Imagine a world where the fate of an empire hinges on a single, blood-soaked showdown in the misty valleys of ancient Gaul. No, this isn't the plot of some over-the-top gladiator flick—though it could be, complete with betrayals, horse charges, and enough drama to make Julius Caesar blush. We're talking about the Battle of Lugdunum, fought on February 19, 197 AD, a colossal Roman civil war brawl that decided who got to wear the purple toga and rule the known world. This wasn't just any skirmish; it was the deadliest clash between Roman armies ever recorded, with up to 150,000 soldiers hacking away at each other like they had a personal grudge against the concept of peace. And yet, amid the clanging swords and flying arrows, there are lessons in grit, strategy, and sheer audacity that could turn your everyday hurdles into triumphs. But before we get to the motivational pep talk (because, let's face it, who doesn't need a Roman emperor's playbook for adulting?), let's dive deep into the history—90% deep, to be precise. Buckle up; this is going to be a wild, educational ride through the Roman Empire's most chaotic year, with a dash of humor to keep things from getting as grim as a defeated legionnaire's diary. To understand why February 19, 197 AD, turned into a Roman apocalypse, we have to rewind to the messy soap opera that was the Year of the Five Emperors in 193 AD. Picture this: The Roman Empire, that sprawling beast stretching from foggy Britain to sunny Syria, was already teetering like a chariot on a bad axle. Emperor Commodus—yes, the one Joaquin Phoenix played in *Gladiator*, but way less charismatic in real life—had just been strangled in his bath on New Year's Eve 192 AD. Commodus was a disaster: He fancied himself a gladiator god, renamed Rome after himself (Colonia Commodiana, anyone?), and basically turned the empire into his personal ego trip. His death left a power vacuum bigger than the Colosseum, and the Praetorian Guard—the elite bodyguards who were supposed to protect the emperor but often acted like a mafia—decided to auction off the throne. Literally. On March 28, 193 AD, after murdering the short-lived Emperor Pertinax (who lasted a whopping 87 days because he tried to reform the corrupt guards), they put the empire up for bid. The winner? Didius Julianus, a rich senator who shelled out 25,000 sesterces per guard—think of it as buying the presidency with cryptocurrency bribes. The Roman people were furious; they threw stones and insults at Julianus, calling him a "parricide" for essentially buying a stolen crown.

Enter the contenders, because nothing says "stable government" like five guys claiming to be emperor at once. First up: Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria. He was a no-nonsense military man with a reputation for discipline—his troops loved him, and he controlled nine legions in the East. The crowds in Rome chanted his name, hoping he'd swoop in and fix the mess. But geography was against him; Syria was a long march from the capital. Meanwhile, in Pannonia Superior (modern Hungary and Austria), Septimius Severus was plotting. Severus was a tough cookie from Leptis Magna in North Africa—think of him as the empire's scrappy underdog with a chip on his shoulder. He commanded three legions and had a knack for alliances. His troops proclaimed him emperor on April 9, 193 AD, and he immediately promised to avenge Pertinax, which won him brownie points with the army. But Severus was smart; he knew he couldn't fight everyone at once. So, he cut a deal with Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britannia. Albinus was a blue-blooded Roman from Hadrumetum (Tunisia), commanding three legions and a bunch of auxiliaries—about 40,000 men total. Severus named him Caesar (basically junior emperor and heir), and Albinus bit, staying put in Britain while Severus marched on Rome.

Severus moved fast—like, Roman express delivery fast. By June 193 AD, he was at Rome's gates. Julianus panicked, tried to negotiate, and ended up beheaded by his own guards. The Senate, ever the opportunists, hailed Severus as emperor. But Severus wasn't done housecleaning; he disbanded the entire Praetorian Guard (about 10,000 men) and replaced them with his loyal Danubian troops. It was a bold move—imagine firing the Secret Service and hiring your poker buddies instead. With Rome secure, Severus turned east to deal with Niger. He sent his generals ahead, and battles erupted across Asia Minor. At Cyzicus and Nicaea, Severus's forces chipped away at Niger's support. The decisive blow came at the Battle of Issus in 194 AD—ironically the same spot where Alexander the Great crushed the Persians centuries earlier. Niger's army crumbled; he fled to Antioch, got captured, and lost his head. Severus, ever the showman, paraded it around like a trophy.

To understand why February 19, 197 AD, turned into a Roman apocalypse, we have to rewind to the messy soap opera that was the Year of the Five Emperors in 193 AD. Picture this: The Roman Empire, that sprawling beast stretching from foggy Britain to sunny Syria, was already teetering like a chariot on a bad axle. Emperor Commodus—yes, the one Joaquin Phoenix played in *Gladiator*, but way less charismatic in real life—had just been strangled in his bath on New Year's Eve 192 AD. Commodus was a disaster: He fancied himself a gladiator god, renamed Rome after himself (Colonia Commodiana, anyone?), and basically turned the empire into his personal ego trip. His death left a power vacuum bigger than the Colosseum, and the Praetorian Guard—the elite bodyguards who were supposed to protect the emperor but often acted like a mafia—decided to auction off the throne. Literally. On March 28, 193 AD, after murdering the short-lived Emperor Pertinax (who lasted a whopping 87 days because he tried to reform the corrupt guards), they put the empire up for bid. The winner? Didius Julianus, a rich senator who shelled out 25,000 sesterces per guard—think of it as buying the presidency with cryptocurrency bribes. The Roman people were furious; they threw stones and insults at Julianus, calling him a "parricide" for essentially buying a stolen crown.

Enter the contenders, because nothing says "stable government" like five guys claiming to be emperor at once. First up: Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria. He was a no-nonsense military man with a reputation for discipline—his troops loved him, and he controlled nine legions in the East. The crowds in Rome chanted his name, hoping he'd swoop in and fix the mess. But geography was against him; Syria was a long march from the capital. Meanwhile, in Pannonia Superior (modern Hungary and Austria), Septimius Severus was plotting. Severus was a tough cookie from Leptis Magna in North Africa—think of him as the empire's scrappy underdog with a chip on his shoulder. He commanded three legions and had a knack for alliances. His troops proclaimed him emperor on April 9, 193 AD, and he immediately promised to avenge Pertinax, which won him brownie points with the army. But Severus was smart; he knew he couldn't fight everyone at once. So, he cut a deal with Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britannia. Albinus was a blue-blooded Roman from Hadrumetum (Tunisia), commanding three legions and a bunch of auxiliaries—about 40,000 men total. Severus named him Caesar (basically junior emperor and heir), and Albinus bit, staying put in Britain while Severus marched on Rome.

Severus moved fast—like, Roman express delivery fast. By June 193 AD, he was at Rome's gates. Julianus panicked, tried to negotiate, and ended up beheaded by his own guards. The Senate, ever the opportunists, hailed Severus as emperor. But Severus wasn't done housecleaning; he disbanded the entire Praetorian Guard (about 10,000 men) and replaced them with his loyal Danubian troops. It was a bold move—imagine firing the Secret Service and hiring your poker buddies instead. With Rome secure, Severus turned east to deal with Niger. He sent his generals ahead, and battles erupted across Asia Minor. At Cyzicus and Nicaea, Severus's forces chipped away at Niger's support. The decisive blow came at the Battle of Issus in 194 AD—ironically the same spot where Alexander the Great crushed the Persians centuries earlier. Niger's army crumbled; he fled to Antioch, got captured, and lost his head. Severus, ever the showman, paraded it around like a trophy. With the East pacified, Severus could have chilled with some wine and olives, but no—ambition called. In 195 AD, he campaigned against the Parthians, sacking cities and annexing territories. To legitimize his rule, he pulled a PR stunt: He retroactively adopted himself into the Antonine dynasty, claiming to be the son of Marcus Aurelius (the philosopher-emperor) and brother of Commodus. It was fake news, Roman style, but it worked. He even renamed his son Bassianus to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus—better known as Caracalla—and made him Caesar. This was a slap in the face to Albinus, who thought he was the heir. Albinus, feeling ghosted, declared himself Augustus in late 196 AD and crossed the Channel to Gaul with his Britannic legions. He set up shop in Lugdunum, the bustling capital of Lugdunensis province, a city of aqueducts, theaters, and about 50,000 residents. It was strategically perfect: Close to Italy, with good roads and rivers for supplies.

The stage was set for civil war. Albinus tried to soften Severus up by attacking his allies in Germania. He clashed with Virius Lupus, governor of Germania Inferior, and won some ground but not enough to flip loyalties. An invasion of Italy was tempting, but Severus had fortified the Alpine passes like a Roman Fort Knox. Winter 196-197 AD was tense; both sides mustered forces. Severus drew from the Danube, Illyricum, Moesia, and Dacia—tough, battle-hardened legions used to frontier fights. Albinus had his British troops, plus Legio VII Gemina from Hispania under Lucius Novius Rufus. Estimates vary, but each army hovered around 50,000-75,000 men, making this the Super Bowl of Roman battles.

With the East pacified, Severus could have chilled with some wine and olives, but no—ambition called. In 195 AD, he campaigned against the Parthians, sacking cities and annexing territories. To legitimize his rule, he pulled a PR stunt: He retroactively adopted himself into the Antonine dynasty, claiming to be the son of Marcus Aurelius (the philosopher-emperor) and brother of Commodus. It was fake news, Roman style, but it worked. He even renamed his son Bassianus to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus—better known as Caracalla—and made him Caesar. This was a slap in the face to Albinus, who thought he was the heir. Albinus, feeling ghosted, declared himself Augustus in late 196 AD and crossed the Channel to Gaul with his Britannic legions. He set up shop in Lugdunum, the bustling capital of Lugdunensis province, a city of aqueducts, theaters, and about 50,000 residents. It was strategically perfect: Close to Italy, with good roads and rivers for supplies.

The stage was set for civil war. Albinus tried to soften Severus up by attacking his allies in Germania. He clashed with Virius Lupus, governor of Germania Inferior, and won some ground but not enough to flip loyalties. An invasion of Italy was tempting, but Severus had fortified the Alpine passes like a Roman Fort Knox. Winter 196-197 AD was tense; both sides mustered forces. Severus drew from the Danube, Illyricum, Moesia, and Dacia—tough, battle-hardened legions used to frontier fights. Albinus had his British troops, plus Legio VII Gemina from Hispania under Lucius Novius Rufus. Estimates vary, but each army hovered around 50,000-75,000 men, making this the Super Bowl of Roman battles. The preliminaries kicked off at Tinurtium (modern Tournus), about 60 miles north of Lugdunum. Severus's vanguard clashed with Albinus's forces in a brutal scrum. Details are fuzzy—ancient historians like Cassius Dio and Herodian weren't embedded reporters—but Severus edged out a win, forcing Albinus to retreat south. Severus pursued relentlessly, his cavalry scouting ahead. By February 19, 197 AD, the armies faced off on the plains outside Lugdunum. The date was no accident; winter campaigns were rare, but Severus wanted to end this before Albinus could rally more support.

Dawn broke cold and foggy—perfect for ambushes and dramatic entrances. The armies lined up in classic Roman fashion: Infantry in the center, cavalry on the flanks, auxiliaries peppering the lines. Severus's forces included Pannonian and Moesian legions—veterans of Parthian wars—while Albinus had the disciplined Brits, known for their heavy infantry and Celtic flair. The battle raged for two days, which was unheard of; most Roman fights wrapped up by lunch. Wave after wave crashed: Spears flew, shields bashed, swords sliced. Imagine the noise—a cacophony of war cries, trumpet blasts, and the thud of catapults launching rocks. At one point, Albinus's left flank buckled, but his center held like a stubborn mule. Severus, sensing weakness, committed his cavalry—Praetorian horsemen and Moorish light cavalry—in a flanking maneuver. It was a game-changer; the horses thundered in, trampling Albinus's exposed side.

Humor break: Picture Severus, this African-born general with a beard that screamed "I'm in charge," yelling orders while his troops wondered if they'd get hazard pay. And Albinus? Probably regretting not staying in rainy Britain with a nice cup of herbal tea. The fighting was so intense that rivers ran red—literally, as the Rhone nearby got a gruesome dye job. Cassius Dio called it the bloodiest battle between Romans, with casualties possibly topping 100,000. That's like wiping out a modern city's population in 48 hours. By dusk on the second day, Albinus's lines shattered. His men fled into Lugdunum, but there was no escape.

Albinus barricaded himself in a house, but as Severus's troops closed in, he chose the dramatic exit: Suicide by sword. Severus, not one for half-measures, had the body stripped, beheaded, and trampled by his horse—a real "victory lap." The head went to Rome on a pike as a warning: Don't mess with the new boss. Albinus's wife and sons? Executed and tossed in the Rhone. Harsh? Absolutely. But in Roman politics, mercy was for losers. Severus then purged the Senate, executing 29 pro-Albinus senators and confiscating their estates—funding his regime like a ancient Ponzi scheme.

The aftermath reshaped the empire. Lugdunum, once Albinus's HQ, got a makeover. Severus revamped the Imperial cult sanctuary there, turning it into a symbol of his dominance. The rituals shifted to emphasize the emperor as a master over slaves—subtle, huh? Britain, stripped of troops, split into two provinces: Britannia Superior and Inferior, to prevent future rebellions. The legions were weakened, leading to barbarian incursions and a retreat from the Antonine Wall back to Hadrian's. Severus ruled until 211 AD, dying in York (Eboracum) while campaigning against Scottish tribes—ironic, since Albinus's old turf bit him in the end. His dynasty lasted until 235 AD, bringing stability but also paranoia and purges.

The preliminaries kicked off at Tinurtium (modern Tournus), about 60 miles north of Lugdunum. Severus's vanguard clashed with Albinus's forces in a brutal scrum. Details are fuzzy—ancient historians like Cassius Dio and Herodian weren't embedded reporters—but Severus edged out a win, forcing Albinus to retreat south. Severus pursued relentlessly, his cavalry scouting ahead. By February 19, 197 AD, the armies faced off on the plains outside Lugdunum. The date was no accident; winter campaigns were rare, but Severus wanted to end this before Albinus could rally more support.

Dawn broke cold and foggy—perfect for ambushes and dramatic entrances. The armies lined up in classic Roman fashion: Infantry in the center, cavalry on the flanks, auxiliaries peppering the lines. Severus's forces included Pannonian and Moesian legions—veterans of Parthian wars—while Albinus had the disciplined Brits, known for their heavy infantry and Celtic flair. The battle raged for two days, which was unheard of; most Roman fights wrapped up by lunch. Wave after wave crashed: Spears flew, shields bashed, swords sliced. Imagine the noise—a cacophony of war cries, trumpet blasts, and the thud of catapults launching rocks. At one point, Albinus's left flank buckled, but his center held like a stubborn mule. Severus, sensing weakness, committed his cavalry—Praetorian horsemen and Moorish light cavalry—in a flanking maneuver. It was a game-changer; the horses thundered in, trampling Albinus's exposed side.

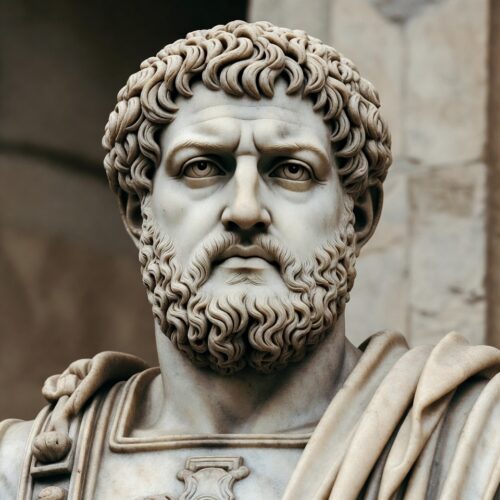

Humor break: Picture Severus, this African-born general with a beard that screamed "I'm in charge," yelling orders while his troops wondered if they'd get hazard pay. And Albinus? Probably regretting not staying in rainy Britain with a nice cup of herbal tea. The fighting was so intense that rivers ran red—literally, as the Rhone nearby got a gruesome dye job. Cassius Dio called it the bloodiest battle between Romans, with casualties possibly topping 100,000. That's like wiping out a modern city's population in 48 hours. By dusk on the second day, Albinus's lines shattered. His men fled into Lugdunum, but there was no escape.

Albinus barricaded himself in a house, but as Severus's troops closed in, he chose the dramatic exit: Suicide by sword. Severus, not one for half-measures, had the body stripped, beheaded, and trampled by his horse—a real "victory lap." The head went to Rome on a pike as a warning: Don't mess with the new boss. Albinus's wife and sons? Executed and tossed in the Rhone. Harsh? Absolutely. But in Roman politics, mercy was for losers. Severus then purged the Senate, executing 29 pro-Albinus senators and confiscating their estates—funding his regime like a ancient Ponzi scheme.

The aftermath reshaped the empire. Lugdunum, once Albinus's HQ, got a makeover. Severus revamped the Imperial cult sanctuary there, turning it into a symbol of his dominance. The rituals shifted to emphasize the emperor as a master over slaves—subtle, huh? Britain, stripped of troops, split into two provinces: Britannia Superior and Inferior, to prevent future rebellions. The legions were weakened, leading to barbarian incursions and a retreat from the Antonine Wall back to Hadrian's. Severus ruled until 211 AD, dying in York (Eboracum) while campaigning against Scottish tribes—ironic, since Albinus's old turf bit him in the end. His dynasty lasted until 235 AD, bringing stability but also paranoia and purges. Why does this matter? The Battle of Lugdunum wasn't just a power grab; it highlighted Rome's fragility. The Year of the Five Emperors showed how the army, not the Senate, picked rulers—foreshadowing the third-century crisis. Severus's African origins diversified the empire's leadership, proving outsiders could rule. Economically, the war drained treasuries, leading to currency debasement and inflation—sound familiar? Militarily, it showcased cavalry's rising importance, evolving from infantry dominance. Culturally, Lugdunum thrived post-battle as a trade hub, its aqueducts and forums buzzing with life. Fun fact: The city's Fourvière hill still holds ruins from that era, whispering tales of glory and gore.

Expanding on the players: Septimius Severus was a family man—sort of. He married Julia Domna, a Syrian priestess whose intellect rivaled any senator's. She influenced policy, earning the title "Mother of the Camps." Clodius Albinus? A cultured guy who minted coins showing himself as a liberator—propaganda 101. The legions involved were legends: Severus's Legio XIV Gemina, victors over Parthians; Albinus's Legio VI Victrix, fresh from Hadrian's Wall. Training was grueling—marches with 60-pound packs, sword drills till blisters formed. Diet? Porridge, bacon, and sour wine—glamorous, right?

The battle's tactics? Likely a mix of testudo formations (shields like a turtle shell) and pilum volleys (javelins that bent on impact, ruining enemy shields). Cavalry charges, led by equites in plumed helmets, turned the tide—think knights before knights were cool. Weather played a role; February in Gaul is chilly, with mud slowing chariots. Casualties were horrific; no Geneva Convention here—wounded were often finished off. Survivors got spoils: Armor, slaves, land grants.

Post-Lugdunum, Severus reformed the army, increasing pay and allowing marriages—boosting morale but straining budgets. He built the Arch of Severus in Rome, still standing, depicting his triumphs. In Africa, he funded Leptis Magna's grandeur—columns, baths, the works. The war's ripple: Parthian weakness invited later invasions, while Britain's division quelled revolts but exposed frontiers.

Why does this matter? The Battle of Lugdunum wasn't just a power grab; it highlighted Rome's fragility. The Year of the Five Emperors showed how the army, not the Senate, picked rulers—foreshadowing the third-century crisis. Severus's African origins diversified the empire's leadership, proving outsiders could rule. Economically, the war drained treasuries, leading to currency debasement and inflation—sound familiar? Militarily, it showcased cavalry's rising importance, evolving from infantry dominance. Culturally, Lugdunum thrived post-battle as a trade hub, its aqueducts and forums buzzing with life. Fun fact: The city's Fourvière hill still holds ruins from that era, whispering tales of glory and gore.

Expanding on the players: Septimius Severus was a family man—sort of. He married Julia Domna, a Syrian priestess whose intellect rivaled any senator's. She influenced policy, earning the title "Mother of the Camps." Clodius Albinus? A cultured guy who minted coins showing himself as a liberator—propaganda 101. The legions involved were legends: Severus's Legio XIV Gemina, victors over Parthians; Albinus's Legio VI Victrix, fresh from Hadrian's Wall. Training was grueling—marches with 60-pound packs, sword drills till blisters formed. Diet? Porridge, bacon, and sour wine—glamorous, right?

The battle's tactics? Likely a mix of testudo formations (shields like a turtle shell) and pilum volleys (javelins that bent on impact, ruining enemy shields). Cavalry charges, led by equites in plumed helmets, turned the tide—think knights before knights were cool. Weather played a role; February in Gaul is chilly, with mud slowing chariots. Casualties were horrific; no Geneva Convention here—wounded were often finished off. Survivors got spoils: Armor, slaves, land grants.

Post-Lugdunum, Severus reformed the army, increasing pay and allowing marriages—boosting morale but straining budgets. He built the Arch of Severus in Rome, still standing, depicting his triumphs. In Africa, he funded Leptis Magna's grandeur—columns, baths, the works. The war's ripple: Parthian weakness invited later invasions, while Britain's division quelled revolts but exposed frontiers. Now, for that 10% motivational magic: How does this ancient slugfest benefit you today? The Battle of Lugdunum screams resilience—Severus turned betrayal into empire-building. In your life, channel that by turning setbacks into setups. Here's how, with specific bullet points and a plan:

- **Embrace Strategic Alliances, But Know When to Pivot:** Severus allied with Albinus temporarily, then adapted. In your career, network wisely—collaborate on projects, but if goals shift, reassess without burning bridges. Benefit: Stronger professional relationships lead to promotions or side hustles.

- **Turn Outsider Status into Strength:** As an African in a Roman world, Severus used his unique perspective to outmaneuver rivals. Apply this by leveraging your background in job interviews or startups—diverse views spark innovation, boosting confidence and opportunities.

- **Master the Long Game in Adversity:** The two-day battle tested endurance; Severus won by persistence. For personal fitness, commit to daily walks escalating to runs—benefit: Improved health, mental clarity, and that "I conquered" glow.

- **Learn from Failures Without Mercy-Killing Your Dreams:** Albinus's defeat was total, but imagine if he'd retreated earlier. In relationships, analyze breakups for patterns, then date intentionally—result: Healthier connections, less heartbreak.

The Plan: Week 1—Research your "battle": Journal past challenges like Severus's rivals. Week 2—Build your "legions": Network with three mentors. Week 3—Charge ahead: Set a goal (e.g., skill course) and persist daily. Week 4—Celebrate victories: Reward progress, reflect on growth. Repeat, and watch your life transform from chaos to conquest. There you have it—history's raw power, served with a side of inspiration. Who knew a 1,800-year-old bloodbath could be your secret weapon?

Now, for that 10% motivational magic: How does this ancient slugfest benefit you today? The Battle of Lugdunum screams resilience—Severus turned betrayal into empire-building. In your life, channel that by turning setbacks into setups. Here's how, with specific bullet points and a plan:

- **Embrace Strategic Alliances, But Know When to Pivot:** Severus allied with Albinus temporarily, then adapted. In your career, network wisely—collaborate on projects, but if goals shift, reassess without burning bridges. Benefit: Stronger professional relationships lead to promotions or side hustles.

- **Turn Outsider Status into Strength:** As an African in a Roman world, Severus used his unique perspective to outmaneuver rivals. Apply this by leveraging your background in job interviews or startups—diverse views spark innovation, boosting confidence and opportunities.

- **Master the Long Game in Adversity:** The two-day battle tested endurance; Severus won by persistence. For personal fitness, commit to daily walks escalating to runs—benefit: Improved health, mental clarity, and that "I conquered" glow.

- **Learn from Failures Without Mercy-Killing Your Dreams:** Albinus's defeat was total, but imagine if he'd retreated earlier. In relationships, analyze breakups for patterns, then date intentionally—result: Healthier connections, less heartbreak.

The Plan: Week 1—Research your "battle": Journal past challenges like Severus's rivals. Week 2—Build your "legions": Network with three mentors. Week 3—Charge ahead: Set a goal (e.g., skill course) and persist daily. Week 4—Celebrate victories: Reward progress, reflect on growth. Repeat, and watch your life transform from chaos to conquest. There you have it—history's raw power, served with a side of inspiration. Who knew a 1,800-year-old bloodbath could be your secret weapon?

To understand why February 19, 197 AD, turned into a Roman apocalypse, we have to rewind to the messy soap opera that was the Year of the Five Emperors in 193 AD. Picture this: The Roman Empire, that sprawling beast stretching from foggy Britain to sunny Syria, was already teetering like a chariot on a bad axle. Emperor Commodus—yes, the one Joaquin Phoenix played in *Gladiator*, but way less charismatic in real life—had just been strangled in his bath on New Year's Eve 192 AD. Commodus was a disaster: He fancied himself a gladiator god, renamed Rome after himself (Colonia Commodiana, anyone?), and basically turned the empire into his personal ego trip. His death left a power vacuum bigger than the Colosseum, and the Praetorian Guard—the elite bodyguards who were supposed to protect the emperor but often acted like a mafia—decided to auction off the throne. Literally. On March 28, 193 AD, after murdering the short-lived Emperor Pertinax (who lasted a whopping 87 days because he tried to reform the corrupt guards), they put the empire up for bid. The winner? Didius Julianus, a rich senator who shelled out 25,000 sesterces per guard—think of it as buying the presidency with cryptocurrency bribes. The Roman people were furious; they threw stones and insults at Julianus, calling him a "parricide" for essentially buying a stolen crown. Enter the contenders, because nothing says "stable government" like five guys claiming to be emperor at once. First up: Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria. He was a no-nonsense military man with a reputation for discipline—his troops loved him, and he controlled nine legions in the East. The crowds in Rome chanted his name, hoping he'd swoop in and fix the mess. But geography was against him; Syria was a long march from the capital. Meanwhile, in Pannonia Superior (modern Hungary and Austria), Septimius Severus was plotting. Severus was a tough cookie from Leptis Magna in North Africa—think of him as the empire's scrappy underdog with a chip on his shoulder. He commanded three legions and had a knack for alliances. His troops proclaimed him emperor on April 9, 193 AD, and he immediately promised to avenge Pertinax, which won him brownie points with the army. But Severus was smart; he knew he couldn't fight everyone at once. So, he cut a deal with Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britannia. Albinus was a blue-blooded Roman from Hadrumetum (Tunisia), commanding three legions and a bunch of auxiliaries—about 40,000 men total. Severus named him Caesar (basically junior emperor and heir), and Albinus bit, staying put in Britain while Severus marched on Rome. Severus moved fast—like, Roman express delivery fast. By June 193 AD, he was at Rome's gates. Julianus panicked, tried to negotiate, and ended up beheaded by his own guards. The Senate, ever the opportunists, hailed Severus as emperor. But Severus wasn't done housecleaning; he disbanded the entire Praetorian Guard (about 10,000 men) and replaced them with his loyal Danubian troops. It was a bold move—imagine firing the Secret Service and hiring your poker buddies instead. With Rome secure, Severus turned east to deal with Niger. He sent his generals ahead, and battles erupted across Asia Minor. At Cyzicus and Nicaea, Severus's forces chipped away at Niger's support. The decisive blow came at the Battle of Issus in 194 AD—ironically the same spot where Alexander the Great crushed the Persians centuries earlier. Niger's army crumbled; he fled to Antioch, got captured, and lost his head. Severus, ever the showman, paraded it around like a trophy.

With the East pacified, Severus could have chilled with some wine and olives, but no—ambition called. In 195 AD, he campaigned against the Parthians, sacking cities and annexing territories. To legitimize his rule, he pulled a PR stunt: He retroactively adopted himself into the Antonine dynasty, claiming to be the son of Marcus Aurelius (the philosopher-emperor) and brother of Commodus. It was fake news, Roman style, but it worked. He even renamed his son Bassianus to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus—better known as Caracalla—and made him Caesar. This was a slap in the face to Albinus, who thought he was the heir. Albinus, feeling ghosted, declared himself Augustus in late 196 AD and crossed the Channel to Gaul with his Britannic legions. He set up shop in Lugdunum, the bustling capital of Lugdunensis province, a city of aqueducts, theaters, and about 50,000 residents. It was strategically perfect: Close to Italy, with good roads and rivers for supplies. The stage was set for civil war. Albinus tried to soften Severus up by attacking his allies in Germania. He clashed with Virius Lupus, governor of Germania Inferior, and won some ground but not enough to flip loyalties. An invasion of Italy was tempting, but Severus had fortified the Alpine passes like a Roman Fort Knox. Winter 196-197 AD was tense; both sides mustered forces. Severus drew from the Danube, Illyricum, Moesia, and Dacia—tough, battle-hardened legions used to frontier fights. Albinus had his British troops, plus Legio VII Gemina from Hispania under Lucius Novius Rufus. Estimates vary, but each army hovered around 50,000-75,000 men, making this the Super Bowl of Roman battles.

The preliminaries kicked off at Tinurtium (modern Tournus), about 60 miles north of Lugdunum. Severus's vanguard clashed with Albinus's forces in a brutal scrum. Details are fuzzy—ancient historians like Cassius Dio and Herodian weren't embedded reporters—but Severus edged out a win, forcing Albinus to retreat south. Severus pursued relentlessly, his cavalry scouting ahead. By February 19, 197 AD, the armies faced off on the plains outside Lugdunum. The date was no accident; winter campaigns were rare, but Severus wanted to end this before Albinus could rally more support. Dawn broke cold and foggy—perfect for ambushes and dramatic entrances. The armies lined up in classic Roman fashion: Infantry in the center, cavalry on the flanks, auxiliaries peppering the lines. Severus's forces included Pannonian and Moesian legions—veterans of Parthian wars—while Albinus had the disciplined Brits, known for their heavy infantry and Celtic flair. The battle raged for two days, which was unheard of; most Roman fights wrapped up by lunch. Wave after wave crashed: Spears flew, shields bashed, swords sliced. Imagine the noise—a cacophony of war cries, trumpet blasts, and the thud of catapults launching rocks. At one point, Albinus's left flank buckled, but his center held like a stubborn mule. Severus, sensing weakness, committed his cavalry—Praetorian horsemen and Moorish light cavalry—in a flanking maneuver. It was a game-changer; the horses thundered in, trampling Albinus's exposed side. Humor break: Picture Severus, this African-born general with a beard that screamed "I'm in charge," yelling orders while his troops wondered if they'd get hazard pay. And Albinus? Probably regretting not staying in rainy Britain with a nice cup of herbal tea. The fighting was so intense that rivers ran red—literally, as the Rhone nearby got a gruesome dye job. Cassius Dio called it the bloodiest battle between Romans, with casualties possibly topping 100,000. That's like wiping out a modern city's population in 48 hours. By dusk on the second day, Albinus's lines shattered. His men fled into Lugdunum, but there was no escape. Albinus barricaded himself in a house, but as Severus's troops closed in, he chose the dramatic exit: Suicide by sword. Severus, not one for half-measures, had the body stripped, beheaded, and trampled by his horse—a real "victory lap." The head went to Rome on a pike as a warning: Don't mess with the new boss. Albinus's wife and sons? Executed and tossed in the Rhone. Harsh? Absolutely. But in Roman politics, mercy was for losers. Severus then purged the Senate, executing 29 pro-Albinus senators and confiscating their estates—funding his regime like a ancient Ponzi scheme. The aftermath reshaped the empire. Lugdunum, once Albinus's HQ, got a makeover. Severus revamped the Imperial cult sanctuary there, turning it into a symbol of his dominance. The rituals shifted to emphasize the emperor as a master over slaves—subtle, huh? Britain, stripped of troops, split into two provinces: Britannia Superior and Inferior, to prevent future rebellions. The legions were weakened, leading to barbarian incursions and a retreat from the Antonine Wall back to Hadrian's. Severus ruled until 211 AD, dying in York (Eboracum) while campaigning against Scottish tribes—ironic, since Albinus's old turf bit him in the end. His dynasty lasted until 235 AD, bringing stability but also paranoia and purges.

Why does this matter? The Battle of Lugdunum wasn't just a power grab; it highlighted Rome's fragility. The Year of the Five Emperors showed how the army, not the Senate, picked rulers—foreshadowing the third-century crisis. Severus's African origins diversified the empire's leadership, proving outsiders could rule. Economically, the war drained treasuries, leading to currency debasement and inflation—sound familiar? Militarily, it showcased cavalry's rising importance, evolving from infantry dominance. Culturally, Lugdunum thrived post-battle as a trade hub, its aqueducts and forums buzzing with life. Fun fact: The city's Fourvière hill still holds ruins from that era, whispering tales of glory and gore. Expanding on the players: Septimius Severus was a family man—sort of. He married Julia Domna, a Syrian priestess whose intellect rivaled any senator's. She influenced policy, earning the title "Mother of the Camps." Clodius Albinus? A cultured guy who minted coins showing himself as a liberator—propaganda 101. The legions involved were legends: Severus's Legio XIV Gemina, victors over Parthians; Albinus's Legio VI Victrix, fresh from Hadrian's Wall. Training was grueling—marches with 60-pound packs, sword drills till blisters formed. Diet? Porridge, bacon, and sour wine—glamorous, right? The battle's tactics? Likely a mix of testudo formations (shields like a turtle shell) and pilum volleys (javelins that bent on impact, ruining enemy shields). Cavalry charges, led by equites in plumed helmets, turned the tide—think knights before knights were cool. Weather played a role; February in Gaul is chilly, with mud slowing chariots. Casualties were horrific; no Geneva Convention here—wounded were often finished off. Survivors got spoils: Armor, slaves, land grants. Post-Lugdunum, Severus reformed the army, increasing pay and allowing marriages—boosting morale but straining budgets. He built the Arch of Severus in Rome, still standing, depicting his triumphs. In Africa, he funded Leptis Magna's grandeur—columns, baths, the works. The war's ripple: Parthian weakness invited later invasions, while Britain's division quelled revolts but exposed frontiers.

Now, for that 10% motivational magic: How does this ancient slugfest benefit you today? The Battle of Lugdunum screams resilience—Severus turned betrayal into empire-building. In your life, channel that by turning setbacks into setups. Here's how, with specific bullet points and a plan: - **Embrace Strategic Alliances, But Know When to Pivot:** Severus allied with Albinus temporarily, then adapted. In your career, network wisely—collaborate on projects, but if goals shift, reassess without burning bridges. Benefit: Stronger professional relationships lead to promotions or side hustles. - **Turn Outsider Status into Strength:** As an African in a Roman world, Severus used his unique perspective to outmaneuver rivals. Apply this by leveraging your background in job interviews or startups—diverse views spark innovation, boosting confidence and opportunities. - **Master the Long Game in Adversity:** The two-day battle tested endurance; Severus won by persistence. For personal fitness, commit to daily walks escalating to runs—benefit: Improved health, mental clarity, and that "I conquered" glow. - **Learn from Failures Without Mercy-Killing Your Dreams:** Albinus's defeat was total, but imagine if he'd retreated earlier. In relationships, analyze breakups for patterns, then date intentionally—result: Healthier connections, less heartbreak. The Plan: Week 1—Research your "battle": Journal past challenges like Severus's rivals. Week 2—Build your "legions": Network with three mentors. Week 3—Charge ahead: Set a goal (e.g., skill course) and persist daily. Week 4—Celebrate victories: Reward progress, reflect on growth. Repeat, and watch your life transform from chaos to conquest. There you have it—history's raw power, served with a side of inspiration. Who knew a 1,800-year-old bloodbath could be your secret weapon?