Imagine a world where empires rise and crumble not on the clash of swords alone, but on the whisper of a winter wind freezing a mighty river just long enough for destiny to strike. Picture vast steppes dusted in frost, where nomadic horsemen—fierce, unyielding descendants of ancient wanderers—turn the tide of history with cunning rather than sheer numbers. This is no tale from a forgotten myth; it’s the raw, pulsating reality of December 8, 395 AD, when the Battle of Canhe Slope unfolded like a thunderclap across the frozen plains of northern China. On that fateful morning, a smaller, seemingly outmatched force ambushed a colossal invading army, shattering one dynasty’s dreams and birthing the seeds of another. It’s a story of hubris met with ingenuity, of omens ignored and opportunities seized, all played out amid the chaotic symphony of the Sixteen Kingdoms period—a time when China was a mosaic of warring states, each vying for supremacy in a land scarred by invasion and rebirth.

Why does this distant clash matter today? Because in its echoes, we find blueprints for personal victory: the art of feigning vulnerability to lure overconfidence, the power of misinformation to sow doubt, and the audacity to charge when the stars (or in this case, the ice) align. But before we charge into those modern applications, let’s immerse ourselves in the labyrinthine history of this pivotal day. We’ll wander through the tangled lineages of Xianbei chieftains, the rise and fall of ephemeral empires, and the gritty details of a battle that reshaped northern China’s map for centuries. Buckle up—this is history not as dry dates and dusty tomes, but as a high-stakes drama where every decision drips with consequence, and where even the weather plays the role of a sly antagonist.

## The Fractured Dragon: Setting the Stage in the Sixteen Kingdoms

To grasp the Battle of Canhe Slope, we must first step back into the whirlwind of the Sixteen Kingdoms era (304–439 AD), a period often called China’s “Warring States 2.0” but with higher body counts and more ethnic flair. After the fall of the Western Jin dynasty in 316 AD—thanks to the devastating Uprising of the Five Barbarians, where non-Han ethnic groups like the Xiongnu, Jie, Xianbei, Qiang, and Di rebelled against Han Chinese rule—the northern plains dissolved into a patchwork of short-lived kingdoms. These weren’t tidy nation-states; they were raw power grabs by tribal confederations and opportunistic warlords, each claiming legitimacy through bloodlines, conquests, or sheer bravado. Southern China, meanwhile, saw the Eastern Jin dynasty clinging to survival, but our story unfolds in the north, where the Xianbei—a proto-Mongolic nomadic people known for their horsemanship and shamanistic rituals—emerged as unlikely architects of empire.

Enter the Murong clan, Xianbei royalty with a knack for empire-building that would make modern CEOs envious. In the mid-4th century, the Murongs ruled the Former Yan kingdom (337–370 AD), a sprawling entity centered in what is now Hebei and Liaoning provinces. Under Emperor Murong Jun and his son Murong Wei, Former Yan controlled key trade routes along the Yellow River, blending Han Chinese bureaucracy with Xianbei cavalry tactics. Their capital at Longcheng (near modern Chaoyang) buzzed with silks from the south, furs from the steppes, and the constant clatter of iron forges producing those iconic ring-pommel dao swords—curved blades perfect for slashing from horseback.

But hubris, that eternal empire-killer, struck. In 370 AD, Fu Jian, the brilliant (if overambitious) emperor of Former Qin—a Di ethnic state that had unified much of the north—turned his gaze eastward. Fu Jian’s army, a multicultural juggernaut of 800,000 (or so the exaggerated annals claim), crushed Former Yan at the Battle of Liantai. Murong Wei was captured and executed, and the Murong heartlands became a Qin province. Yet, from the ashes rose Murong Chui, uncle to the slain emperor and a man whose very name evoked the thunder of charging hooves. Exiled to the south during the purge, Chui bided his time, serving the Eastern Jin while nursing grudges. He wasn’t just a warrior; he was a strategist, poet, and administrator who once lectured Fu Jian on the perils of overextension—advice the Qin emperor ignored at his peril.

Meanwhile, across the steppes to the north, another Xianbei lineage stirred: the Tuoba clan, rulers of the Dai kingdom (315–376 AD). Dai was a loose confederation of tribes, more herding collective than centralized state, with its heart in the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River. Tuoba Shiyiqian, the last Dai king, forged marital ties with the Murongs, wedding two Former Yan princesses in 344 and 362 AD—alliances sealed with gifts of horses and vows of mutual aid. But Dai’s fate mirrored Yan’s: in 376 AD, Fu Jian’s insatiable appetite swallowed it whole. Shiyiqian’s grandson, Tuoba Gui, escaped the slaughter, hiding in the grasslands like a wolf pup amid hounds. Gui was no mere survivor; raised on tales of Dai glory, he embodied the nomadic ethos—adaptable, resilient, and ever watchful for weakness in foes.

Fu Jian’s empire, vast as it was, proved brittle. In 383 AD, at the Battle of Fei River, his massive horde clashed with a much smaller Eastern Jin force led by Xie An. What should have been a Qin rout turned into catastrophe when Fu’s troops, demoralized by a Jin feint and river-crossing blunders, collapsed in panic. Over 100,000 Qin soldiers drowned or died in the melee, and Fu Jian himself fled, blinded in one eye by an arrow. The fallout was seismic: Former Qin splintered into the “Sixteen Kingdoms” proper, with warlords carving fiefdoms from the debris. This power vacuum was Murong Chui’s cue. Rallying exiled Yan loyalists and defecting Qin generals, Chui proclaimed the Later Yan dynasty in 384 AD, reclaiming Zhongshan (modern Baoding) as capital. His rule was a masterclass in fusion: Han-style exams for officials, Xianbei archery drills for troops, and a court where Confucian scholars debated alongside shaman priests.

Tuoba Gui, too, seized the moment. In 386 AD, he declared the Northern Wei dynasty, reviving Dai’s banner from Shengle (near modern Hohhot). But Wei started small—a cluster of yurts and 10,000 herdsmen—compared to Yan’s 300,000-square-kilometer expanse. Gui’s early years were a scramble: quelling Dugu tribe revolts, forging iron alliances with the Rouran nomads to the north, and, crucially, renewing vassalage to Later Yan. Murong Chui, ever the paternal overlord, dispatched his son Murong Lin with 5,000 cavalry in 386 to smash the rebels, cementing a lord-vassal bond. Joint campaigns followed: in 387, Yan and Wei crushed the Helan tribe; in 390 and 391, they subdued the Hetulin and Hexi, sharing spoils of grain, slaves, and steppe ponies.

Yet beneath the camaraderie lurked fissures. Tuoba Gui, sharp as a falcon’s talon, dispatched spies like his cousin Tuoba Yi in 388 to probe Yan’s underbelly. Yi’s report was damning: Murong Chui, pushing 70, was frail; crown prince Murong Bao, a bookish tactician more at home with scrolls than sabers, lacked fire; and Murong De, Chui’s ambitious brother, eyed the throne like a hawk a hare. “Internal strife will devour them post-Chui,” Yi whispered. Gui nodded, plotting in the shadows of his felt tents.

The breaking point came in 391 AD. Gui sent his brother Tuoba Gu with tribute—silks, jade, and 1,000 horses—to Yan’s court. But Murong Chui, suspicious of Wei’s growing independence, detained Gu and demanded finer steeds as ransom. Gui refused, snapping the vassal chain. He pivoted to alliance with Western Yan, a Murong splinter state led by the scheming Murong Yong, bitter rival to Chui for Former Yan’s legacy. Raids ensued: Wei horsemen harried Yan’s northern borders, rustling cattle and burning granaries. In 394 AD, as Chui’s armies besieged Western Yan’s capital at Chang’an, Gui dispatched a relief column under Tuoba Qian and general Yu Yue. It arrived a whisper too late—Yong was captured, his state extinguished—but the gesture irked Chui. “The pup bares teeth,” the old emperor fumed.

## The Prelude: A Punitive March into Peril

By 395 AD, Tuoba Gui’s provocations had escalated. Wei raiders pillaged Yan’s tribal vassals, from the Gaoche to the Tiele, swelling Gui’s coffers with loot and his ranks with defectors. Murong Chui, his health waning but pride unbowed, convened his war council in Zhongshan’s lacquered halls. Advisor Gao Hu, a grizzled veteran with scars from Fei River, urged caution: “Wei is a steppe viper—strike not in winter, lest frost claim our blades.” Chui dismissed him with a wave. “Vassals must kneel, or all crumble.” He appointed Murong Bao commander of the punitive expedition, with 80,000 infantry and cavalry— a rainbow force of Yan regulars, conscripted Han farmers, and allied Qiang archers. Flanking them: 18,000 under Murong De and nephew Murong Shao, bringing the total to 98,000, a host that darkened the horizon like a locust swarm.

Tuoba Gui, in Shengle, received word via falcon-swift scouts. Numbers daunted, but opportunity gleamed. Advisor Zhang Gun, a Han defector with a philosopher’s beard and a spy’s eyes, counseled guile: “Display weakness, sire. Let Bao’s arrogance be his noose.” Gui agreed. He ordered herds driven west into the Ordos Desert, feigning panic. His capital emptied, scouts reported to Bao’s vanguard: “Wei flees like hares before hounds.” Emboldened, Yan’s army surged north, crossing the Yellow River via ferries at Wuyuan (near modern Baotou). They accepted surrenders from 30,000 Wei vassal households—tribesmen weary of Gui’s taxes—erecting Fort Hei as a forward bastion. Engineers lashed boats for deeper fords, while campfires dotted the plains, roasting mutton under starlit skies.

But Gui played a deeper game. He dispatched envoy Xu Qian to Later Qin’s court in Chang’an, begging aid from Emperor Yao Xing. Yao, a pragmatic Di ruler consolidating post-Qin gains, sent general Yang Fosong with 10,000 spearmen—but autumn rains delayed them. Stalemate gripped the Yellow River: Yan on the eastern bank, Wei on the western, arrows whistling across the churning waters. Then, Gui’s masterstroke: captured Yan couriers, force-fed false news of Murong Chui’s death from a “sudden palsy.” Released, they galloped south, sowing dread. In Bao’s tent, whispers spread like smoke: “The lion is slain; cubs scatter.” Morale frayed; desertions trickled.

Winter’s grip tightened. November’s gales howled, frosting beards and numbing bowstrings. Sorcerer Jin An, a gaunt figure draped in fox pelts, divined doom from sheep entrails: “Retreat, my prince, or rivers run red with Yan blood.” Bao scoffed, “Omens are for peasants.” Yet doubt gnawed. On November 23, he ordered withdrawal, torching boats to deny pursuit. The river, dotted with ice floes but unfrozen, seemed a moat. Murong De protested: “Father lives; stand firm!” But Bao prevailed. The host trudged south, wagons groaning under looted grain, rearguard under Murong Lin—30,000 hardened lancers—trailing like a serpent’s tail.

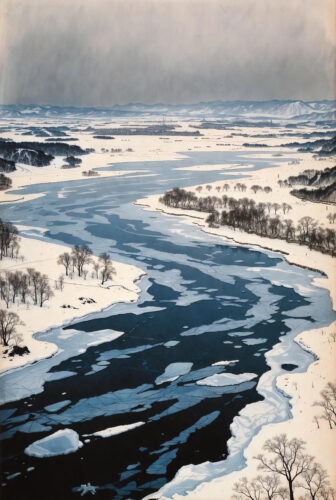

Fate, that capricious scribe, intervened. A ferocious storm on December 1 locked the Yellow River in ice—a rare, brittle bridge spanning 500 meters. Tuoba Gui, ever vigilant, mobilized 20,000–30,000 elite cavalry: Tuoba clansmen on shaggy steppe ponies, armed with composite bows and iron stirrups for unyielding charges. He led personally, cousin Tuoba Zun blocking the flanks, general Kepin Jian (his brother-in-law, a bear of a man) commanding the van. They crossed silently under moonless skies, hooves muffled by snow. By dusk December 7, Wei riders crested hills west of Canhe Slope (in modern Liangcheng County, Inner Mongolia)—a shallow basin flanked by ravines, once a herders’ trail, now a trap unwitting.

Later Yan’s vanguard, oblivious, camped in the slope’s lee. Fires crackled, soldiers diced bones for sport, while officers quaffed rice wine against the chill. Monk Zhitanmeng, a peripatetic Buddhist from the western oases, wandered the pickets, his saffron robes a ghost in the gloom. “Enemies circle like vultures,” he warned Bao’s aides. Laughter met him: “Go pray for warmer cloaks, holy one.” Murong Lin, rearward, ignored scouts’ murmurs, ordering hunts for venison. Exhaustion and overconfidence blanketed the camp like fog.

## Dawn’s Fury: The Clash That Shattered Yan

Sunrise on December 8 broke cold and clear, painting the slope in blood-red hues. Tuoba Gui’s host, concealed on encircling heights, loosed the storm. Horns blared—a guttural Xianbei wail—and 20,000 hooves thundered down like avalanches. Arrows arced in black clouds, felling sentries before alarms rose. Panic erupted in Yan’s ranks: infantry trampled tents, cavalry horses reared in chaos. Thousands perished in the crush, bodies piling like cordwood; others bolted for a nearby stream, only to drown in its icy torrent as banks crumbled under weight.

Murong Bao, roused in his command yurt, mounted amid screams. “Form lines! Shields to the fore!” But cohesion evaporated. The van crumpled under Kepin Jian’s wedge, lances skewering officers like kebabs. Tuoba Zun’s flank sealed escape, his riders herding fugitives into kill-zones. Murong Lin, half a mile back, wheeled to aid but found paths clogged by his own hunters’ wagons. He charged valiantly, sabers flashing, but Wei archers—masters of the Part