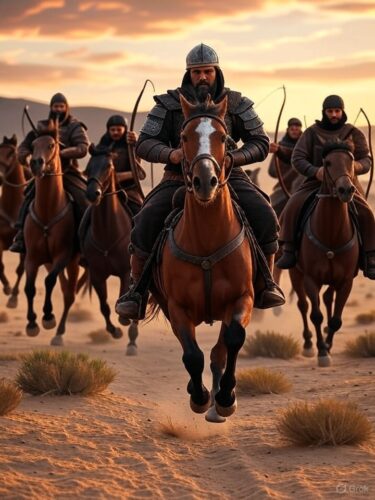

Imagine a scorching summer day in 1148, where the sun beats down on the ancient walls of Damascus like a relentless hammer. Thousands of armored knights, their banners fluttering in the hot wind, stare at the city’s formidable defenses, dreaming of glory and conquest. But by July 28, those dreams shatter into a chaotic retreat, marking one of history’s most spectacular flops. This wasn’t just any battle; it was the climax of the Second Crusade, a grand European expedition that promised to reclaim the Holy Land but ended in embarrassment and long-term consequences for the Christian and Muslim worlds alike. Today, on the anniversary of that fateful withdrawal, we’re diving deep into this underrated chapter of distant history. Not only will we unpack the drama, intrigue, and blunders that defined the Siege of Damascus, but we’ll also extract timeless gems from its ruins—lessons that can supercharge your personal growth, career, or relationships in the modern world. Get ready for a rollercoaster of knights, kings, betrayals, and battlefield mayhem, all served with a side of inspiration to make your own life a victorious crusade.

The story of the Siege of Damascus doesn’t start in 1148; it roots back in the turbulent soil of the Crusades, a series of religious wars that gripped the medieval world from the late 11th century. The First Crusade, launched in 1095 by Pope Urban II, had been a surprising success. European knights, motivated by faith, land, and adventure, captured Jerusalem in 1099 after a brutal siege, establishing Christian states like the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, and the Principality of Antioch. These “Outremer” holdings were fragile outposts in a sea of Muslim territories, relying on constant reinforcements from Europe and uneasy truces with local rulers.

By the 1140s, the tide was turning. The Muslim world, fragmented after the fall of the Fatimid Caliphate, began unifying under dynamic leaders like Imad ad-Din Zengi, the atabeg (governor) of Mosul and Aleppo. Zengi was a force of nature—a skilled warrior and administrator who dreamed of jihad against the infidels. In December 1144, he struck a devastating blow by capturing Edessa, the northernmost Crusader state. The fall of Edessa sent shockwaves through Europe. It was the first major Christian territory lost since the Crusades began, exposing the vulnerability of the Holy Land. Pope Eugene III responded with the bull *Quantum praedecessores* in December 1145, calling for a new crusade to reclaim Edessa and bolster the East.

The call resonated across Europe. Leading the charge were two powerhouse monarchs: King Louis VII of France, a pious but inexperienced young ruler eager to atone for his sins (including a scandalous burning of a church during a feud), and Emperor Conrad III of the Holy Roman Empire, a battle-hardened veteran from the German nobility. Louis was joined by his fiery wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, whose presence added glamour and gossip—she brought her own entourage and reportedly dressed as an Amazon during the march. Bernard of Clairvaux, the charismatic abbot and preacher, toured France and Germany, whipping up enthusiasm with sermons that painted the crusade as a divine duty. Thousands signed up, from nobles to peasants, swelling the armies to tens of thousands.

The journey to the Holy Land was a comedy of errors mixed with tragedy—think *Monty Python* meets *Game of Thrones*. Conrad’s German army departed first in May 1147, marching through Hungary and into Byzantine territory. The Byzantines, wary of these “barbarian” allies who had sacked Constantinople in previous crusades, provided minimal support. Tensions boiled over when German troops clashed with Byzantine forces near Constantinople. Crossing into Anatolia, controlled by the Seljuk Turks, Conrad’s army suffered ambushes and starvation. At the Battle of Dorylaeum in October 1147, the Turks nearly annihilated the Germans; Conrad escaped with just a fraction of his force, humiliated and ill.

Louis’s French army followed in June 1147, taking a similar route. They fared slightly better but still endured hardships: food shortages, disease, and skirmishes. Eleanor’s rumored affair with her uncle, Raymond of Antioch, added personal drama—Louis grew jealous, straining their marriage (which would later end in divorce, reshaping European dynasties). By early 1148, both kings arrived in the Holy Land, their armies depleted but spirits high. They linked up with local Crusader leaders, including King Baldwin III of Jerusalem, a 17-year-old prodigy ruling under his mother’s regency, and the military orders like the Knights Templar and Hospitaller.

Now, why Damascus? The original goal was Edessa, but by 1148, Zengi’s son, Nur ad-Din, had solidified control there, making recapture impractical. At the Council of Acre on June 24, 1148, held in the coastal city of Acre, the leaders debated targets. Aleppo, Nur ad-Din’s base, was tempting but heavily fortified. Damascus, however, was a jewel: the ancient city, known as the “Pearl of the East,” was a cultural and economic hub with lush orchards, grand mosques, and strategic importance. Ruled by the Burid dynasty under Mujir ad-Din Abaq and his regent Mu’in ad-Din Unur, Damascus had historically allied with Jerusalem against Zengi. But recent shifts—Unur’s overtures to Nur ad-Din after a failed Crusader attack on Bosra in 1147—made it a perceived threat.

The council, attended by Conrad, Louis, Baldwin, and barons like Thierry of Flanders and Everard des Barres (Grand Master of the Templars), voted to strike Damascus. It was a bold, perhaps foolhardy choice. Damascus wasn’t aggressively hostile, and attacking it could push it into Nur ad-Din’s arms, unifying Muslim Syria. But the Crusaders saw it as a holy prize, second only to Jerusalem, and a way to expand their territories. With an estimated 50,000 troops—knights, infantry, archers, and siege engineers—they marched from Galilee, arriving at Damascus on July 23.

The city was no pushover. Founded in the 3rd millennium BC, Damascus boasted thick stone walls, towers, and gates, surrounded by the Barada River and fertile Ghouta orchards that provided natural defenses. Unur, a shrewd Turkish mamluk, had prepared: he rallied the ahdath (urban militia), professional soldiers, and Turkoman mercenaries, totaling around 10,000-20,000 defenders. He also sent urgent pleas for help to Nur ad-Din and his brother Saif ad-Din in Aleppo and Mosul.

The siege kicked off on July 24 with the Crusaders approaching from the west, through the Ghouta orchards. This seemed smart—the trees offered cover, fruit for food, and wood for siege equipment. Baldwin led the vanguard, Louis the center, Conrad the rearguard. But the orchards turned into a nightmare labyrinth. Defenders ambushed from behind walls and towers, showering arrows and launching hit-and-run attacks. The fighting was brutal, hand-to-hand in the dense foliage. Conrad, wielding a massive sword, legendarily cleaved a Turkoman in half, boosting morale. By evening, the Crusaders crossed the Barada, capturing suburbs like al-Midmar and setting up camp, building palisades from felled trees.

July 25 saw fierce counterattacks. Unur’s forces, reinforced by volunteers from Beirut and the Bekaa Valley, charged the camp. Key Muslim commanders fell, including the scholar Yusuf al-Findalawi and a relative of Saladin (yes, that Saladin, who was a boy at the time but whose family was involved). The Crusaders held, inflicting heavy losses, but their own casualties mounted. Supplies dwindled as defenders poisoned wells and burned orchards.

On July 26, reinforcements trickled in for Damascus—archers from Lebanon and scouts from Saif ad-Din. The Crusaders, sensing stagnation, debated strategy. Rumors swirled of betrayal: some local barons, fearing Thierry of Flanders would claim Damascus (as promised by Louis), allegedly took bribes from Unur to sabotage the effort. Internal squabbles erupted—who gets the city? The Franks (Europeans) vs. the Poulains (local Crusaders) clashed over priorities.

By July 27, the Crusaders made a fatal move: shifting camp to the eastern plains, opposite Bab Sharqi and Bab Tuma gates. The walls were weaker there, but the terrain was barren—no food, little water, exposed to harassment. Why the shift? Historians debate—perhaps bad advice from locals or misinformation about reinforcements. William of Tyre, the chronicler and archbishop, blamed “treachery” by Unur’s agents spreading false intel.

The relocation was disastrous. Exposed, the army suffered constant arrow volleys. Morale plummeted as news arrived of Nur ad-Din’s army approaching from the north. On July 28, just four days in, the leaders called it quits. The retreat to Jerusalem was a harrowing gauntlet of Turkoman raids, with stragglers picked off. The Crusaders lost perhaps thousands, though exact numbers are unknown; Damascus celebrated a miraculous victory.

The aftermath was profound. The Second Crusade fizzled out—no gains, just recriminations. Louis lingered in the Holy Land until 1149, funding defenses, while Conrad sailed home earlier, his reputation tarnished. Eleanor divorced Louis in 1152, marrying Henry II of England and birthing a new dynasty. For the Muslims, the siege unified them: Unur died in 1149, and by 1154, Nur ad-Din seized Damascus, creating a powerful Syrian state. This paved the way for Saladin’s rise, who would recapture Jerusalem in 1187, sparking the Third Crusade.

The failure echoed through history. It discredited crusading in Europe, making future calls harder. Bernard of Clairvaux apologized for the debacle, blaming human sin. The Crusader states, weakened, survived another 40 years but were on borrowed time. Damascus, spared, flourished as a center of learning and trade, its Umayyad Mosque standing as a symbol of resilience.

Fun fact: During the siege, a young Saladin’s father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub, fought for Damascus, forging alliances that shaped his son’s future empire. Another anecdote: Conrad’s heroic charge inspired ballads, but his illness forced him to be carried on a litter—royalty wasn’t always glamorous. The orchards, meant for sustenance, became deathtraps, a ironic twist on the Garden of Eden imagery often invoked in Crusade propaganda.

This siege wasn’t just a military blunder; it was a human drama of ambition, ego, and miscalculation. Overconfidence met reality, and history pivoted. Now, let’s flip the script—how can this ancient flop fuel your modern wins?

While the historical saga of Damascus teaches us volumes about medieval warfare and geopolitics, its real gold lies in the life lessons buried in the sand. The Crusaders’ defeat stemmed from disunity, poor adaptability, and flawed planning—pitfalls we all face today. But by flipping these failures, you can craft a personal strategy for success. Here’s how this 1148 event translates to your life, with specific applications to turn history into motivation.

– **Embrace Thorough Preparation to Avoid Costly Missteps**: The Crusaders chose Damascus without scouting alternatives, leading to logistical nightmares. In your life, this means researching big decisions deeply. For instance, before switching jobs, don’t just eye the salary—analyze company culture, growth opportunities, and market trends like the Crusaders should have scouted the eastern plains.

– **Foster Genuine Unity in Your Teams and Relationships**: Internal bickering over spoils doomed the siege. Apply this by building trust in your circles. In a group project at work, assign roles clearly and celebrate collective wins, avoiding the “who gets the credit” drama that fractured the kings’ alliance.

– **Adapt Swiftly to Changing Circumstances**: The shift to the east was a knee-jerk reaction to pressure. Today, cultivate flexibility— if a fitness goal hits a plateau, pivot your routine with new exercises or a coach, rather than stubbornly sticking to a failing plan like the orchard strategy.

– **Beware of External Influences and Stay True to Your Goals**: Rumors and bribes swayed the Crusaders. Guard against this by seeking unbiased advice. When investing, ignore hype from social media “gurus” and rely on verified data, ensuring your path isn’t derailed like the siege by alleged traitors.

– **Learn from Setbacks to Build Resilience**: The retreat humiliated the leaders, but it spurred reforms in the Holy Land. Turn your failures into fuel—after a failed business pitch, journal what went wrong and refine your approach, emerging stronger like Nur ad-Din did post-siege.

To make this actionable, here’s a step-by-step plan inspired by the siege’s lessons. Follow it over 30 days to conquer your own “Damascus”—that big goal you’ve been eyeing.

- **Days 1-5: Define Your Target and Scout the Terrain**: Identify a specific objective, like landing a promotion or starting a side hustle. Research extensively—list pros, cons, resources needed, and potential obstacles. Journal daily, asking: “What ‘orchards’ (advantages) and ‘walls’ (barriers) await?”

- **Days 6-10: Assemble Your Alliance**: Rally supporters—friends, mentors, or colleagues. Schedule meetings to align on roles and shared vision. Build trust with open communication, avoiding the Crusaders’ ego clashes by emphasizing mutual benefits.

- **Days 11-20: Launch Your Assault with a Solid Strategy**: Execute your plan in phases. Break it into daily actions, like networking for that job or prototyping your business idea. Monitor progress and adapt— if something falters, pivot quickly without abandoning the core goal.

- **Days 21-25: Defend Against Distractions**: Anticipate setbacks, like doubts or external noise. Use affirmations rooted in history: “Like Damascus standing firm, I’ll endure.” Track wins to maintain morale, and seek feedback to counter “rumors” of failure.

- **Days 26-30: Reflect and Reinforce**: Evaluate outcomes. Celebrate successes, analyze misses, and plan next steps. If you “fail,” retreat strategically—regroup and relaunch, turning the experience into a foundation for future triumphs, just as the siege’s lessons echoed through centuries.

By channeling the Siege of Damascus, you’re not just learning history; you’re wielding it as a weapon for personal victory. This event reminds us that even epic failures birth opportunities—if you’re bold enough to seize them. So, charge forward; your conquest awaits!