chronicles. Taormina’s theater, site of gladiatorial games in Roman times, may have hosted victory celebrations post-fall. Mount Etna, erupting in 902, was seen as an omen—Muslims interpreted it as divine favor, Byzantines as wrath. The event rippled beyond Sicily: it weakened Byzantine Italy, paving the way for Lombard and Norman incursions, and boosted Arab naval power, threatening Rome itself.

The conquest wasn’t without setbacks for the victors. Ethnic tensions persisted—Berbers revolted in 937, nearly fracturing the emirate. Plagues and famines struck, but resilience prevailed. By the 10th century, Sicily exported goods to Egypt and Spain, becoming a cultural bridge. This era’s innovations, like papermaking from Arab techniques, spread to Europe, aiding the Renaissance centuries later.

Shifting gears to the motivational side—remember, history dominates here, but let’s extract gems for today. The fall of Taormina teaches us about endurance amid adversity. The Byzantines held for 75 years against superior odds, adapting tactics and forging alliances. The Aghlabids, through persistence and innovation, turned a distant dream into reality. In our fast-paced world, where challenges like career shifts or personal setbacks loom, this saga reminds us that true change demands patience and strategy.

How can you benefit today? By applying these historical insights to your life, fostering resilience that turns obstacles into opportunities. Here’s how, with specific bullet points:

– **Cultivate Long-Term Vision Like the Aghlabids’ 75-Year Campaign**: Don’t chase quick wins; map out multi-year goals. For instance, if aiming for a career change, break it into phases: year 1 for skill-building, year 2 for networking, year 3 for application.

– **Build Defenses Against Setbacks, Inspired by Taormina’s Walls**: Identify your vulnerabilities—financial, emotional—and fortify them. Save an emergency fund equal to six months’ expenses, or practice daily mindfulness to handle stress, just as the town’s cliffs provided natural barriers.

– **Adapt Tactics Mid-Battle, as Byzantines Did with Mercenaries**: When plans falter, pivot. If a project at work stalls, seek collaborators or new tools, mirroring how defenders used diverse troops.

– **Harness Unity in Diversity, From Muslim Ethnic Blends**: Embrace team differences for innovation. In group settings, assign roles based on strengths, like Arabs using Berber raiders for speed.

– **Celebrate Small Victories, Echoing Post-Siege Rebuilding**: After hurdles, reflect and reward. Journal wins weekly, akin to Palermo’s renaissance under new rule.

To implement this, follow this practical plan:

- **Assess Your Current ‘Fortress’ (Week 1)**: List life challenges and strengths. Journal for 15 minutes daily, noting what ‘sieges’ you’re facing.

- **Set a 75-Day Challenge (Weeks 2-12)**: Mimic the conquest’s duration in mini-form. Choose one goal (e.g., fitness), break into daily actions—walk 10,000 steps, track progress.

- **Build Alliances (Month 2)**: Network with mentors or peers, like Euphemius seeking aid. Join a group or online community related to your goal.

- **Adapt and Innovate (Month 3)**: Review progress; adjust if needed. Introduce new habits, such as reading history books for inspiration.

- **Conquer and Reflect (Ongoing)**: Achieve the goal, then apply lessons to bigger pursuits. Celebrate with a ‘victory feast’—a fun outing—to reinforce motivation.

This ancient drama isn’t just dusty facts; it’s a blueprint for triumph. By channeling Taormina’s spirit, you’ll navigate modern battles with grit and grace.